| Scholar painters were not necessarily amateur painters, and many

scholars painted in highly polished styles. This was particularly

true in the case of paintings of people and animals, where

scholar-painters developed the use of the thin line drawing but did not

in any real sense avoid "form likeness" or strive for

awkwardness, the way landscapists often did.

One of the first literati to excel as a painter of people and animals was Li Konglin in the late Northern Song. A friend of Su Shi and other eminent men of the period, he also painted landscapes and collected both paintings and ancient bronzes and jades.

Figures done with a thin line, rather than a modulated one, were considered plainer and more suitable for scholar painters. |

||||

|

Li Gonglin, Five Tribute Horses, detail

Horses were a popular subject for painters. From the picture above and those here and below, can you think of any reasons why horses attracted painters? |

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

| Gong Kai, the painter of the painting below (and another later), was an extreme loyalist, who had held a minor post under the Song but lived in extreme poverty after the Mongol conquest, supporting his family by occasionally selling paintings or exchanging them for food. By contrast, the painting below Gong's is by a slightly later painter, Ren Renfa, agreed to serve the Yuan court and even painted on official command, making him not that different from a court painter. | ||||

|

|

||||

|

Gong Kai (1222-1307?), Emaciated Horse

|

||||

|

What symbolism do you suppose an emaciated horse carried? Why would it appeal both to scholars aloof from the court and scholars at court?

|

||||

|

Note the difference in the techniques used by Gong Kai and Ren Renfa to paint the horses. Which is more in keeping with scholar painting styles? |

||||

Ren Renfa (1254-1357), Two Horses, detail

|

||||

|

Gong Kai also painted a long handscroll of the demon-queller Zhong Kui, a popular topic. Can you think of a political interpretation of this choice of subject matter?

|

||||

|

To see the full scroll, click here [given below in Teacher's Guide].

|

Gong Kai (1222-1304), Zhong Kui Traveling with his Sister

|

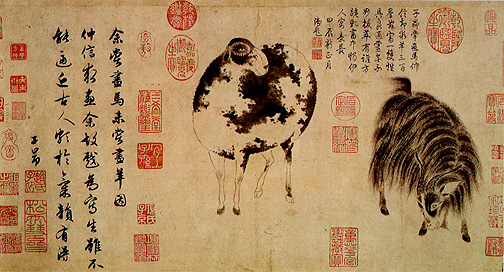

The

inscription on the left, by the artist, Zhao Mengfu, does not give any symbolic

significance to the subject of goats and sheep. The Chinese word that

covered both animals, however, was a homophone for "auspicious." The

inscription on the left, by the artist, Zhao Mengfu, does not give any symbolic

significance to the subject of goats and sheep. The Chinese word that

covered both animals, however, was a homophone for "auspicious."

|

Chen Lin (Yuan), Water fowl

Compare Chen's way of depicting a duck, below (above in detail), to that of the court artist whose painting we saw earlier. Besides the difference between the use of color in one and reliance on monochrome ink in the other, what other differences in technique do you see?

|