|

|

|

Wang Tingyun (1151-1202

AD), Secluded

Bamboo and Withered Tree

| SOURCE:

Zhongguo meishu

quanji, Huihua bian3: Liang Song huihua, shang

(Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 1988), p. l 57, p. 158. Collection of

Fujii Yurinkan, Kyoto. Section of

handscroll, 15"h. |

|

|

Designing a garden was seen as an

intellectual pursuit, and often took a lifetime to perfect. The garden

was an unfinished work constantly under revision and improvement. In its

aesthetic goals and the symbolism employed, it was closely linked to

activities such as Chinese painting.

To an individual of cultivated tastes, the scholars'

gardens of the Ming represented a culmination of many values expressed

in other art forms like painting, calligraphy, and poetry. Landscape

painting in particular was very influential on garden design. |

|

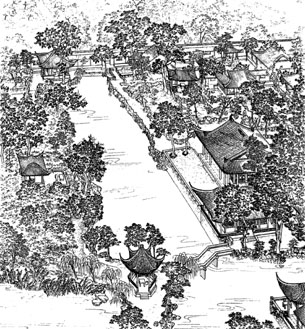

The aesthetic goals of a Chinese garden were not the same as those in

typical Western gardens. Compare below two views of the same garden, the

Garden of the Artless Official, located in Suzhou, Jiangsu

province.

What seem to be the dominant elements or most distinctive features?

Are these different from parks or gardens with which you are more

familiar?

|

|

|

|

|

A corner of the Garden of the Artless Official

|

| SOURCE:

Photograph courtesy of Jerome Silbergeld. |

|

Bird's eye view of Garden of the Artless Official

| SOURCE:

Liu Dunzhen. Suzhou gudian yuanlin (Nanjing: Zhongguo

jianzhu gongye chubanshe, 1979). |

|

|

An

overall impression of tidiness and precision rarely strikes the visitor

to a Chinese garden. Unlike its Japanese counterpart, the Chinese garden

is enjoyed for its apparent disorder. Most gardens try to incorporate

aspects of rusticity and spontaneity inherent in nature. This is a

similar goal to that found in many Chinese paintings where subjects,

such as gnarled trees or rigid bamboo (see the painting at the top of

this page), are often chosen for their character. An

overall impression of tidiness and precision rarely strikes the visitor

to a Chinese garden. Unlike its Japanese counterpart, the Chinese garden

is enjoyed for its apparent disorder. Most gardens try to incorporate

aspects of rusticity and spontaneity inherent in nature. This is a

similar goal to that found in many Chinese paintings where subjects,

such as gnarled trees or rigid bamboo (see the painting at the top of

this page), are often chosen for their character.

|

|

Treebark

pavilion, Chongqing (Sichuan province)

| SOURCE:

Pan Guxi, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji, Jianzhu yishu

3: Yuanlin jianzhu (Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye

chubanshe, 1988), p. 181. Rustic pavilion, Green

Wall Mountain Pavilion, Guan county, Sichuan province. |

|

|

What positive value do you think disorder might play

in a Chinese garden?

|

|

The

personality of the garden's designer determined to a large extent the

types of buildings, plants, and other features that were selected. The

exterior environment might also influence how rustic or elegant a garden

was in its architecture and decorative details. The

personality of the garden's designer determined to a large extent the

types of buildings, plants, and other features that were selected. The

exterior environment might also influence how rustic or elegant a garden

was in its architecture and decorative details.

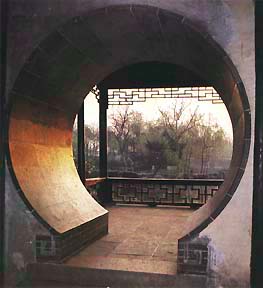

Compare the Treebark pavilion (above) with the view

through this gate in a city garden.

How do they each take advantage of the natural

surroundings?

| HINT:

Consider the ways views are framed by these different

architectural structures. |

|

|

Moon gate, Garden

of the Artless Official, Suzhou

| SOURCE:

Pan Guxi, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji, Jianzhu yishu bian 3:

Yuanlin jianzhu (Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe,

1988), pl. 88, p. 90. |

|

|

|

|

Another

preference in garden design is to use shapes that metaphorically refer

to elements in nature; some of the subtlest examples of this practice

are also the most highly appreciated. The wall opening, above, is one

example of an allusion to nature. Another

preference in garden design is to use shapes that metaphorically refer

to elements in nature; some of the subtlest examples of this practice

are also the most highly appreciated. The wall opening, above, is one

example of an allusion to nature.

What might be some reasons for undulating walkways or

walls in a garden like the one on the right?

| ANSWER:

Like pavilions, crooked pathways are intended to make a visitor

slow down to better appreciate views. In terms of fengshui,

undulating paths prevent bad spirits, who can only travel in

straight lines, from progressing forward. |

|

|

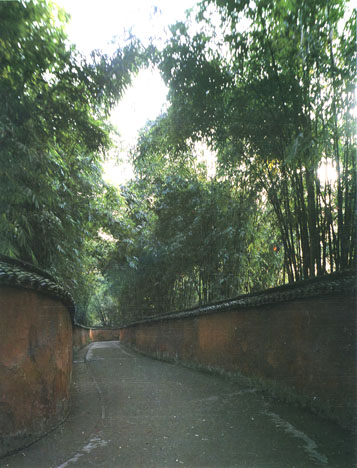

Wall and bamboo at

the Shrine of Count Wu (Zhuge Liang), Chengdu (Sichuan

province)

|

| SOURCE: Pan Guxi, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji, Jianzhu yishu bian 3:

Yuanlin jianzhu (Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye chubanshe,

1988), p. 176. |

|

|

|

|

|

Covered walkway at the Garden of the

Master of Nets, Suzhou

(Jiangsu province)

| SOURCE:

Pan Guxi, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji, Jianzhu yishu

bian 3: Yuanlin jianzhu (Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu

gongye chubanshe, 1988), p. 107. |

|

|

Special thought was given to planning the Chinese garden

for year-round enjoyment. It was thought that the garden should have a

distinct look in each different season of the year.

How do you think the planners incorporated this

preference into their final design of this garden?

|

|

Rejoicing in the

West Tower, Chongqing (Sichuan province)

| SOURCE:

Pan Guxi, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji, Jianzhu yishu

3: Yuanlin jianzhu (Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongye

chubanshe, 1988), pl. 88, p. 90. Autumn scenery viewed

from Rejoicing in the West Tower, Chongqing (Sichuan province). |

Move on to Garden

of the Master of Nets

|