The phone suddenly rang in the middle of the night at the home of a reporter for the Helix, a Seattle alternative newspaper, on March 15, 1970. The call was from an organizer from a Seattle Indian activist group known as the United Indians of All Tribes (UIAT), who instructed the Helix reporter to come immediately to a secret meeting place.1 Upon their arrival, the reporter and other news staff found nearly a hundred American Indians from all walks of life assembled at a Seattle home. The reporters were about to witness the second “occupation” of Fort Lawton, part of a series of UIAT demonstrations to reclaim the soon-to-be surplus military grounds for use as a cultural and social service center for American Indians. They followed along as the group snuck along private beachfront properties and over to a hill leading up to the fort. Around 6:30 a.m., the Indians quickly moved onto the Fort grounds, and built a small teepee and a fire to warm them. “Full of high spirits, the Indians dance and chant to celebrate their victory,” Helix reported. However, around 7:15 a.m., they were discovered by a patrol and soon, 50 military police arrived and demanded their surrender.

The Helix reporter observed that despite the Indians’ “defeat” at the fort, “People are becoming more aware of the validity of the Indians’ claim for recognition.” In fact, this three-week series of demonstrations by the UIAT, with Colville Bernie Whitebear and Puyallup Bob Satiacum as their leaders and spokesmen, created a media buzz in the local, national, and international press. The media coverage of this new, militant, intertribal Indian movement not only informed the public about the fort land takeover, but also the struggles and challenges faced by urban Indians, such as poverty, disease, poor education, and lack of job opportunities. The extensive press coverage helped give the UIAT the publicity, public support, and leverage they needed to negotiate with the city to reclaim Fort Lawton for what would become the Daybreak Star Cultural Center.

This essay will examine the press coverage of the UIAT demonstrations at Fort Lawton, controversies surrounding the events, and how American Indian activists used the expanding press attention and public sympathy to increase public consciousness of their needs. Local mainstream newspapers such as the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer provided expansive, in-depth coverage, which was highly informative but sometimes unsympathetic, and often contained language that reinforced stereotypes. College and alternative newspapers such as the _Helix_and the University of Washington Daily were supportive of the UIAT and encouraged Seattle residents to get involved. The American Indian press, which was rapidly growing at the time, was split over the issue; some American Indians chose not be associated with the militant tactics of the new Red Power movement. These differences were important, but the sheer volume of press attention was the most significant development. This explosion of media coverage of American Indians was part of a change of journalistic style and treatment of American Indians of the press. American Indian activists were making headlines, voicing their concerns and opinions through the press, and reaching a broad, mainstream audience in the United States and around the world.

Although there were over 4,000 American Indian residents in Seattle in 1970, they remained an “invisible” part of the population. Seattle Indians were geographically dispersed throughout the city, unlike Asian and African Americans whose populations were concentrated in the International and Central Districts, respectively. Federal government agencies such as the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and Indian Health Services (IHS) only recognized American Indians who lived on reservations, and did not direct any resources to help urban Indians.2 Many Seattle Indians felt that federal programs and funding were disproportionately going to the African-Americans in the Central District.

The American Indian Women’s Service League, established in 1958, was the first American Indian-run organization in Seattle dedicated to providing social services to urban Indians. Although the AIWSL did manage to help thousands of local Indians navigate their way through the challenges of their urban surroundings, their Seattle Indian Center operated out of a small, rented space, and relied upon private donations. Seattle Indians lobbied and voiced their concerns to the local and federal governments, but the government and the BIA continued to drag their feet on the issues. For example, Bernie Whitebear had previously proposed a new Indian Center on the Fort Lawton grounds.3 He believed the government had not taken his request seriously.4

By the late 1960s, many American Indians had grown weary of the government’s lack of response to their petitions, lobbying, lawsuits, and other attempts to work within the system. Inspired by the success of the more militant Black Power movement, American Indians began to take direct action. In 1969, American Indian activists in California occupied Alcatraz Island, formerly a federal prison, reclaiming it for their own and demanding a cultural facility on the rock. While they were unsuccessful in gaining permanent ownership of the island, the demonstration attracted a whirlwind of international media attention, and inspired other “Red Power” activists in other parts of the country.5 With the struggles and challenges facing American Indians publicized in the media, as well as a general increase in social consciousness of the time, public sentiment was turning in favor of American Indians, who could now use this as a strategy to advance their agenda.

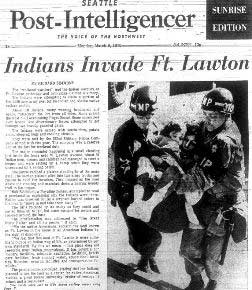

On March 8, 1970, a week before the Helix reporter accompanied the demonstration, Colville Bernie Whitebear and dozens of other American Indian activists and their families, who came to be known as the United Indians of All Tribes, entered and peacefully occupied Fort Lawton. Their goal was to reclaim the surplus land for the American Indians, which they believed was legally and morally theirs. They wanted to build a permanent cultural and social service center to help urban Indians become self-sufficient and successful, and also celebrate their cultures and traditions. Over the next several weeks, the UIAT led two more occupations of the fort, an around-the-clock picket outside the fort grounds, and demonstrations in front of the United States Courthouse to protest the activists’ arrests and alleged military police brutality.

