Back to Traditional Culture

Food

Introduction:

For many people, their first exposure to other cultures comes through food. What people eat in

traditional cultures is determined both by natural conditions and the local economy and also by

ritual and belief--often religious views regulate what may and may not be consumed even if it

could be produced. Food culture goes beyond simply what is consumed; it generally involves

particular rituals of serving, hospitality, and celebration. This page will explore food

culture primarily amongst the Central Asian nomads. We will illustrate some of the stages of

food production, and discuss as well the role of food in the rituals of daily life.

The diet of nomads was very much dependent on their livestock and consisted primarily of milk

products and meat. Any of the traditional nomadic animals--sheep, goats, yaks, and camel--would

be milked and the milk used to make butter, yogurt (ayran) and qurut. Qurut is the dried

round-shaped sour curds which could be consumed at times when when fresh milk products were

not available, during winter, or at other times when food shortages resulted from droughts and

severe weather conditions. Qurut could also be taken as "trail food" by those who might be away

from the nomadic camp or on a military campaign. Qurut is crushed and boiled in water to make a

healthy meal rich in calories and vitamins.

Another important food product was fermented mare’s milk, the sour drink called koumiss which

still has not lost its popularity among Central Asians. Koumiss is to the nomad as wine is to

the French. Although koumiss is fermented, the Central Asian nomads do not consider koumiss as

an alcoholic beverage, but rather a wholesome drink. For a sixteenth-century account extolling

the medicinal properties of koumiss, click here.

Even babies as young as one year old can drink

it. In addition to being just a drink, koumiss was also used for ritual purposes: before

leaving for battles soldiers and their horses were blessed with koumiss to wish them a safe

return. The first Mughal emperor, Babur, provides a description of a

koumiss ceremony in

advance of a military campaign.

Meat, most commonly mutton or horse meat, was boiled in a big cauldron. Usually only well-fed,

fat sheep or horses were slaughtered (never skinny ones), for the nomads had to consume fat to

survive the cold in the mountains. The men had the responsibility for slaughtering the animals

and had to employ a special technique. It is still important for Central Asians to divide the

meat according to the muscle structure. Each part of the animal, including the head, will be

boiled carefully and served in large pieces to guests in ritual order. Elderly people today are

upset if they see that the meat was not separated and served properly. [For video footage of

the ceremonial serving of a sheep's head in a nomadic yurt, see the Silk Road series,

Film 11,

which also shows milking a mare and preparing of qurut.]

Our written sources about nomadic life in Inner Asia document how even two millennia ago the

nomadic diet consisted of more than just the products of the flocks. Many nomads also consumed

grain products, especially in circumstances where there was regular interaction with sedentary

agriculturalists, although to a considerable degree the amount of grain in the diet seems to

have depended on a family's wealth. The Han Chinese chronicles recount the sending of

substantial amounts of grain to the Xiongnu (Huns) who lived beyond the Great Wall. Envoys to

the Mongols in the thirteenth century noted that at least the wealthy had supplies of millet

and flour. In the early 1920's the British Consul in Kashgar, C. P. Skrine, noted regular trade

in grain taken to the nomads in the Tien Shan and the consumption of a soup of flour and milk

by the Kyrgyz, a tradition which continues today. The visitor to Kyrgyz mountain camps today

sees them baking bread and consuming grain products (for example, pasta) which are carried up

to the summer camps.

Among the historic varieties of nomadism were ones where grain might be sown near the winter camp to ripen while the family was away in the summer pastures. Alternatively, especially where nomads increasingly become sedentarized, families in the lower mountain valleys might combine herding with the growing of crops. Here we can see from a distance such a camp in the Lyaylak Valley of the Pamir-Alai in late summer when the harvest was underway. The family was growing corn and wheat; they herded goats and raised turkeys. A few additional pictures here illustrate stages of the grain harvest. The sheaves are piled up and a team of animals walked over them to break up the stalks and free the kernels from their husks (here we have one example of a traditional threshing floor from the same camp in the Lyaylak and another taken at a village on the way down from the Torugart Pass in Western Xinjiang). Lastly, we see the winnowing of the grain to separate the kernels from the chaff. The example is from the Tajik village of Dabdar on the high plateau between Mustagh Ata and the Khunjerab Pass in Xinjiang. The threshing floors are simply beaten earth; so the final stages in processing the grain will involve sifting it and then, before grinding flour, washing it.

Some visual impressions.

(The pictures and annotations which follow illustrate details of food culture.)

