|

It became quite common among literati artists of the Yuan

to allude to earlier painting styles in their paintings. They were

creating, in a sense, art historical art, as their paintings did not

refer only to landscapes, but also to the large body of earlier

paintings that their contemporaries collected and critiqued.

Another trait of Yuan literati landscapists is that they did not hide

the process of their painting, but rather allowed the traces of their

brushes to be visible, going considerably further in this direction than

painters of the Song.

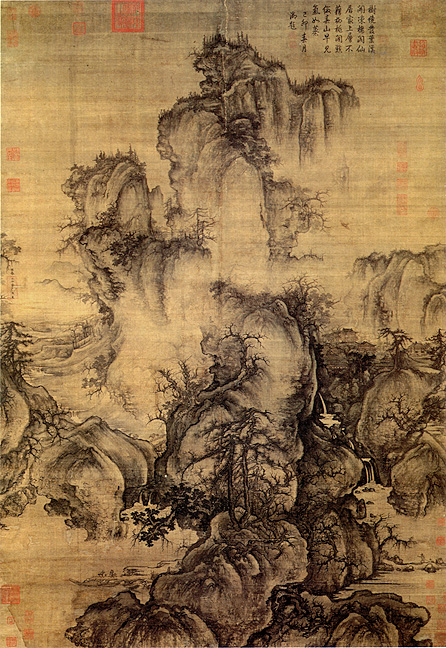

In Ming times, the three painters illustrated below, Huang Gongwang,

Ni Zan, and Wang Meng were designated the Four Masters of the Yuan

period (along with Wu Zhen, whose paintings of bamboo appear in a later

section).

From the three paintings illustrated below, do these painters

share much? Do they have similar goals, of employ similar methods?

Or are you struck more by the differences among them?