Immediately, the local press was at the scene. The Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the two largest mainstream Seattle newspapers, covered the demonstration extensively. Both publications gave regular updates throughout the next several weeks of the demonstration, as well as developments in the UIAT’s subsequent negotiations with the government for ownership of the surplus land. They helped give American Indian activists a voice, a chance to tell the public in their own words why they were there on the fort grounds. However, each newspaper had a different “take” on the series of events.

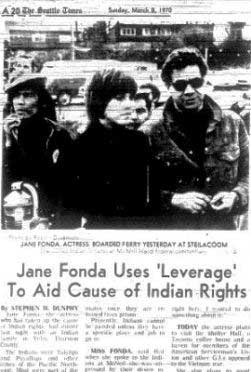

On March 9, 1970, the day after the first occupation of Fort Lawton, the front page of the Seattle Times detailed the experiences of actress Jane Fonda, who attended the demonstration in support of the American Indians.6 Little mention was made of the UIAT, the demonstration, and its purpose until page A11. The article mostly focused on specifics of accusations of military police violence, and the United States Courthouse demonstration the group was planning to protest the violence.7 The Seattle Times briefly explained the Fort Lawton occupation as being a result of leaders Bob Satiacum and Bernie Whitebear’s difficulties in obtaining the land through official channels to build their new Indian center. “We don’t have a chance in hell of getting it,” Whitebear told the Times. The Seattle Times consistently covered every new development during the three-week series of demonstrations, raising public awareness of the events, but the writers seemed indifferent to the underlying issues behind it, and the needs of urban Indians.

However, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer picked up where the Seattle Times fell short, and took an active interest in the UIAT’s demonstrations and its message. While the Seattle Post-Intelligencer did not profess sympathy for the cause, the news coverage expressed a deeper concern for and fascination with this new American Indian movement, and struggles facing urban Indians. The takeover of Fort Lawton dominated the headlines, pictures, and articles featured on the first two pages of the March 9 issue. On March 12, a headline read, “Equality in Seattle Is Indians’ Message.” The Post-Intelligencer acknowledged, “the city of Seattle must bring all its citizens up to the same level if it is to progress as a community.”

Through the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Bernie Whitebear informed the public about challenges facing urban Indians, such as the 37% unemployment rate among Seattle Indians, poor housing and living conditions, and illiteracy.8 Whitebear and Satiacum presented their plans for the new Indian center as a place that would not only address these problems by providing social services and education, but would also celebrate traditional American Indian cultures and educate the Seattle community.9 Satiacum said, “For the school, we want to show how proud we are of our own culture and heritage. We want to pass that along – not to just our own descendents, but to whites, too.” The leaders also planned to restore most of the land to its natural state. “There would be berries, trees, game… somewhere among the trees, we would build a true Indian longhouse to be used as school and museum,” Satiacum told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer.

In addition to the mainstream Seattle press, the Fort Lawton demonstrations naturally attracted the attention of the rapidly growing American Indian press. The reaction from the American Indian press reflected a difference in opinion between different Indian groups. The Indian Center News, a monthly newsletter published by the American Indian Women’s Service League, gently supported the demonstration. The April 1970 issue briefly covered the events of the three-week demonstration, reported the names of the activists involved, and reprinted the entire text of a UIAT “proclamation” reclaiming the land for the American Indians.10 The Service League was not a militant organization, and most of its members chose to support the occupation from behind the scenes, rather than on the front lines. The AIWSL was optimistic about the results of the demonstration; they reported that “the nonviolent invasion…accomplished the UIAT goal of bringing the plight of urban Indians to the attention of officials and the public.”

Cherokee Examiner editor N. Littlefoot Magowan, however, was an excited and passionate participant in the demonstration. The editor gave a detailed, in-depth personal account of the events that transpired on April 2, 1970 in a special report to the Los Angeles Free Press.11 After storming the gates with 30 to 40 other American Indians, Magowan described “giving the soldiers a run for their money,” and exclaimed, “I was the first member of my family in three generations to rip off an army fort. Haya-hei-hai!” After being chased by a young MP, he was finally arrested and participated in an attempted escape. Magowan ended his piece by proclaiming, “This area, this Fort, is ours in all ways…I’ll be back at Fort Lawton, possibly before the story is even printed. WE SHALL LIVE AGAIN!”

While some American Indian publications and journalists gave their full support, others were completely silent about Fort Lawton. The Indian Voice, published by the Small Tribes Organization of Western Washington in Federal Way, made no mention of the demonstration that occurred only a short geographic distance away. It is unknown specifically why the paper decided to ignore these events; however, according to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Small Tribes Organization did not endorse the Fort Lawton demonstrations.12 Perhaps they wanted to distance themselves from the untraditional, more radical tactics embraced by activists of the UIAT. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer cited the lack of endorsement as “evidence that the state’s reservation Indians were not in total sympathy with the aims and methods of their urban brothers.”