Here we have two views of milking a mare. In the first (taken in the Ak-Suu, Aksï region,

southern Kyrgyzstan) Elmira Köçümkulkïzï is doing the milking while her maternal uncle holds the horse;

the second is taken at Erdeni-tsu in the Orhon River region of Mongolia. Mares are milked two

or three times a day depending how fast their udders fill with milk. Traditionally, the milking

of mares was done by men only. However, it was not a strict rule, for, women also can milk if

men are not around. As you can see, milking a mare is a bit different from milking a cow. The

left hand holds the bucket and at the same time milks, the right hand goes between the two back

legs and milks. The long stick which Elmira's uncle is holding on the mare’s neck is called

ukuruk among all the Central Asian nomads. Ukuruk is used to catch wild horses and train them

for riding. Many mares stay calm during milking if one puts the ukuruk on their neck. During

the day time, while their mothers go to graze, the foals are tied to a long rope tied closer to

the ground, so that they do not follow their mothers and suck their milk. Before milking a

mare, it is necessary to let her foal suck first to bring the milk flow to the udder. At the

end, people leave some milk for the foal too.

At the higher altitudes in Inner Asia, yaks may be more important than other animals. To some extent they are found in the mountains of southern Kyrgyzstan, although there they would not be an important source of milk. They are more common amongst the Kyrgyz living in the high mountains south of Kashgar in Xinjiang. In Tibet, yaks are the mainstay of the traditional nomadic economy. The picture here shows milking a yak in the village of Subax next to Lake Karakul, Eastern Pamirs, Xinjiang. As in the case with mares, it is necessary to allow the baby yak to suckle first to start the milk flowing in order then that the mother be milked.

In areas where camel herding is the dominant economic activity of the nomads, camel milk may be a principal source of food. The Silk Road video series has footage of camels being milked. When in Mongolia in 1979, Prof. Waugh was offered camel-milk yogurt (in a pot on the stove in this family's yurt), and the camel-milk cheese laid out here on a table to cure. The cheese had about the consistency and taste of Greek feta cheese (made from goats' milk). Presumably if this cheese were dried in the sun, it would become qurut. A drink called shubat is prepared from camels' milk.

Separating the cream, Kara-Suu Valley, Pamir-Alai, Kyrgyzstan. Today, almost all the people who extract cream from milk use modern separators. Raw milk is first heated in a cauldron, then poured into the bowl of the separator. The cream is extracted into a separate container, while the skim milk, which is called kök süt (blue milk), is used for making bread or sometimes may be added to dog food. Although some people make qurut from the skim milk, it does not taste as good as that made from whole milk. Before the advent of mechanical cream separators, people just boiled the milk and then let it cool. When the milk had cooled they just scooped out the thick layer of cream on the surface. This traditional way is still practiced among some people who do not have a separator.

Here is another view of a woman separating cream from milk, in this case inside of her mountain

hut. When he saw how the photographer seemed to be interested only in what she was doing, her

young husband just had to get into the picture to show off what was important to him, his boom

box. That and his Adidas-imitation track suit give some idea of the degree to which the

traditional culture in the mountains of Southern Kyrgyzstan has been penetrated by the "modern

world."

This picture raises the question of what the respective roles of men and women are in the

pastoral economy. Usually, milking of a mare is done by men, whereas milking of a cow is done

by women. Most of the work associated with the processing of milk and making of milk products

is left for women. Cooking, baking bread, laundry, and making felt are all done by women. Men

usually give help in making felts for it requires strong arms to soften the wool with smooth

sticks and then press the rolled felt with forearms. Men take care of cattle and sheep and make

sure that all the cattle come home safely in the evening. They count their sheep every evening

after they come back from grazing to make sure that they are not missing or eaten by wolves;

men also wash sheep and sheer their wool with a traditional iron scissor called juushang.

If they have many sheep, they usually use modern electric clippers.

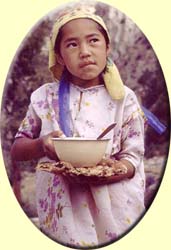

Girl stirring milk in a qazan (a large cauldron or wok), Ak-Suu Valley, Pamir-Alai, Kyrgyzstan. The girl is wearing a scarf, which is common for Kyrgyz living in the mountains as well as in some traditional Kyrgyz villages influenced by Uzbek or Tajik Islamic culture. The tradition today is that only married women, not girls as young as the one here, wear a scarf in Central Asia. However, in this case, the girl wears her scarf for the practical purpose of keeping her hair from falling into the milk she is stirring while it heats in the qazan.

