In 1923, when asked about the potential of organizing a workers revolution in the United States, Anne Louise Strong told Leon Trotsky that he was better off focusing his organizing efforts elsewhere.[1] The American writer, journalist, and labor activist spent the latter part of her life advocating workers’ rights in Russia and China, but always looked back on her home country with the wistfulness of missed opportunity. This resigned attitude concerning the American labor movement wasn’t the result of any lack of effort on her part. She’d spent her young adult life in the US organizing in one way or another, first as a liberal advocate for social change and employee of the National Child Labor Committee; then as a progressive pro-labor writer and school board member in Seattle; then as a radical journalist who helped guide the Seattle General Strike in 1919.

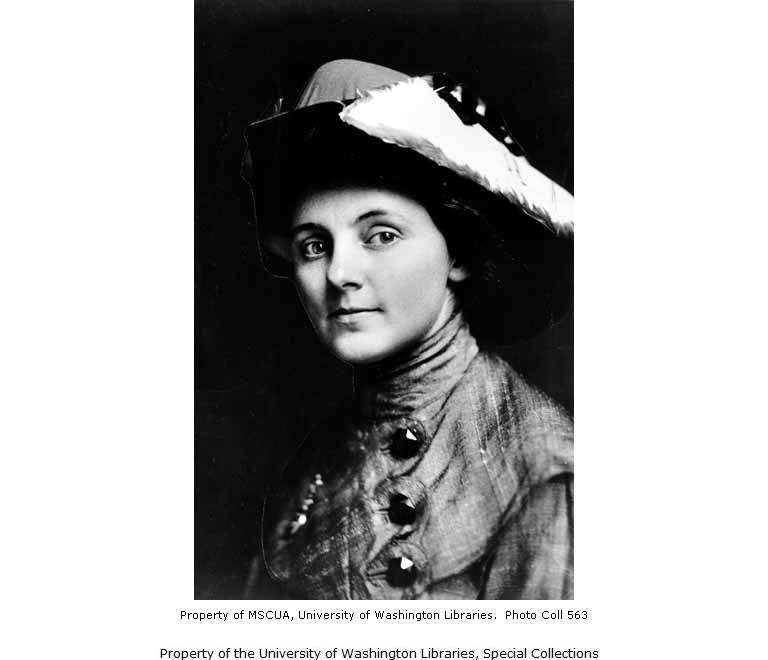

Despite her prolific writing career and decades of advocacy nationally and internationally, Anna Louise Strong has faded into obscurity even in the state that witnessed the highlights of her American activist career. This essay details her Seattle years, from 1916-1921. During that time the city knew no more prominent crusader for social justice. The first woman to hold public office, she spent a year on the school board in 1916 before facing a recall election because of her radical and antiwar views. Nearly indicted during World War I for speaking against the war, she built a career as a journalist defending the Industrial Workers of the World, and then as a writer for the Seattle Union Record, the daily newspaper published by a Central Labor Council, and was later arrested for her role in promoting the Seattle General Strike in 1919. Two years later, in 1921, she abandoned the labor movement in the Pacific Northwest and moved to the Soviet Union to continue her activist work in a place she believed would see meaningful change in a way the US was then incapable of in her eyes.

Strong’s politics and philosophy would shift over the years as she experienced the full scope of worker movements in Russia and China, but her time in what was briefly considered the most radical city in the United States is a case study in the rhythms of American radicalism where surging optimism could be followed by political repression. Her forced removal from the Seattle School Board is one example, but she was also invested in the defense of other labor activists who were persecuted for anti-war activities. This persecution was deeply personal for all involved: the workers threatened, the Seattle politicians who felt compelled to clean up Seattle's public image on the national stage, and the business leaders interested in suppressing labor organizing at any cost.[2] Dissecting her life and career in Seattle provides us with insight into the life of a remarkable woman and also into the political dynamics of Seattle in a pivotal moment in its history.