As news of the Fort Lawton occupation and urban Indian issues reached readers throughout the city, the United Indians of All Tribes gained the support of local student publications. The University Of Washington Daily concentrated on the UIAT’s perspective in the debate; reporter Francis Svensson writes, “because Indians have all too often been ‘invisible’ for purposes of health, welfare, employment, and educational services in Seattle… there has been a very real need to concentrate services and facilities in a centralized multipurpose facility.”13 The Seattle Community College publication The City Collegian featured an article titled “Ft. Lawton Indians Capture Summit,” which outlined the key points a group of American Indian guest speakers presented to college students on behalf of the UIAT.14 This article was followed by an editorial that encouraged Seattle Community College to step forward and “meet with the United Indians of All Tribes to smoke a peace pipe, and agree to meet with all others to facilitate and aid the Indians in finding and establishing an Indian University and Cultural Center.”15

The Fort Lawton occupation became a national sensation, bringing awareness of American Indian issues to readers across the country. The New York Times reported on March 9, 1970 that the “Indians ‘attacked’ Fort Lawton at its main gates, set up diversionary actions, scaled bluffs and fences and managed to put up a teepee in the small clearing in some woods.”16 In a related article, New York Times writer James Naughton acknowledged the American Indians’ plight, bringing national attention to the problems urban Indians were facing.17 He explored a number of issues, such as poor education and healthcare, and difficulties accessing welfare and other social services outside the reservation. He wrote, “they are smothered with federal paternalism alternating with malignant neglect.”18

Washington Post reporters were fascinated by the American Indian activists’ new direct-action tactics. Staff writer William Greider wrote that while many American Indians are uncomfortable with having to take such extreme measures, they felt that high-profile demonstrations were the only way to get results. He described the demonstrations at Alcatraz and Fort Lawton as a reflection of two national issues: “One is the growing concentration of Indian migrants in the cities and the problems they face in adjustment…The other issue–job discrimination against Indians by the Bureau [of Indian Affairs] itself.”19

The national attention the Fort Lawton demonstration received, as well as other Indian demonstrations and movements sparked by Alcatraz, pushed the Indians’ cause all the way to the White House. In July 1970, the New York Times described a “pledge” by President Nixon promising federal help for American Indians’ social service programs and Indian centers, as well as land rights.20 While this “pledge” was mostly symbolic and had little funding to back it up, it was considered a step in the right direction by a number of American Indian leaders. However, the Washington Post reported that President Nixon’s “promise” later came under criticism by Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy.21 Speaking at an Indian conference, Kennedy called for increasing Indian participation in the BIA, and improving national policies to better serve the American Indian population.

The occupation also captured the attention and fascination of the world press. The Seattle Times, while dismissing the occupation as “only a demonstration with a teepee set up on a pleasant, sleepy military reservation,” humorously discussed how this event was a fascinating story in Europe.22 A representative of the Italian News Agency inquired, “Tell me, do you have an Indian problem out there? …Is it true you have 12,000 Indians living in your city?” A reporter from the London Daily Express wanted to know if Jane Fonda had been handled roughly, instructing the _Seattle Times_reporter to call him if she said anything new. The Times of London described the occupation as being part of the “Red Power” movement which was gaining momentum during a “lull in the noise of the Negro protest in the United States.”23

The expansive media coverage of the demonstrations at Fort Lawton signaled a shift in the treatment of American Indians in the press. In her book, Native Americans in the News: Images of Indians in the Twentieth Century Press, Mary Ann Weston describes an overall change in journalistic style, as well as changes in the coverage of American Indians from the 1950s to the 1970s.24 The 1950s was the era of “termination,” the US government policy to end its relationship with and recognition of tribal governments, and assimilate American Indians into white society. Weston wrote that journalists either reported about “good Indians” who appeared to reject their traditional cultures and assimilate into mainstream white society, or “degraded Indians,” a poverty stricken people who were lazy, alcoholic, or victims of unfortunate circumstances. The journalists reported the stories in a style which relied on hard facts from official sources. The news articles did not describe or characterize American Indians or “get at the realities of native lives and cultures.”25

In the late 1960s, the rhetoric and policies began to change from termination to “self-determination,” a movement in favor of the Indians taking control of their lives, institutions, and celebrating their cultures. The news reporting style of that time became highly descriptive, interpretive, and investigative, delving deeper into American Indian issues and including their voices and opinions in the coverage. For the first time, American Indian news stories were initiated and told by the American Indians themselves.26 The Fort Lawton demonstration is an example of this; it was a UIAT-planned event designed to attract the attention of the community and the press. Bernie Whitebear and Bob Satiacum told their side of the story and were quoted extensively in mainstream newspapers.

With the rise of American Indian activism, many new American Indian publications sprung up in the 1960s and 1970s, providing a platform for American Indian journalists to start their careers and report the news from an Indian point of view. Locally, the Indian Center News, initially a small weekly newsletter, expanded into a full-length newspaper with extensive coverage of American Indian affairs. On the national level, many new American Indian papers were founded, from Indian Voices in Chicago to Wassaja in San Francisco. The American Indian Press Association, founded in 1970, distributed news to over 150 Indian publications. Each month, the Mohawk paper Akwesasne Notes reprinted an extensive collection of American Indian-related news clippings from mainstream, underground, and American Indian papers throughout the country. These papers captured a wide American Indian audience, providing coverage of tribal and urban Indians news as well as broader issues affecting Indians.27

