Sometimes we find puzzling things in our archives at the Miller Library, and they lead to fascinating stories. Here is one example.

Inside a folder on the subject of “Washington Park Arboretum founding” is a photocopy of a printed document from 1930 (which appears to be an internal document, not formally published), with no cover or title page. A typewritten 1962 paper by UW student Marjorie Clausing (“Our Arboretum: Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow”) refers to this as “Bulletin No. 1” of the Arboretum and Botanic Garden Society of the State of Washington—not to be confused with the “Arboretum Bulletin,” first published by the University of Washington in 1936.

The Arboretum and Botanic Garden Society, formed in early 1930, was a short-lived group, set up to help establish and maintain an Arboretum at Washington Park—a kind of precursor to the Arboretum Foundation. It seems the group only produced one of these bulletins before dissolving. The lengthy title of the document in our archive is “A history of Arboreta and Botanic Gardens, Tentative Plans for Washington Park Arboretum development, articles of incorporation, with a foreword by Sara Wrenn.”

What especially caught our attention was Sara Wrenn’s colorful writing style. She begins by describing the Washington Park of 1930, five years before the establishment of the Arboretum: “A pleasant, fruitful land, yet withal neglected, in watercourses, changed and dry, in wanton undergrowth and ragged trees.”

She then envisions the place 100 years in the future. Here is an excerpt:

“The years roll by. Times registers 2030 A.D. Gone are the unlovely places of yesterdays. Lagoons, bordered with lily and lotus blossom, with water plant of home and abroad, wind in and out where lush green willows dip their long tendrils delicately; where the brilliant foliage of all the maples mingle; where lilacs and bamboo reflect themselves; where cherry and plum tree, wild red currant and fragile huckleberry spread the waters with shattered rainbow hues. Lagoons where fish, even to the lordly silversides, disport themselves; where white swans float, the grey geese call, and ever and anon the wild ducks rise to wing.

“Trees, shrubs and flowers from all the temperate zone add their beauty to those with which Nature blessed the Pacific Northwest. The blue spruce of Colorado and the spruce of Norway fraternize with the majestic Douglas. Broad, grassy avenues lead through drooping hemlocks mingled with pines, the purple-berried juniper and the lace-mantled cedar, even to the cedars of ancient Lebanon.

“…On the open hillsides glow azaleas of every color, spilling their fragrance on the soft south winds.”

Not too far off the mark, really, when you consider the botanical riches growing in today’s Arboretum! Wrenn goes on to describe a great glass dome with a library, museums, herbaria, and conservatories—all on Foster Island—thereby envisioning a kind of hybrid between the Center for Urban Horticulture and the Amazon Spheres! This obviously was never created, but it does align with early plans for the north end of the Arboretum developed between 1932 and 1934 by Seattle Parks Department landscape architect Frederick Leissler, who went on to become the Arboretum’s assistant director from 1935 to 1940. (Leissler helped execute the Olmsted Brothers planting plan for the Arboretum, completed in 1936.)

We don’t know how much, if any, of if the 1930 vision of the Arboretum originated with Sara Wrenn, or if she was simply hired to put it all into memorable prose. We were perplexed, however, to find a version of Wrenn’s poetic writing in another document from that era, but without her name attached.

In these same archives is a bound pamphlet dated 1931 also titled “Bulletin No. 1” of the Arboretum and Botanic Garden Society. The foreword is nearly identical to the 1930 document, but its authorship is credited to Herbert H. Gowen (for whom the University of Washington’s Gowen Hall is named), and the vision of the future is adjusted forward in time by one year, to 2031.

In the Arboretum’s official historic review, published in 2003 as part of the Arboretum Master Plan (see http://depts.washington.edu/uwbg/docs/arbhistory.pdf), Gowen is credited with the authorship of this vision. But did the prominent professor do a few light edits and simply attach his name to it? Was the original author consulted?

It made us wonder: Who was Sara Wrenn? We did some digging around, and here’s what we were able to discover.

