The Rationality of Inaccurate Science: Britain, Cholera, and the Pursuit of Progress in 1883

By Emma Grunberg, University of Washington, Seattle

In

1883, just before the

European scramble for African territory and resources reached its

height, France and Germany were engaged in another competition on the

streets of Alexandria, Egypt. As an epidemic of cholera waned

there, the French and German governments both sponsored scientists to

try to discover the organism that causes the disease, a search

conducted among the corpses and sewage of Alexandria. Louis Pasteur

handpicked the French team; Germany’s Robert Koch, discoverer of the

tuberculosis bacterium, led his own. France, a major colonial power,

and Germany, a newly unified country, wanted not only to find the

organism responsible for so much human suffering: they also competed

for the prestige that would come with the discovery, prestige that

would reinforce their right, as modern, progressive, and scientific

nations, to colonize Africa and reap the spoils of their empires.

Great

Britain was curiously

absent from the race to identify and hopefully cure cholera. Though

Britain’s John Snow discovered in 1854 that cholera was waterborne,

Britain put its economic interests first during the epidemic. To avoid

the economic consequences that quarantine would have on trade through

the Suez Canal, Britain promoted theories of disease that many of its

own scientists admitted were outdated. One French newspaper said of

British conduct during the epidemic:

It is England that maintains the closest relations with Egypt; thus the most pressing duty of the British Government is to use the most effective means to stop the plague. But the brutality that characterizes [Prime Minister William] Gladstone’s policy in general is manifested again on this occasion, and, in the interest of English trade, the most basic international agreements are disregarded. [1]

Britain

did scorn

international quarantine agreements. However, a closer look at the

reports and correspondence produced during the epidemic reveals that

British officials, far from disregarding international opinion, were in

fact preoccupied with proving the scientific credibility of their

policies amidst the prevailing international climate of scientific

rivalry.

Some

scholars have examined

the European focus on science and hygiene during the ‘New Imperial’

period, as well as Britain’s use of science as a instrument to support

colonial policies. Yet current scholarship cannot explain

Britain’s complex, concerted, and often-contradictory effort during

the 1883 epidemic in Egypt. I argue here that Britain’s

reaction to the epidemic of 1883 demonstrate how the late nineteenth

century rivalry for prestige and progress had permeated British

policies, which were framed in the language of objectivity, rationality

and modernity. Though Britain did not materially participate

in the race to find the cholera bacterium, the 1883 epidemic

nonetheless provided a field for Britain to participate in the

otherwise Continental rivalry for scientific and cultural hegemony

during the late nineteenth century.

Since

Rosenberg’s study of

three American epidemics that took place in three different decades,

historians have viewed epidemic as a means of interpreting the

priorities of a society, nation, and state.[2]

Rosenberg asks how epidemics

were understood,

what causes were ascribed to them, which

institutions responded to them (the government? the church?), and what

those responses were. I focus on the examination of the

process of self-justification as a means of better under-standing

colonial priorities. My concern is how and why the British

defended their policies scientifically, and what this reveals about

Britain’s priorities with respect to their international

image. A crisis as significant as the epidemic I consider

reveals Britain’s own preoccupations, particularly evident in the

British discourse during the height of the epidemic in the Summer of

1883.

I

first review the

literature that addresses the cultural implications of the New

Imperialism as they relate to the pursuit of “progress and

modernity.” I then discuss how science became a vital part

of this pursuit, as it became more prominent and professionalized, with

the advent of Darwinism and other developments. Next, I examine the

state of European science with regard to epidemic disease,

providing a background for understanding the controversies surrounding

disease theory and policies, and explaining why quarantine, cholera and

the Suez Canal were all such significant issues for Europeans during

the late nineteenth century. I also discuss the work of

scholars who have tried to explain why different countries adopted

different disease theories and policies, and how my analysis adds to

their work.

In

studying the negative

effects of British imperial health policies, scholars have asked: to

what extent can the use of misguided science or policies be considered

purposeful or exploitative? During the 1883 epidemic,

Britain’s focus on sanitation policies, which was tradition that had a

strong domestic basis grounded in Britain’s sense of their own hygienic

superiority. Finally, I provide the economic and political

context for Britain’s newly established presence in Egypt in

1883.

I

ultimately conclude that

the European rivalries of the New Imperial period – economic, imperial,

cultural and scientific – spurred the British desire to protect their

economic interests while trying to present their policy

during the

epidemic as the most scientifically modern and progressive in Europe.

Modernity and

the New Imperialism

From

the 1870s to the start

of World War I, European powers engaged in what historians have termed

the ‘New Imperialism’ a period of intense nationalism at home and

colonial competition abroad. The Berlineise Conference

(1884-85) established the ground rules for the ‘scramble for Africa’:

the process by which Europe gained control of the entire

African

continent with the exception of Ethiopia and Liberia. During

this period, the players in the imperial game expanded beyond Britain

and France to include other European nations, Russia, the United

States, and Japan. The main focus of colonialism also shifted

to territorial expansion.[3]

Competition

between states

raged in the colonies in ways that it could not at home: Belgium

acquired a vast rubber forest in the Congo, Chancellor Bismarck of

Germany decided that his country’s position in the world needed a boost

that only colonial expansion could provide, and France shrugged off the

humiliation of its recent loss in the Franco-Prussian War and restored

its role at the center of the European balance of power.

Britain,

therefore, was no

longer the world’s sole industrial power, nor an unchallenged imperial

power. Victorian classicist J.R. Seeley famously wrote that

the British Empire was acquired “in a fit of absence of

mind” – in other words, through exploration and trade

conducted by people who lacked the purposeful intent to rule vast

territories. Historians agree that during the New Imperial period,

Britain’s relationship to its empire changed and became more

recognized, institutionalized, and publicly visible in response to

growing competition from abroad. According to the

Historical

dictionary of the British empire, “Throughout much of the

nineteenth century, the British viewed Africa as their private

preserve…By the end of the century, however, that complacency was

over…the British became increasingly worried about maintaining their

paramountcy.”[4]

In the 1880s, driven by anxiety over the future of the empire, a British pressure group known as the “Constructive Imperialists” advocated for pro-imperial causes, such as greater trading privileges for colonies, going against the laissez-faire policies prominent during most of the nineteenth century. Often associated with politician Joseph Chamberlain, the movement was “in part a response to changes in the international environment,” where now Britain was duly challenged by “the growing industrial and military strength and increasing overseas activity of, in particular, Germany, France, the United States, and Russia.”[5]

Through

colonial expansion,

Britain tried to preserve its global dominance and maintain control

over its international financial interests. Some historians

date the beginning of the New Imperial period to two events that

preceded (and prompted) the Berlineise Conference: the acquisition of

the Congo Free State by King Leopold in 1882, and Britain’s occupation

of Egypt and the Suez Canal in that same year.[6] The latter

was an

attempt to restore Egypt’s financial situation and protect Britain’s

interests through outright occupation. Those two acquisitions

were arguably the first major moves in the European scramble for

African territory and resources.

The

European rivalries

surrounding the scramble operated on multiple levels, not just in the

realms of territorial and economic expansion. There was also

a less tangible competition for national prestige and the mantle of

‘civilization’. The remarkable success of imperialism during this

period existed alongside European anxieties over preserving both their

perceived racial and social superiority to the peoples they colonized,

and their position with respect to other European powers.

European modernity,

as exemplified by the superiority of European science, European

lifestyles, and the intrinsic superiority of the Caucasoid race, was at

the heart of the colonial civilizing mission.