Activist Origins

Anna Louise Strong didn’t grow up a member of the working class. Members of her family tree had been responsible for founding the towns of Northampton and Hadley in Massachusetts in the 17th century and later the town of Strongsville in Ohio. Her ancestors included founders and early graduates of Harvard and Yale. Her parents were both college educated, having met at Oberlin College in 1880. Sydney Strong was a progressive minister and Ruth (Tracy) Strong balanced the duties of motherhood with social work that Anna Louise remembered with pride.[3]

She admired her parents' politics and gave them much credit in shaping her social ideals when she discussed her decidedly middle-class childhood in her autobiography. “My father was one of the first in his generation to embrace the doctrines of Darwinism and evolution and many struggles it cost him some fifty years ago. My mother was one of that first generation of women anywhere in the world to receive a college education…It was in Oberlin, of anti-slavery traditions, whose very college motto is ‘learning and labor’ from the days when students built the college with their hands, that she met my father. Their marriage followed the new progressive tradition that wives are not only partners in pioneer hardships but equals in brains.”[4]

Anna Louise and her two siblings grew up in a household that championed love and equality, but education first and foremost. Twenty-six years after the publication of her carefully curated and somewhat idyllic autobiography I Change Worlds Anna Louise admitted to her friend Helen Tompkins that she’d often felt as if academic excellence was one of the only ways she could gain the approval of her parents, who often found their attention taken by either her siblings or the pressing social issues of the time. Anna Louise did not seem to begrudge the work they accomplished, but instead tentatively traced the loneliness that followed her all her life to these family dynamics.[5]

However, she also credited her unshakable sense of justice to this same upbringing, particularly her mother’s dedication to exposing Anna Louise to people outside of her white middle-class bubble. Ruth, raised in the unwaveringly anti-slavery part of northern Ohio, allegedly punished Anna Louise for expressing racial prejudice as a child and later encouraged her to socialize with local Black children her own age to the apparent horror of their neighbors.[6] Later on a trip through Tacoma, Washington, Anna Louise would remember her mother taking her to an unsegregated “people’s” restaurant. For a seemingly innocuous experience to be noted with so much weight this was possibly Strong’s first exposure to the idea of working-class spaces as a place for the nebulous socialist concept of “the people". Ruth’s letters to her husband during this trip make specific note of then eleven-year-old Anna Louise’s growing political awareness as she immersed herself in the political discussions happening around her.[7]

Her exposure to working class issues continued throughout her teenage years, despite the elite private education she was receiving. She credited her discovery of poverty with teaching sewing with her mother on Chicago’s west side. The prevailing ideology of the time credited institutional poverty to ignorance and a lack of morality.[8] Even before her introduction to socialism, this didn’t sit well with Strong, who remembered questioning her mother’s dismissal of economic theories of publicly owned wealth and equal division of resources.

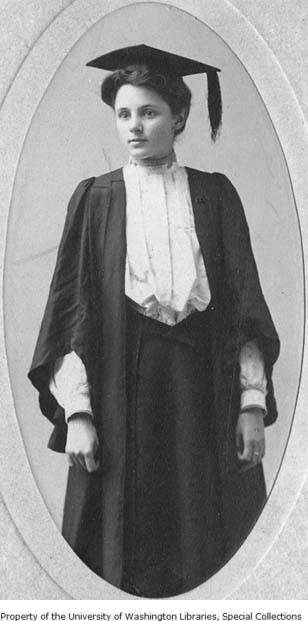

Seeking answers in higher education, she first spent a year studying at Bryn Mawr College before following in her parents’ footsteps to Oberlin, graduating in 1905 as she turned 20. Not yet old enough for a respectable job, she pursued a postgraduate degree in philosophy at the University of Chicago. She was living on her own for the first time and–when the semester ended–she started working at Sprague-Warner’s, a canning plant for fruits and vegetables. It was during her time at this factory job that she was truly exposed to the economic conditions of working life in the US, witnessing firsthand the day-to-day realities of her coworkers’ lives. She ended up feeling that her time in the workforce was more educational and useful than her philosophy classes, even when she was forced to quit her factory job to focus on her degree.[9]

Upon her graduation in 1908 she was the youngest student at age 23 and one of the first women to earn a PhD from the university, but she was less than enthused about her time spent in higher education. “I felt no love for the philosophy on which I had ground my mind for two and a half years to prove that I could do it, and which I had now triumphantly conquered: I hated it. To this day I have never willingly opened a book on philosophy.”[10]

