A contrarian’s tale

“And then I ran out of money. That,” says Scott McAdams (MBA 1986), “was when I knew it was time to get serious about finding a job.”

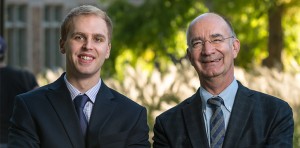

Chris Ackerlund, recipient of the McAdams Wright Ragen, Inc. Endowed Scholarship, with Scott McAdams (MBA 1986).

A few months prior to running out of funds, McAdams had graduated from Cornell University with degree in mechanical engineering. The year was 1979. Jimmy Carter was president. McDonald’s introduced the Happy Meal. The economy was in a lull and jobs were hard to get. Oil prices were high.

McAdams was fascinated by alternative energy and passionate about becoming a solar engineer, so, after graduating, he came west. First he drove to Colorado for some interviews. He then went to New Mexico. He stayed with some relatives and lined up some more interviews.

All of the interviews led him to the conclusion that jobs in the field were demanding PhDs. This conclusion coincided with running out of money. McAdams started to send out resumes further afield.

Hello, Scott. This is Boeing.

One of the resumes got him an interview with Boeing, which led to another. “Everything happened over the phone,” says McAdams. “They even hired me over the phone. It was as if they were thinking, ‘We need engineers and you passed muster.’”

He had never been to the Northwest, but accepted the job offer and drove to Seattle with everything he owned in January of 1980.

McAdams found Boeing to be an incredible company, but a bit stifling. “If you were young and ambitious at that time—and I was—it wasn’t a great place to be. There were guys who had been there for 20 to 30 years and they weren’t going anywhere,” says McAdams. “It just wasn’t moving fast enough for me.”

McAdams sought other work, but found it hard to find. He believes a good part of it was a prevailing attitude in the area at the time of Boeing engineers. “There was an unspoken mark against you if you worked at Boeing, if you were part of the ‘lazy B,’ as many people called it.”

A well placed bet

McAdams decided to pursue an MBA and applied to a number of schools. With acceptance letters in hand, and a desire to stay in Seattle, he made his choice. “At the time, Seattle was a provincial enough economy that if you wanted to work in the Northwest you were better off going to school in the Northwest. So I did,” says McAdams. “It was the bet I made and it worked out.”

Once he was in school, the decision to pursue finance as a concentration was easy. “As my wife reminds me, even at Boeing I would read the WSJ everyday cover to cover. Even as an engineer, I wanted to be a stock analyst.”

At the time, there weren’t many investment firms in Seattle. He interned with Foster & Marshall (where he met both Michael and A.O. Foster). Upon graduating, he went to work for Cable, Howse & Ragen as a junior analyst.

“My starting salary was half what I had been making as an engineer two years before. But at the time, the finance community was so small and if you wanted to get your foot in the door, you started at the ground floor,” says McAdams. “I was so excited to have the job, it didn’t matter.”

The early days provided some lessons that couldn’t be taught in school, even by Karma Hadjimikilakis and Bill Alberts, his favorite professors in the program. He learned a lot, but didn’t realize the courage it would take.

“It’s something you have to experience and it’s brutal. Classic problem you run into: a stock drops 50%, you do your analysis and think it must be the bottom, so you build a position. Then you realize it’s not the bottom when it drops another 50% and it turns out your assumption wasn’t accurate. And you’re faced with a big decision–do you double up or sell and take the loss? When you’re in this business and you come in in the morning and one of your stocks has done that, it’ll be the worst 24 hours of your life.”

You’re all fired

Within a couple of years, he returned to work at Foster Marshall, a subsidiary of Shearson American Express at time, but which still had a local research staff led by John Mackenzie.

“Shearson Lehman had a huge research department in New York, which was being led by Peter Cohen, and they didn’t really need us in Seattle. And unlike the team in New York, we were practicing contrarian value based investing,” says McAdams.

In 1988, the differences in investing approach came to a head. The New York research department was recommending the sale of a particular security. The Seattle office was recommending a buy on the same security. “Someone must have marched into Peter’s office and said, ‘What are these guys doing in Seattle? They’re confusing the clients.’ He called us that day and fired the whole department.”

According to the Seattle Times, that same year, Tom Cable and Elwood “Woody” Howse “decided to focus exclusively on their Bellevue-based venture-capital firm, investing in new, cash-hungry companies.” That provided an opening for John Mackenzie, with his small team of recently laid-off analysts, to approach Brooks Ragen. Ragen MacKenzie, formed in 1988, prospered and grew becoming a dominant regional firm in the Northwest. The firm was eventually sold to Wells Fargo in 2000, which later folded the operation into its larger brokerage unit.

We need a name

In late spring of 1998, Ragen made a call to McAdams. He wanted to start another firm.

“At the time, Brooks was in his 60s,” recalls McAdams. “He said, ‘I’ll supply the capital, my name and contacts, and you do all the work.’ ”

The men pulled a staff together and found a location, but ran into a dilemma prior to opening their doors. They were in need of a name. “Because of the terms with our prior firm, we couldn’t use our names together. It sounded too much like Ragen Mackenzie,” says McAdams. “We needed another name.”

They wanted to find someone with a name that meant something in Seattle. At the last hour, the duo asked Bagley Wright if they could include his name. Wright was well known as a real estate developer as well as a philanthropist and patron of the arts. He agreed to lend his name and became a shareholder and a member of the board.

Contrarian value investing

“Contrarian value based investing tends to work because it isn’t used very often,” says McAdams. “It’s about buying when companies are down and out and no one else wants them. You’re looking for the intrinsic value and trying to guess what Wall Street is thinking. Practiced with discipline it tends to be, on a risk adjusted basis, a good way to manage retail money.”

He is quick to note that the approach is not going to make a 20-something a millionaire, but for someone with a million dollars in their 60s it’s a good way to protect it and make some money.

“There’s always been this little enclave of people in the northwest that believe in this type of investing,” says McAdams. That little enclave helped McAdams Wright Ragen become a big success. The firm experienced 15 straight years of growth of approximately 20% every year.

During that fifteenth year of growth, McAdams along with his partners and staff decided to celebrate in a unique fashion. Rather than throw a lavish party, they endowed a scholarship at the Foster School, the educational institution that educated many of them, to create a means by which to encourage students to pursue a finance career. Of equal importance to McAdams and his partners was the desire to contribute to the most vulnerable parts of the community by designating the scholarship for students affiliated with the university’s Educational Opportunity Program.

The closing bell

As the firm celebrated their fifteenth year of business and growth, they were approached by Milwaukee-based Robert W. Baird & Co. with an offer to buy the firm.

“Brooks and I decided that if we were ever going to sell, the firm would have to be of high caliber and high integrity,” says McAdams. ”Unfortunately on Wall Street, there is a shortage of those things. We were particular and Baird passed the test. We worked with them to understand the values of our firm and our clients. It made sense and it made a return for our shareholders.”

McAdams notes that notifying clients was hard, particularly because most were with the firm because they shared a world view and values.

As for life after the acquisition? McAdams and his wife have been traveling, enjoying hobbies and catching up on long neglected projects. “I’m probably at a stage where being on boards might make the best use of my experience, says McAdams. “I‘m not currently enthused about being another CEO, but I wouldn’t rule it out if something really disruptive came around.”

Perhaps there’s a firm out there in need of a name.