Despite the increased visibility of American Indians in the press, mainstream newspapers often still took a paternalistic or dismissive tone towards American Indians, and used language that perpetuated stereotypes. The mainstream Seattle press cast the Seattle Indian activists in the mold of the age-old “noble savage” stereotype, portraying them as proud, noble Indian “warriors.” On March 9, 1970 the Seattle Post-Intelligencer began their coverage of the demonstration by writing, “the ‘weekend warriors’ met the Indian warriors at Fort Lawton,” playfully describing the event as a clash between white and American Indian “warriors”, as opposed to a clash between military police and peaceful protesters.28 Seattle Post-Intelligencer political writer Shelby Scates described Bernie Whitebear as having “the compact build of a middleweight fighter.”29 Another Seattle Post-Intelligencer writer, Hilda Bryant, refers to one picketer outside the fort as a “Sioux brave from Saskatchewan.”30

According to the March 10, 1970 article in the Seattle Times, “Indians Drum up Support for Fort Claim,” American Indian demonstrators were playing drums while picketing the courthouse.31 Reporters Don Hannula and Jerry Bergsman described the drums as “war drums.” The idea that the drums were “war drums” presents the protesters as stereotypical Indian warriors, when perhaps the drums may have been part of other tribal ceremonies or traditions.

In the same article, the Seattle Times painted a romanticized picture of the demonstration, reporting that “the invasion had some aspects of an old Western movie. The Indians scaled the steep, western face of Magnolia Bluff to gain entrance to the fort’s grounds.” A bold headline in the Seattle Post-Intelligencer read, “MP Now Knows ‘How Custer Felt.’”32 Writer Hilda Bryant quoted an Army guard who associated this event with the 1876 Battle of Little Bighorn, in which Colonel Custer’s troops were greatly outnumbered and defeated by the Sioux.33 Bryant wrote of the activists, “About 100 of them, viewed as radicals by an alarmed white citizenry and as renegades by embarrassed reservation tribes, stormed the fort in what must have seemed to military police like a rerun of Custer’s Last Stand.”34 The Seattle Times referred to the ordeal as the “Battle of Fort Lawton.”35

Equating the Fort Lawton demonstrations with wars and battles, the mainstream press referred to the occupation as an “invasion” or “attack,” although the papers occasionally acknowledged it was a peaceful demonstration. Both the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer used words such as “invasion,” “attack,” or “seize” to describe the UIAT’s actions in many articles. Maribeth Morris of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer wrote, “An ‘attack force’ of nearly a 100 Indians stormed Fort Lawton yesterday in the two-pronged offensive that landed most of the invaders in the post stockade.”36 Seattle Post-Intelligencer reporter Richard Simmons wrote, “About 100 Indians, many wearing headbands and beads, ‘attacked’ the fort from all sides…The Indians were armed with sandwiches, potato chips, sleeping bags, and cooking utensils.”37 Use of words such as “invasion” also plants the idea that these activists were “warriors” on the attack into the imaginations of readers. In contrast, UIAT leader Bernie Whitebear characterized the occupation as a modern, militant movement; while he described the occupation as an “invasion,” he described the UIAT’s tactics as a “pattern of urban guerrilla warfare.”38

Stephen Cornell writes in his book, The Return of the Native, “Indians play a central and heroic – if doomed – role in the popular romance of America’s past.”39 The mainstream press portrayal of the American Indian activists was reminiscent of much of white America’s perceptions of American Indians in real and fictionalized 19th-century wars. This portrayal of the United Indians of All Tribes as noble Indian warriors misrepresented them as a group of uncivilized people “attacking” the fort. Well over a hundred years ago, more than 250 of Custer’s soldiers did, in fact, die in the Battle of Little Bighorn; in the Fort Lawton demonstration, however, it was the American Indians who were said to have been brutalized. As opposed to being “warriors,” The UIAT was a group of highly articulate, informed, and in many cases, college-educated activists who wanted to peaceably reclaim the land they believed was rightfully theirs.

The local papers also used the word “powwow” to describe meetings and conversations. On March 16, the Seattle Times used the word “powwow” to describe the negotiation American Indian leaders were demanding to have with President Nixon.40 On March 1, as Senator Henry Jackson toured Fort Lawton, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer described his meeting with the local Kinechtapi Indian Council as a “powwow.”41 The Post-Intelligencer also referred to a demonstration at the courthouse as a “powwow.” 42 In reality, “powwow” is the Algonquin word for an intertribal social gathering featuring traditional American Indian arts and crafts, music, and dancing.43 Describing serious meetings, negotiations, and protests that could possibly determine the future of many American Indians as “powwows” likens their importance and significance to that of a social event.

By appropriating words such as “powwow,” and portraying the UIAT as proud, noble Indian “warriors” who “attacked” the fort, the mainstream press perpetuated stereotypes of American Indians, yet at the same time, appealed to the emotions of the public. Many white Americans, often in a misguided fashion, admired these “positive” stereotypes, and attempted to blend their idea of American Indian culture with their own. They staged their own “powwows,” collected and produced “Indian” arts and crafts, and appropriated American Indian spirituality.44 It also became fashionable among people of the late 1960s and early 1970s counterculture to wear American Indian jewelry and clothing.45 Philip Deloria suggested in his book, Playing Indian, that American Indian activists deliberately used this sort of “cultural power” to their advantage. He wrote that the Red Power activists “were not engaging in simply military or revolutionary actions. Above all, they were committing cultural acts in which they sought social and political power through a complicated play of white guilt, nostalgia, and the deeply rooted desire to be Indian…”46

