The influence of communism within the American labor movement significantly altered the course of labor history. Out of this fascinating convergence came a unique figure: the communist labor leader. Studying these men and women, much can be learned about the radicalization, internal politics, and ultimately the suppression of the labor struggle in North America.

With regard to the issue of communism and organized labor on the West Coast of the United States and into British Columbia, Canada, two figures dominated the stage: Harry Bridges and Harold Pritchett.Pritchett was the president of the International Woodworkers of America (IWA) from 1937 until 1940 while Bridges fearlessly led dockworkers as president of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU). Both men played an integral role in shaping the labor movement during the Great Depression. Pritchett and Bridges also shared an important characteristic: they were aliens, non-citizens of the United States. Both were heavily influenced by the Communist Party and formed their unions into militant protectors of labor. Both faced persecution from anti-union red-baiters who fought labor’s every move. Both faced intense scrutiny by the U.S. Government. Both were tried before the anti-communist tribunals of the time. And both faced deportation.

But while Bridges survived government attempts to deport him, Pritchett was eventually denied re-entry into the United States because of his political convictions. Harold Pritchett thus became one of the first casualties of the “second red scare” and, along with Bridges, personifies the figure of the communist labor leader on the West Coast. While Bridges’ life has been well chronicled, less is known about Harry Pritchett. This essay will follow Pritchett from his humble beginnings as a rank-and-file shingle weaver to his ouster from power as president of the IWA. Pritchett’s life provides unique insight into the lives of woodworkers and the political struggles that marked IWA history during the 1930s and 1940s.

Background: Harold Pritchett

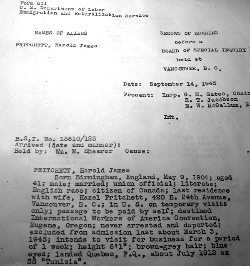

Harold Pritchett was born on May 9th, 1904 in the city of Birmingham, England, widely known for its contribution to the Industrial Revolution. Perhaps these roots destined him for a life in labor and industry.1 In 1912, at the age of eight, the Pritchett family emigrated from England to Canada aboard the SS “Tunisia” and landed in Quebec.2 From there, the family traveled to Port Moody in British Columbia, just east of Vancouver, where they settled.3 After Pritchett graduated from grade school, as a boy aged fifteen years, he began his career in the woodworking industry.

Pritchett received his first job at the Thurston-Flavelle sawmill in Port Moody, BC in 1919.4 For eleven hours a day he tended conveyors in a planer mill (which essentially processes raw timber into a usable product). His wages? Ten cents an hour.5 It was here that he got his first exposure to the industry and it did not take him long to begin campaigning for worker rights.

The rapidity with which Pritchett joined the labor movement was no doubt caused by the deplorable condition of the camps where he worked. The forest industry consisted of two different types of occupations: mill workers and loggers. Though quite different, both involved miserable and dangerous conditions. Aside from the strenuous physical labor – in 1919, not much mechanized machinery had found its way into the industry – the workers in logging camps had to deal with nearly unbearable conditions at the bunkhouses where they stayed. One logger, an old-timer from Sweden named Charlie Hemstrom, remembered “going into the pig pen to get some straw to sleep on. The pigs had some nice straw … we washed in a hole outside.”6 After a long day’s work, the men piled into the bunkhouses, their wet clothes drying, filling the air with a suffocating dampness. The boarding conditions were exacerbated by long hours and very low pay. In addition, the lumbermen were in constant danger of physical harm while working in the lumber industry. As historians Jerry Lembcke and William Tattem write, “Safety regulations and inspections were either non-existent or ineffectual, and every week loggers fell beside trees” or were injured or killed in the mills.7 The conditions served as a major source of discontent for the men. The camps in which the loggers toiled were isolated, and it took a special type of man to handle the work. In a situation where there was little opportunity to communicate with anyone outside of the camp for extended periods of time, a strong bond was formed, a fraternity of men who understood each other’s situations. This brotherhood, in both the camps and the mills, contributed to the development of a strong labor movement that fought to improve the lives of woodworkers. And it was this labor movement that Harold Pritchett joined in 1924, signing up for the Vancouver local of the AFL Shingle Weavers Union and setting the course for the rest of his life. 8

The Northwest quickly became known as a radical stronghold in the early twentieth century. With its extensive mining and logging industries, the Northwest and British Columbia were fertile grounds for labor unrest and radical ideologies such as Marxism. Many of the workers were Scandinavian immigrants who brought with them a penchant for radicalism. The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW, also commonly known as the Wobblies) was especially active in the Northwest and recruited heavily in the lumber industry. Many of the Scandinavian Wobblies from the Northwest and Canada would participate later on as leaders of the National Lumber Workers Union, a Communist-led organization.9 This active history provided a strong radical legacy for Pritchett to join.

