|

Individualism became an important strain in painting, calligraphy, and poetry during the middle to later years of the Tang dynasty. As the central political sphere declined, there was an upsurge in localized unorthodox creative activity which seemed to stand outside all previous traditions. Daoist painters got drunk and painted with their hair or dragged each other across the paper’s surface, and their Chan counterparts sought similar release from societal constraints in calligraphy through the use of a new style of writing aptly named “wild cursive.” The moral and civic value attached to modeling oneself on the great early Tang masters of the standard script from Taizong’s court was still recognized, but the new emphasis on individuality, the spontaneous, and the uninhibited marked a profound shift in calligraphic practice from an ultimately conservative tradition to one that favored self-expression and change. As court calligraphers throughout the Tang period were engaged in setting and maintaining a standard for elegant writing in the Wang tradition, the actual forms of calligraphy championed by the court became increasingly conventionalized and stagnant. Wild cursive, a radically modified version of the draft cursive script of the Han dynasty, can be seen as a reaction against the atrophied writing styles of later Wang tradition calligraphers. |

|

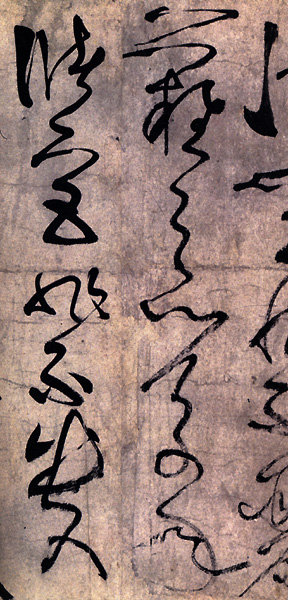

Zhang Xu (active 710-750 AD) was said to be the originator of the wild cursive script. He enjoyed considerable fame in his own day, and is counted among the Tang poet Du Fu’s “Eight Drunken Immortals.” Although wild cursive seems to break radically from all past traditions, Zhang Xu did base his writing style on one of the more prominent earlier calligraphers. It is believed that he was further influenced by the Daoist practice of automatic writing in sand. Zhang Xu’s calligraphic style is widely praised, especially by later scholars, yet one of the by-products of his style is a pronounced deformation of word structures. Of the calligraphers presented in this unit, whom do you think Zhang Xu took as his primary model? What seems to be a salient feature of this writing style, judging from the small sample at left? |

|

|

Zhang Xu (active 710-750), Four Letters on ancient poems, written in wild cursive script, detail

|

|

|

What philosophical traditions in China might have valued extreme unconventionality more than placing oneself clearly within an established tradition or school?

|

|

Below

is a larger section of the detail of the letter shown above.

Can you recognize characters that you’ve seen before? Can

you tell where the brush must have changed speed or received great

pressure? How many people

do you think would be able to read this letter?

|

||||

|

|

||||

|

||||

|

In what script type is this written? Does it resemble the style of any of the early Tang court calligraphers? How do you think each of these two writing samples was executed? What factors do think account for the differences in appearance? |

||||

|

Zhang Xu, Preface to the Lang guan shi ji (641 AD), detail

|

What made the running and draft scripts more attractive for writers and collectors alike than standard script? |

|||

|

Zhang

Xu was also the teacher/model of two calligraphers of the following

generation who were revered for their unorthodox and highly

individualistic styles. The monk Huaisu (735?-800? AD, example shown below) was a

man of letters; also known as the “Drunken Monk,” he followed Zhang

Xu’s wild cursive mode of writing.

In one of the extant examples of his calligraphy, Huaisu

complains about eating bitter bamboo shoots, and also admits his

unbounded passion for liquor and fish.

The sample of Huaisu’s writing below is an autobiographical

essay that includes comments on his own study of calligraphy. What

kind of impression of the calligrapher’s personality or temperament

does the example below give you? Is this a carefully composed piece of

writing? What religious or philosophical traditions do you think had the most formative impact on this mode of writing? |

|

|

|

|

Yan

Zhenqing (709-785 AD) was a leading figure among loyalists to the Tang

throne during the politically turbulent eighth century.

He was a dedicated and brilliant military figure who suffered

great personal loss at the hands of aspirants to the throne yet remained

unswerving in his loyalty to the legitimate ruling house.

Because

of his reputation as a staunchly moral and principled individual, Yan

Zhenqing’s forceful and majestic individual style assumed the heroic

proportions of his own life. One of the requisite techniques of Chinese

calligraphy is maintaining the brush’s upright position in order to

transfer more directly and powerfully the flow of energy from hand to

paper. From Yan

Zhenqing’s time forward, saying someone wrote with an “upright

brush” carried an especially strong tone of moral approbation.

His calligraphy was particularly influential among literati of

the Northern Song, including Su Dongpo and Huang Tingjian.

Evaluative writings on calligraphy often equate the structure (“architecture”) and line quality of the written word with the physical human self. Some examples are criticized for being too “fleshy” while lacking in bone structure. How do you think Yan Zhenqing’s regular script calligraphy would be portrayed in these terms? Why do you think this type of analogy was considered appropriate? |

|

|

|

Yan Zhenqing (709-785 AD), Memorial inscription (745 AD)

|

|

Compare

details from Yan Zhenqing’s regular script inscriptions (examples

below right) with two examples from the more orthodox court tradition

that favored the elegance and ease of Wang Xizhi style calligraphy,

represented by Chu Suiliang from the time of Taizong (below, top left)

and Li Yong, the foremost Wang tradition calligrapher of the first half

of the eighth century (below, bottom left).

Where

can you identify similarities in the shape and angularity of brush

strokes? Which

brush strokes seem to have been made with the most force or pressure? Do you think a particular example stands out in terms of presenting a forceful or distinct personality? Why or why not?

Is Yan Zhenqing’s handwriting easily distinguishable from other examples you’ve looked at throughout this unit? What would you identify as its most distinctive quality?

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Chu Suiliang (596-658 AD), Meng Fashi memorial inscription (642 AD) detail

|

Yan Zhenqing (709-785 AD), Encomium inscription (771 AD) detail

|

||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||

|

|

||||||||

|

Although the majority of calligraphers during the Tang period made their most distinctive contributions to the development of a mature standard or regular script, the cursive script type would in time be the most favored for its ability to express the individual calligrapher’s aesthetic preferences and inner character. |

||

|

Do either of these seem to be a more intentionally aesthetic object? Why or why not?

|

||

|

Huaisu

(735? – 800? AD), Autobiographical Essay, detail

|

||

The content of the letter written by Yan Zhenqing, left, recounts the political circumstances under which his nephew was executed.

|

||

|

Yan Zhenqing (709-785 AD), Lament for a nephew (letter), detail

|

||

|

Although it is riddled with mistakes and corrections, this example of Yan Zhenqing’s writing has been especially valued by connoisseurs. What qualities do you think might make this more attractive than a polished, well-executed piece of calligraphy? |

||

|

Move on to Calligraphy in Modern China |