|

|

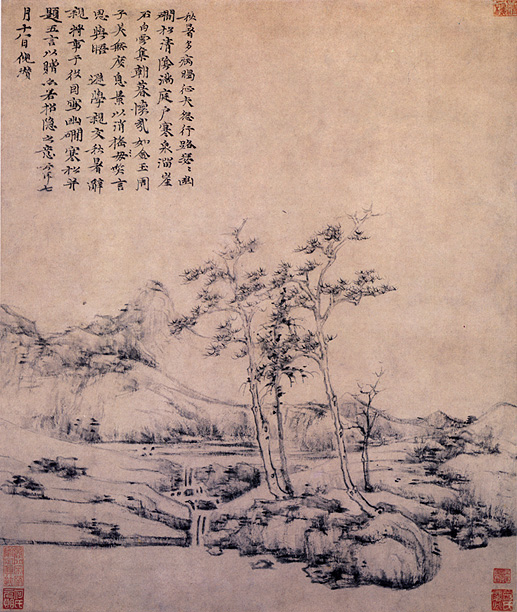

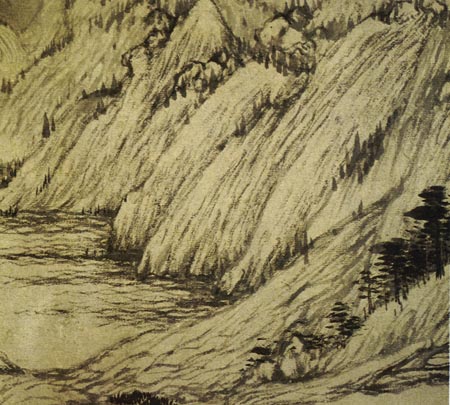

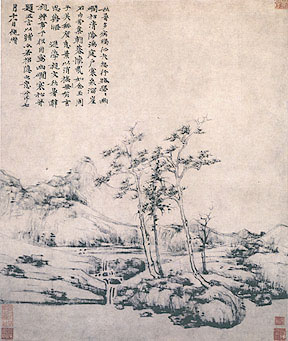

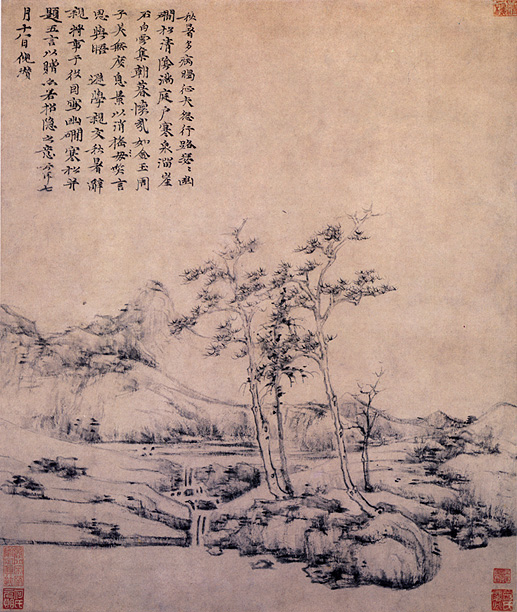

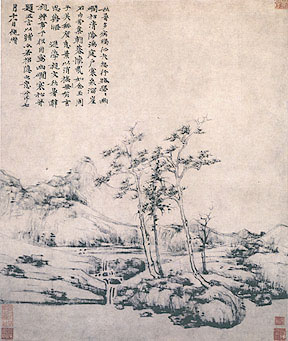

This

artist, Ni

Zan, stripped down his technique to all but the most

essential brushstrokes. His inscription of a poem, by contrast, is

rather lengthy. In it he states that he did the painting as a

present for a friend leaving to take up an official post, to remind him

of the joys of peaceful retirement. This

artist, Ni

Zan, stripped down his technique to all but the most

essential brushstrokes. His inscription of a poem, by contrast, is

rather lengthy. In it he states that he did the painting as a

present for a friend leaving to take up an official post, to remind him

of the joys of peaceful retirement.

What would the inscription have added for viewers

other than the recipient?

For a larger view, click here.

|

|

Ni Zan

(1301-1374), Still Streams and Winter Pines

|

|

SOURCE:

Fu Xinian, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji, Huihua bian 5: Yuandai

huihua (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 1989), pl. 120, p. 173.

Collection of the National Palace Museum, Beijing. Hanging

scroll, ink on paper, 59.7 x 50.4 cm

|

|

| A larger view: |

|

| MORE: Ni

Zan was from a wealthy family and until middle age was able to devote

his life to scholarship and artistic pursuits. He built a

pavilion to hold his great library and collection of antiques,

paintings, and calligraphy and entertain his many quests. A

series of floods, droughts, and consequent famine and uprisings

brought this ideal existence to an end as the Yuan dynasty began to

unravel. For twenty years, beginning in 1351, Ni Can wandered

with his family through the southeast, living in a houseboat or

staying with friends.