Once Pritchett joined the labor movement, he rose quickly in its ranks. After his initial work in the saw mills, Pritchett went on to be employed with the shingle weavers, first as a shingle packer, then as a shingle sawyer.10 It did not take long for him to hold a position of leadership. A mere three years after joining the labor fight, Pritchett, now employed at the Fraser Mills, became an official in the Shingle Weavers’ Union in 1927.[11

The Shingle Weavers were part of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), which was the largest organized labor association and usually the only one that employers would recognize. The only other acceptable union option for woodworkers was the government-sponsored Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen (LLLL). The 4-L was the federal response to labor radicalism during World War I and was not well respected by labor’s militant leaders.12 The AFL was a craft based federation, which meant it was opposed to the idea of an all-inclusive industrial union that organized “unskilled” workers of a particular industry alongside skilled workers, let alone the notion of “one big union” advocated by the IWW. The AFL’s selective membership effectively ostracized most of the woodworkers. The woodworkers were an eclectic group, comprised of lumber and sawmill workers, plywood and veneer workers, pile drivers, coopers, shingle weavers, furniture workers, and boommen and rafters,13 and most found themselves unrepresented in the AFL. The elitist, old-style attitude of the AFL would prove to be an issue later on.

Pritchett was quickly becoming a leading figure in the Northwest’s union community. In 1931, he rose to prominence when he chaired the Fraser Mills Strike Committee. By 1933, at age twenty-nine, Pritchett was president of a Shingle Weavers local. In a meteoric rise to power, Pritchett had asserted himself as a dominant influence in the labor movement, a powerful organizer, and a charismatic leader. However, in what was perhaps the first move in a major battle that would rage for more than ten years, the American Federation of Labor expelled the Pritchett-led Shingle Weavers local and renounced their charter. The reason? “On the grounds that the Union was in the hands of Communists.”14

Communism and anti-Communism in America

From the onset, communism never sat well with the political and business leaders of the United States. For the ideals of the movement to come to fruition, a complete restructuring of the U.S. government and economy was necessary. That meant revolution, whether sudden or evolutionary. That, in turn, meant the imminent loss of power of the privileged wealthy. And the privileged had vowed to fight.

The foundation for the fight was laid in 1903, when Congress passed an immigration law allowing for the deportation of those who advocated anarchism (which was often erroneously conflated with communism and socialism).15 The extent to which the United States was going to resist communists was demonstrated early in what was later dubbed the “First Red Scare” from 1917 to approximately 1921. The First Red Scare was a reaction to the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and the upheaval of World War I. The fear manifested itself in an unprecedented use of federal power to crush what were deemed subversive activities.

From the beginning, the federal government showed a penchant for attacking labor. The IWW was the first major victim and became the template for future labor suppression. Congress expanded the immigration law in 1918 so that alien members of a group which advocated revolutionary views could be deported, even if they, themselves, didn’t personally support the overthrow of the government.16 Other legislation included the Espionage Act of 1917 and the Sedition Act of 1918, which further limited free speech.17State and local governments in the Northwest passed criminal syndicalism laws that were used often to persecute radicals and undermine the labor movement.18 These laws, all of which restricted civil liberties, set a dangerous precedent and were a dire warning to labor.

On the fateful day of November 7, 1919, led by future FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, the Justice Department rounded up 1,100 workers, many with loose or nonexistent ties to the Communist Party, in what became known as the “Palmer Raids.” 249 of these, most without a proper hearing, were deported to Russia.19 The powers of the United States were obviously highly allergic to the Communist Party and would go to extensive ends to prevent a worker coup. Similar situations existed north of the border in Canada. Though, on the whole, less aggressive in their persecution of radicals, British Columbia was by no means a safe haven for leftists as a “red scare” swept Canada as well. This aggressive and ongoing protection of the status quo in the U.S. would be a major factor in Harold Pritchett and the IWA’s history.