Here we see a detail from the background of the previous picture--sacks of yogurt draining. The number and the size of these sacks tell us that this family owns several milking cows. Herding cows in at least the lower mountain valleys of Kyrgyzstan is now quite common, and they serve as the primary source of milk. Usually only those people who have more than three cows take them to the summer pasture to make butter and qurut. After the milk is boiled, as shown in the previous picture, it is poured in a big container in which it cools until it is warm. Then a certain amount of yogurt is added into it and covered with layers of blankets to sit overnight, after which the thickened yogurt is poured into such bags to drain. It usually takes two or three days to drain. One needs to guard these bags from dogs and calves, because they like to lick the sacks from outside.

Here is another view of processing of milk products, in this case among the Kyrgyz in Eastern Pamir, Xinjiang. Here too the milk is being heated in a qazan. The woman was mixing (perhaps preparing the qurut) in the wooden bowl and insisted on wiping off her arms and standing to pose formally rather than be photographed at work. In the background, as is typical in this region, the draining bags are suspended from a wooden platform, on top of which qurut was drying. This was an area where the families had a few cows and a large herd of yaks.

Back at the earlier camp in the Ak-Suu Valley, Pamir-Alai, a woman is churning butter. Behind her qurut is drying in the sun on the reed mat atop a platform. The drained yogurt, called süzmö, is used to make make qurut, dried sour curds. First, salt is added into süzmö and mixed thoroughly by hand. If there is a lot süzmö as in the two big bags shown above, it requires many hands to make qurut. Qurut comes in various shapes and sizes: some make it small and round to fit one’s mouth, some make it in an elongated form to hold and suck. It is necessary to keep an eye on drying qurut to prevent birds from stealing it. The qurut dries in three or four days and then is ready to bag. As the second picture shows, the qurut may simply be laid out on a mat or plastic on the ground to dry. As a rain shower came in this family hastily covered it with plastic sheeting.

This view is in the famous market in Samarkand next to the Bibi Khanum mosque. Among the man's

wares is qurut. Qurut can be found in markets of Central Asia sold together with other dried

food products such as fruits and nuts. The merchant here is an Uzbek; it is also common among

the Uzbeks to make qurut. However, its taste is generally not as good as that produced by

nomadic Kyrgyz or Kazakhs, because Uzbeks, who only have one or two cows, make it from non-fat

milk. Moreover, they usually add flour into the thickened yogurt to get more qurut, in the

process destroying its taste. In the past, including the Soviet period, the Kyrgyz and Kazakhs,

both nomadic and sedentary, did not themselves engage in selling and buying food products such

as qurut in markets. However, they made qurut in large quantities for themselves, for their

friends and relatives. It is also common to send qurut to one’s student children in cities.

One of Prof. Waugh's former professors recalls how eagerly his roommate from Central Asia, who

was then studying in Leningrad, opened a package of qurut from home--it was a real treat for

the homesick.

If the Kyrgyz would sell qurut, they did so in bulk and at relatively cheap prices to Uzbek

merchants. In the past, sitting and selling things at a market was considered a disgrace for

the nomads, since such occupations were always associated with "Sarts," town merchants. Today,

however, the new market economy is changing that traditional "nomadic" attitude of the Kazakhs

and Kyrgyz, who now are selling all kinds of goods and food, including qurut, at local

markets.

Here we can see some of the "kitchen equipment" of a typical herder's hut in the Ak-Suu Valley, Pamir-Alai. The processed milk is cooling in large aluminum cans, which are called fliyaga in Russian and can be found at almost every household in Central Asia. They are very good for storing water, milk or cooking oil. People use them in the mountains a lot for bringing water from a distance. Because they have a cover with a secure lock, water or milk does not spill when being carried on a horse or donkey. The iron qazan, cauldron, is also owned by every family in Central Asia. Families have several qazans in various sizes. The largest ones are used for making food such as rice pilaf and for boiling the meat of large animals such as horses or cows for large gatherings. The average size qazan like the one in this picture is used for baking bread or other day-to-day cooking.

Of course, aluminum cans were not always around in Central Asia, although some of the nomads (notably the Kyrgyz) historically were known for their metal-working ability, and the traditional trade with sedentary centers often included the importation of metal objects. Here we can see how even today, the natural products of the animals have not been replaced by modern conveniences. Central Asian nomads made very good use of their cattle. Not only did they eat cooked intestines of domesticated animals such as horse, sheep, goats, and cows, but they also used some inner organs, such as the stomach, as a storage bag. A sheep’s or goat’s dried stomach was usually used for storing butter. After a sheep is slaughtered, its stomach is carefully removed and cleaned well. It is processed while it is still wet and then hung to dry, as is the one shown hanging from the frame for a tent in the Uryam Valley of the Pamir-Alai in southern Kyrgyzstan.

