The nautilus shell is a familiar shape, reminiscent of the golden ratio or the decorative soaps in your grandmother’s kitschy beach-themed pastel bathroom. Nautiluses – cephalopod mollusks, relatives of squids and octopuses – are as enigmatic and striking as their famous outerwear.

Nautiluses’ unique natural history and ancient body plan set them apart from their cephalopod brethren. They are the only cephalopod lineage to keep its external shell and are thought to never stray far from the sea floor. They are limited on the shallow end by their low tolerance for the warm surface waters of the Indo-Pacific, where they exclusively reside, and on the deep end by a fatal-shell-implosion depth (which is as sad as it sounds) of about 800 m. In contrast to squid, they are lousy swimmers. The octopus has amazing eyesight – nautilus, not so much. Despite these potential evolutionary “shortcomings,” nautiluses have been around for a LONG time; modern nautilus appear to have changed very little from their Mesozoic ancestors (over tens of millions of years), designating them as “living fossils.”

Humans fish for nautilus throughout the Indo-Pacific, most heavily in the Philippines. No one is making calamari out of these cephalopods, however – nautiluses are collected solely for their beautifully spiraled shells. From Etsy to eBay to local gift shops, stores sell nautilus shells for decoration, and the United States is the primary market. There’s a big problem with this fishery: nautilus have long life cycles – slow to mature to reproductive age (15 years!), slow to reproduce (only 2-10 eggs per year!), and live for decades (but no one knows how long!). Low fecundity meets unregulated fishing – this probably will not end well for our intriguing, many-tentacled friends.

Regulating the nautilus fishery is a logical next-step to protect these charismatic creatures. Encouragingly, the upcoming CITES (Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) meeting will discuss nautiloids (the group of living nautiluses, containing the genera Nautilus and Allonautilus). This is great news! The CITES is an international treaty that accords protections to plants and animals that are under threat of over-harvesting. Our research group and others agree that nautiloids certainly qualify for protection. To help CITES figure out how best to protect the nautilus, there is a big logistical question – how many nautilus species are we protecting, anyway? Genetics tools are shaking up our understanding of taxonomy across the tree of life, and the nautiloid lineage is no different.

| Nautilus have pinhole eyes, striped shells, and tentacles for days. Photo: Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute |

The family Nautilidae has a historically disputed number of species, from only two to over a dozen. While scientists have described many species based on shell differences, some researchers are wary of these morphological taxonomies. Remember how nautiluses are lousy swimmers with a restricted depth and temperature range? If nautiluses are found on islands and land masses hundreds or thousands of kilometers apart, do each of these locations have separate non-interbreeding populations? Separate species? Something in-between?

To genetically assess how many Nautilus species there might be, we sampled tissues of hundreds of individuals from across the known range of the Nautilus: Fiji, American Samoa, Philippines, Vanuatu, and Australia. Don’t worry, our sampling method was non-lethal (we snipped just one of the nautilus’s 90+ tentacles). We then sequenced two mitochondrial genes for each individual. Using phylogenetics and population statistics, we analyzed our sequences (and others published previously) to examine how many Nautilus species there might be and how genetically distinct the different populations are.

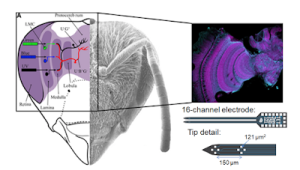

| Figure from Vandepas et al. 2016 |

We found that there are likely two species in the genus Nautilus: Nautilus macromphalus and Nautilus pompilius. Unexpectedly, we also found that the individuals on different land masses didn’t seem to be completely genetically isolated, even though they are separated by vast expanses of ocean. We propose that there is a large Nautilus pompilius metapopulation (many interbreeding groups of populations). A really interesting thing about this finding is that this conclusion is contrary to the nautilus’ seemingly isolated lifestyle. If nautilus populations are located hundreds of kilometers apart and nautilus don’t get around very well, as far as we know, how can populations be so closely related? We don’t have an answer for this yet, though some interesting ideas have been informally thrown out there – are baby nautilus more mobile than their parents, hitching rides on deep-water currents like the surfing turtles in “Finding Nemo”?

As far as protecting these amazing animals, my coauthors and I argue that due to their slow life cycle and longevity, nautiluses should be harvested minimally or not at all. Healthy populations may potentially replenish others that have crashed due to fishing, as long as they are protected. The proposed fishing regulations could go a long way in ensuring that these long-lived, funky cephalopods stick around to fascinate future generations and help maintain the amazing biodiversity that lives in our deep oceans.

————–

Vandepas et al. 2016 is available here (open access): http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/ece3.2248/full