From Early Union Leadership to the Federation of Woodworkers

From the onset of his work in the sawmills, Harold Pritchett immersed himself in Marxist writings and doctrine. The lumber camps proved fertile ground for the ripening of communist ideals. Through “his discussions with his workmates and regular reading of Marxist literature, [Pritchett] had developed into a politically astute union activist.”20 Jerry Lembcke and William Tattam, in their book One Union in Wood, assert that Pritchett, after first joining the socialist Independent Labour Party, was recruited to the Communist Party and became an active member.21

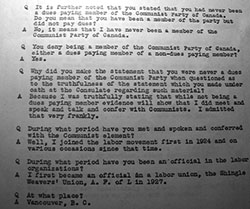

Because labor organizers were well aware of the negative connotation affiliation with the Communist Party carried, it is not easy to find conclusive evidence of membership. In fact, throughout all sources, such as public correspondence, hearing proceedings, and newspapers (even publications with known Communist connections), Pritchett denied Communist Party membership. In the Timberworker, the official organ of the IWA with known Communist editors and affiliations, Communist Party membership was repeatedly denied by leaders of the union and any accusations were dismissed as viscous “red-baiting.” In official hearing proceedings on Harold Pritchett by the U.S. Department of Labor, Pritchett was repeatedly asked, “Are you a member of the Communist Party of Canada?” And Pritchett always responded, “No.”22

However, Pritchett readily admitted to having strong ties to the Communist Party. At a particular hearing in Vancouver, B.C., Pritchett expounded on his Party connections while under oath. Pritchett stated that he began conferring with the Communists when he joined the labor movement in 1924. While he was working in Port Moody (where he had grown up and continued to live as an adult), he attended several meetings of the Communist Party. However, Pritchett specified that the meetings were “open door,” meaning that one did not have to be a member to attend. Participating did not automatically insinuate membership. Pritchett admitted to attending twenty or so meetings.23

In a strange coincidence, the Communist Party of Canada owned property directly next door to Harold Pritchett in Port Moody. That property was used not only for meetings, but also for children’s summer camps put on in cooperation with the Communist Party and the Young Communists League, in which Pritchett participated heavily as an organizer. He helped with the sports, swimming, and most other activities. Pritchett, the father of five small boys at the time (ages 3 to 12), also had his children attend the camp with his wife, Hazel. It was a family affair: the children attended instructional classes and put on plays acting out union strikes with employers. The stated purpose of the camp was to provide children who were on relief a vacation (Pritchett was on relief from 1932-34),24 but the political implications seem obvious.

Therefore, regardless of the lack of absolute evidence, we might assume that Harold Pritchett was indeed a member of the Communist Party. Everyone who was associated with him knew it, and his policies and actions as a union organizer indicate a commitment to Communist objectives during the Depression: advocating working-class solidarity, a united labor front, civil rights, and social reforms.

The Depression years were marked by increased labor action, which resulted in heightened awareness of workers to the class struggle. However the movement was fragmented and unorganized. According to Lembcke and Tattam, “The deteriorating working conditions, high unemployment and low wages that accompanied the onslaught of the 1930s spawned walkouts and sporadic, quick strikes led by short-lived camp or mill committees.”25 The chaotic situation was a prime environment for communist rhetoric and Harold Pritchett, along with his longshoreman colleague Harry Bridges, quickly gained the reputation of being an effective and powerful organizer. Union membership jumped to unprecedented levels as workers responded to the call, “Organize! Organize! Organize!” which was often distributed in literature propaganda.26 Communist organizations, such as the Trade Union Unity League (TUUL) and the National Lumber Worker Union (NLWU) led the way in the early 1930s.27 They were met with opposition at every turn, though, from the outspoken anti-Communist AFL, which tried to limit Communist influence with blacklists and cooperation with the employers. The Communists, realizing that collaborating with the AFL was not an option, followed the policy of “dual unionism;” instead of trying to change the AFL, they organized along side it as a rival union.28 Their work was extensive, especially in British Columbia, Canada, where groups of grassroots organizers would sneak from camp to camp and kindle discontent with the employers and working conditions.