Crediting Sara Wrenn

Sara Blanche Wrenn was born in Oregon on April 24 either in 1873 or 1881 (census and passport records vary). Her jobs included railroad clerk, an Oregon Supreme Court stenographer, and an advocate of women’s suffrage. During World War 1, she spent time doing “war work in the industrial centers of the east” as a special agent of the investigation and inspection service of the Department of Labor. She traveled to Asia as a journalist between 1919 and 1922. An item in the society pages of The Morning Oregonian (June 8, 1922) announces her return from abroad:

“She passed 18 month in Pekin and a year and a half in Japan, Corea, and other countries. She was the first woman correspondent through the famine district. She went for the Philadelphia Ledger and visited many out-of-the-way places. Miss Wrenn will be in Portland for a few days and will pass the summer at Gearhart. She will do some writing while at the beach. She will be the guest of her sister, Miss E. E. Wrenn.”

In the 1920s, Wrenn ran a tea room called The Yellow Lantern Under the Hill in the Oregon seaside town of Gearhart. By 1930, she was working as a publicity writer for the Seattle Chamber of Commerce. She was well-known enough that the society gossip column of the “Town Crier,” a Seattle weekly publication, noted her heading back to work downtown from her lunch break uptown!

She corresponded with Edmond S. Meany while researching an article about pictographs in the Pacific Northwest around the same time that she wrote the preface for the Bulletin. She also published a travel article in the “Los Angeles Times” in June 19, 1931, “Vacation Land Invites Weary: Northwest Spreads Alluring Choice for Tourist.” The similarity of the prose to that in the Arboretum document is obvious: “The Evergreen Playground is the land of summer dreams come true. A region of jade-green waters, of mighty trees, lush greenery of fern and perennially verdant boscage.”

Wrenn may not have been a close associate of Herbert Gowen, but they ran in the same social circles: The December 5, 1931 holiday arts feature of the “Town Crier” includes contributions by both. Sara Wrenn’s piece is called “The City that Grew,” about “the most northern of America’s four guardians of the Pacific rim,” Seattle. In the essay, she uses the very same phrase from the “Bulletin No. 1” foreword to describe “the white eminence of Mount Rainier—The Mountain that was God.” Gowen’s piece is “A Christmas Message,” and it is suitably sermon-like. Gowen was head of the UW’s Oriental Art and Literature department, but he was also an Anglican rector.

Wrenn was active in the Seattle writing scene, and in 1933 was serving as corresponding secretary of the Seattle Penwomen’s League, a chapter of the League of American Penwomen. In the 1930s and 1940s she worked for the Federal Writers’ Project (created in 1935 as a branch of the Work Progress Administration), collecting oral histories in and around Portland on subjects such as early pioneer life and early horticultural history and lore.

We found no trace of her after the 1940s until her death in 1962. It is possible she spent her later years caring for her older sister Etta, with whom she lived in Seattle’s Queen Anne neighborhood and in various locations in Oregon over several decades.

We may never know if Wrenn was actively involved in planning and advocacy for the Arboretum. Likewise, we don’t know if she consented to have her writing presented with superficial changes under Herbert Gowen’s name. The value in delving into her past is to give credit where it is due.

[The article above was written by Rebecca Alexander with research contributions from Laura Blumhagen and Jessica Moskowitz. It appeared in the Winter 2020 issue of the Washington Park Arboretum Bulletin.]

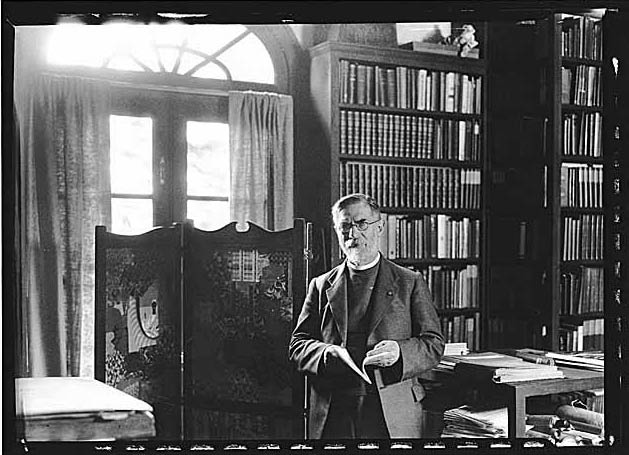

Reverend Herbert H, Gowen, Seattle, 1932 Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; All Rights Reserved, 1974.5923.42.1

Reverend Herbert H, Gowen, Seattle, 1932 Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; All Rights Reserved, 1974.5923.42.1

Below is an excerpt from the 1931 edition of the Arboretum and Botanic Garden Society of the State of Washington’s Bulletin No. 1, a brochure which included a foreword credited to the Reverend Herbert H. Gowen, D.D. Reverend Gowen, a passionate supporter of the Arboretum:

