| Many of the paintings

made at court served political purposes. Emperors liked to see

paintings that testified to the effectiveness of their rule, signs that

the people were prosperous and happy, or that Heaven had responded to

their virtue by sending auspicious omens. Another favored

topic was stories of noble or exemplary individuals, especially ones

that had messages for rulers. Emperors also commissioned

illustrations of the classics, which confirmed their support of

learning. All of these uses of painting were especially prominent

during the reign of the first emperor of the Southern Song, Gaozong, who

had to convince the literati that even though they had not been able to

push back the Jurchen and retake the ancient homeland of China, they

were the legitimate government, the protector of ancient traditions.

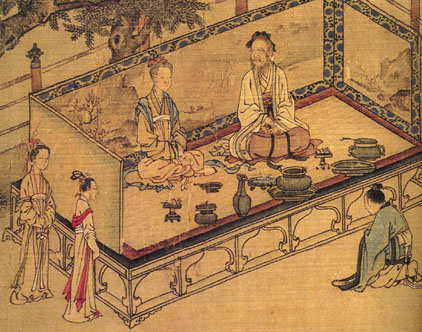

The scene below is the central section of a large hanging scroll illustrating the story of a loyal minister of the Han dynasty. At a court audience Zhu Yun inappropriately asked for the emperor's sword. Outraged, the emperor sentenced Zhu to death, but when his guards tried to drag Zhu away, he protested vehemently, grabbing onto the balustrade, and insisting that he be put to death immediately. One minister did not object, but another intervened to defend Qu's character and admonish the emperor. |

|||

|

Why would an emperor like Gaozong have wanted a painting like this to be produced at his court?

|

|||

|

|||

|

|||

The

artist of this painting, Ma Hezhi, was a court painter under Gaozong who

illustrated many classical texts. Here is one scene from his

illustrations to the Classic of Filial Piety. The

artist of this painting, Ma Hezhi, was a court painter under Gaozong who

illustrated many classical texts. Here is one scene from his

illustrations to the Classic of Filial Piety.

Note the landscape painted on the screen. Who do you think each of the people in this scene represent? Why aren't the older couple sitting on chairs? |

|||

Ma Hezhi,

"Illustrations of the Classic of Filial Piety," detail

|

|||

|

|||

| Depictions of peace and prosperity also served the political needs of the court. Paintings like Zhang Zeduan's The Spring Festival Along the River or Li Song's Knickknack Peddlar could be read by emperors as evidence of the success or their governments. So too could depictions of busily engaged farmers, like the one below. | |||

|

|

|||

|

Anonymous Song artist, Tilling and Harvesting

|

|||

| The Yuan court did not commission as many narrative paintings as the Southern Song court had, but the painting below may have appealed to the Mongol rulers not just for its story, but also for its depiction of animal combat. | |||

|

|

|||

|

Anonymous Yuan artist, Clearing the Mountains

|

|||

| For a closer look at the central scene: | |||

|

|||

|

Move on to Scholars' Painting

|