In this hut interior in the Kara-Suu Valley, Pamir-Alai, we can see an empty animal’s stomach, qarïn, hanging from a beam and ready to be stuffed with butter. Storing butter in a dried animal stomach is believed to be an old practice in Central Asia. This smart invention was probably necessary for nomads who did not have refrigerators. Butter in a stomach can be stored more than a year without spoiling. People open it for special occasions or for special guests, for it tastes much better than regular unstored butter. In the second picture taken in the same home, Jamila shows a qarïn which has been filled with butter. Kerosene lamps, like the one hanging from the ceiling of this hut, are also commonly used by people living in the mountains where there is no electricity. The Kyrgyz call this kind of lamp tash çïraq (stone lamp), because it has a harder glass than regular lamps.

In her "pantry," one corner of a large herder hut in the Kara-Suu Valley, Pamir-Alai, the woman is turning the qazan over the hearth to bake bread. It looks as though she is also preparing a meal from a store-bought pasta. Today, the diet of nomads commonly includes modern manufactured foods such as noodles, spaghetti, and rice sold in local markets.

In the second picture, the bread is baking in the qazan. People bake bread in various ways in Central Asia. Semi-nomadic Kyrgyz, who live in yurts in the mountains, bake bread in a qazan. Baking bread in a qazan is more common among the people living in southern Kyrgyzstan than in the north. Northern Kyrgyz in rural areas bake bread called kömöç (from köm- "to bury") directly in the embers from a fire. The qazan bread is much flatter than kömöç bread. One needs to have a special firewood to bake bread in a qazan: usually, small firewood is used, because it burns well and leaves more embers than dung or any other firewood. The empty qazan is turned over the hearth with the piled embers in order to heat it so that the dough can stick well to the inner surface. An average size qazan such as this one can hold four or five flat breads.

In the Ferghana Valley, which also includes the southern part of Kyrgyzstan, people who live in permanent houses use clay ovens, tandoors. Just as in the qazan, the uncooked bread dough cooks while stuck to the wall of the hot oven. The camp shown here on the way from Osh city into the mountains is unusual in having a tandoor. To the left of the yurt a woman is standing in front of an outdoor clay oven, even though normally such oven would be used only by sedentary people in Central Asia. It is not easy to bring the ready-made oven to the mountains on horseback or camelback. Since this camp is right next to the road not far from Osh, probably the oven was brought from the winter home in the city by truck. The second photo shows a closeup of such a clay oven in an Uzbek home in Shahri Sabz. In places such as this where cotton is grown dried cotton stalks are used for fuel, because they leave a lot of embers after burning.

Here the freshly baked bread from the qazan in the hut shown above has been laid out to cool. People usually place the baked bread upside down when cooling it. In any other situations bread is always placed with its surface up. Everybody in Central Asia knows that it is a bad omen to put bread upside down. If one sees a whole round of bread or even a piece of it placed upside down, one immediately turns it over. This family is quite well supplied with food. These bags are likely to contain flour, rice, manufactured noodles, and maybe wool and grain. The object in front of the piled up blankets and pillows is a cradle with its covering.

The Kyrgyz woman in this yurt near Lake Song-Köl in northern Kyrgyzstan is offering food for her guests. There are two kinds of bread on the table, one is qazan bread and the other one is fried bread called boorsoq. Boorsoq (in Kyrgyz; baursaq in Kazakh) is very popular in Central Asia, especially among the Kazakhs and Kyrgyz. The dough is made of milk and flour. Yeast is added to make it rise. The dough is then cut into small shapes and cooked in very hot oil in a qazan. Kazakhs and Kyrgyz always celebrate any feast or occasion with boorsoq. They make it in large quantities at weddings, funerals and memorial feasts, etc. Boorsoq is very good to eat with koumiss, fermented mare’s milk.

In Central Asian markets (the one here is in Osh, southern Kyrgyzstan), flat bread (nan), normally round and with decorations on top, is the most common kind sold. This nan is quite similar to that which one finds amongst the herders in the mountains, but Uzbeks traditionally make the best nans in Central Asia. All varieties of nan are baked in a clay oven and they come in various sizes and shapes. The city of Osh is inhabited mostly by Uzbeks and Kyrgyz. Kyrgyz rarely sell bread in places where many Uzbeks live: They just leave baking and selling for Uzbeks, who are the master bakers.