Sentimental, sympathetic feelings towards American Indians based on stereotypes are apparent in some of the letters written by concerned citizens to local and state officials. In a letter to Governor Daniel Evans, John LaMonier of Loon Lake, Washington, implored the governor to help “this great and courageous Chief Bernie Whitebear” regain the Fort Lawton lands.47 “Surely you can see after watching the many movies showing the Cowboys and Indians, where the Cowboys had guns and bullets, whereas the poor Indians only had bows and arrows to try to protect the land they loved…” LaMonier wrote. Seattle area resident William Matchett wrote a letter in support of the UIAT to Mayor Wes Uhlman on behalf of the local Religious Society of Friends organization, noting “the Indian heritage of knowledge of man’s relationship to his natural environment is basic to all men.”48 This sort of public sentiment, however misguided, worked in favor of groups such as the UIAT. Stephen Cornell wrote that American Indians effectively took advantage of this public sentiment and receptivity to force their concerns into public consciousness.49

The Fort Lawton demonstrations, while bringing public awareness to the American Indian activists cause, also sparked controversies such as alleged police brutality during the occupations. The mainstream Seattle press was wary of reports of accusations of military police brutality towards the demonstrators. The American Indians alleged on many occasions that demonstrators were beaten, injured, and poorly treated by the military police guards at Fort Lawton. For example, according to the Seattle Times, at the April 2, 1970 demonstration, Indians alleged that the military police had used tear gas and tracker dogs.50 Neither the Seattle Times nor the Seattle Post-Intelligencer followed up on these reports, nor did they investigate the validity of these claims. It was not reported whether any charges were filed, or what the results an internal the investigation by the military police may or may not have turned up.

The mainstream press based its assessment of the violence on its own observations. On March 9, the _Seattle Post-Intelligencer_reported that the MPs were fully equipped with riot gear, and had chosen to march the prisoners through a blackberry patch rather than on the road. Despite the rough handling, the paper reported that there was only a single instance of violence in which a young Indian was shoved up against a desk.51 However, the press was quickly barred from the premises, and while the Seattle Post-Intelligencer did manage to get a brief glance at the chaotic situation inside the jail, they were soon asked to leave.

The mainstream press also looked to Army spokesmen to give their side of the story. The Army repeatedly denied any wrongdoing. Colonel Palos, the commander in charge of the fort, countered the Indians’ accusations with allegations of his own. He told the Seattle Times that Indians used chains and threw objects to resist arrest and that two MPs were injured by Indians.52 He also said that two Indians were seen near a building which had caught fire and caused up to $500 worth of damage, implying that those two people were the ones who had set the fire. Though none of these charges could be confirmed (for instance, the two MPs were injured in a car accident, not by Indians), Palos remarked that the fire incident “will hurt the public image of the Indians.”

A Seattle alternative paper, the Helix, on the other hand, vividly described violence at the March 8, 1970 demonstration at Fort Lawton. According to the March 20 article “Geronimo’s Revenge,” American Indians were chased down by military police with nightsticks, resulting in ten men being badly beaten.53 The _Helix_also reported that the demonstrators were treated with unnecessary roughness during the March 15 occupation. The military police forcibly hauled them off to an overcrowded military jail, where “52 men were crowded into a small 12 foot by 14 foot cell.”

The Helix reporter had disdain for the military police and their commander, Colonel Palos, who was portrayed as a harsh authoritarian who straightened up nicely when he came into public view. During the chaos, a teenage boy had been forced up against the fence by an MP, and then escaped and ran off the property. Colonel Palos shouted, “GET HIM,” and they pursued and captured the boy even though he was no longer on federal property. When Colonel Palos was confronted by the press, however, the Helix reporter noted, “I have never seen someone become reasonable and mature faster in my life. Full of understanding and wisdom. Even a little story for the press.”

The University of Washington Daily also gave a detailed account of the alleged rough treatment and violence. The publication gave student Lee Brown, a Chickanauga Cherokee, a chance to tell his personal account: “’There were 46 persons in our cell… they let women and children go first, then the married couples…But there were about 10 single males left, and when they were alone, they were beaten.’”54 Brown said that 10 Indians were hospitalized afterwards, and Bernie Whitebear received “severe contusions on the left arm.” Later, twenty university students participated in the picketing of the federal courthouse and Fort Lawton to protest the violence. Although the University of Washington Daily reported that the army claimed that there was no evidence of brutality, Brown got the final word: “’there has been a definite attempt by white society to destroy the Indian society, and we have been dying by assimilation.’”

The media spotlight shined brightly on Hollywood actress Jane Fonda, who hoped her presence at the Fort Lawton demonstration on March 8 would prevent military police violence against the Indians through the media attention she would attract. She also participated in a subsequent courthouse demonstration against the alleged rough treatment by the military police. According to the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Fonda said, “I thought that my presence there might decrease the likelihood of brutality against the Indians who had planned to enter the base.”55 Both the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer continually reported on her activities and featured her picture in a number of articles. As mentioned earlier, on March 9, the first mention of Fort Lawton in the Seattle Times was in an article about Jane Fonda on the front page.56

Jane Fonda’s presence, however, did little to quell the chaos that ensued between the military police and the American Indians during the occupation. “Evidently the military police wanted no witnesses,” she told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer after being forcibly removed from Fort Lawton. Fonda also went to talk to some soldiers at Fort Lewis, and was subsequently arrested and banned from returning to either of the military installations. Fonda made the news in the Seattle Times and the Seattle Post-Intelligencer again on March 16 and March 17, respectively, after she rallied with a group of 100 American Indians outside the United States Courthouse before the arraignment of 10 Fort Lawton demonstrators charged with trespassing.57

A writer for the Helix credited as “Roger” gave his opinion on the matter: “…she attracted a lot of attention to herself and blurred the issue.”58 According to Roger, the dominating story on local television was “’Jane Fonda Ejected from Fort Lawton’ with the Indians forming a picturesque background.” She was asked by the local media whether she was there in order to gain publicity for herself, rather than the Indian movement. Fonda told reporters, “This kind of publicity is doing me nothing but harm… I could very well lose the Oscar because of this.”59

Fonda was later credited by many for initially helping to bring such widespread media attention to the American Indian demonstration at Fort Lawton. In 1994, Bernie Whitebear wrote, “the support and presence of Jane Fonda gave the invasion and occupation worldwide attention, and captured the imagination of the world press…Without really appreciating it at the time, the Indian movement has achieved through Jane Fonda’s presence, a long-sought credibility that would have not been possible otherwise.”60In his autobiographical book, Humbows, Not Hotdogs! Memoirs of a savvy Asian American Activist, Filipino-American activist Bob Santos also remembers how Jane Fonda’s celebrity attracted attention to his friend Bernie Whitebear’s cause.61 The Times of London also attributed the publicity of the incident to Jane Fonda’s presence at Fort Lawton in the March 11, 1970 article, “First and Last Americans.”62

Although it seemed the overall awareness of the press and the support of public were growing, not everybody agreed with the UIAT’s objective to reclaim the land to build a cultural and social service center. The American Indian activists were seen by many as a nuisance, and a barrier to some Seattle residents’ dreams of a sprawling new city park. In December 1970, Seattle Times columnist Herb Robinson described the Indian occupation of the fort as “only the latest in a lengthy series of distractions which have threatened to obstruct acquisition” of the surplus acreage, and as “the most difficult hurdle” to park proponents’ success. He wrote that it would be “a tragedy of profound proportions” for Seattle not to build the park. While acknowledging that Indians need and deserve a place to provide social services, he argued that the Indians could just as easily provide those services from another site in the city, on land less valuable than the Fort Lawton grounds.

Others argued that the Indians were already entitled to the land on the reservations, and that giving them more land would not solve the problem. An editorial from the Bremerton Sun described the Indians’ actions at Fort Lawton as “bordering on the ludicrous at least if not the bizarre,” and “something out of an old ‘B’ movie.”63 The editorial continued, “It might behoove some of those Indians making so much noise about a cultural center to go home and improve those reservations,” which the editorial claimed were full of garbage, deserted homes, and rusted cars. The _Bremerton Sun_suggested that Fort Lawton would be degraded to that condition if turned over to the Indians. The editorial did not address the fact that thousands of Indians, displaced from their tribal lands and then their reservations, came to call the city of Seattle their home and live in its many neighborhoods.

The press also pointed out the lack of support from the local and national government. The Seattle Times reported that Senator Henry “Scoop” Jackson, chairman of the Senate Interior Committee, said, “I strongly believe that this particular urban site would be better suited for a city park.”64 Louis R. Bruce, Commissioner of Indian Affairs, said that while the BIA was not necessarily opposed to the occupations springing up around the country, the Bureau could not assume responsibility for Indians living outside their reservations.65 Bernie Whitebear told the Seattle Times this lack of BIA intervention was a result of “an unethical, political power play,” by Senator Jackson, and alleged that Jackson had pressured Bruce to stay out of the fight between Seattle and the Indians.

Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman sided with the senator. He told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer that he wanted the surplus land to be taken over by the city of Seattle to build one of the most beautiful city parks in the region.66 Rather than give the UIAT any of the land, he offered to give them input into how the city park would be developed. Other city officials were equally unsupportive, and suggested that the UIAT should build their cultural center on one of their reservations. Seattle Park Board member Donald Voorhees told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “I am afraid that the ultimate result of the Indians’ activities may be to torpedo the [Senate] bill for releasing the lands and then no one will he be able to use it.”67 Voorhees said that the city only would have only 409 acres on which to build a park, when the Indians, such as the Yakima Tribes, have millions of acres of reservation land on which they could build their cultural facilities.

Bernie Whitebear and the UIAT firmly stood their ground on the idea that the land should be returned to the Indians. Building facilities on reservations many miles away from Seattle would not meet the needs of Indians living in the city. Also, the Indians did not trust the government to give them enough autonomy to run a facility on a city-owned park. “…what difference would that be from control over us by the Bureau of Indian affairs?” Bernie Whitebear asked while speaking with the _Seattle Post-Intelligencer.68_

As news of the Fort Lawton occupation and urban Indian issues reached readers throughout the city, the United Indians of All Tribes gained support of many local organized groups. At the University of Washington, the Indian Student Association spoke out in support of the cause through the University of Washington Daily. Reporter Barb Clements wrote, “Indian students said they not only would support reoccupation forces at Fort Lawton, but would also volunteer their services for the cultural and educational activities planned on the property.”69 Clements’ article included part of the UIAT proclamation, as well as a statement issued by the Indian Student Association urging the public to actively support American Indians in their struggle to preserve their culture and to control their own destiny within the structures of American society.

In November 1970, the Medium, a Seattle African-American newsletter, reported that the Indian group had also gained the attention and support of the Seattle Humans Rights Commission. The Medium reported that “the Seattle Human Rights Commission has unanimously passed a resolution which recognized the moral right of American Indians and Alaska natives to Fort Lawton land.”70 The Seattle Human Rights Commission’s endorsement indicated increasing Seattle community support; it was one of over 40 non-Indian organizations in the area that supported the American Indian activists in the Fort Lawton occupation.71

Public sentiment was on the side of the American Indians as well. Despite the controversy with public officials and stereotypical language, the media coverage played right into the growing public sympathy for American Indians. Activism, in general, was on the rise in the 1960s and 1970s, and the public was ready and eager to listen to the perspectives of disadvantaged groups and move for change.72 Dozens of letters and petitions from around the Seattle area poured into Mayor Wes Uhlman’s office, pleading with the mayor to allow the American Indian group the land they believed was rightfully theirs.

In 1971, public pressure forced the city government to meet the UIAT Council at the bargaining table. After five months of negotiations, they finally reached an agreement to “lease” 16 acres to the American Indians for 99 years with an option to renew. Not only was this a breakthrough for the American Indian activists, who had successfully planned a three-week demonstration and captured the imagination of the media and the public, but it was also a breakthrough for the politicians involved who had previously ignored the needs of urban Indians. Senator Henry Jackson praised Bernie Whitebear for bringing the dispute to the bargaining table, and said he would support the group’s applications for federal grants to help find their new social service and cultural center, now known as Daybreak Star.73 Deputy Mayor John Chambers told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, “…[Bernie Whitebear] represented something real, not something that was going to fade away. What he showed us was that we were negotiating with a people with real thoughts and needs.” 74

The UIAT demonstrations at Fort Lawton had successfully captured the interest and imagination of the press and the public. While some opinions expressed in the newspapers were hostile or indifferent, many news articles effectively informed the public about the challenges facing urban Indians in Seattle, and sometimes called for public support. Many Seattle citizens and organizations sided with the UIAT, and successfully pressured politicians to listen to the activists’ claims and strike a compromise. In 1977, Bernie Whitebear and the UIAT’s dreams came alive, as Daybreak Star Cultural Center opened its doors to serve the Seattle community. Today, Daybreak Star Cultural Center continues to provide essential social services to over 25,000 people in the Seattle Indian community, such as the Head Start educational program for children, family counseling, and activities for seniors.75 Each year, over 10,000 people attend the center’s annual Seafair Indian Days Powwow, a celebration of American Indian arts and culture featuring drum groups, arts and crafts, and performances by several hundred dancers. 76 Bernie Whitebear, who died of cancer in 2000, became a celebrated figure in the press, which recognized the UIAT’s accomplishments and the center’s positive impact on the community. Ramona Bennett, former chairwoman of the Puyallup tribe, told Indian Country Today, “Hundreds of thousands of people knew Whitebear through the press. But when the cameras were gone, Bernie continued to work very hard. All of our little dreams…he made them reality and he administered them very responsibly.”77

C**opyright © Karen Smith 2006

**HSTAA 498 Autumn 2005

1 “Geronimo’s Revenge,” Helix, March 20, 1970.

2 Bernie Whitebear, “A Brief History of the United Indian of All Tribes Foundation,” United Indians of All Tribes Foundation web site,http://www.unitedindians.com/fondhistory.html, 1994.

3 Coll Thrush, “The Crossing Over Place: Urban and Indian Histories in Seattle,” (PhD diss., University of Washington, 2002), 316

4 Whitebear, “A Brief History of the United Indian of All Tribes Foundation.”

5 Thrush, “The Crossing Over Place,” 316

6 John Hinterberger, “Jane Fonda Gripes about Detention at Fort Lewis,” Seattle Times, March 9, 1970.

7 Jerry Bergsman and Paul Henderson, “Indians ‘Invade’ Army Posts,” Seattle Times, March 9, 1970.

8 Hilda Bryant, “On the Outside Looking Hopeful,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 22, 1970.

9 Frank Herbert, “How Indians Would Use Fort,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 22, 1970.

10 “United Indians of All Tribes Use Invasion of Fort Lawton in Effort to Get Support for All Indian Multi-Service and Educational Center,” Indian Center News, April 1970.

11 N. Littlefoot Magowan, “Indians Attack Army,” Los Angeles Free Press, reprinted in Akwesasne Notes, May 1970.

12 Bryant, “On the Outside Looking Hopeful.”

13 Francis Svensson, “Fort Lawton: a community of Indians?” University Of Washington Daily, March 12, 1971.

14 “Ft. Lawton Indians Capture Summit,” City Collegian, April 9, 1970.

15 “Indians Raped,” City Collegian, April 9, 1970.

16 “Indians Seized an Attempt to Take Over Coast Fort,” New York Times, March 9, 1970.

17 James M. Naughton. “A Pledge to Indians of a New and Better Deal,” New York Times, July 12, 1970.

18 Ibid.

19 William Greider, “Indians Find Protests Bring Results,”Washington Post, April 19, 1970.

20 Naughton, “A Pledge to Indians of a New and Better Deal.”

21 “Kennedy Scores Indian Program,” Washington Post, April 19, 1970.