Her time spent in the workforce as well as her time involved in social work through settlement houses in Chicago provided inspiration for her budding career. She had been writing since she was a young girl and had continued to write through her undergraduate and postgraduate years but began to seriously consider it as a career. Her work and professional connections eventually led to her involvement with the National Child Labor Committee, a progressive organization that advocated social progress. She spent the next few years traveling the continental United States, setting up exhibits and giving educational lectures geared towards improving the quality of life of impoverished Americans. As she became more educated on socialism the more disengaged she became with her committee work, feeling that the poverty she witnessed couldn’t be improved by capitalist progressivism alone.[11] She halfway resigned from the organization in early 1914 and travelled to Ireland where she became a quick supporter of the movement for Irish home rule, interviewing citizens about their struggle for national freedom.[12] However, this work was cut short when World War I began in Europe. Feeling that individual effort was useless in the face of such mass violence, she returned to the US.[13]

She moved to Seattle, living with her father, and soon realized that her past experience with the National Child Labor Committee made her the perfect candidate for the Seattle School Board.

She was easily elected, to the jubilation of the labor movement who saw her appointment to the board as a win against the business interests that they viewed as having corrupted the public education system.[14] Strong would spend most of her time on the board debating the cost of heating and the replacement of light fixtures, but she also used her position as a public official to advocate for and defend pro-labor interests.

The Everett Massacre and IWW Defense

In May 1916, the International Shingle Weavers Union, an affiliate of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), went on strike. Workers employed by the mills that populated the Pacific Northwest spent long days feeding wood through automated saws before “weaving” the shingles together in bundles.[15] The only protective gear provided was a sponge tied over the mouth and even that often couldn’t prevent the occupational hazard known as ‘cedar asthma’ from being extremely common. If a worker somehow managed to avoid any respiratory issues it was only a matter of time before he lost a finger or hand to the rapidly spinning blades that spat out shingles near constantly. In 1915, wage cuts sparked the outrage that prompted the coordinated strike throughout the state and by August of 1916 nearly every mill involved had either won their strike or called it off. All except the workers at the Jameson mill in Everett, Washington.[16]

On August 19th, Everett picketers were beaten by a group hired by the Jameson mill owners. In response the police imposed an emergency ordinance that prohibited speechmaking in Everett’s downtown. Ordinances against free speech and assembly were commonly used against striking unions and their supporters. Everett union members knew that this ordinance had been passed with the intent of shutting down their strike. Even though the union involved was affiliated with the AFL, members of the IWW joined forces once they heard of the brutality targeting strikers and police involvement in suppressing union organizing.[17]

The IWW’s involvement sparked panic in Snohomish County authorities who, led by Sheriff Donald McRae, assembled a group of about two hundred “citizen deputies” to take action against any “Wobblies” who set foot in Everett. Known for bold tactics and revolutionary rhetoric, the IWW were widely feared by business interests and portrayed in newspapers across the country as violent radicals. Sheriff McRae, who already had a reputation for violently targeting Wobblies, assembled his citizen deputies and prepared for a shootout. The IWW meanwhile, held a rally in Seattle on November 5th and several hundred members boarded the steamships Verona and Calista for the 25-mile sail to Everett.

On arrival, shortly after the Wobblies refused the Sheriff’s command to turn around, gunfire erupted. The events that followed became known as the Everett Massacre or “Bloody Sunday” in which at least five Wobblies were killed and 27 wounded. On the opposite side Sheriff McRae was counted among the twenty or so wounded and two citizen deputies lay dead. When the steamers returned to Seattle, every single IWW member on boardwas arrested and later 74 were taken to the Snohomish County jail and charged with conspiracy and murder.[18]

It was at this moment that Anna Louise Strong became relevant to the defense of the indicted Wobblies. She visited the men in jail and published an account in Survey magazine recounting their mood:

“The boys in jail are a cheerful lot. The 'tanks' which contain them are the tanks of the usual county jail, much overcrowded now by the unusual number. Bunks crowded above each other, in full sight thru the bars; a few feet away, all the processes of life open to the casual beholder. But they sit in groups playing cards or dominoes; they listen to tunes played on the mouth-organ; most of all they sing. They sing whenever visitors come, and smile through the bars in cheerful welcome. Theirs is the spirit of the crusader of all ages, and all causes, won or lost, sane or insane. Theirs is the irresponsibility and audacious valor of youth. When they disliked their food, says a conservative newspaper, they went on strike and 'sang all night.' Sang all night! What sane adults in our drab, business-as-usual world would think of doing that? Who, in fact, could think of doing it but college boys or Industrial Workers of the World, cheerfully defying authority?"[19]

