Back to Cities and Architecture

BALKH AND MAZAR-e-SHARIF

by

Frank Harold

(Click map to enlargen)

Click on thumbnails to enlarge them

Balkh was old long before Alexander’s raid, and its history of 2500 years records more than a score of conquerors. The Arabs, impressed by Balkh’s wealth and antiquity, called it Umm-al-belad, the mother of cities. When the Silk Road was the chief artery of commerce between East and West, Balkh was second to none. But then came Ghengis Khan, and wreaked upon it the utter devastation that has made the Mongols’ name a byword for barbarism. Balkh never fully recovered, and eventually faded into a village; the seat of government shifted to scruffy but vigorous Mazar-e-Sharif. What the visitor comes to see in Balkh is chiefly the melting walls of the old city, enclosing a vast field of rubble and wreckage; it is a place of memories rather than monuments. But for those who savor the melancholy pleasure of ruins, there is no more evocative site between Xian and Trebizond.

Why here, on this drab plain between the Hindu Kush mountains and the river Amu Darya (Oxus) ? At one level, geography holds the key. Balkh sits on an alluvial fan built up by the Balkab river, well suited to irrigation. The region called Bactria in ancient times was renowned for its grapes, oranges, water lilies and later sugar cane, and an excellent breed of camels too; to this day, some of the world’s most luscious melons come from nearby Kunduz. Most significantly, several natural trade routes intersect at Balkh. From there, caravans could follow the well-watered foot of the mountains westward towards Herat and Iran, or across the Oxus to Samarkand and China (see map). The valley of the Balkab still gives passage to Bamiyan and thence to Kabul; of all the routes across the Hindu Kush, this is the most westerly and the easiest. But geography is at most opportunity, not destiny; and the greatness of Balkh owes even more to those distinctive people who promoted craftsmanship and trade, created cities and wrote poetry all across the Iranian world. On the down side, Balkh was usually rich rather than powerful, and became the envy and the prize of more warlike neighbors.

Always a place of importance, Bactria and its capital city figure prominently in the annals of historians and travelers. It first appears on a list of the conquests of Darius, who incorporated it into the Achaemenid empire. Zoroaster taught here, perhaps in the 6th century B.C.E., and the Zoroastrian faith became the state religion of of the Achaemenids and later of the Sassanians. Alexander took Bactria in 329 B.C.E., and made it his base for conquest and amalgamation of the Greek and Iranian civilizations. That vision survived for another two centuries in the small Graeco-Bactrian kingdoms that thrived and quarrelled on both sides of the Hindu Kush; they wrote no history, but minted the most gorgeous silver coins of the ancient world.

Bactria reappears with its annexation by the Kushans (129 B.C.E.), whose large and powerful empire stretched from Central Asia deep into India. This was a fortunate era, when the lands through which the caravan routes passed were divided among a few stable states which submerged their differences in the interests of trade; and Balkh flourished at the crossroads as a depot and trans-shipment point for the world’s luxuries. “ From the Roman Empire the caravans brought gold and silver vessels and wine; fom Central Asia and China rubies, furs, aromatic gums, drugs, raw silk and embroidered silks; from India spices, cosmetics, ivory and precious gems of infinite variety” (Dupree, p 71). With the merchants came monks preaching the new religion of Buddhism, and Balkh became a center of worship and learning, famous for its temples and monasteries.

By the time the Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (formerly spelled Hsuan Tsang) passed through Balkh (630 C.E.) on his way to the fountainhead of Buddhism in India, the city had become part of the Sassanian empire. The bazaars were still humming with trade, the countryside fertile and the great temples impressed him with their magnificence. But Xuanzang noted laxness among the monks, and the rise of Zoroastrianism. There was strife with the Turki nomads across the Oxus, and the Arab incursions were just fifteen years ahead.

The times that followed were turbulent ones in Central Asia. Balkh changed hands repeatedly among Arab, Persian and Turki rulers, and was sacked more than once, yet it continued to flourish. The Arab geographers Yaqubi and Moqaddasi (9th and 10th centuries) depict Balkh as it was under Samanid rule, whe Bukhara was the center of power. A large and prosperous city of mud brick some three square miles in area, it held perhaps 200,000 persons. It was surrounded by mud-brick walls pierced by seven gates. A splendid Friday Mosque occupied the center, and many more mosques were scattered among the dwellings. The fire temple in the suburbs, which Xuanzang had admired when it was a Buddhist monastery, was still noteworthy. The city was home, not only to Persians and Turks but also to communities of Jews and Indian traders. It nourished poets and scholars, lawyers and even geographers and astronomers. But peace was a sometime thing; even when Balkh came under Seljuk rule for over a century, the nomads were never far away.