However, despite the increase in union membership, workers saw little to no improvement in their situation. During the labor organizing activity amongst the lumber workers, the fragmented movement began to coalesce, but still lacked a central organizing body. After years of limited gains with employers, the Communists ended the policy of “dual unions” and instead opted for a strategy of “boring from within,” or joining AFL locals and attempting to gain a leftist foothold within the giant federation. The AFL, grasping this opportunity to vastly increase their membership, stepped in and organized the Northwest into 90 FLUs.29 An FLU, or federal union, was essentially the halfway point between being recognized as a local and being issued a charter for AFL membership. They came under the jurisdiction of Bill Hutcheson, the president of the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners (UBCJ). Almost overnight, the AFL had added nearly 70,000 dues paying members to its ranks.30Hutcheson sent Abe Muir, an executive board member of the UBCJ, to spearhead the battle for positive change in the lumber industry. Now, with a loose confederation known as the Sawmill and Timber Workers Union, the timber workers went on strike in 1935 with Abe Muir leading the way.31

From the beginning, the lumber workers’ relationship with the AFL was strained. This was demonstrated in the Great Strike of 1935. It was clear from the onset that Muir and the AFL would be setting the terms with little attention paid to the rank-and-file. Muir negotiated closely with the employers but could not gain the support of the locals. In Muir’s first attempt at a settlement, the timber workers rejected his “compromise” with the employers by a vote of 8 to 1, largely as a result of Communist opposition.32 In the end, after months of striking, the workers were urged back to work by the influence of the Secretary of Labor on the terms of Muir and the employers.

Little is documented of Harold Pritchett’s activities during this time. As stated above, he was president of the Shingle Weavers until 1933. He did not hold office continuously,33 and it can be assumed he spent his down time out in the field organizing the rank-and-file. He was making his presence known, though, as he would again step into union leadership in 1935. Pritchett’s actions and that of the Communists were having an impact on the AFL. The rank-and-file were dissatisfied with the outcome of the 1935 strike and, spurred on by the Communist organizers, felt that Muir and Hutcheson had not shown the lumber workers respect. The craft-based UBCJ gained the reputation in the industrial Northwest woods of being high-handed, haughty, and a little too big for timber worker britches. The stage was being set for a showdown between the respected Communist organizers and the powerful AFL.

The UBCJ made several mistakes while dealing with the woodworkers. First of all, Abe Muir failed to win any significant concessions during the great strike of 1935. Also, they blatantly exhibited their elitism by only allowing the woodworkers fraternal status, which didn’t include full voting rights, despite the fact that the UBCJ collected dues.34 This was seen as an undeserved insult to the integrity of the woodworkers. When lumber locals’ delegates attended a 1936 UBCJ convention in Florida, having traveled across the entire continent, they were designated as “non-beneficial” and were forced to observe the proceedings without a vote.35 The familiar cry of, “No taxation without representation,” echoed throughout the Northwest woods. The arrogant AFL just was not compatible with the rough timber workers. The timber workers felt discounted because they were designated “unskilled” workers and the AFL put little effort and money into organizing the woods. To make matters worse for the UBCJ, Harold Pritchett again stepped into power (after having been relieved in 1933), taking control of the District Council in British Columbia.36 The “boring from within” tactic had worked. The central UBCJ leadership had earned a reputation for doing nothing while the Communists within the organization, Harold Pritchett safely at the helm, solidly held the respect of their fellow workers.

With the rank-and-file thoroughly disappointed in the AFL and, more specifically, the UBCJ, a secret convention was called on September 18, 1936. The woodworkers of the Northwest gathered in Portland and officially banded together as the Federation of Woodworkers, asserting their power in the face of Abe Muir, Hutcheson, and the UBCJ. Harold Pritchett, spring-boarding to power from his position as president of the UBCJ in BC, not only chaired the convention, but was also elected the Federation’s first president. This was a result of the Communists being seen as the premier opposition to AFL elitism. He did not have a clear mandate for power nor the complete support of all the timber workers,37 but the feelings of discontent and desire for change presented the unique opportunity for Pritchett to grab leadership. The woodsmen of the Northwest were now well on their way to building their own identity. As Pritchett wrote, “70,000 industrial woodworkers vulnerable to joint attacks by the employers and top leadership of the AFL,” now had a voice of their own.38 This voice, however, was weak and foundationless. The new Federation of Woodworkers was not chartered by the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners and was officially unaffiliated with any of the major union organizations of the time. The failure of a vote that would have withheld per capita tax from the UBCJ showed that the rank and file still desired contact with the Carpenters.39 But Hutcheson and Muir were not making any attempt to mend the relationship and hostilities loomed.

The CIO: A Brief History

The Great Depression was a time of unprecedented radicalism in labor. Arguably surpassing even the days of the Wobblies (IWW), the early 1930s provided fertile ground for change. The dreadful economic situation left workers, especially those in the industrial sector, desperately seeking a better lot. For many workers, more “civil” or traditional means had failed, and now radicalism was a legitimate option. Change was also brewing in Washington, D.C. The AFL had been at the forefront of union organization since the onset of the twentieth century. However, it focused only on craft-based unions, leaving out the broad market of “unskilled,” industrial workers. As the Depression deepened, so did the idea of a union to represent the ostracized industrial employees. The idea materialized at the hands of radical labor activist John. L. Lewis.

John L. Lewis was the vice-president of the AFL and leader of the powerful United Mine Workers of America. He had become increasingly disillusioned with the AFL and on November 9, 1935, Lewis and eight other union presidents formed the Committee for Industrial Organization, or the CIO.40 As one can gather from the title, the purpose of the CIO was to organize industrial workers. Initially, in a released statement, the CIO promised to cooperate with the AFL, but quickly it became obvious that Lewis had other ideas. It seemed that John L. Lewis wasn’t committed to just industrial workers. He had also created the CIO because it guaranteed him a position as president. Lewis was feuding with the AFL leadership at the time, and many felt that the CIO was just a manifestation of his thirst for power.41

Regardless of Lewis’s intentions, the CIO quickly gained legitimacy and became a thorn in the AFL’s side. There was now a competitor to the AFL’s monopoly on union dues. The CIO tenaciously set out on its mission to organize the unorganized, gathering up unions as fast as it could. Initially, the CIO paid little mind to the IWA because of their organized status, but that relationship would soon blossom.

Let’s Go CIO!

After its birth, the Federation of Woodworkers had voted to stay with the United Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners. This was a temporary arrangement, though, as both harbored irreconcilable differences. Harold Pritchett saw the UBCJ as essentially in collusion with the employers and big business. They were not to be trusted nor collaborated with. Additionally, the AFL’s discrimination against the “unskilled” lumber workers and their under-representation within the UBCJ could not be ignored.

In the Timberworker, the official newspaper of the Federation of Woodworkers, Pritchett and his leftist staff waged a propaganda campaign almost from the very inception of the Federation, printing article after article in favor of officially leaving the AFL for the CIO. The Congress of Industrial Organizations was an industrial union organization, versus the craft based AFL, and, at least in 1937, was relatively friendly to Communists. This was mostly because John L. Lewis, the president of the CIO, recognized the skill of Communist organizers and sought to exploit it to build his federation.42 In a July 2, 1937 Timberworker editorial, Pritchett accused Muir and UBCJ president William Hutcheson of “being wined and dined extensively by the lumber barons.”43 He also accused the AFL of wrongly suspending lumber union charters (referring to an August 4, 1936 incident) and of still not allowing voter representation despite the payment of dues. To Pritchett, being under the anti-communist, elitist AFL went against every one of his radical tendencies, and he passionately ended the editorial with a plea for his fellow workers to renounce the AFL.

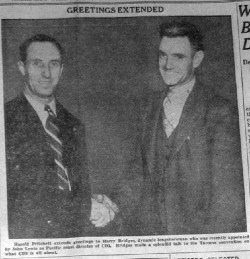

The campaign worked and as reported in the July 23, 1937 issue of the Timberworker, the Federation of Woodworkers voted to affiliate with the CIO by a five to one vote.44 John L. Lewis immediately issued them a charter. The paper featured a front-page photograph of Harold Pritchett grinning like a child at Christmas, clasping the hand of his good friend Harry Bridges. Bridges, recently made regional director of the CIO, had assisted in the Woodworkers’ break from the AFL, and his collaboration with Pritchett caused the anti-left factions to suspect a Communist plot to take over the woodworking industry.45 Following their declaration of independence, the Federation renamed their organization the International Woodworkers of America (IWA) and chose Harold Pritchett as its first president.46

The AFL was not going to let 70,000 dues paying members go quietly from its coffers, and a violent struggle erupted within the labor movement. It would dominate the first years of the IWA and coincide with the rise of Harold Pritchett’s opposition: the anti-left white bloc. The newborn IWA would not have an easy childhood.

IWA: The Early Years

The first chapter in IWA history was composed of a complex power struggle. On a nationwide scale, there was an ongoing battle over who would control the reinvigorated labor movement. This conflict trickled down to the local level and incarnated itself at Pritchett’s doorstep in the form of Al Hartung, the hardline leader of the Columbia River District Council (CRDC) within the IWA.