Her detailed account was overtly sympathetic toward the Wobblies, an opinion shared by the broader labor movement and many respectable citizens in Seattle who blamed McCrae for the violence. Seattle Mayor Hiram Gill made a public statement three days after the massacre claiming that the IWW was innocent of inciting violence. He called the citizen deputies cowards and imbeciles who had had no legal right to prevent the Verona from landing.[20] Strong, by then an established member of the Seattle School Board and Executive Secretary of the Seattle Council of Social Agencies, used her connections in the city and on the east coast to land a position covering the trial for the New York Evening Post. She ostensibly approached the conflict as an unbiased outside observer, but certainly by the end had become an impassioned public advocate for the Wobblies. Her files even contain a pamphlet intended for raising funds for the defendants that she’d apparently typed and corrected, indicating that she might not have approached the trial as neutrally as she went on to claim in her autobiography.[21]

During the first trial of Thomas Tracy, she made sure the Post was printing what she said was a “description of raw injustice on the Pacific Coast”. Her opinion at the time was that the average American would be horrified by the obvious excess of brutality demonstrated by the police of Everett and she was vindicated when a jury found Tracy not guilty after long debate. Her reporting from the trial highlighted the torture of imprisoned IWW members by the Everett police, as well as the multitude of lies they were caught in on the stand.[22] This involvement in the defense of Tracy deepened her connections with other members of the IWW, and she began to spend time with organizational leaders that were based in Seattle.[23]

At a time when IWW members were in constant danger from regular citizens and government officials alike, Strong’s coverage of the trial was notable for the voice it gave to those involved in the organization. She interviewed members on their lived experiences, some of which were typed into a document titled “From the Under Side: What the IWW in the woods are saying about the situation” which provided rare insight into the often purposefully misrepresented motivations of those who joined the organization. One of the workers interviewed even made specific mention of being pro-government in response to the common accusation of the IWW being pro-German and anti-war, something that would become personally relevant to Strong in the following years.[24]

Strong vs. Seattle School Board

Already marked as a radical because of her progressive politics before the Everett trial, once she returned to Seattle Anna Louise was the object of increased scrutiny. This was partially due to a general fear of IWW radicalism among business leaders, but was exacerbated as talk of the United States entering World War I ramped up. Strong was staunchly anti-war, an ideology that she’d inherited from her father. Sydney Strong was a pro-labor anti-war minister in Seattle at the time, and Anna Louise’s brother Tracy had been jailed for pacifism.[25] The IWW took a vocal anti-war stance in contrast to the AFL, who were of the belief that supporting businesses in wartime would eventually lead to an increase in worker wages. Strong’s anti-war beliefs resulted in her collaboration with the IWW in organizing for peace. Before war was declared she helped organize the Seattle branch of the American Union against Militarism, which involved surveying civilians to gauge popular support of the war before sending the results by telegram to Congress daily.[26] She also used her position on the school board to prevent pro-war organizations from using Seattle high schools to recruit underage men for the military.[27] She vehemently disagreed with the very idea of war being declared without a referendum of the people and stood by her anti-war statements even when faced with accusations of anti-Americanism.[28]

Once the United States entered World War I in 1917, Strong lost faith in her country. “Nothing in my whole life, not even my mother’s death, so shook the foundations of my soul. The fight was lost, and forever! 'Our America' was dead! The profiteers, the militarists, the “interests” had violated her and forced her to do their bidding. I could not delude myself, as some did, that this was a 'war to make the world safe for democracy'; I had seen democracy slain in the very declaration of war. The people wanted peace; the profiteers wanted war–and got it. There had been a deep mistake in the basis of my life. Where and how to begin again I had no notion.”[29] Her deeply held convictions concerning the quintessentially American value of democracy that left her so heartbroken at the war's outset made it horribly ironic when the recall election held for her position on the school board targeted her for being unpatriotic.