Catastrophe struck in 1220, when Ghengis Khan chose to make an example of Balkh, perhaps as punishment for an uprising. One hundred thousand Mongol horsemen embarked on an orgy of slaughter and destruction that left nothing standing; a few weeks later they returned to pick off the survivors of the carnage. Balkh remained in ruins for a century, and ws so described by Marco Polo (1275) and by Ibn Batuta (1333); and yet revival must have been under way, for Timur (Tamerlane) chose Balkh to proclaim his accession to the throne (1359). Timur and his successors favored Balkh; they restored the walls and endowed the city with quite splendid buildings, some of which survive.

Balkh remained worth fighting over, by Uzbeks, Safavids, Mughals and eventually the rising power of Afghanistan under the Durrani Shahs. But the city slowly declined as its surroundings grew swampy and malarial, and cholera struck again and again. By the beginning of the 20th century the population was down to 500 households, and the administrative center of Afghan Turkestan had migrated (1866) to nearby Mazar-e-Sharif. A new chapter had begun, the one that we are still living in.

Of all this eventful history, little enough remains on the ground (see the images). One arrives (1970) in the center of an agricultural market town, neatly planted with trees and grass, that show off two Timurid edifices. One is the mausoleum of Khwaja Abu Nasr Parsa, erected in1462/63 in honor of a distinguished theologian; it is considered one of the finest examples of late Timurid architecture and often features on tourist posters. The shrine consists of a tall octagonal brick chamber surmounted by a fluted dome; entry is through a high portal flanked by a pair of spiral columns. The entire exterior is clad in brilliant blue tile mosaic, much of which has been slowly peeling off the walls. The interior is cool and austere, decorated with stucco honeycomb and painted floral designs. Across the park stands a tall gateway with some decorative tilework; this is all that remains of a madrassah built in the 17th century in Timurid style.

Of all this eventful history, little enough remains on the ground (see the images). One arrives (1970) in the center of an agricultural market town, neatly planted with trees and grass, that show off two Timurid edifices. One is the mausoleum of Khwaja Abu Nasr Parsa, erected in1462/63 in honor of a distinguished theologian; it is considered one of the finest examples of late Timurid architecture and often features on tourist posters. The shrine consists of a tall octagonal brick chamber surmounted by a fluted dome; entry is through a high portal flanked by a pair of spiral columns. The entire exterior is clad in brilliant blue tile mosaic, much of which has been slowly peeling off the walls. The interior is cool and austere, decorated with stucco honeycomb and painted floral designs. Across the park stands a tall gateway with some decorative tilework; this is all that remains of a madrassah built in the 17th century in Timurid style.

The earlier monuments take some searching. A couple of nondescript mounds probably mark the site of that Buddhist/Zoroastrian temple that Xuanzang described as being “lustrous with precious gems”. A small brick mosque, decorated with carved stucco survives from early Islamic times, but we failed to find it. What we had come to see is the walls, battered and weather-beaten but still sixty feet high in places, that enclose the Bala Hissar, the High Fort. The ramparts were built in Timurid times (14/15th centuries) upon foundations that likely go back to the Kushans and possibly further. They enclose a roughly circular field almost a mile across, that probably corresponds to the central city of medieval Balkh. Now there is only dry scrub and low mounds of debris; here and there potsherds and broken bricks seem to call for attention. There is nothing much to see; but I have never forgotten what it felt like, up there on those worn stumps of wall, gazing out over nothingness.

The earlier monuments take some searching. A couple of nondescript mounds probably mark the site of that Buddhist/Zoroastrian temple that Xuanzang described as being “lustrous with precious gems”. A small brick mosque, decorated with carved stucco survives from early Islamic times, but we failed to find it. What we had come to see is the walls, battered and weather-beaten but still sixty feet high in places, that enclose the Bala Hissar, the High Fort. The ramparts were built in Timurid times (14/15th centuries) upon foundations that likely go back to the Kushans and possibly further. They enclose a roughly circular field almost a mile across, that probably corresponds to the central city of medieval Balkh. Now there is only dry scrub and low mounds of debris; here and there potsherds and broken bricks seem to call for attention. There is nothing much to see; but I have never forgotten what it felt like, up there on those worn stumps of wall, gazing out over nothingness.

We stayed in Mazar-e-Sharif (“Tomb of the Exalted”), which boasted a decent hotel and even occasional electricity. There is nothing ancient or traditional about Mazar, which only rose to prominence in the 19th century. We found it a bustling “third-world-modern” town of straight wide streets, motor traffic, government offices and shops. Uzbeks, Tadjiks, Hazara and Pashtuns meet and chaffer in the seat of power, which is also a center for trade in Karakol lambskins and carpets. More recently, Mazar has all too often been in the News, and has seen much fighting during the long years of conflict between Russians and Mujaheddin, Taliban and the Northern Alliance, and lately Americans too. But the great shrine of the Sharif Ali, which lent the city its name, has survived the turmoil (see images).

Hazrat (The Noble) Ali is one of the central figures of Shia Islam, and almost as much revered as the Prophet Muhammad himself. Ali ibn Abu Talib was Muhammad’s cousin and son-in -law, and eventually became the fourth Caliph. But his reign was marred by discord; the Caliph was assassinated in 658 C.E., and according to orthodox tradition was buried in Najaf, Iraq. Afghans believe otherwise: the body of the slain Caliph, tied onto a camel’s back, was carried out to Turkestan and buried in a secret location. Five hundred years later, thanks to dreams and visions, the grave came to light and a shrine was built over it. Ghengis Khan levelled it, but Ali’s sepulchre was rediscovered during the reign of Husain Baikara, the last Timurid Sultan of Herat, who erected a grand mausoleum on the site (1481 C.E.). This is the building, many times restored and re-dec0rated, that one sees today (see images). With its two domes, impressive courtyard and portals, excellent blue tilework and a flock of white pigeons, the shrine of Hazrat Ali is one of the most spectacular buildings in Afghanistan. Pilgrims flock to the tomb, which has a reputation for miraculous cures; and many thousands come here each spring to celebrate Naoruz, the Persian New Year.

Hazrat (The Noble) Ali is one of the central figures of Shia Islam, and almost as much revered as the Prophet Muhammad himself. Ali ibn Abu Talib was Muhammad’s cousin and son-in -law, and eventually became the fourth Caliph. But his reign was marred by discord; the Caliph was assassinated in 658 C.E., and according to orthodox tradition was buried in Najaf, Iraq. Afghans believe otherwise: the body of the slain Caliph, tied onto a camel’s back, was carried out to Turkestan and buried in a secret location. Five hundred years later, thanks to dreams and visions, the grave came to light and a shrine was built over it. Ghengis Khan levelled it, but Ali’s sepulchre was rediscovered during the reign of Husain Baikara, the last Timurid Sultan of Herat, who erected a grand mausoleum on the site (1481 C.E.). This is the building, many times restored and re-dec0rated, that one sees today (see images). With its two domes, impressive courtyard and portals, excellent blue tilework and a flock of white pigeons, the shrine of Hazrat Ali is one of the most spectacular buildings in Afghanistan. Pilgrims flock to the tomb, which has a reputation for miraculous cures; and many thousands come here each spring to celebrate Naoruz, the Persian New Year.

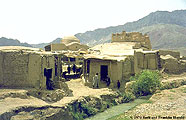

Neither Balkh nor Mazar look anything like a caravan city of the middle ages, but nearby Tashkurgan does (or did in 1970; see images). A ruined mud-brick castle looms over the town; it is only a couple of centuries old, but the weathered walls give it an antique air. The bazaar was fascinating, a place of traditional crafts, small open-fronted shops and inviting chai-khanas (tea houses). You sit on a takht, a throne, by the side of the street, sipping your tea while puffing on a hookah, and watch the parade of Central Asia pass by. That was in a time of peace, which seemed like innocence; I wonder how Tashkurgan has fared.

Neither Balkh nor Mazar look anything like a caravan city of the middle ages, but nearby Tashkurgan does (or did in 1970; see images). A ruined mud-brick castle looms over the town; it is only a couple of centuries old, but the weathered walls give it an antique air. The bazaar was fascinating, a place of traditional crafts, small open-fronted shops and inviting chai-khanas (tea houses). You sit on a takht, a throne, by the side of the street, sipping your tea while puffing on a hookah, and watch the parade of Central Asia pass by. That was in a time of peace, which seemed like innocence; I wonder how Tashkurgan has fared.

Sources

The history of Balkh, and the reports of ancient travelers, are covered in some detail by G. Le Strange, The Lands of the Eastern Caliphate (1905; re-published by Al- Biruni, Lahore, Pakistan); and in articles on Bactria and Balkh by F. Grenet in Vol. 3 of the Encyclopedia Iranica (E. Yarshater, ed; Routledge and Kegan Paul, London). A very readable account of the land, its past and its present will be found in The Road to Balkh, by Nancy Hatch Dupree (The Afghan Tourist Organization, Kabul, 1967); unfortunately, this little gem is now a collectors’ item. The most celebrated traveler’s tale is surely The Road to Oxiana, by Robert Byron (1937; reprinted by Jonathan Cape, London, no date). Discerning readers will also enjoy The Light Garden of the Angel King, by Peter Levi (Collins, 1972).

Back to Top

© 2006 Frank Harold.

Silk Road Seattle is a project of the Walter Chapin Simpson

Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington. Additional funding has been provided by the

Silkroad Foundation (Saratoga, California).