Fueling

this rivalry was the

growing acceptance of Darwinism and its counterpart, social Darwinism,

by many Europeans. Europe’s self-conscious concern with

establishing it position atop the evolutionary heap is evident in the

global exhibitions hosted by Britain throughout the nineteenth century.

The Native village’ display, a staple of the exhibitionary order,

defontmonstrated the so-called backwardness of non-Western life and

were

“used to illustrate concepts of social evolution…which derived

authority from their air of scientific objectivity but essentially

reflected Europeans’ views of them- selves.” [7] However illogical

scientific racism might seem today, during the late nineteenth century,

social Darwinism’s status as a legitimate theory helped justify

Europe’s subjugation of non-white peoples.

McClintock

argues that the

new ideas about evolution placed imperial violence in the context of

the natural evolutionary struggle, making “nature the alibi of

political violence and [placing] in the hands of ‘rational science’ the

authority to sanction and legitimize social change.”[8]

Similarly,

Mazlish writes that “Race is a product of ‘modernity’ and a partial

response to it… Racial distinctions could replace the faltering

aristocratic ones as a justification for hierarchy.”[9]

‘Scientific

objectivity’, as applied to evolution, race and many other fields,

emerged as a

benchmark of modernity and an important justification of

imperialism during this period, one that motivated the British during

the 1883 Egyptian cholera epidemic.

Science, Civilization and Imperialism

The rapid industrialization of Germany and the United States, swept Britain up in what contemporaries saw as a race among nations, in which the “survival of the fittest” was to be measured by success in achieving “national efficiency.” In this, the methods of science were the essential instruments. The rhetorical translation of science and its creeds, from the threatening language of materialism and socialism, to the instrumental language of management had begun. [10]

During

the New Imperial

period, science became a vital part of claims to modernity: as a tool

for “proving” racial superiority, and as a way of demonstrating the

advancement of a culture and contributing to national

prestige. From the 1870s to the 1880s, science itself reached

the peak of its prestige as an alternative religion, a “Creed of the

Future.”[11]

MacLeod argues

that this triumphalism

was short-lived, as “scientific policies” were soon attacked.

In 1893, T.H. Huxley, a biologist and friend of Charles Darwin, gave a

lecture in which he “mooted the possibility that evolution… could not,

in itself, produce what High Victorians could confidently call material

‘progress.’”[12]

While the cholera

epidemic of 1883 was

situated within the highpoint of European political confidence in

science, the growing specialization of science at the time of the

epidemic made it less intelligible to politicians and officials, and,

ironically, more important for justifying and informing

policy.

In

her analysis of

international sanitary conferences on cholera from 1851 to the turn of

the century, historian Valeska Huber tracks the growing professionalism

of science and its increasing importance to the political

delegates. Her summary of the 1851 conference sounds odd to

modern ears: “Scientific discussions were to be avoided…the diplomats…

criticized the scientists as long-winded and impracticable.”[13]

At the time,

medical debates, especially regarding epidemic disease, relied on

deductive philosophy as well as empirical observation, operating on a

plane of knowledge familiar to the political

delegates.

Contrast

this with the 1885

conference, the first after Koch’s discovery of the cholera bacterium,

when bacteriology had become “associated with coherence, exactitude and

modernity”[14]

and:

Medical knowledge became specialist knowledge which was complicated and not accessible to the diplomats…While this self-fashioning of the modern scientist meant on the one hand that diplomacy and science belonged now to completely different spheres, at the same time science became relevant to politics to a formerly unknown extent. In the fight against cholera politicians had to rely on scientific expertise and prescriptions.[15]

As

science became more

rigorous and, therefore, more difficult for nonprofessionals to

understand, its prestige grew and its theories became more important

for policy formulation, especially regarding epidemic

disease. This was equally true in the colonies

– at least on the rhetorical level.

Science,

including medicine,

played a particularly important role in the colonies as part of the

justification for European rule. “Well into the twentieth

century,” notes the Oxford

history, the physical and life sciences “retained a

fundamental belief in scientific and technical progress rooted in

Imperial ideas of the beneficient spread of Western science.”[16]

But no matter how

patriotic scientists might have been, British imperial officials did

not always give them cause for cheer. Worboys, Arnold, Watts,

and others have discussed how science and medicine were used as tools

in the imperial struggle. Arnold, in relation to the British imperial

presence in India, argues that “Science was…part of the self-identity

of the European elite and its self-declared mission to ‘improve,’ to

‘civilize,’ ultimately to ‘modernize,’ India.”[17]

Lord Curzon, Viceroy of India from 1899 to 1905, realized the growing importance of science in Europe. History does not confirm that Curzon was a great benefactor of scientific research in India. David Arnold points out that in the 1880s, Sir Ronald Ross, winner of the Nobel Prize in Medicine, wrote that under the Anglo-Indian government “the great bacteriological discoveries of Pasteur and Koch ‘were scarcely recognized, or were ridiculed.”[18] Ross “felt that he was consistently obstructed by the government and the [Indian Medical Service] chiefs in his own search for the malaria parasite in the early 1890s.”[19]

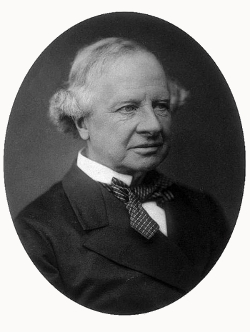

Lord

George Nathaniel

Curzon, Viceroy of India, 1898-1905.

Image

Source: Wikipedia

Commons

Ross

was by no means an

anti-imperialist; believed that the British were “superior to subject

peoples in natural ability, integrity and science…They [had] introduced

honesty, law, justice, order, roads, posts, railways, irrigation,

hospitals…and what was necessary for civilization, a final superior

authority.”[20]

Still, he and

other scientists worried

that the government in India was hindering British research.

Ernest Hart, editor of the British Medical Journal,

said in 1894 that the Anglo-Indian authorities regarded research as an

administrative “nuisance,” and that they followed a course of

“respectable conservatism” rather than pursuing “potentially

controversial research.”[21]

But as Arnold

notes, the virtues of medical science were extolled even as research

and basic care were not adequately supported. Arnold’s

discussion of Curzon’s rhetoric is worth quoting at length:

Curzon was more alive than many of his bureaucrats to the scientific spirit of the age and to the practical, as well as polemical, needs of high imperialism…Science (and not just the grand public works that had dominated nineteenth-century thinking) could be a force for far-reaching change, an aid to more efficient government, and not least, in an age of increasingly assertive nationalism, a fresh source of legitimation for British rule…there might be those who questioned the value of Britain’s laws and religion, but about science, especially medical science, he said, there could be no doubt. Medicine alone was the justification for British rule. It was “built on the bed-rock of pure irrefutable science”…Medicine lifted the veil of purdah “without irreverence”; it broke down the barriers of caste “without sacrilege.” Medical science was “the most cosmopolitan of all science” because it embraced “in its merciful appeal every suffering human being in the world.” [22]

In

Curzon’s formulation,

medicine is an unarguable justification because it is based on fact and

reason, it can lift away irrational and backward traditions like caste

and purdah,

and it is universal, thus

requiring a competent global power to support and provide it.[23]

It was therefore an excellent justification for modern,

forward-thinking imperialism.

As

in Egypt during the 1883

epidemic, even as British officials resisted the growing scientific

consensus on the germ theory of disease, their rhetoric on science

became loftier. Arnold acknowledges this seeming

contradiction but, like other scholars, does not fully explore

it. He does discuss another irony, that Indian scientists

were often actively discouraged from joining the medical service.