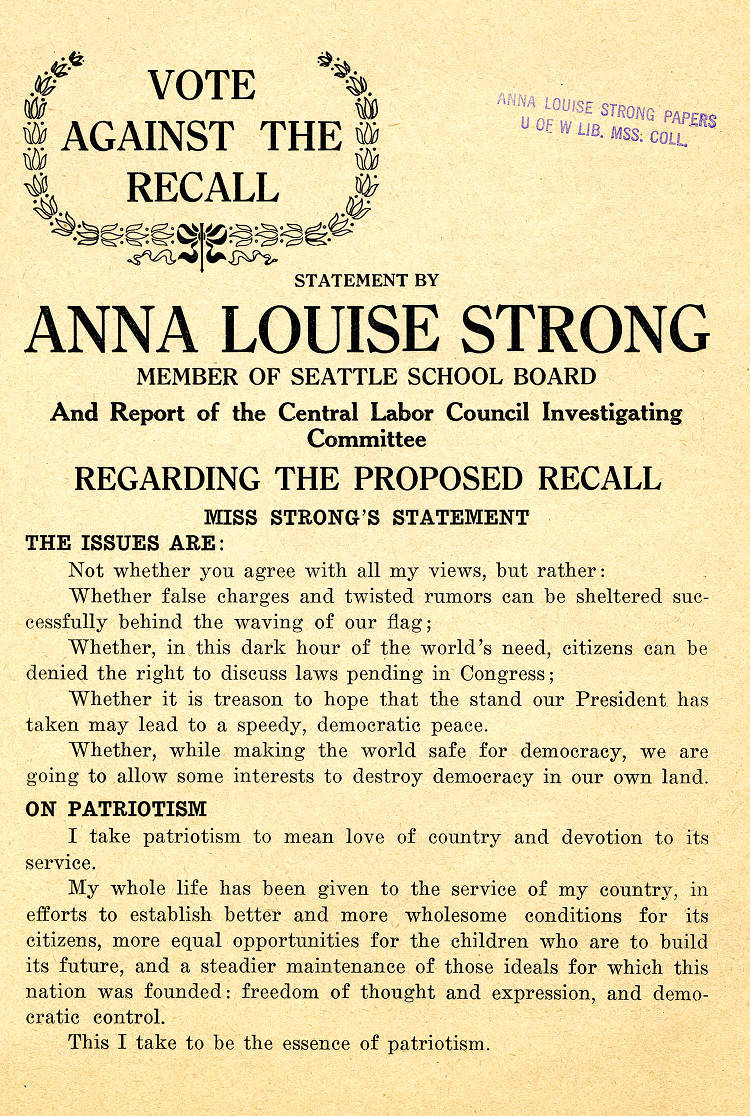

Allegedly filed by three veterans of the Spanish-American war–a fact stressed by every major newspaper that covered the recall election–the case against Strong targeted her specifically for her anti-draft activities. They alleged that her participation in an anti-war meeting and involvement in printing anti-war pamphlets placed her in violation of the oaths she’d taken as a school board member to support the constitution of the United States. “Above all else, American public schools are supposed to teach loyalty, patriotism, and allegiance to the flag” proclaimed The Seattle Times, “no patriotic American citizen can agree with this sentiment. It is the same kind of pro-German propaganda the government has had to fight for months past.”[30]

This charge of pro-German loyalty was commonly thrown at anti-war IWW members, whose union had German immigrant origins, and Strong’s previous association with Wobblies made the accusation of disloyalty stick. In the scrapbook that she compiled of most articles referring to the recall, a vandalized election flier showcases just how vehement her denouncers could be regarding the anti-war side of the labor movement. “I would like to hang you and your father,” it reads, alluding to the fact that Sydney Strong had been expelled from the some organizations and was under scrutiny by the Ministerial League of church leaders for alleged support of the IWW. “You know what happened to your ilk in Tulsa” it went on to threaten in reference to the tarring and feathering of anti-war IWW members by a nationalist pro-war organization known as the Knights of Labor. “We want real Americans on our school board” the flier concludes, leaving no doubt in the mind of the reader what the sender thought of anyone who had any connection to the IWW’s anti-war beliefs.[31]

Anna Louise Strong’s other connections to anarchists and socialists did not help her case. In 1917, she had testified in support of socialist and former mayoral candidate Hulet Wells when he was on trial for sedition, under a recently enacted law against anti-war speech. Acquitted in the first trial in part because of Strong’s effective testimony, Wells was retried, convicted, and sentenced to a long term. Anna Louise had also befriended the proud anarchist Lousie Olivereau, who was arrested for sending seditious literature to drafted soldiers. In November of 1917, Olivereau was sentenced to ten years in prison under the Espionage Act for printing leaflets that allegedly interfered with the draft. Despite Strong’s public proclamation that her support for Olivereau was based on professional journalistic ties not political agreement, the association with an “anarchist” hurt and the recall election gained momentum.[32]

While establishment newspapers refused to cover her side of the story, Strong had support from her associates in the labor movement and was able to print her defense in the progressive Seattle Union Record. She claimed that she hadn’t participated in anti-conscription activities after the date that war had been officially declared and that she had no knowledge of the contents of the anti-draft pamphlet that had been published after a meeting that she admitted to attending. She refused to back down from her anti-war beliefs however and used the increased attention to advocate for “no indemnities, no annexations, and free development for all nationalities.” Did she truly not participate in anti-draft organizing after the declaration of war? Did a woman known for being frighteningly aware of the exact machinations of every meeting she attended really not know the contents of the pamphlets she helped print?

In the end, whether or not she was telling the truth wasn’t the real issue. The Seattle Times was quick to explain, “Miss Strong’s pacifist activities, however ‘within the law’ fail to meet the acid test. Her Americanism has been challenged. Out of sympathy with the war, out of sympathy with the draft, Miss Strong has permitted her loyalty to the country and its aims to be placed in serious doubt…Seattle must accept that challenge. There must be no doubt as to how this city stands. Anna Louise Strong and her brand of ‘patriotism’ must be overwhelmingly defeated at the polls.”[33] She wasn’t recalled from the Seattle School Board in 1918 for any specific legal transgression, but instead for being anti-war in a country that was making an example of labor activists under the pretense of being unpatriotic.

General Strike

Anna Louise Strong joined the IWW during a period of intense persecution and coordinated repression. Between 1917 and 1920 federal raids across the country resulted in mass arrests of the organization's members. Meeting halls, headquarters, and affiliated pro-labor newspapers were all targets of political violence. With American politicians unsettled by the success of the Russian Revolution and the imagined workers revolution it could inspire in the United States, Bolsheviks and anarchists were demonized by the mainstream press and regularly threatened with deportation.[34]