Scholars read Ni Zan's

paintings of simple, almost barren, unpeopled landscapes as expressive

of a longing for a simpler world. |

|

|

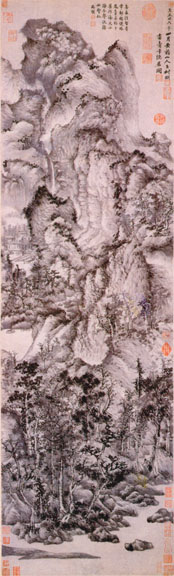

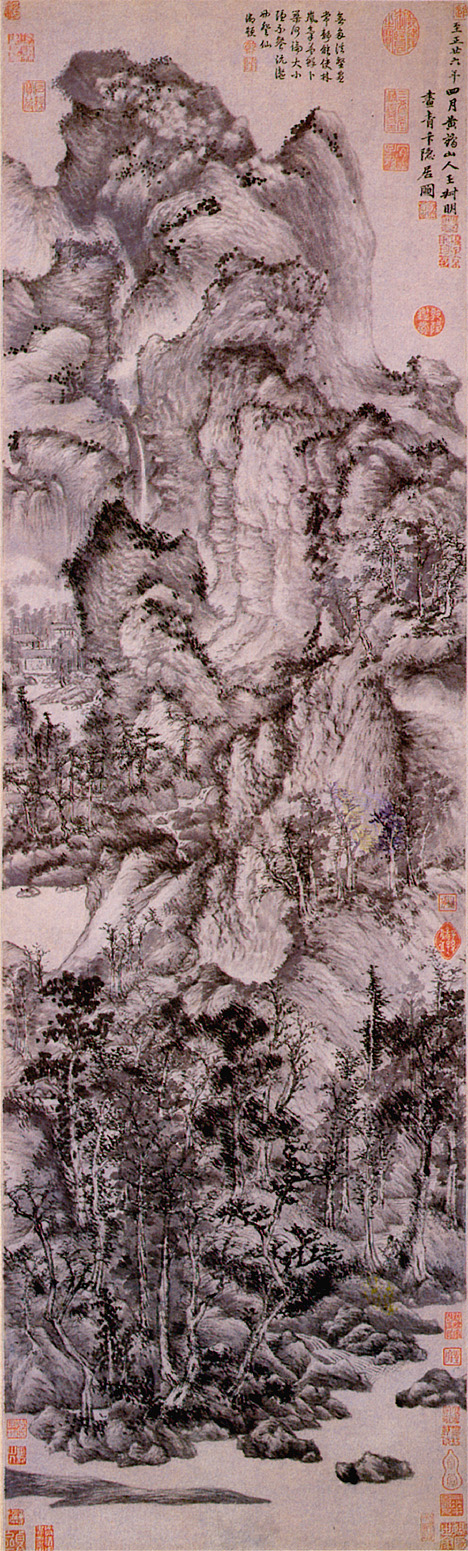

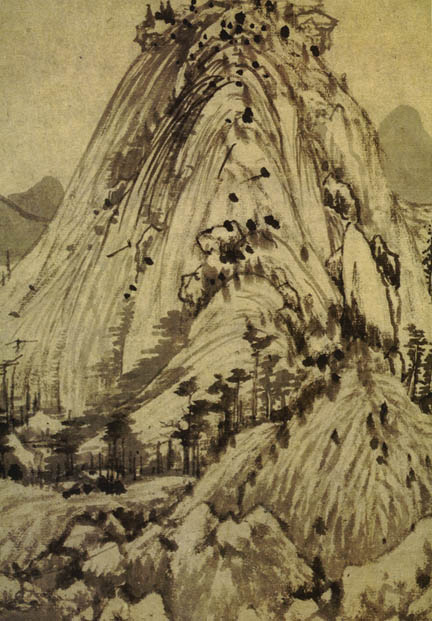

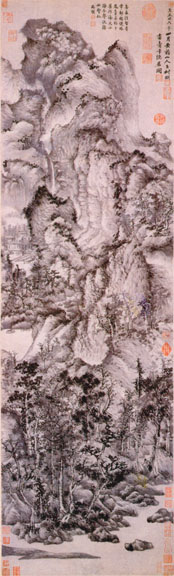

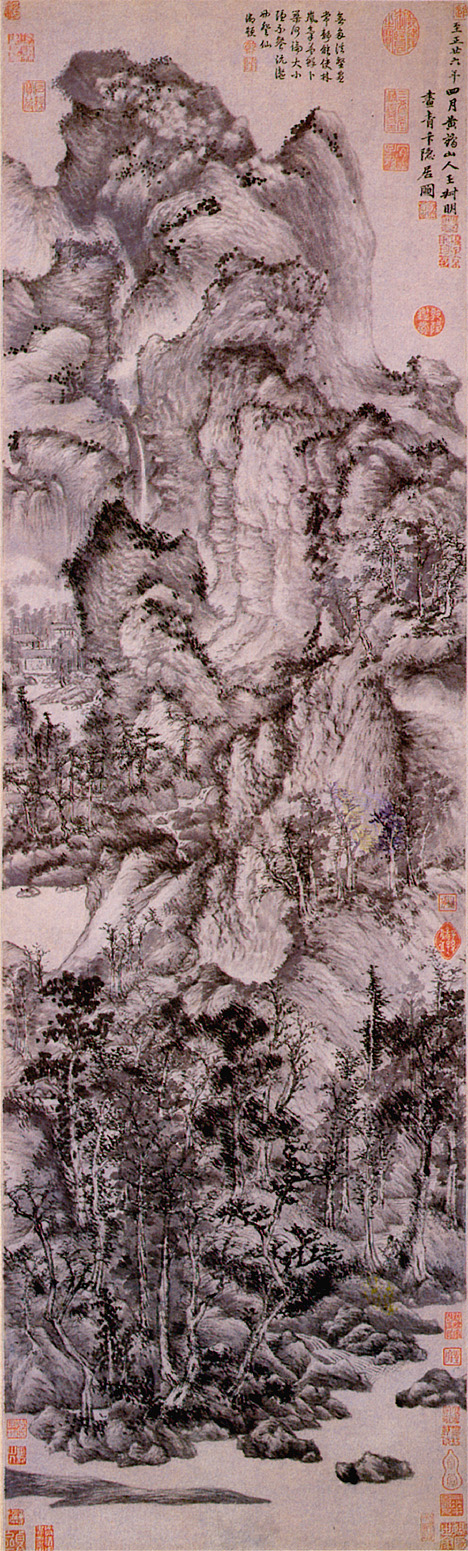

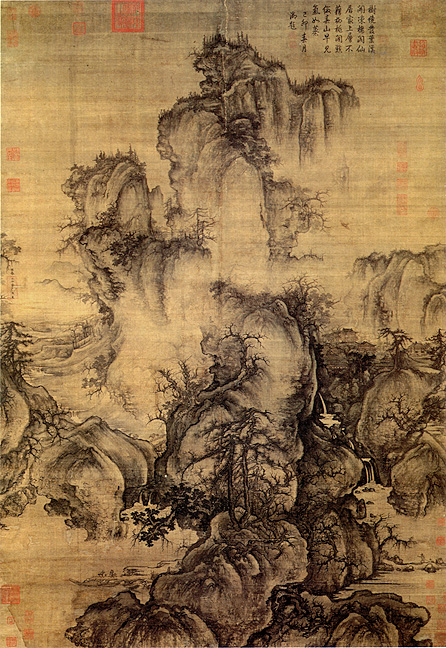

Done in 1366, just two years before the fall of the Yuan

dynasty, this painting represents the villa of a relative of the

painter, Wang Meng (ca. 1309-1385).

| MORE:

Wang Meng (ca. 1308-1385) the youngest of these painters, was

born long after the Song had been defeated and lived into the

Ming dynasty. His adult years were a time of turmoil as

the Mongol government lost control of most areas of China.

After brief service as an official, Wang Meng spent most of his

time in Hangzhou or Suzhou with other poets and artists.

Wang Meng's brushwork

is markedly different from Ni Zan's. He used many

different types of strokes, packed close together to give a

sense of nervous energy.

|

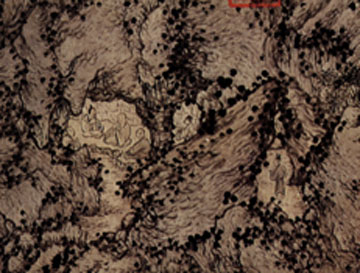

To see a larger view of this dense painting, and to

compare it to the Guo Xi viewed earlier, click

here. [In the guide, below]

| MORE:

By adopting so many of the compositional features of the

monumental landscapes of the Northern Song, such as the dominant

central peak, Wang Meng is able to implicitly compare the

turbulent world he portrays to the stable world of the past.

Where the Guo Xi painting had been traversable, this painting is

full of ambiguities and distortions. Even the brushwork