“Despite the mounting pressure for Indianization,” Arnold wrote, “these

remained essentially European services and their racial exclusiveness

helped…shape a shared scientific culture and a common ideal of

scientific service to the empire as a patriotic and paternalistic duty.”[24]

Clearly, these

were anxious times for British imperialists who felt they had something

to prove. The spirit of the age does not speak to a sense of

security, but to a constant worry about maintaining cultural and racial

superiority in the face of European rivalry and colonial

rebellion.

There

was a corresponding

worry about maintaining national prestige that was sometimes used

against British imperial officials by scientists and others who worried

about the decline of Britain’s scientific reputation compared to

Continental Europe – and beyond. Arnold

writes that Edward Hart, editor of the British

Medical Journal,wondered:

why it was that all the major discoveries in tropical pathology had been made by foreigners – French, German, even Japanese – not by Britons. In an age of imperial rivalry, it was galling to have to recognize the pioneering work on cholera, malaria…plague had been done by others.[25]

Accustomed

to being on the

cutting edge of all aspects of inquiry, the prospect that Britain would

be eclipsed not only by France and Germany, but by the non-European

Japanese was an uncomfortable thought. “It is not right,”

Hart said, “that we should essay to govern millions and withhold from

them the full measure of civilization. Nor is it seemly that

we in England should have to go for so many years to France and Germany

for textbooks in a subject [tropical medicine] in which England should

lead the way.”[26]

After all,

Britain ruled more tropical locales than any other European country and

had therefore the most direct access to resources for research.

Similarly, a Dr. A.C. Crombie complained that the British:

have allowed a Frenchman to find for us the amoeba of our malarial fevers, and a German the…bacillus of cholera which is surely our own disease, shall we wait till someone comes to discover for us the secrets of the continued fevers which are our daily study, or shall we be up and doing it for ourselves? [27]

As

Harrison notes,

“Controversies over priority for ‘discoveries’ in the emergent

discipline of tropical medicine had distinctly nationalistic overtones.”[28]

We see that the

same anxieties preoccupied colonial officials and British scientists,

but while scientists wanted actual action, officials were largely

concerned with image. In 1883, this separation of rhetoric

and reality is evident in the British handling of an epidemic of

cholera, an event that attracted the attention and concern of

governments across Europe. Why would cholera in Egypt be so

troubling?

European

Responses to Epidemic Disease

Epidemic

disease was one of

the most important threats to nineteenth- century societies,

governments

and scientists. The two most prominent theories of epidemic disease

during the nineteenth century were “contagion,” which came to encompass

germ theory, and “miasma,” which generally lent itself to an approach

to disease control known as “sanitationism.” Germ theory has been

proven correct, and we now know that diseases like cholera are passed

indirectly from person to person via tiny organisms. Prior to

the major bacteriological advances of the late nineteenth century,

however, multiple types of “contagion theories” circulated, and

quarantine was often an ineffective method of disease prevention

because without knowledge of how various diseases were transmitted, it

was difficult to come up with a plan that could prevent

infection. Some contagionists, including Koch himself, were

skeptical of quarantine, and most Europeans agreed that good hygiene

was vital for health.[29]

The

miasma/contagion debate, therefore, was far from

clear-cut.

Miasma

theory held that “bad

air” accumulates in certain places, provoking

illness. These diseased clouds were said to arise from

“decayed organic matter or miasmata…Believers

in the miasma theory stressed eradication of disease through the

preventive approach of cleansing and scouring, rather than through the

purer scientific approach of micro- biology.”[30] Microbiologists

believed that the tiny organisms that formed the subject of their field

passed from person to person, sometimes through other carriers like

insects or feces. Proponents of this theory were known as

contagionists, and Robert Koch’s discovery of the tuberculosis

bacterium in 1876 lent them credence. Another frequently used

term in 1883 was ‘importation’, the theory that cholera was brought to

a place via a certain carrier, and clearly an idea built on the concept

of contagion. The British countered with local-origin theory,

less dependent on the miasma theory, but influenced by the concept of

localized miasmas.

For many contagionists, quarantine was a necessary response to infectious disease, as it isolates infected individuals to prevent the disease from spreading and can provide a sense of control over the situation. ‘Sanitary cordons’, barriers erected around a town that was suffering from a disease, were another option. The Egyptian health authorities used cordons during the 1883 cholera epidemic, earning scorn and disgust from British officials and journalists.

The British had long been suspicious of quarantine, and not just because they were inconsistent and often ineffective. As the country that relied most on sea trade, quarantines were a nuisance for Britain. In 1882, the Bombay Gazette expressed the Anglo-Indian frustration at the imposition of new international quarantine regulations:

A steamer in quarantine is not only forbidden to allow a passenger to set foot on shore but cannot even take the canal pilot on board…These vexatious restrictions are so oppressive that companies running steamers regularly have had to send out stem pilot-boats to Suez…and in many cases trading steamers were held back to the detriment of commerce and to the positive loss of owners and shippers. [31]

For

decades, pro-imperial

Britons had linked the success of British commerce with the spread of

civilization and Christianity. International trade was not

only economically vital for Britain, it was also upheld as one of the

pillars of the capitalist, civilized lifestyle that Britain could offer

the world. Britons argued that quarantine restricted trade

and nurtured panic and other uncivilized behavior.

In March 1882, one month after new quarantine regulations were established for the Suez Canal, a British politician wrote:

Her Majesty’s Government are not prepared to acquiesce in the recurrence of such arbitrary and capricious acts of the International Board as have of late caused enormous losses to shipping; and they can no longer assent that an irresponsible body should have the power of making unreasonable laws which disturb the whole Eastern trade of Great Britain and unduly impede her communications with India. [32]

The

author was Granville

George Leveson-Gower (2nd Earl

Granville), Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, who would monitor

the British response to the 1883 Egyptian epidemic, and he was writing

to Sir Edward Malet, Agent and Consul-General, who would manage the

situation on the ground in Egypt. For both Granville and

Malet, harsh quarantines were to be avoided as much as possible. So

too, the theory of importation must be resisted, as it implied that

quarantine would be the only effective option for controlling cholera.

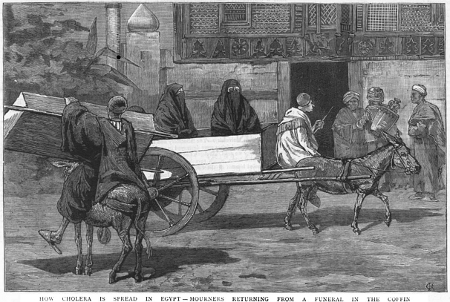

The other side was equally determined that harsher regulations would come out of the epidemic. The cholera epidemic in Egypt brought panic in Mediterranean Europe. The disease itself preoccupied Europeans; it was the subject of all but two of the “international sanitary conferences” held from the 1850s onward. Cholera prompted drastic responses because of its seemingly random ravages. It held a unique fascination and terror for nineteenth-century Europeans. To understand the panic underlying European attitudes towards the 1883 epidemic, and the arrogance Britain displayed in trumpeting its own freedom from cholera for several years, it is important to realize the hold cholera had on people’s imaginations.

Granville

George

Leveson-Gower (Second Earl Granville),

Secretary

of State for Foreign Affairs, 1880-1885.