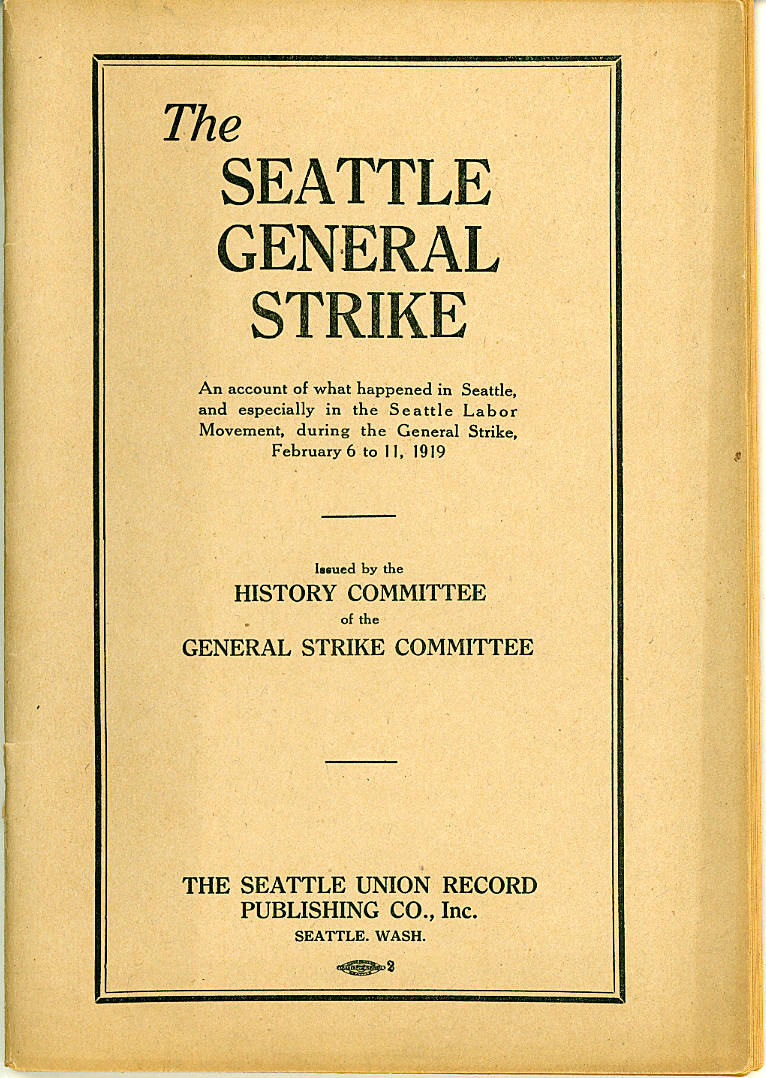

After her dismissal from the Seattle School Board, Strong turned more completely towards journalism, initially writing for the socialist Daily Call. After vigilantes smashed the Daily Call printing presses and shut down the paper, she was hired by the Union Record, published by the Seattle Central Labor Council.[35] Her journalistic reputation was by then firmly established and editor Harry Ault welcomed her talents. She played many roles, covering news events, writing editorials, and under the alias “Anise” writing a column addressed to women readers. Her most famous contributions came during the preparations for the Seattle General Strike in early 1919 when she authored the soon to be infamous front-page call to action that carried the simple headline “On Thursday at 10 A.M.” -- the date and time the strike was set to begin:

“There will be many cheering and there will be some who fear. Both these emotions are useful, but not too much of either. We are undertaking the most tremendous move ever made by LABOR in this country, a move which will lead--NO ONE KNOWS WHERE!

We do not need hysteria. We need the iron march of labor. LABOR WILL FEED THE PEOPLE. Twelve great kitchens have been offered, and from them food will be distributed by the provision trades at low cost to all. LABOR WILL CARE FOR THE BABIES AND THE SICK. The milk-wagon drivers and the laundry drivers are arranging plans for supplying milk to babies, invalids and hospitals, and taking care of the cleaning of linen for hospitals. LABOR WILL PRESERVE ORDER. The strike committee is arranging for guards, and it is expected that the stopping of the cars will keep people at home.”[36]

The citywide strike ended after only five days as unions realized that they had miscalculated. Federal authorities rejected all proposals and sent Army units from Fort Lewis while Mayor Ole Hanson, who in earlier times had seemed to be labor friendly, condemned the strike and threatened martial law. [37] Looking back years later, Strong lamented the strike’s organizational and ideological shortcomings, “All of us were red in the ranks and yellow as leaders. For we lacked the intention of real battle; we expected to drift into power. We loved the emotion of a better world coming, but all of our leaders and not a few of our rank and file had much to lose in the old world. The general strike put into our hands the organized life of the city–all except the guns. We could last only until they started shooting.”[38]

Leaving America

The general strike may have ended without any material benefits for the workers involved, but it succeeded in scaring the government and business leaders into launching an all out campaign against radicalism in what would become known as the “First Red Scare”. The IWW hall and the Socialist Party headquarters in Seattle were raided shortly after the end of the strike and their leaders arrested. Anna Louise Strong was arrested alongside the other editorial staff when federal agents raided the Union Record for “attempting to incite, provoke, and encourage resistance to the United States.”[39]