Sometimes the activity of the present may be stimulated by the projection of ourselves forward into a vision of the future. The following vision, however, placed just a century hence, need not be so long delayed. If we rise to our present opportunity, the present generation need not be denied the beauty and the usefulness of the Lake Washington Arboretum as here foreseen:

The years have rolled by. It is A. D. 2031. Gone are the untended and undeveloped places of yesterday, at least along the shores of Lake Washington. Bordered with lily and lotus blossoms, with water-plants native and foreign, the lagoons wind in and out where the lush green willows dip their long tresses delicately; where the brilliant foliage of maple lingers; where the lilacs and bamboos glass themselves; where wild cherry and plum, wild currant and huckleberry reflect themselves in the water like broken rainbows; where fish, even to the lordly silversides, disport themselves; where the white swans float, the gray goose calls, and ever and anon the wild ducks rise to wing.

From all over the temperate zone trees, flowers and shrubs have added their beauty to that of our native varieties. The blue spruce of Colorado and the spruce of Norway fraternize with our beloved Douglas fir. Grassy avenues lead through drooping hemlocks mingled with pines, the purple-berried juniper and the lacey-mantled cedar, even the cedars of distant Lebanon. Against the background of evergreens gleam the white star-blossoms of the dogwood and the creamy clusters of mountain ash or elder. Although more intimately withdrawn, the spreading, stately elm, the madrona, so showy of trunk and so glistening of foliage, the alder, the oak and the maple invite visitors to their friendly shade.

Through the boles of forest trees there drift the sunset tints of massed rhododendrons and the richness of the mountain laurel. On open hillsides burn the azaleas of every hue, their fragrance spilled as it were upon the soft south winds. There are also shaded retreats of coolness, where streamlets sing over mossy boulders; shaded retreats revealing to the seeker mazes of delicate ferns, shy wind-flowers, trilliums and erythroniums, and that gift of the fairies, the calypso and its kin. Through the vales and little dells, and up the hillsides, wind beautiful walks, now crossing a rustic bridge, now passing beneath a graceful arch, now skirting the broad waterways and bubbling brooks. Alluring ways lead to sunken gardens, where beauty and sweetness are subtly distilled – where the gentian drops its veil of tangled blue and alpine shrubs from every land lend a sturdy background to anemones, muscari, campanulas, primulas, saxifrages, veronicas, and all the rest.

Only a short distance away is the physic garden, where grow the healing plants of every continent. Here also is the Pharmaceutical College, which, by reason of worldwide research, has served its part in alleviating and eliminating human ills and the ills to which other forms of life arc heir.

Need we speak of the roses – countless roses, growing in dignified formality of tree or bush, climbing the pillared pergolas, sending forth their confused and pervading odors. Arbor and trellis trail with creepers, familiar and strange alike – starry clematis, wisteria with pendulous plumes of white and lavender, and the homelike honeysuckle. On gently sloping terraces fruit trees and vines will bend beneath their luscious burden. The whole place is filled with the song of birds and the humming of industrious bees. Splendid of raiment, the pheasant-cock struts with his harem, coveys of quail make their leisurely way from copse to copse, bright eyes – all unafraid – peep out from covert and tree-top. In peace and security man’s friends of air and field and wood and water dwell here as in a sanctuary.

Crowning the mild eminence once known as Foster Island an architectural group dominates the scene. The great glass dome is that of the Administration Building. Close by are the Library, the Museum, the Herbarium, and the great conservatories for the rarer plants – all alike bowered in shrubbery and flowering vine. Along with ample provision for flower shows and botanical exhibitions are committee rooms and, of course, the auditorium. There are also buildings devoted exclusively to the study and development of new forms of flora. That the life of man may be enriched there is here the fusion of all that is best in science and industry as well as in art.

Meanwhile, the great University remains, with its witness to the pioneer days of the Greater Seattle. The ivy-covered buildings have increased in number, while some have grown almost venerable, for the sake of the multitudes who seek knowledge within their halls. The hum of the many-towered city is distinctly heard, linking man’s industrial activity with the beauties of Nature and the fruit of his highest culture. The waters stretch like a gleaming girdle towards the blue-green of the enveloping forest. Beyond all are the mountains, with their brooding sentinels of eternal snow. And above all our sublimest Rainier – “the Mountain that was God” – looks down upon a dream come true.