Image

Source: Wikipedia Commons

Several scholars have singled out cholera as especially troublesome to Victorian romantic ideals and social norms of privacy. “It was not easy for survivors to forget a cholera epidemic,” writes medical historian Charles Rosenberg. “The symptoms of cholera are spectacular; they could not be ignored or romanticized as were the physical manifestations of malaria and tuberculosis.”[33] He quotes an Albany man, who wrote in 1832: “To see individuals well in the morning & buried before night, retiring apparently well & dead in the morning is something which is appalling to the boldest heart.”[34] Cholera‟s rapid onset increased people's perception of the need for far-reaching public health reforms.

Tuberculosis, yellow fever and other pestilences claimed more lives in the West, but at least they could be incorporated into the culture, into acceptable ways of being ill and dying. The literature of the era contains many examples of the quiet, romantic death: several of Charles Dickens’s characters, for instance, as well as Beth in Little women. Cholera never found a place in this understanding of epidemic disease. Its symptoms were “deeply disgusting in an age that…sought to conceal bodily functions from itself,”[35] writes historian Richard Evans. Death could occur within hours and usually came within days, as the victim defecates his bodily fluids and then a type of ‘rice water’, and the skin becomes dark and the eyes sunken. The pain is unbearable. Evans evokes this fear:

The thought that one might oneself suddenly be seized with an uncontrollable, massive attack of diarrhea on a train, in a restaurant, or on the street, in the presence of scores of respectable people, must have been almost as terrifying as the thought of death itself. [36]

This

‘Asiatic’ disease,

which originated in India, was a truly ‘uncivilized’ disease,

associated with the East and with lower-class districts where sewage

was badly managed if it was managed at all.

The

fact that this cholera

epidemic occurred in Egypt was equally important in capturing European

attention, given the symbolic and practical value of the Suez Canal as

a gate between Europe and the diseases of the Orient. At a

sanitary conference in 1885, a French delegate stated that the,

“English argument ‘Everyone is master in his own home’ would be

irrefutable if the ships did not pass through the Canal which is a

common gate to England and to the other European nations.”[37] Although

the British controlled Egypt, the French, as the above passage

indicates, did not feel that this gave them special privileges to

determine policy for what, in their view, was an international issue

that would affect all of Europe. The Canal, according to

Valeska Huber, was “a single, controllable gate between India and

Europe,”[38] one

“which was open for commercial enterprises but closed for microbes.”[39] Policing Europe’s

land borders was nearly impossible; this European-controlled portal had

to be, in the opinion of Continental Europe’s delegates to the sanitary

conference, rigorously protected.

During the sanitary conferences, there was a constant tension between the interests of each country – particularly Britain’s economic interests – and the new norms of international relations, which Huber characterizes as, “the intricate relationship between nationalism and internationalism.”[40] It was difficult for delegates to agree on an international policy when the major powers were informed by their own experiences. Harrison writes that:

All the medical arguments advanced at international sanitary conferences were, in some degree, articulations of each country’s experience of epidemic disease. France seemed to be afflicted with cholera first in her Mediterranean ports, seemingly as a result of commercial exchange with the middle east. This gave rise to the understandable belief that cholera was a disease transmitted by human contact. British epidemiologists were convinced, however, that no single case of cholera had ever reached a British port direct from India, and that the great cholera pandemics had spread overland from Asia to Europe.[41]

France,

therefore, was also

acting on its own interests, which concerned keeping cholera out of

France, while Britain was less concerned about importation because it

had not experienced severe epidemic cholera since 1866.

According to Harrison, medical policy was largely determined by this

experience with disease. Similarly, historian Peter Baldwin

argues that it was a country’s “geographic placement in the

epidemiological trajectory of contagion, that helped shape their

responses and their basic assumptions about the respective claims of

the sick and of society.”[42]

For Evans,

political ideology also influenced the tendency of certain cities and

countries to embrace certain theories of disease.

I

argue that economic

interests, practical concerns about importation, and cultural and

ideological influences are not enough to explain Britain’s complex

reaction to the 1883 epidemic. In this time of crisis, the

British responded according to the new expectations of the

times. The historical context of the epidemic determined the

rhetoric the British used in responding to it. Scientific rhetoric was

not created in a vacuum, but was forged out of the intersection of

economic, scientific and colonial discourses.

Different

writers have tried

to connect miasma and contagion theories to different ideologies and

methods of government. In Death

in Hamburg,

Evans argues that the German port city’s

leadership was influenced more by British-style laissez-faire government

than by Bismarck’s centralization policies. Evans examines

Hamburg’s sixteen nineteenth-century cholera epidemics, which occurred

over the span of a few decades. Hamburg was a bourgeois port

city, and the middle class reaped the benefits of free trade and

liberal policies at a time when most German cities were becoming more

controlled by the imperial capital of Berlin. Evans

identifies the Hamburg middle class as natural supporters of the miasma

theory of disease.

The theory that some poor and unsanitary

places were prone to “bad air” was convenient for those who favored a

non- governmental approach to solving social problems.

According to Evans, miasma theory functioned almost as a tool to

justify noninterventionist public health policies. “The

solution of [health] problems was closely bound with structures of

social inequality and social conflict in the city,” he

argues.[43]

At the same time,

Bismarck’s Berlin promoted

bacteriology, and in 1883, the famous scientist Robert Koch, funded by

the German government, found the cholera bacterium in Egypt and then

confirmed his discovery in India.

Evans

examines the Hamburg

city records and concludes that inaction in the face of persistent

cholera breakouts eventually became untenable for Hamburg authorities,

and that cholera contributed to Hamburg’s loss of independence during

the late nineteenth century. Hamburg’s political subjugation,

and the loss of support for the miasma theory of disease and lack of

action in the face of cholera, fed on each other. As Evans

writes, “More died in Hamburg than just people…[cholera] marked, even

if it was not alone in bringing about, the victory of Prussianism over

liberalism, the triumph of state intervention

over laissez-faire.”[44]

Evans directly

relates the rise and fall of scientific theories with the fortunes of

their political supporters. He writes that Koch’s discovery

and Germany’s centralization and quest for greater global power fed on

each other:

At the same time as the Germans, the French, the British, and other nations were engaged in a desperate race to annex territory in the name of Civilization, they were also involved in a furious competition to conquer disease in the name of science. No wonder, then, that Koch was acclaimed as a hero on his return [from discovering the cholera bacillus]. [45]

Evans’s

analysis is helpful

in explaining British theories of disease, but examining British

rhetoric indicates that Britain was as preoccupied with the “furious

competition” as Pasteur’s France or Koch’s Germany.

Endorsement of the miasma theory, in other words, did not equal

withdrawal from the scientific rivalry.

Colonial

Medicine

Did the British handling of epidemics in their colonies represent a deliberate attempt to ignore the ravages of the disease in order to concentrate on more important economic priorities? Or was their seeming incompetence a result of genuinely subscribing to scientific theories that would later be proved inaccurate? Watts proposes in Epidemic and history a Foucauldian argument that imperialist powers tackled “disease constructs” rather than actual diseases, with the goal of “Development” (in the economic sense), rather than the eradication of disease or the improvement of public health.[46]

Worboys,

in his review of

Watts’ book, says that some social historians have a problem with the

book’s “simplification” of complex colonial motives under the buzzword

of Development, that imperialists had less real power and scientific

knowledge than Watts assumes, and that it is difficult to separate the

“objective facts” of disease from their cultural

construction. In reference to Watts’s chapter “Cholera and

Civilization,” Worboys writes that the British reluctance to accept

Koch’s discovery of the cholera bacillus was “well-grounded in the

‘facts’ and…the choices between different sanitary policies were openly

debated.”[47] After all, there

is a place for

skepticism in science, and there were questions to be asked about

Koch’s findings.

Watts, however, has amassed evidence to suggest that British responses to cholera were not always as misguided as they were in the late nineteenth century. His reading of the sources has convinced him that during the 1850s, British policies were generally in tune with the science of the day, but in the year 1868, a “great reversal” took place, wherein the British refuted germ theory and instituted policies that either ignored the problem of cholera or made it worse. Watts writes:

Concealment and amnesia were intended to support Britons’ image of themselves as humanitarians who were not driven solely by commercial self-interest, despite what foreigners might claim. Feigned unawareness (and among lower-echelon officials, very possibly actual unawareness) of changed cholera policy was also supportive of the fiction that the preservation of age-old socio-political and legal systems was a particular virtue that set the English apart from the fickle revolutionaries on the other side of the Channel. [48]

The

preservation of age-old

systems that Watts mentions refers to the British strategy of ‘indirect

rule’, using indigenous systems of authority to control territory more

efficiently. Watts argues that the British portrayed indirect

rule as a cohesive, rational policy, when in fact they were simply

uninterested in an interventionist cholera strategy. When the

principal health official in India, James McNabb Cuningham, was

revealed as a contagionist in his report on the 1867 cholera epidemic,

Watts shows how London developed an “ideology” that could counter calls

for quarantine, then attempted to discredit dissenting

voices. Watts criticizes British and “Anglophile American”

historians for not examining the 1868 policy switch more closely. He

argues that British leaders deliberately based policy on bad science to

further their own ends.

Watts is not alone in his reasoning, although he has advanced it most fully. Other scholars’ work follows his general argument. The following are selections from various scholars’ work on British India:

“The apathetic rulers intervened, even though half-heartedly, only when it affected their work…” “Supposedly wedded to a policy of laissez-faire, the British rulers did not hesitate to deviate when imperial interests so dictated.” “Thus, comprehensive public health…did not make it to the priority list of British rulers.” “British rulers, dominated by class interests of the landlords and wealthy merchants, were insensitive to the abysmal health conditions of the ordinary people.” [49]

Arnold does not focus on the question of imperial motivation, but he agrees that the British in India had an “ostrich-like” policy, preferring “for political and commercial reasons to pursue a noninterventionist, laissez-faire policy toward cholera.” This was based on the “‘Orientalist’ assumption that India was intrinsically different from Europe.”[50] Harrison also argues that Britain used outdated ideas as tools to support their preferred policies. For Harrison, “Political and professional interests impinged directly on medical theory,” as the Anglo-Indian government’s position on cholera as a localized disease was developed to support their anti-interventionist, anti-quarantinist health policies:

In India the debate over cholera was intertwined with the issues of internal and maritime quarantine, and with questions of government finance. The government came to adopt an official position on cholera which vindicated its policy of limited intervention in public health and its opposition to the quarantines imposed against India. [51]

Harrison

pursues a similar

line of argument to Watts in that he traces how the British

deliberately manipulated scientific information so as not to damage the

basis of their policies.

In order to maintain its policy of detachment from public health, the government was prepared to go to extraordinary lengths, manipulating the flow of information and theoretical discussion in official circles…the rigidity of official doctrine between 1870 and 1890…served only to diminish the government’s credibility abroad. [52]

There

seems to be a growing

scholarly agreement that while Britain’s official theories on the

causes of cholera might have been culturally influenced, in the

imperial context, scientific theory was purposefully employed to

provide a rationale for policies that would coincide with British

economic interests.

I

do not attempt here to

prove or disprove Watts’ bold argument: that British imperial disease

policy was founded upon a conscious deception. I do argue that science

was used to support economic goals. As I shall discuss, and

as Worboys states in his review of Watts’ work, the British had several

reasons to have confidence in their sanitationist approach to disease,

and their actual motivations were probably a mix of a purposeful

tailoring of

theories to support their trade interests, and of

influences from a longtime cultural tradition of British hygienic

superiority. Their approaches to disease in the domestic and

imperial contexts were somewhat consistent.

British

Perceptions of Their Own Hygienic Superiority

During the late nineteenth century, living a clean, orderly life was perceived as a sign of civilization. This idea was bound up with imperialism: Europeans, especially in Africa, made frequent references to the unsanitary habits and dwelling places of the peoples they encountered and colonized. Exporting the outward trappings of European life – living in square rather than round houses, for instance – was an attempt to export Western “civilization.” European cultural superiority was not a new idea in the late nineteenth century, but it gained new power during this period: as European countries competed for colonies, hygiene became a marker of social evolution. McClintock, in her discussion of the importance of soap for Britain in the late nineteenth century, argues that “at the beginning of the nineteenth century, soap was a scarce and humdrum item and washing a cursory activity at best. A few decades later…Victorian cleaning rituals were peddled globally as the God-given sign of Britain’s evolutionary superiority.”[53]

For

the British, good

hygiene was both a marker of superiority and the most effective way to

combat disease, on both the domestic level and the communal

level. Edwin Chadwick, Florence Nightingale and other

prominent Britons all believed that improving public sanitation was the

most important way to improve the health of a nation.[54]

Baldwin writes

that:

Sanitationism, in its all-explaining Chadwickian version, was more than just an account of disease etiology. At its broadest, it was a totalizing worldview resting on certain presuppositions concerning the balance of nature and the role of illness and disease in the divine harmony of the universe. [55]

As

the century went on, the

divine became less important, but the significance of sanitation for

Britain remained strong.

In

1885, Dr. Ballard of the

Local Government Board in Britain declared that “sanitary science [is]

the product of the English Mind.”[56] England, with its

squalid industrial cities and severe air and water pollution, certainly

cried out for change. Through legislation like the 1866

Sanitary Act, the gathering of statistics, and public projects to clean

up polluted rivers, many British officials tried to clean up their

environment. The theme of action in the face of squalor would

be often brought up during the 1883 epidemic.

Another

reason that the

British could be confident in their approach to dealing with cholera

was their comparative freedom from the disease; severe epidemic cholera

had not occurred in Britain since 1866, and although cases occurred in

1872, there were “very few deaths and no epidemic crisis.”[57]

The causes for

this are uncertain; Watts attributes British good fortune to quarantine:

It is a cause for wonderment that the English were not regularly decimated by epidemic cholera in the decades following what was in fact the last major visitation – that of 1866-67…Aside from the contingencies of change…what probably saved the English was the imposition of quite rigorous cquarantine controls between India and points west. [58]

Whatever

the cause, the

situation bred confidence. According to Hardy:

England’s limited experience of cholera between 1867 and 1892 encouraged public complacency [reflecting] the growth of confidence in the sanitary service, as well as a wider public interest in sanitary matters…[cholera’s] continued existence on the Continent was a further illustration, if need be, of superior English standards of hygiene, and generally greater degree of civilization. [59]

This

emphasis on hygiene as

a sign of progress also manifested itself in the domestic

sphere. McClintock discusses the images of imperialism and

racial superiority in soap advertising during the New Imperial period,

demonstrating how the link between hygiene and ideas of race and

progress played on British anxieties. McClintock argues that soap

connected the middle-class virtues of domesticity and cleanliness to

the insecurities and rivalries of the era: “Both the cult of

domesticity and the new imperialism found in soap an exemplary

mediating form.”[60]

Ironically,

through the excision of women’s work, soap – a feminine, domestic

symbol – came to represent “the sphere of male ‘rationality’ although

the logical link was tenuous…soap advertising…took its place at the

vanguard of Britain’s new commodity culture and its civilizing mission.”[61]

Soap linked the

middle-class virtues of cleanliness in the home with the imperial

mission to uplift foreign peoples.