22 “Indian ‘Attack’ On Fort Fascinates World Press,” Seattle Times, March 9, 1970.

23 “First and Last Americans,” The Times (London), March 11, 1970.

24 Mary Ann Weston, Native Americans in the News: Images of Indians in the 20th Century Press, (Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996), 104-106

25 Weston, Native Americans in the News, 102-103

26 Weston, Native Americans in the News, 133

27 Stephen E. Cornell, The Return of the Native: American Indian Political Resurgence, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), 138-139

28 Richard Simmons, “Indians Invade Fort Lawton,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 9, 1970.

29 Shelby Scates, “Whitebear Leads Indians to Victory in Ft. Lawton,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 5, 1971.

30 Bryant, “On the Outside Looking Hopeful.”

31 Don Hannula and Jerry Bergsman, “Indians Drum up Support for Fort Claim,” the Seattle Times, March 10, 1970.

32 Hilda Bryant. “MP Knows ‘How Custer Felt’,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 3, 1970.

33 “Battle of the Little Bighorn,” Microsoft Encarta, 2005.

34 Hilda Bryant, “Indians Build at Fort Lawton,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 25, 1976.

35 Jerry Bergsman and Dee Norton, “Indians Rally at Courthouse,”Seattle Times, March 16, 1970.

36 Maribeth Morris, “Invaders Jailed; Old Building Set Afire,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 3, 1970.

37 Simmons, “Indians Invade Fort Lawton.”

38 Whitebear, “A Brief History of the United Indian of All Tribes Foundation.”

39 Cornell, The Return of the Native, 173

40 “Indians Want Nixon Powwow,” Seattle Times, March 16, 1970.

41 “Jackson checks Lawton scene; Senator, Indian powwow,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 1, 1970.

42 “Indians Move on Fort Today,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 10, 1970.

43 “Native Americans of North America,” Microsoft Encarta, 2005.

44 Philip J. Deloria, Playing Indian, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998),128, 129, 137,167-168

45 Weston, Native Americans in the News, 129

46 Deloria, Playing Indian, 179

47 John LaMonier, letter to Governor Daniel J. Evans, June 1, 1970, Seattle Mayor box 30, folder “Fort Lawton,” University of Washington Libraries Special Collections, Allen Library basement

48 William H. Matchett, letter to Mayor Wes Uhlman, April 13, 1970, Seattle Mayor box 30, folder “Fort Lawton,” University of Washington Libraries Special Collections, Allen Library basement

49 Cornell, The Return of the Native, 173

50 Don Hannula, “The Indians and Fort Lawton: 15 Face Trespass Charges,” Seattle Times, April 3, 1970.

51 “Army Disrupts Indian Claim on Fort Lawton,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 9, 1970.

52 Hannula, “The Indians and Fort Lawton.”

53 “Geronimo’s Revenge.”

54 “Ft. Lawton MP’s Accused of Beating Indian Picketers,” University Of Washington Daily, March 11, 1970.

55 “Indians Move on Fort Today.”

56 Hinterberger, “Jane Fonda Gripes about Detention at Fort Lewis.”

57 Bergsman and Norton, “Indians Rally at Courthouse,”

“Indians Want Nixon Powwow,”

“14 Indians Arraigned for ‘Invasion’,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 17, 1970.

58 Roger, “Oh, Jane…,” Helix, March 12, 1970.

59 Jerry Bergsman. “Indians Began 2nd Week of Picketing,” Seattle Times, March 17, 1970.

60 Whitebear, “A Brief History of the United Indian of All Tribes Foundation.”

61 Bob Santos, “Humbows, Not Hotdogs! Memoirs of a savvy Asian American Activist,” (Seattle: International Examiner Press, 2002), 56

62 “First and Last Americans.”

63 “The Indian Siege of Fort Lawton,” Bremerton Sun, March 17, 1970.

64 Don Hannula, “Ft. Lawton dispute: Sen. Jackson denies ‘pressure’ on bureau,” Seattle Times, January 22, 1971.

65 “Indian Head Claims Lack of Authority,” Spokesman Review, March 26, 1970.

66 “Jackson Checks Lawton Scene,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 1, 1970.

67 Sue Hutchison, “Park on Fort Land Reaffirmed,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, April 3, 1970.

68 Bryant, “MP Knows ‘How Custer Felt’.”

69 Barb Clements, “American Indian Group Supports ‘Reoccupation’,” University Of Washington Daily, March 10, 1970.

70 “Seattle Human Rights Commission Says Claim of Indians Must Not Be Ignored,” Medium, November 12, 1970.

71 Thrush, “The Crossing Over Place,” 318.

72 Weston, Native Americans in the News, 129.

73 Hilda Bryant, “City, Indians in Accord on Lawton Center,” the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, November 15, 1971.

74 Ibid.

75 “Keeping Traditions Alive and our Future Promising,” United Indians of All Tribes Foundation web site,http://www.unitedindians.com/index.html.

“Children, Youth, and Family Services,” United Indians of All Tribes Foundation web site, http://www.unitedindians.com/fondprograms.html

76“20th Annual Seafair Indian Days Powwow,” United Indians of All Tribes Foundation web site, http://www.unitedindians.com/powwow.html

77 Cate Montana, “Tireless advocate Bernie Whitebear mourned,” Indian Country Today, August 2, 2000.