seems more restless. |

Wang Meng (ca. 1309-1385), Secluded

Dwelling in the Qingbian Mountains

| SOURCE:

Fu Xinian, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji, Huihua bian 5:

Yuandai huihua (Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 1989), pl. 125, p.

179. Collection of the Shanghai Museum. Hanging scroll, ink on paper, 140.6 x 42.2 cm |

|

Compare the composition and brushwork of this painting

to the Guo Xi shown below.

What are the principle differences between the two?

In what ways does Wang Meng's painting seem more a

scholar's painting?

|

|

|

| SOME

THOUGHTS: By adopting so many of the

compositional features of the monumental

landscapes of the Northern Song, such as the

dominant central peak, Wang Meng is able to

implicitly compare the turbulent world he portrays

to the stable world of the past. Where the

Guo Xi painting had been traversable, this

painting is full of ambiguities and

distortions. Even the brushwork seems more

restless. |

|

|

|

|

This

artist, Ni

Zan, stripped down his technique to all but the most

essential brushstrokes. His inscription of a poem, by contrast, is

rather lengthy. In it he states that he did the painting as a

present for a friend leaving to take up an official post, to remind him

of the joys of peaceful retirement.

This

artist, Ni

Zan, stripped down his technique to all but the most

essential brushstrokes. His inscription of a poem, by contrast, is

rather lengthy. In it he states that he did the painting as a

present for a friend leaving to take up an official post, to remind him

of the joys of peaceful retirement.