Strong was released on bail but was again the subject of accusations of anti-Americanism. She felt disillusioned as the evolving red scare took its toll and many AFL unions turned away from radicalism. She continued to write for the Union Record authored a now classic report on even as it became more and more divided ideologically. She was a staunch believer in the IWW’s ideology and more and more felt unwelcome in the emerging capitalist labor movement. A meeting with Lincoln Steffens, an American journalist returning from a visit to the Soviet Union, was the final push she needed to seek fulfillment elsewhere. Disillusioned with her job and feeling that her radical reputation was doing more harm than good to her family, she made the decision to uproot her life and move somewhere she felt her work would make a real difference.[40] After years of enduring anti-communist persecution from all sides in the US, she finally felt free.[41] The Soviet Union at that time was just starting out, a fletchling country that she felt embodied the spirit and aims of the general strike before it dwindled. Seattle had been profoundly influential to her outlook on the entire American labor movement that she would end up discussing in less than flattering terms with Trotsky in the following years. She may have felt pro-worker revolutionary change was “too remote to be practical politics”[42] in the United States due to her experiences in Seattle; but her time spent in the anti-war movement and in support of the IWW at a time when anti-communist fervor was sweeping the United States laid the ideological groundwork for decades of unwavering dedication to workers movements in Russia and China. Writing years later in 1940, she again contemplated the American labor movement, this time within the context of the rise of global fascism. “Who shall own and command America–the people or the [war] profiteers? This is the great question of our time. This is the question whose answer will affect the course of world history.”[43]

HSTAA 498 Fall 2024

[1] Letter to Sydney Strong, January 20, 1923, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 3, booklet, UW Special Collections.

[2] Scrapbook, 1917-1918, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 1, UW Special Collections.

[3] Strong Tracy, Right in Her Soul, pp. 11-15.

[4] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 5.

[5] Strong Tracy, Right in Her Soul, pg. 15.

[6] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 18.

[7] Strong Tracy, Right in Her Soul, pp. 18-19.

[8] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pp. 40-43.

[9] Strong Tracy, Right in Her Soul, pp. 44-46.

[10] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 34.

[11] Letter to Sydney Strong, 1914, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 3, folder 2, UW Special Collections.

[12] Manuscript “Human Aspects of the Irish Situation”, 1914, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 3, folder 5, UW Special Collections.

[13] Letter to Sydney Strong, July 1914, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 3, folder 6, UW Special Collections.

[14] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 51.

[15] Smith Walker, The Everett Massacre: The History of Class Struggle in the Lumber Industry (1917), pp. 27-29.

[16] Smith Walker, The Everett Massacre: The History of Class Struggle in the Lumber Industry (1917), pg. 32.

[17] Smith Walker, The Everett Massacre: The History of Class Struggle in the Lumber Industry (1917), pg. 33.

[18] Smith Walker, The Everett Massacre: The History of Class Struggle in the Lumber Industry (1917), pp. 89-106.

[19] Smith Walker, The Everett Massacre: The History of Class Struggle in the Lumber Industry (1917), pg. 112.

[20] The Seattle Times, “Mayor Gill Says I.W.W. Did Not Start Riot”, November 26, 1916.

[21] Broadsheet, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 6, folder 72, UW Special Collections.

[22] Manuscript, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 6, folder 70, UW Special Collections.

[23] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 55

[24] Manuscript, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 6, folder 70, UW Special Collections.

[25] Strong Tracy, Right in Her Soul, pg. 67.

[26] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pp. 56-57.

[27] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 52.

[28] Scrapbook, 1917-1918, Anna Louise Strong Papers, Box 1, UW Special Collections.

[29] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 57.

[30] The Seattle Times article, scrapbook, 1917-1918, Anna Louise Strong Papers, box 1, UW Special Collections.

[31] Scrapbook, 1917-1918, Anna Louise Strong Papers, Box 1, UW Special Collections.

[32] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pp. 61-64.

[33] Scrapbook, 1917-1918, Anna Louise Strong Papers, Box 1, UW Special Collections.

[34] Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 3, 1918.

[35] Strong Tracy, Right in Her Soul, pg. 69.

[36] Strong Anna Louise ‘Anise’, “Thursday at 10AM”, Union Record, February 4th, 1919.

[37] Strong Anna Louise, The Seattle General Strike: An account of what happened in Seattle and especially in the Seattle Labor Movement, during the General Strike, February 6 to 11, 1919, pp. 58-63.

[38] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pp. 81-82.

[39] Strong Tracy, Right in Her Soul, pg. 79.

[40] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pp. 88-90.

[41] Strong Anna Louise, I Change Worlds, pg. 96.

[42] Letter to Sydney Strong, January 20, 1923, Anna Louise Strong Papers, Box 3, booklet, UW Special Collections.

[43] Strong Anna Louise, My Native Land, pg.299.