Hospitality to visitors is an important part of traditional nomadic culture, as we learn, for example, in one of the famous sixteenth-century accounts of the history of Central Asia by Mirza Muhammad Haydar. Naturally, the gift of expensive horses (in addition to the customary sharing of koumiss) which he describes would be restricted to very important guests. But the traditions continue, as illustrated here where the girl shown (above) a year later stirring the milk in the qazan is shyly greeting guests with an offering of qazan nan and yogurt. Especially in the mountains of in Central Asia, if the unexpected guest or stranger who is passing by does not want to come inside the house or yurt, the bread and yogurt are brought outside to him. If people make koumiss, the guest will be offered it with the bread, because it is valued much more highly than yogurt, tea, and water. Therefore, not to drink koumiss when it is offered to you is rude. Although some foreigners do not like the taste of koumiss, at least tasting it is obligatory good manners to show some respect to those offering the hospitality.

Here we see another example of traditional hospitality in a different Ak-Suu Valley of the Pamir-Alai (the name Ak-Suu or "White Water" can refer to any number of mountain streams). The boys are the grandchildren of the old couple. Although the elderly man is wearing an Uzbek traditional cap, duppi, that by itself does not identify him as a Tajik or Uzbek, since some Kyrgyz living in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan also wear a duppi. He is seventy-two years old; his wife sixty-eight. Due to the hard work and the raising of large families, women in these areas tend visibly to age more rapidly than men. During summer vacation, some school children go to the summer pasture to help their grandparents or relatives with their cattle and also to breathe fresh air, drink koumiss and eat dairy products which are not available in towns and cities as everyday food. Grandparents rarely live by themselves in the mountains; they always take one or two of their grandchildren with them.

The third example of traditional hospitality is in a Kyrgyz summer home of the Eastern Pamir, Xinjiang. Prof. Waugh encountered the forty-year-old man (who had just had some kind of dental surgery in town and was wearing a bandage over his front teeth) at a pass and followed him down to his hut, cut into the side of a slope. He and his wife are offering the traditional hospitality of bread and yogurt. Note that the shape of the bread in this picture is different from that in preceding pictures: This is the bread called kömöç (from köm- "to bury"), which is baked in embers, rather than in a qazan. The couple also sent their little girl outside (to a neighbor's home?) for some apples, which obviously would have been brought up from a lower village, since there were no orchards near this high mountain camp. At age twenty-four, the man's wife was significantly younger than her husband; unlike him, she was able to write her name.

Our last example of traditional hospitality shows Elmira Köçümkulkïzï's family and neighbors in Kïzïl-Jar, Aksï region, southern Kyrgyzstan, giving her a blessing at a ceremony honoring her return home. This is the inside of one of those permanent yurts which villagers pitch in their courtyard next to their brick house. The special feast for the occasion, called quday, is a tradition among the Central Asians for which they slaughter a goat or sheep when a family member safely returns from a far away or "dangerous" place, e.g., from the army, a battle or from surviving a deadly accident, etc. In this case, the family is celebrating their daughter’s safe return from her year of study in America. When many people are invited to such feasts, people do not sit for a long time, because they need to empty the yurt for the next group of guests to enjoy the food. After finishing their meal and talking for a short time, they ask the person to whom the feast is being offered to come in and stand in front of them while the eldest person among the group, male or female, gives the main blessing. The others also add their own short blessings. In their blessing, they usually wish the person a long and happy life, good health, prosperity, success in his/her studies or work, etc.

Lastly, by way of anticipating a cookbook of Central Asian food, which we will be posting, we show another of the traditional foods of Central Asia. This is Xinjiang mantï, steamed dumplings, here being put in wooden steamer for cooking in the Kashgar bazaar. Mantï, a favorite dish of Central Asians, came from China. A Chinese word, mantï means "steamed dough." Mantï comes in various shapes depending on the region where people live. The mantï made by the Turkic peoples living in Eastern Turkistan, such as Uyghurs, Kazakhs and Kyrgyz, is similar to Chinese pot stickers, except that it is made of beef or lamb, not pork. Mantï made among the Turkic peoples of Central Asia's newly independent states has a different shape and is cooked in an aluminum rather than a wooden steamer.

Back to Top

© 2001 Elmira Köçümkulkïzï and Daniel C. Waugh. Last updated December 29, 2001.

Silk Road Seattle is a project of the Walter Chapin Simpson

Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington.