On October 19, 1977, the United States Commission on Civil Rights (CCR) convened in Seattle for two days of hearings concerning Native Americans in Washington State. The Commission interviewed state, county, and city government officials, as well as tribal leaders and various tribal social service workers, hoping to gain a comprehensive view of the civil rights issues affecting Indians in the Northwest and to devise mutually beneficial resolutions in its recommendations to the President and Congress. The hearings were in large part a response to mounting tension between local government and business interests and Native American communities over the issue of tribal sovereignty. The 1970s witnessed an important shift in federal Indian policy as the post-World War II policy of termination, relocation, and assimilation gave way to greater emphasis on self-determination for native groups and a renewal of government services and treaty obligations. The policy shift prompted a backlash among some non-Indian citizens and government agencies who resented what they considered to be special privileges afforded to Native Americans, especially with regard to Indian fishing rights. The CCR hearings in Seattle provided a public forum for these issues, one that included Indian voices as well as white, and thus mark an important moment in the larger debate over sovereignty, civil rights, and the relationship between government and native groups in American society.

From Termination to Self-Determination: Federal Indian Policy

In August 1953 Congress unanimously passed House Concurrent Resolution 108. The resolution signaled a turn in federal Indian policy, one emphasizing the increased assimilation of Native Americans into mainstream society. Reservations around the country were targeted for termination and Indians were encouraged to relocate to urban centers. Ostensibly, HCR 108 only changed the status of Indians from “wards of the United States” to ordinary citizens with the same rights and responsibilities as all other Americans.1 But terminating reservations meant that the federal government was abrogating preexisting treaty obligations and abdicating responsibility for funding social services to Indian communities. Another measure, Public Law 280, took termination of Indian rights even further by shifting the responsibility for Indian reservations from the federal government to individual states. By giving state governments the right to extend their civil and criminal jurisdiction over reservations without the approval of the tribe, PL 280 effectively nullified tribal sovereignty and legal jurisdiction over its members.2

The termination tide began to change in the 1960s under Lyndon B. Johnson’s “Great Society.” Anti-poverty initiatives such as the Community Action Programs were particularly applicable to Indian communities. Community Action Programs enabled Indian tribes to apply for federal government grants for economic projects on their reservations and then retain local control over the implementation of funds. In 1968 Congress passed a resolution repudiating HCR 108. The most significant piece of legislation in the Johnson era, however, was the Indian Civil Rights Act (ICRA), also passed in 1968. The ICRA repealed PL 280, giving back legal jurisdiction over reservations to the tribes and, according to James Rawls, “extended to Native Americans (and exempted them from) certain protections guaranteed by the Constitution.”3

The Nixon administration continued to roll back termination in the early 1970s. In December 1970, Congress restored 48,000 acres of terminated reservation land to the Pueblo in New Mexico. The next year, the landmark Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act recognized the land and mineral rights of Alaska natives and returned contested land to tribes in Oregon and Arizona. And in 1973, Congress restored federal recognition of the Menominee tribe in Wisconsin, which had been terminated in 1954. As Joane Nagel has written, the series of bills enacted in the early seventies “rang out the death-knell of termination and signaled the new era of self-determination.”4

Rawls points out that the dismantling of termination had less to do with Nixon’s genuine sympathy for the Indian cause than with his “desire to destroy Indian militancy.”5 Indeed, the late sixties marked the emergence of Red Power as activists from American Indian Movement (AIM) took possession and occupied Alcatraz Island in San Francisco in 1968 to protest American Indian poverty. Indian militants staged other sieges around the country from 1968 to 1972, including a takeover of Fort Lawton in Seattle’s Discovery Park in 1970. Civil rights and anti-poverty legislation, then, was not simply the result of enlightened government, but rather reflected government’s response to the grassroots pressure of Indian activists.

With all of these prior achievements, the most important piece of Indian civil rights legislation was passed during the administration of President Gerald Ford. In 1975 Congress enacted the Indian Educational Assistance and Self-Determination Act. The act reduced the power of the Bureau of Indian Affairs to control tribal finances. Instead, Indian tribes could decide for themselves what was in their best interests and where to allocate funding. In the process, the act helped change the tribal relationship with federal, state, and local governments. As Nagel argues, the Indian Educational Assistance and Self-Determination Act “provided a reaffirmation of the federal government’s trust responsibility to Indian tribes as well as Indians’ sovereign rights to independence from local and state regulation.”6

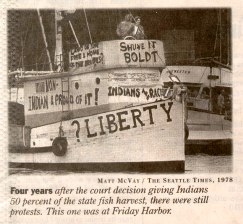

In the Northwest, the debate over Indian sovereignty and civil rights intensified on February 12, 1974 when U.S. District Court Judge George Hugo Boldt handed down an historic decision on behalf of Native American fishing rights. Boldt upheld the authority of treaties signed in the 1850s which guaranteed Native fishing rights in the “usual and accustomed” places, thereby ensuring that Indians were entitled full access to their ancestral fishing grounds.7 Boldt’s ruling further specified that fifty percent of all harvestable fish be reserved for Native fishermen. This victory for the Native Americans was a crushing blow to the non-Indian commercial and sports fishing industries.

The Boldt decision was both a momentous victory for Northwest Indians and a turning point in relations between Native Americans and the local government and non-Indian citizenry. It continued the path toward self-determination laid out in the Congressional legislation of the late 1960s and early 1970s and was thus one of the many positive results emerging from the civil rights movement of the 1960s. However, what Indians considered a great victory set off a new round of conflict between white fishermen and some property owners who questioned why such a small population was granted such a large portion of the fish harvest.

For the next three years leading up to the Commission on Civil Rights hearing, tensions mounted as non-Indians tried to overturn what they considered the Boldt decision’s reverse-discrimination in the form of special privileges handed to Indians. On September 12, 1977, just one month before the CCR hearing convened, Republican Washington State Congressman John Cunningham introduced HR 9054 in the U.S. House of Representatives. The bill, euphemistically named the “Native Americans Equal Opportunity Act,” was an attempt to reverse the course of federal Indian policy back toward termination. It called for the abrogation of all treaties signed between the United States and Native American tribes and held that every citizen or group of citizens of the United States should have no special or subordinate privileges over any other group. In effect, HR 9054 called for the termination of tribal sovereignty. Although it was eventually defeated in Congress, HR 9054 reflected the attitude of many white Americans in the Pacific Northwest in the aftermath of the Boldt decision. Many non-Indians believed that the special privileges that Native Americans had received as a result of Boldt’s ruling gave Indians a type of “supercitizenship;” the resulting prejudice has been termed a “white backlash.”

Sovereignty versus Supercitizenship

The Commission on Civil Rights was created in 1957 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower to “monitor the status of civil rights in the United States.”9 Originally intended to last only two years, the CCR still operates almost fifty years later. The eight-member commission must contain an equal number of Democrats and Republicans, with four members appointed by the President and four by Congress. The group’s mission was and still is:

To investigate complaints alleging that citizens are being deprived of their right to vote by reason of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or by reason of fraudulent practice.

To study and collect information relating to discrimination or a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice.

To appraise federal laws and policies with respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin, or in the administration of justice.

To serve as a national clearinghouse for information in respect to discrimination or denial of equal protection of the laws because of race, color, religion, sex, age, disability, or national origin.

To submit reports, findings, and recommendations to the President and Congress.

To issue public service announcements to discourage discrimination or denial of equal protection of laws.10

The October 1977 CCR hearing in Seattle was an attempt to resolve a longstanding conflict between non-Indians and local government and Indian communities, a conflict that stretched back centuries but had reached a new level of urgency in the wake of the Boldt decision and the twists and turns of federal Indian policy since the 1950s. The Seattle hearing was chaired by Arthur Flemming,11who explained the Commission’s purpose in his opening statement:

The purpose of the hearing is to collect information concerning legal developments constituting a denial of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution because of race, color, religion, sex or national origin, or in the administration of the justice, particularly concerning American Indians; to appraise the laws and policies of the Federal Government with respect to denials of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution because of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, or in the administration of justice, particularly concerning American Indians; and to disseminate information with respect to denials of equal protection of the laws under the Constitution because of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin, or in the administration of justice, particularly concerning American Indians.12

Flemming then introduced Commissioner Frankie M. Freeman who outlined the procedures for the hearing.13 Freeman advised the participants that any defamatory testimony could not be admitted in open session, but instead would need to be heard in “executive session” with just the Commission members. Additionally, she warned it was a crime to threaten any persons who testified before the Commission because they were protected under Title 18 of U.S. Code 1501. Dr. Patricia Zell, a longtime advocate for Native rights and a member of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, followed Freeman with a background summary of federal Indian law.14

After the guidelines were established and the history of Indian law given, the hearing began with the first panel of subpoenaed witnesses for the State of Washington: State Representative Mary Kay Becker; Louis Guzzo of the Governor’s Staff for Minority Affairs; State Attorney General Slade Gorton; and Director of State Fisheries Gordon Sandison. Becker was questioned concerning a bill she introduced to the state legislature in 1976 granting retrocession of jurisdiction back to the Indian tribes. The bill was designed to countermand Public Law 280 by taking authority over reservations away from the State and returning it to the tribes. However, the bill was shelved when Becker lost the support of the Indian tribes who had been lobbying on its behalf. According to Becker, the tribes felt it would be better to have PL 280 repealed on a national level as opposed to having repeal confined to just one state.

Louis Guzzo answered questions on Washington Governor Dixie Lee Ray’s Native American policies. Guzzo relayed that Governor Ray had been in conversation with the Conference of Tribal Governments regarding solutions to all the Indian issues in Washington State. According to Guzzo, Ray felt that Indian issues would be “the most important domestic issue in the country,” let alone the state of Washington.15 As he continued, he stated that he and Governor Ray shared the same concern for equality for all citizens of Washington State:

We actually are pondering a double society, and we must be sure that whatever negotiations, whatever discussions, whatever results accrue from any talks or negotiations are not only fair to both Indian and non-Indian but do not conflict with the traditions of this country with regard to individual freedom and rights … we must obtain justice for the Indians but not at the risk of injuries to non-Indians.16

Guzzo then assured the Commission that the Governor’s policies would be in keeping with federal law even if she personally felt the law was not in the best interest of the State. Guzzo concluded his testimony by conveying Governor Ray’s belief in the principle of law and the authority of the courts. Guzzo’s references to a “double society” and “justice for the Indians but not at the risk of injuries to non-Indians” indicated that he believed Indians were treated as supercitizens under the new laws.

Attorney General Slade Gorton was even more critical of what he viewed as Indians’ special citizenship status. He first questioned the authority of the Commission: “I would suggest, however, that the interjection of the Commission into the question of supercitizenship rights of the Indians is neither proper nor appropriate.17 This claim by Gorton and Guzzo that Indians were enjoying supercitizen rights was disturbing to Commissioner Freeman. She pointed out that American society had been double-sided since its inception—with the white majority having access to a “supercitizenship” status all along. She continued, “I’m saying this because to the extent that these statements reflect an attitude that misses the recognition that there has been denial of opportunity to minorities and Indians.”18 As Gorton’s testimony continued, he stated that he was also against repealing Public Law 280. He felt that repealing the law would not be beneficial to anyone and that it would only undermine equality for all citizens. Gorton dismissed the idea that rights protected by treaties signed the previous century were still relevant. What the Commission was concerned with, he argued, was “what we consider to be special rights, particularly those created by treaty, which bear no relationship whatsoever, now or in the future, to past discrimination and which simply substitute one form of what we would consider to be invalid discrimination for another.”19 Gorton concluded his testimony by reaffirming his earlier opinion of special treatment by pointing out that Indians did not pay taxes and had special water and fishing rights.

Gorton’s hostile attitude toward Native Americans at the hearing was not surprising. While his service record to Washington State was impressive, he had long been an opponent of Native American rights.20 An October 1977 article in the _Indian Voice_claimed Gorton had “made a career the past four years of opposing Indian property rights spelled out in the federal treaties over which his office has no jurisdiction.”21 Three years earlier Gorton had been opposing council representing the State against the Indian tribes and their bid to reinstate their treaty fishing rights, the case that resulted in the Boldt decision.22

The last witness for the State was Gordon Sandison, Director of Fisheries. Sandison echoed Gorton and Guzzo’s claims regarding the “supercitizenship” status of natives but stressed that this was the sentiment of the general public in Washington and not his own personal view. He spoke on how the Department of Fisheries was working to comply with the Boldt decision and the challenges it presented — specifically the fact that the Department could not please all parties at once and was condemned by Native Americans, the general public, the sport fishing industry, and the commercial fishing industry at one time or another. In addition, Sandison discussed his thoughts for the solution to managing the state’s fisheries — to let Washington State officials handle Washington State fisheries without the interference of the federal government.

The hearing continued with testimony from Native American representatives. Joe De La Cruz, Mel Tonasket, and Bernie Whitebear were greatly disturbed by the various state officials implying that Indians were supercitizens. From their perspective, the lack of social services and the widespread poverty on Indian reservations made claims of supercitizenship painfully ironic. Mel Tonasket, member of the Colville Confederate Tribal Council, delivered a passionate rebuttal:

I doubt if people in the level of Mr. Gorton or the Governor or any department head would trade places with the so-called “supercitizen” on my reservation and have to live in substandard housing and have an annual income of $2,000 a year and have their kids taken away and put into another race’s home. I just seriously doubt if they would give that up for a special class that we’ve got.23

Joe DeLaCruz, President of the Quinault Indian Nation and a nationally renowned Native American leader, also refuted the notion of supercitizenship.24 He linked it to the rationale behind anti-Indian legislation, which he argued was based on ignorance and empty rhetoric with no factual basis. He also contested one of the pillars of the supercitizen argument – the claim that Indians did not pay taxes: “In the State of Washington, most of the Indian reservations and Indian communities don’t have the super market and the stores and stuff for their produce, so they pay the State sales tax. They pay the State gas tax.”25 These statements helped to squash the idea of supercitizenship.

Another sticking point was how the government distributed Indian appropriations. Bernie Whitebear, also a Colville Confederated Tribal member, addressed this issue.26 Whitebear stated that federal monies earmarked for Indian education took three months on average to arrive. In the interim, grantees were forced to borrow funds against the grant awards. This lessened the overall amount of funds received for the educational programs because of interest and loan fees that were not factored into the original grant sum. All three witnesses concurred that getting any entitlements for their tribes from the federal government was like pulling teeth. The problem was compounded by the layers of administrative paper work and seriously curtailed the development of much-needed programs.

The final issue that was addressed was Indian fishing rights. De La Cruz stated that the Quinault had requested one half million dollars to help with enforcing their fishing rights and that they would work in conjunction with the State. What the Commission overlooked was the larger issue of developing a program of artificial propagation; such a program would have helped take the pressure off of the native salmon stocks and ensure salmon for everyone in the future. Instead, the only issue the government looked at was enforcement to make sure that Indians weren’t breaking the law.

The next group of witnesses was composed of various officials from cities in the Yakima Valley and Yakima Indian Nation. They testified on a range of issues, including the question of who had jurisdiction over the approximately eighty percent of reservation residents who were non-Indian. Other testimony focused on the fact that Indians were exempt from paying taxes. Witnesses also spoke of the resentment non-Indian whites living on the reservation felt toward the Yakima, which fueled the white backlash. Toppenish Mayor Fred Mutch testified about a non-Indian farmer living on the reservation who was upset after the Yakima filed a suit claiming all rights to water that flowed on the reservation. The farmer had to borrow money to dig his own well and Mutch remembered him exclaiming, “to hell with the Indians.”27 Mutch feared that as more situations arose the anti-Indian sentiment on reservations would escalate. Another witness, Yakima County Commissioner Charles Rich, explained how Yakima County officers and the tribal government were working together on improving relations and overcoming the animosity between county officials and the tribe. While there was still a ways to go, Rich felt they were making some progress.

After a recess, the Commission reconvened in the afternoon and heard testimony from both tribal and non-tribal law enforcement officers in the Yakima Valley. The officers testified about how they were dealing with Indians committing crimes off the reservation and non-Indians committing crimes on it. Of all the groups to testify over the two days of hearings, the law enforcement group was perhaps the most positive in its appraisal of the state of Indian/non-Indian relations and the prospect for cooperation. Both sectors of law enforcement were cross-deputized, meaning that each could arrest anyone who committed a crime in its jurisdiction. Cross-deputizaton helped keep law and order functioning on and off the reservation, which promoted good relations between both tribal and non-tribal governments.

The witnesses for the fifth group of the day were from the Olympic Peninsula and included representatives of the Makah and Lower Elwah Tribes and officials of Clallam County. The animosity between Indians and non-Indians was much more intense than in the Yakima Valley, largely as a result of the fishing issue being more prominent on the Peninsula than inland. Issues addressed included Indian poverty, how the social welfare systems worked with the tribes, and the history of fishing among the tribes, but the testimony centered on white/Indian racial relations. After the Boldt decision, Indians living on the Peninsula were victims of overt hostility. Patty Elofson, chairwoman for the Lower Elwha Tribe recounted how her younger brothers overheard fellow students at their high school speaking of “those damn Indians” when talking about the Boldt decision. This sentiment was supported by Edith Hottowe, Vice Chairwoman of the Makah Tribe: “They’re out in the open with their remarks and attitude, and it is something that is kind of difficult to define; but you sure feel it and smell it, and it doesn’t smell good.”28Clallam County Commissioner Mike Doherty felt the best way to mitigate prejudice would be joint ventures in the utilization of the Peninsula’s natural resources, coupled with educating the non-Indian populace on Native American regional history.

Once the witnesses from the Olympic Peninsula concluded their testimony, the focus of the Commission shifted northward to Whatcom County and the Lummi Reservation. Of all the counties and reservations surveyed on the day, this area was the hot-bed of antagonism. Commissioners heard testimony from Indian witnesses concerning a Ferndale elementary teacher who kicked a Lummi 6th grade student; Ferndale High School student Lilian Phare also reported that an elementary teacher told her younger sister’s class that Indians were made from clamshells that whites had thrown in the water. Testimony also focused on the animosity between the tribe and the Lummi Property Owners Association. Indian witnesses protested the fact that, like the Yakima Nation, sixty to seventy percent of reservation land was owned by non-Indians. For their part, Property Owners Association members claimed they didn’t know they were buying land on the reservation and complained that Native Americans did not pay real estate or other taxes. Additional testimony was provided by Whatcom County officials who were concerned that the county would have to provide tax-based public services like roads, libraries, and fire services to non-tax-paying Indians on the reservation.

Fishing was also a pressing issue among the Lummi. Forest Kinley, Director of Fisheries, testified that it was not uncommon for white fisherman to fish in a particular area and when the Lummi went to fish in the same area, the State closed it. Kinley continued with another prime example of unfair practices by the Fisheries Department:

Just last week, one of the State employees called me and said that we’re going to request that you close Bellingham Bay to Indians because you have caught your share of the fish, and I laughed. I thought, well, gee, that is funny, coming from the State. When they catch their share, they never close down, that they can’t do it because it is against State law. When it’s the Indians’ side, right now we have got to close down.29

Clearly frustrated by the day’s testimony, Sam Cagey, Chairman of the Lummi Business Council, vented, “I would hope that if I had the money I would be able to go and buy Slade Gorton’s land without his permission and Terry Unger and see how they like it.”30 This session revealed that there were many angry feelings on both sides of the issues in Whatcom County and that achieving resolutions would be a difficult struggle.

The final witnesses of the day were representatives from the three largest urban areas of the state: Seattle, Tacoma, and Spokane. Witnesses spoke of the challenges this diverse group of Indians faced, challenges that were both distinct from and similar to the Native Americans in rural settings. In Tacoma, reported incidents of harassment increased three fold after the Boldt decision. Adding to these incidents was an outlandish rate of unemployment. Out of a total Tacoma Indian population of 7,000, fifty-seven percent were unemployed.

Although discrimination and unemployment were common on reservations as well as in cities, isolation was one of the unique issues that urban Indians faced. The Indians in the cities came from different tribes from all across the nation. They often didn’t have a common place to meet and kinship ties had been severed, unlike the reservation Indians who could go to their tribal counsel and lived close by their families. Witnesses testified to the difficulty of keeping in touch with other urban Indians so that they did not feel isolated and get lost in the cracks of the system. After this group completed its testimony the hearing adjourned for the day.

The hearing reconvened Thursday morning, October 20, 1977. Throughout the day a recurring theme emerged: the effects of “white backlash,” especially over Indian fishing rights in the port areas of the state. The backlash took various forms, from verbal harassment and physical abuse to unfair practices by the State Fisheries Department. According to Bruce Jim of the United Columbia River Fishermen, the problems with the State Fisheries Department were not confined to the Lummi:

Washington State game officials have attacked myself striking one of my associates over the head with a shotgun, seizing our fish but making no arrests or citations for violation of the law. We were told that it was the white man’s territory and that Indians were not allowed in that vicinity of the Columbia River.31

Witnesses criticized the National Marine Fishery Services as well. According to the Executive Director of the Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission, James Heckman, “[t]he National Marine Fishery Services misrepresented the catch showing the Indians catching a much larger share than they actually caught, and obviously blaming Indians and the Boldt decision for creating some kind of economic distress for Indian People.”32

The right to fish was the dominant topic of the hearing on both days. Nisqually tribe member and Chairman of the Northwest Indian Fish Commission Billy Frank, Jr. and Councilman for the Yakima Indian Reservation Russell Jim defended their Native American birthright; they explained the cultural and historical significance of fishing for Indian communities. To Native Americans, fishing was more than just gainful employment or food on the table; it was intricately woven into their cultural and religious systems.

University of Washington Law Professor Ralph Johnson suggested that the anti-Indian sentiment was the end result of a fundamental lack of understanding of Native American treaty rights coupled with the misconception that the Native Americans were catching all the fish—thus depleting the fish runs. Professor Johnson, who founded the Native American Law Center at the UW and whose work helped lay the foundation for the Boldt decision, stated that the treaties Native Americans signed with the United States government explicitly promised them unfettered access to their traditional fishing grounds.33 He testified that Native American fishing rights should not be politicized, “where a majority of citizens can tyrannize a minority.”34 Rather, the issue should be handled in the courts, where they had already been reviewed and upheld. Johnson continued by arguing against HR 9054, which would have abrogated Indian treaties, and refuted the notion that Indian fishing rights endowed them with privileged status in relation to white Americans: “widespread backlash feeling against Indian people … appalls me because we talk about Indians being supercitizens and I would like to find a number of supercitizens that were so impoverished.”35

After Professor Johnson’s panel finished testifying, the Commission heard a statement from John Hough, who was a member of the Washington State Fisheries Task Force. Hough requested that the Commission postpone his testimony so that the task force could have extra time to complete its report. The Commission agreed and then opened the floor to fifteen individuals who wanted to make a statement, limiting each person to five minutes. Once these individuals completed what they had to say the hearing concluded. With so many relevant issues unresolved, the Commission promised to return to Seattle to hear more testimony in the future. The Commission did return on August 25, 1978 and took additionally testimony on the fishing issues. In September 1980, the Commission published it findings from Seattle and other hearings across the country. The American Indian Civil Rights Handbookoutlined the comprehensive rights that are guaranteed to every Native American and advised natives where to go if any of these rights were denied.

Local newspaper coverage was minimal in comparison to coverage of non-Indian fishermen trying to overturn the Boldt decision. However, articles and editorials did appear in newspapers from Bellingham in the north to Tacoma in the south.36 The overwhelming majority of articles were supportive of the Native Americans’ position. In fact, one Seattle Times article, commenting on the hostility between the Commission and Slade Gorton, specifically singled out Gorton for criticism: “Attorney General Slade Gorton, among the first witnesses, asked immediately, ‘Why are we here?’ and ‘Why are you here?’ “Said Gorton: ‘It is not reasonable to expect the state to accede to the demands of some of the Indians of this state.”37 Echoing the Seattle Times article, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer reprinted Gorton’s racially charged remarks, “State Attorney General Slade Gorton yesterday described American Indians to the United States Civil Rights Commission here as ‘supercitizens’ who get special privileges based on race.”38 The native periodical Indian Voice also commented on how Gorton challenged the Commission as to whether it had the jurisdiction to meddle in Washington State’s Indian affairs. In addition, _Indian Voice_described how Commissioner Frankie Freeman chastised Gorton and Guzzo for using the slanderous moniker “supercitizens” in reference to Native Americans.

The Tacoma News Tribune and the Bellingham Herald did not center on the upper levels of governmental conflict. Both newspapers did carry one article that mentioned part of Professor Johnson’s testimony defending Indian treaty rights. But for the News Tribune and the Herald, the bigger issue was the local one. This is illustrated by the _News Tribune_’s coverage of testimony accusing Tacoma of discrimination against the Puyallup tribe: “Local governmental entities are skeptical of the Puyallup Tribe, Miss Bennett testified, ignore it when possible, and have utilized the press and other news media to spread ‘scare stories and monster stories about us.’”39 In the Bellingham Herald it was the contention between Whatcom County and the Lummi that garnered the paper’s attention: “Non-Indians are attempting to terminate the Lummi tribe, Indian witnesses countered. [Terry] Unger said the treaty with the Lummis should be abrogated.”40 For Bellingham and Tacoma the important issues were those close to home.

The U.S. Commission on Civil Rights heard scores of stories from the many distinct – and yet in key ways very similar – groups of Native Americans in Washington State. In addition, the Commission heard from officials in various levels of state, county, and city government. It was clear that the Boldt decision was a catalyst that renewed and heightened discrimination and antagonistic feeling between non-Indians and the indigenous population. It was also apparent in some of the testimony that many of the local governing bodies harbored the same ill feelings toward the Indians. Aside from the American Indian Civil Rights Handbook, it is difficult to determine what the CCR hearing accomplished in the way of substantive results. No major policy initiatives or new legislation emerged in the aftermath of the hearing and many of the issues concerning tribal sovereignty, poverty, racism and discrimination, and Indian treaty rights remain unresolved or hotly contested. Yet the hearing served a necessary function by enabling both sides to air grievances and offer resolutions. It also signaled the continued willingness of the federal government to intervene in local civil rights struggles. Only after we understand the problems can we hope to solve them. For this reason, October 19th and 20th, 1977 proved to be very fruitful days for Native Americans in Washington State.

Copyright Laurie Johnstonbaugh (2006)

HSTAA 353 and HSTAA 499 2005

1 Rawls, James J. Chief Red Fox is Dead: A History of Native Americans Since 1945 (Orlando: Harcourt Brace & Company, 1996), 40

2 Public Law 280 was passed to solve the perceived problem of lawlessness and inadequate enforcement on Indian Reservations. Lawmakers argued that under the control of the State law enforcement would be more effective.

3 Rawls, 62

4 Nagel, Joane. American Indian Ethnic Renewal: Red Power and the Resurgence of Identity and Culture (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 217

5 Rawls, 70

6 Nagel, American Indian Ethnic Renewal, 222-223

7 Beginning in 1854, Washington’s Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens actively pursued and signed treaties with various tribes of Northwest Indians. One chief provision of the treaties was a clause guaranteeing Natives the right to hunt and fish in their “usual and accustomed” places. Native Americans, who did not share Euro American notions of property ownership, interpreted the treaties as meaning they could fish anywhere in their former territory. Judge Boldt determined the verbiage used in the Stevens treaties of the 1850s, “usual and accustomed” places, meant one “in common with all citizens of the territory.”

9 Frye, Jocelyn C., Robert S. Gerber, Robert H. Pees, and Arthur W. Richardson, “The Rise and Fall of the United States Commission on Civil Rights,” Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review 22 (1987): 449-505. 11 Oct. 2005.

10 “Mission,” U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, 6 Oct. 2005. 11 Oct. 2005 http://www.usccr.gov/.

11 Flemming’s career began in 1939 when he was appointed to the U.S. Civil Service Commission by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. He was president of the University of Oregon from 1961-1968 and was appointed as Chairman of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights in 1974. In 1981, Flemming was removed from the Commission by President Ronald Reagan for criticism of the Reagan administration’s attempts to roll back civil rights gains the Commission had achieved. Dr. Flemming’s career spanned 70 years and in 1994 he was awarded the Medal of Freedom by President Bill Clinton.

12 Exhibits, 1

13 Frankie M. Freeman was the first woman appointed to the Commission on Civil Rights in 1964. She served on the Commission for sixteen years. She is an accomplished attorney who has practiced law for over fifty years.

14 Zell testimony, 6-8

15 Guzzo testimony, 13

16 Guzzo testimony, 13

17 Gorton testimony, 14

18 Freeman testimony, 25

19 Gorton testimony, 25

20 Gorton began his public service in 1959 when he was elected to the Washington State House of Representatives; this post lasted until 1969. From there he served as the Washington State Attorney General from 1969-1981. He ended his career as a United States Senator for Washington State from 1981-1987 and then again from 1989-2001.

21 Indian Voice, October 1977

22 Gorton’s notoriety as an Indian opponent continues to this day. In 2000, the online Investigative Reporters and Editors, Inc. (IRE) posted an article written about Gorton and his adversarial relationship with the Indians. The article was headlined “The Last Indian Fighter” and called Gorton “American Indian’s Public Enemy No. 1.”

23 Tonasket testimony, 35

24 De La Cruz was a trailblazer in reclaiming Native American rights. He was an active participant in many local, state, and national Native American organizations, including chairing the Washington State Conference of Tribal Governments and serving as president of the National Tribal Chairmen’s Association. Eulogizing De La Cruz at his 2000 funeral, former Washington State Governor Gary Locke said De La Cruz “will always be a part of Washington State, just as this land will always be a part of him.” De La Cruz filled such a significant role in Native American politics that Evergreen College in Olympia, WA established a coarse on his accomplishments — Contemporary People/Joe De La Cruz.

25 De La Cruz testimony, 40

26 Whitebear was a founding member of the United Indians of All Tribes Foundation. He gained national notoriety and acclaim in 1970 when he led an Indian invasion and occupation of Fort Lawton in Seattle’s Discovery Park. The invasion ultimately resulted in the construction of the Daybreak Star Center

27 Mutch testimony, 62

28 Hottowe testimony, 91

29 Kinley testimony, 130

30 Cagey testimony, 123; Terry Unger was the Whatcom County Commissioner at the time of the hearing.

31 Jim testimony, 281

32 Heckman testimony, 225

33 University of Oregon News Release, June 10, 1998

34 Johnson testimony, 245

35 Johnson testimony, 245

36 There were only 11 articles that I found out of the five newspapers I researched. The newspapers I reviewed were: The Bellingham Herald, The Seattle PI, The Seattle Times, The Tacoma News Tribune, and Indian Voice.

37 Seattle Times, 10/19/1977

38 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 10/20/1977

39 Tacoma News Tribune, 10/20/1977

40 Bellingham Herald, 10/20/1977