The

reports and official

correspondence regarding cholera were clearly not meant for mass

consumption in the same way as a bar of soap; the debate over the

origin of cholera only ever reached a limited audience.

However, the fear of cholera and the conversation about what could be

done to control it took place in the public sphere as well as in

diplomatic and scientific circles. Advertisements offering

various “miracle cures” proliferated in newspapers during the fifth

global cholera pandemic (1881-1896), and politicians, journalists, and

lecturers assured the jittery public that the same British common sense

and cleanliness that had kept the country cholera-free for some years

would continue to protect them.

Another

perceived British

advantage was the British climate, which some thought was particularly

suited to good health, as opposed to the hot, disease-ridden tropics.

There was a difference of opinion here; some thought that the

differences in the incidence of epidemic disease in Europe and the

tropics was due to differences in hygiene, while others thought they

had more to do with the tropical climate and environment that

negatively influenced Britons as well as ‘natives’. Britons brought up

in India, as one official wrote, “did not reach ‘the same high physical

and mental standard as those…who had been born in the United Kingdom’.”[62] Although the

press referenced climate during the 1883 epidemic, officials almost

exclusively concentrated on hygiene, emphasizing the ability and need

of Britain to take proactive action

to temper the effects of the epidemic.

Through

her close reading of

soap advertisements, McClintock concludes that the many aspects of the

New Imperial rivalry cannot be explained solely by economics:

The Victorian obsession with cotton and cleanliness was not simply a mechanical reflex of economic surplus…Soap did not flourish when imperial ebullience was at its peak. It emerged commercially during an era of impending crisis and social calamity, serving to preserve, through fetish ritual, the uncertain boundaries of class, gender and race identity in a social order felt to be threatened by…economic upheaval, imperial competition and anticolonial resistance. Soap offered the promise of…a regime of domestic hygiene that could restore the threatened potency of the imperial body politic and the race. [63]

Through

its practical

success in Britain and its connections to ideas of civilization, class

boundaries and British superiority, hygiene became a powerful idea for

Britons during the late nineteenth century, which, as McClintock points

out, was a time of uncertainty and fear of resistance and changing

boundaries.

One

source of both pride and

anxiety was the British occupation of and continuing presence in

Egypt. The situation triggered doubt from British liberals,

even though it was a Liberal government that launched the military

occupation in 1882.

The British in

Egypt

Cholera

broke out in Egypt

just one year after British forces took control of the

country. The officials of the new British protectorate were

still trying to negotiate their role in governing Egypt, even as

Britain’s leaders assured outsiders that the occupation was only

temporary. Lord Cromer, technically Egypt’s second British

proconsul (1883-1907) but in reality its colonial ruler.

Cromer argued that Egypt’s economic and military collapse made foreign

intervention necessary for the survival of British and European

interests in trade routes, especially the Suez Canal. He

maintained that it was impossible for a country that had been

perennially colonized to suddenly take full control of its own

affairs.

So why was it necessary for Britain to intervene as opposed to any other power? Cromer rhetorically poses this question, but to him the answer is self-evident. With their ‘special aptitude’ for dealing with ‘Orientals’, the British were better suited than other colonizers. Even though the occupation led to strained relations with France and dragged Britain into squalid “Continental politics,” nothing could stop a nation that “cannot throw off the responsibility which its past history” proves it was meant to shoulder.[64]

From

the beginning,

occupying Egypt was a conscious choice meant to stave off the possible

chaos of French control of an economically vital territory, although

Harrison makes the point that British power was already predominant by

1876 with the Suez Canal, and invading Egypt was Gladstone’s way of

protecting the empire’s security interests.[65]

More so than for

other colonies, London was directly involved in Egypt’s governance,

especially at the beginning of the protectorate. Tignor

explains that:

since technically Egypt retained the status of a semi-independent state, it was controlled through the British Foreign Office, rather than through the Colonial Office…the control was more strict than customary because Egyptian affairs were unpopular at home with anti-imperialist groups, and the home government was desirous of keeping affairs in Egypt quiet. The home government laid down general lines of policy for its administrators in Egypt to carry out. [66]

This

suggests the classic

image of the foot soldier of imperialism, of lower-class origin and who

sought status and riches in an exotic land. Cholera, however, was dealt

with not by provincial officials, but rather a centralized process led

by the Foreign Office in London and delegated to the medical

specialists they sent to Egypt.

In 1883, Britain dealt with its year-old colonial responsibilities in Egypt under the watchful eyes of liberal critics at home, as well as foreign powers ready to seize upon any indication that the British planned to make their rule permanent ― a contention Britain denied “no fewer than sixty-six times between 1882 and 1922.”[67] Ferguson argues that the occupation was the, “real trigger for the African Scramble,” and signaled to France and other European powers that drastic action was necessary before the British added all of Africa to their empire.[68]

When cholera broke

out at

Damietta in June 1883, the British knew that their policies, and

whatever justifications they provided to bolster them, would have a

significant impact: not only on their integrity of their own trade

routes, but also on Britain’s relationships with its imperial

competitors.

Britain and the

Egyptian Cholera Epidemic of 1883

In

times of panic, the

perception of control over a situation often gives people

comfort. During the cholera pandemics of the nineteenth

century, those who thought the disease was contagious wanted to seal

off Europe’s borders against bacteria from the East. With the

scope of international trade in constant expanding, this was a

near-impossible task, but this fear nonetheless drove agenda of

international sanitary conferences throughout the second half of the

century. When French engineer Ferdinand de Lesseps completed

the Suez Canal in 1869, it acquired huge importance for Europeans who

wanted control over whom and what could enter the continent.

Ships coming from India, the presumed birthplace of Asiatic cholera

according to contagionists, would now pass through a

European-controlled checkpoint. For contagionists, and for

the many Europeans whose knowledge of science was limited but who

believed that one could catch cholera from a diseased person, proper

policing of the Canal was essential.

Therefore,

when the British

gained control of Egypt and partial control of the Canal in 1882, a

potentially delicate situation arose. Britons were

traditionally skeptical of quarantine, believing it to cause more

problems than it prevented. Britain’s exports had risen by 23

percent from 1879 to 1883, and it was a costly inconvenience when ships

were quarantined for as long as several weeks before people and goods

were allowed to disembark.[69] Continental

countries did not have long to wait before they found their fear of

British irresponsibility confirmed. In late June 1883, cases

of cholera began to occur in Damietta, a port city located at the

intersection of the River Nile and the Mediterranean Sea.

Within weeks thousands of people were dead and the disease had spread

to nearby towns.

For

contagionists the cause

seemed clear: some person had become infected in Calcutta, an Indian

city also suffering from a cholera epidemic. He had traveled

to Egypt by ship, disembarked at Suez, and gone to Damietta where his

germs had infected the local population. Soon, suggestions

about the identity of this person were circulating; some even suspected

it was a British government official. Aside from the sanitary

and medical care necessary, two further policies seemed to follow

logically from this theory of causation. First, the Suez

Canal had to be quarantined. Second, the epidemic, just

across the Mediterranean from Europe, provided a chance for scientists

to test corpses and infected matter to try to isolate the cholera

bacterium, an essential next step in understanding the disease and

moving toward a cure.

Unsurprisingly,

the British

officials who controlled the Egyptian government endorsed neither the

contagionist theory nor the policies it spawned. The idea

that cholera had originated in British India and entered Egypt on a

British ship was particularly troubling. The British

therefore took the opposite position, one that enjoyed dwindling

support from scientists: that local environmental factors caused

cholera. They believed that the disease arose, in an

as-yet-undiscovered process, in places of filth and stench, where the

air had a peculiar quality – as if spores of cholera were breeding in

it – and even birds could not stand to live.

In the face of such a situation, the logical approach would be to clean up the local environment and work to change the unsanitary habits of the population. London sent Surgeon General William Guyer Hunter, a medical delegation, and extra British troops to, in turn, investigate the causes of the epidemic, treat patients, and keep order. Treating cholera as a disease of local origin made sense economically for the British, and it was also consistent with certain strains of British culture that emphasized good sanitary practices and competent public health policies as the most effective methods of disease prevention.

larger image

However,

the diplomatic and

scientific debate between Britain and Continental Europe during the

1883 epidemic was not as simple as the description above might make it

appear. Several factors influenced British policy: their

admired sanitary tradition, their presence as the colonial power in

Egypt, and their economic interest in the Suez Canal. But the

British officials also tried to prove their theory and policy

scientifically. Representatives of Her Majesty’s Government

trekked through disease-ridden cities, sought information from local

doctors, and kept careful records partially in order to mount a

credible scientific challenge to the bacteriologists Koch and

Pasteur.

While

Koch discovered the

cholera bacillus in Alexandria in late 1883 and verified his finding in

Calcutta early in the next year, I focus now on the summer of 1883, a

revealing span of time when which the British exploited the lack of

conclusive evidence for germ theory. Moreover, I focus on the way in

which Britain’s rhetoric was structured to present the image of

scientific objectivity, apart from their stated goal of arriving at the

truth of the situation.

The Importance

of Remaining Objective

It has become the fashion to refer to the origin of all epidemics, especially the epidemic of cholera (a disease of whose origin we know almost nothing), to imported contagion; but satisfactory evidence is still wanting that this is the case. [70]

James Mackie, British consular physician

On every occasion of an outbreak of cholera some plausible story has been invented to show how the disease has been imported. [71]

Earl Granville

Facts…lead to the conclusion that cholera, be it called by whatever name it may…has existed in Egypt for some time past…In order to obtain as much information as possible on the subject above referred to, instructions have been issued to the medical officers recently arrived from England to institute cautious and careful inquiry. [72]

William Guyer Hunter

James Mackie, Britain’s delegate to the Egyptian Quarantine Board, writes that any rational observer, accepting the current “fashion” for “imported contagion” without any “satisfactory evidence” would be irresponsible indeed. Foreign Secretary Granville dismisses the importation theory as “some plausible story.” Hunter’s statement is taken from correspondence included in his report on the epidemic. Each is an example of how British officials tried their best to amass evidence in support of the local-origin theory.

British

officials tried to

establish that, first, it would be premature to assign a definite cause

to the epidemic given the current state of science; and second, they

wanted to give the impression that there was a large body of evidence

to support the theory that local factors caused the epidemic. Sir

Walter Frederick Miéville, a British consul in Egypt, illustrates the

first objective when he writes that:

A strong party exists in Egypt intent on showing that the scourge now unhappily decimating a large district of the Delta has been imported from Bombay, and further that the Egyptian Board of Public Health have identified themselves with this party…if it is hoped ever to definitely solve the question of the origin of the disease, the inquiry must surely be approached in an independent spirit, and not with the manifest intention of seeking to establish a foregone conclusion either one way or the other. [73]

Miéville distanced the British from the sordid motives of politics and economics, implicitly attributing to himself and to other officials an “independent spirit,” the ideal of professional science in the modern age. Equally important, Miéville casted the contagionists as a “party” or pressure group, the opponents of independent science, motivated to establish the origin of the epidemic as Bombay for political, anti-British reasons. He portrayed the use of science to support a political goal as inappropriate and un-British.

Sir

Walter Frederick Miéville.

Image

Source: Google

Books

To

make themselves appear

objective, British officials characterized the contagion theory as

prejudicial and politically motivated. Early in the body of his report,

Hunter writes that, “It is hardly worth while to discuss the

oft-repeated and oft-refuted story of the importation of the disease

from India,” and yet he subsequently devotes the balance of the report

refuting that very same “story.”[74]

Had contagion not

gained so much sway in the minds of Europeans and Egyptians, Hunter

presumes that his task would be much easier:

It is this fixed idea of importation that renders inquiry so difficult, and causes all the believers in such a hypothesis to ignore testimony which to an unbiased mind would be plain and clear. It does not fall to every one’s lot to be able to shake off preconceived opinions…and to accept the facts as they see them; could they do so, I cannot avoid the conclusion that little difficulty would have been experienced in supplying the links in a chain, which probably, at this distant period, will never be found. [75]

Importation

is associated

with the language of the superstitious, pre- scientific past: “fixed

idea,” “believers,” “preconceived

opinions.” The scientific term,

“hypothesis,” suggests that importation is just a theory,

as-yet unproven. By contrast, those who

are able to remain “unbiased” and conduct

“inquiry” are “plain and clear,” “accept[ing] the

facts.” Hunter also notes that “it does not fall to every one’s lot” to

remain unbiased, an evocative phrase. Are some people

naturally less capable of objective thought than others? Most

Europeans would have agreed that Egyptians, being “Orientals,” fit that

description. In fact, some Egyptians did support the

importation theory, actively resisting Britain’s handling of the

epidemic and its presence in Egypt in general. However, in

the above passage Hunter characterizes all supporters

of the importation theory as biased, superstitious non-Westerners.

Britain

was undoubtedly not

the only country to use science as a political tool. But it

was, perhaps, unmatched in its hypocrisy: Despite its rhetoric of

objectivity, almost every observation in British correspondence and

reports supports the local-origin theory. As intent as some

were to prove that cholera came from India on a British ship, the

British were equally intent to prove that it did not.

The

pursuit of this goal

involved the use of many kinds of evidence, weighted towards but by no

means confined to the atmospheric observations that characterized the

miasma theory. Unsanitary lifestyles [76],

filthy water [77],

disposal of waste, animals

and corpses [78],

burial practices [79],

animal behavior

[80],

the weather (“the sky was

lead-colored, the atmosphere oppressive…the sparrows deserted the town,

and did not return until the epidemic was on the decline”[81]),

patterns of diarrhea

occurrences [82],

the movement of the moon [83],

and other factors were

eagerly considered by the British in the effort to give the impression

of reasonable proof for the local-origin theory.

This

contradiction between

this effort and the concurrent claims to objectivity went almost

unacknowledged. Dr. Mackie did admit that “it may be

said” that his support of the local-origin theory “is purely

speculation,” but he seems to find the reply self-evident: “I

reply that it is less speculative than that the disease was imported

direct from Bombay.”[84] We can see the

results of the contradiction in Hunter’s dealings with several doctors

in Egypt, both foreign and Egyptian. Hunter was looking for

information that pre-epidemic cases of a cholera-like diarrhea known as

“cholerine” were actually mild cholera, hidden – purposefully or not –

by a euphemism. This would establish that whatever caused

cholera had been present in Egypt before the official start of the

epidemic and, therefore, before the arrival by ship of agents that

contagionists had named as potential causative elements.

Dr.

Sierra was one of those

who supplied Hunter with records of cholerine cases, and one of several

who hoped that his reports would not be used to disprove the theory of

importation. In his letter to Hunter, which Hunter enclosed

in his report to the Foreign Office, Sierra expressed concern over the

possible uses of his evidence:

Importation should…be proved by careful inquiry before being admitted; yet, on the other hand, the theory of the production of the germ on the spot leads to conclusions which are perhaps even rasher still from the point of view of scientific logic…I think that the present state of science urges us to be extremely reserved in affirming either theory, if we wish to act in the rigorously scientific manner in which the Tyndals, Pasteurs, and other great men proceed in their investigations as to ferments and their propagation. [85]

Hunter

portrays this

reluctance to rush to conclusions as evidence that the theory of

importation had such a strong hold over some Continentals and Egyptians

that even the evidence of their own eyes could not sway them from the

position:

Dr. Ambron [a doctor who held similar views to Sierra], like the majority of the medical men in this country, is a firm believer in the importation of the disease from the delta of the Ganges, and unless it can be so traced, he declines to accept what would seem to me to be the evidence of his own senses. [86]

“Dr. Sierra’s facts are of great value,” Hunter concludes, but “his conclusions…I cannot accept.”[87] Without any acknowledgment of the irony of the situation, Hunter’s spirited backing of the local-origin theory becomes dispassionate and objective, while Sierra’s refusal to endorse either theory on the grounds of inadequate evidence is a sign of bias and foolish allegiance to a “fixed idea.”

In

London, Earl Granville,

the Foreign Secretary, received Hunter’s reports with

“interest” and “satisfaction” and

worried about escalating costs and negative press.[88]

On at

least one occasion, Granville asked specific questions of his

officials, hoping to add his own ideas to the case against

importation. “Your Lordship asks me whether, before the

outbreak of the cholera epidemic at Damietta, I have received

intelligence as to the unsanitary state of that town,” replied Sir

Edward Malet, Egypt’s proconsul until September 1883 (he was succeeded

by Lord Cromer), to Granville:

I was not aware that Damietta was in a worse sanitary condition than other towns…It may be as well to state, in this connection, that there is good evidence that the epidemic did not originate at Damietta, and that before it broke out there it existed in villages in the neighborhood and other parts of Egypt. [89]

Granville,

it appears,

sought to buttress Britain’s pseudo-scientific process by obtaining

confirmation that Damietta, the town where the epidemic broke out, was

dirtier than other towns in Egypt. Malet hastened to reply

that although Damietta was not noticeably less sanitary than other

Egyptian towns, the epidemic might have started in other villages that,

presumably, were particularly dirty.

In

addition to Britain’s

pejorative portrayals of the importation theory, the British treated

quarantine itself – the usual reaction to importation – as a policy

provoked by panic rather than reason. The sanitary cordons

around Egyptian cities earned a reputation in the British media as

disasters, leaving hundreds of people without access to medical care or

supplies. Quarantine itself was also vilified. In a

circular to British diplomats at Continental consulates, Foreign

Secretary Granville laid out the government’s response to “the tone

adopted by a great number of the Continental newspapers upon the

subject of the recent outbreak of cholera in Egypt…Her Majesty’s

Government would not have considered it advisable under ordinary

circumstances to notice similar attacks had it not appeared that they

are exciting a feeling against this country unjustified by facts.”[90]

Granville

impressed upon the diplomats that “quarantine is not only useless but

actually hurtful,” and that sanitary cordons:

[are] calculated, for moral and physical reasons which are easily understood, to increase the number of persons attacked, to intensify the virulence of the disease…while the unfounded belief in the security given by quarantine discourages the adoption of those sanitary measures which alone are proved to check the spread of the epidemic. [91]

Granville criticizes the panic and suffering caused by sanitary cordons and suggests that the cordons the were implemented with malicious intent. Granville does not elaborate on this remarkable accusation, so it is difficult to tell whether he suspected that the mixed Egyptian-European health authorities were trying to increase the chaos that they could then blame England for creating, or whether he suspected some other motive.

Either way, cordons and quarantines were attacked by the British government and press as useless, harmful and irrational. Mackie wrote that fear of quarantine led “Europeans as well as Egyptians” to misrepresent cases of cholera-like diarrhea before the epidemic: “This is the outcome of quarantine and one of the abuses which its irrational employment leads to.”[92] According to Mackie, the fear of quarantine and “sanitary cordons” silenced the truth because doctors, not wanting Egypt to be placed in quarantine, misrepresented pre-epidemic cases of cholera as cholerine or diarrhea instead. Quarantine not only caused panic and other uncivilized behavior, it also stifled the course of objective inquiry.

Although

Hunter advised the

British government to withdraw the sanitary cordon around Alexandria,

the British refrained, knowing that panic and possibly riots or

rebellion would result,[93] but

they resented the decision; Mackie wrote:

It has been proved that the fancied safety by quarantine creates a carelessness to all other sanitary improvement…I most firmly believe that, had the money spent on, and the attention given to, quarantine for many years past, been spent on proper sanitary improvements… [and] proper State supervision of public health, the present epidemic of cholera would not have been devastating Egypt. I would put the question in a practical, if not a scientific way, for science as yet has taught us little Earl Granville about cholera. [94]

In

other words, quarantine

breeds panic and carelessness, and although “science” was not

sufficiently advanced to draw a bacteriological conclusion as to the

cause of the epidemic, the “practical” evidence indicated

otherwise. Journalists and some scientists in

Britain echoed this sense that British sanitary efforts to fight

cholera were on an equal footing with Continental attempts to find the

bacterium that caused it. One lecturer, a Dr. Evans, told his audience:

The French Government has granted 50,000 francs to the celebrated pathologist, Pasteur, in order to send out a scientific mission to Egypt to investigate whether cholera be not due to the development of a microscopic animal in the human body…There are many English medical men at present in Egypt, also representatives of many leading civilized countries, so that ere long we may hope to have some reliable information regarding this disputed question. [95]

The rest of Evans’s talk is more clearly partisan, following Hunter’s lead: an explication of the various other factors – physiological, meteorological, even geological – anything that could mitigate the unfortunate tendency to give “too much attention…to the germ theory of disease, which is often erroneous and speculative.”[96]

Even

after Koch’s discovery

of the cholera bacillus, the equivocation and skepticism continued,

with a government-sponsored report indicating holes in Koch’s argument

and arguing that germ theory caused irrational panic among

Europeans. Aside from some reasonable criticisms of Koch’s

findings, the report noted:

It would be quite unjustifiable to maintain that the extraordinary panic which seized a section of the French and Italian nations on the visitation by the cholera in the summer of 1884 was caused by this theory of the commabacilli [cholera bacteria, which were shaped like commas], but considering the authoritative position that Koch occupies, and considering the very decided way in which Koch, his Government, and the daily and most of the medical press gave expression to this view, it is not unreasonable to say that the panic, although not caused, derived material support from it, for has it not been preached from day to day that the cholera evacuations are full of commabacilli, and that the commabacilli are the contagium of cholera? What, after this, is more natural than that the general public, reading such statements as coming from the highest authorities, should take up and spread the cry? [97]

Therefore panic in the press and among the population, according to the report, could be not just partly ascribed to Koch’s discovery, but partly blamed on it.

In

contrast to the panic created by quarantines and

contagionism, the British portrayed sanitary policy as civilized and

effective. In the Literature Review, I explored why some

British officials placed so much faith in “proper” hygiene and

practical efforts to stop cholera. How were these ideas used

in 1883?

Common Sense:

The Practical Man’s Cure for Cholera

A

confluence

of factors

influenced the British government’s confidence in their hygiene-focused

approach to fighting cholera. First, they had the benefit of