Al Hartung wanted to be president. He had detested Pritchett’s leadership since the beginning. At the 1937 convention, which brought the IWA to fruition, Hartung contested Pritchett’s presidency until it was validated by a vote of the rank-and-file.47 He would play the antagonist in the next chapter of IWA history, but after the convention, Pritchett first had to deal with the AFL counter-attack.

The AFL launched a boycott of all IWA produced goods and refused to recognize IWA jurisdiction over the newly converted locals. The boycott was possible because the AFL closely collaborated with the Teamsters, the truck drivers who transported the products, and the builders who would use the IWA timber. Jurisdictional warfare erupted when AFL picketers attempted to block production in the IWA mills. Tensions were high and violence was nearly a daily occurrence, especially in Portland where seven mills were shut down for over half a year.48 Both political and physical battles were fought, but in the end, Harold Pritchett and the International Woodworkers rose mostly victorious, although the IWA never gained control of all the Northwest locals. The IWA victory was due in no small amount to Pritchett’s collaboration with Harry Bridges, other leftist union leaders, and the state government.49 In a controversial move, Pritchett had called off pickets which had been placed along the docks of the longshoremen at the behest of Bridges, angering Al Hartung and the CRDC. This instance would come back to haunt Pritchett as many would later use it as evidence of Communist Party control of labor.

Similar to the previous battle with the AFL, Pritchett waged a strong propaganda campaign in the Timberworker. Many articles condemned Hutcheson and the AFL leadership. Most of Pritchett and the IWA’s grievances stemmed from the 1935 strike and the actions of the UBCJ leadership involved (namely Muir and Hutcheson). However, new offences had been committed in the open hostilities that erupted in the aftermath of the IWA’s move to the CIO. IWA members had been physically attacked with baseball bats in an AFL attempt to halt production.50 It was also widely believed that Hutcheson had been collaborating with city officials and employers, especially given the police’s lack of intervention in the violence.51 Harold Pritchett wrote in an editorial, “Unity and brotherhood mean nothing to Hutcheson in his eagerness to serve the employers. He will knife anyone, or any union, in the back – and demand that they like it. Let us have no more repetitions of Hutcheson’s vicious sell-outs.”52 The IWA was turning into an energetic force behind Pritchett’s radical and militant leadership.

The IWA saw substantial growth under the leadership of Harold Pritchett. Starting out in the Northwest woods, the IWA expanded deep into California, the Midwest, and even down into the South.53 The organization waged many successful strikes against the industry, asserting itself as a powerful collective bargaining agent. According to a report by Pritchett in 1939, membership totaled roughly 100,000 members, though this number has been hotly debated.54 In the Timberworker, Pritchett championed the policy of “organize the unorganized,” especially leading up to the 3rd Annual Convention, and he had made this goal a reality. The IWA was also quite powerful in Canada. Pritchett’s home, the British Columbia District, was one of the largest districts in the IWA. The hierarchy in the IWA consisted of the International offices at the top (Pritchett and his administration); the membership was then split into district councils (such as the CRDC), locals, and sub-locals. A local’s strength depended on its surroundings. In cities such as Portland, the local was strong, encompassing a large number of mills, but in smaller towns, locals might only represent a mill or two.55 The power structure of the IWA lent itself to factionalism and the resulting power struggles would shape its early history.

Pritchett used the Timberworker as his voice to the IWA rank-and-file, writing a near-weekly article, titled “The President’s Column,” to expound upon not only union issues but national and world concerns as well. During his time as president, he kept the Timberworker closely affiliated with communist ideas. Pritchett wrote continually in support of the New Deal and its social reforms, clearly stating his views on how the IWA rank-and-file should vote. For instance, one editorial was unabashedly titled: “‘No’ On Anti-Labor Measures, ‘Yes’ On New Deal Candidates, Is the Rule For Voting Nov. 8.”56 In the lead-up to World War II, Pritchett published many articles blasting fascism, at least up until the Nazi-Soviet Non Aggression Pact in August of 1939, after which the regularity of such opinions dropped dramatically in line with the general policy of the Communist Party. During the Spanish Civil War, the Timberworker aligned itself with the “reds” fighting Franco and glorified the revolutionaries participating in the war. In addition, Pritchett often wrote in favor of civil rights and liberties and the need for a united labor front.57 He wrote motivational pieces championing the worth and power of the working class which usually were quite spiteful of the elite. As Pritchett wrote on September of 1939, “Slums only exist where workers live and can never be found where employers live … the answer is to build a strong international union.”58 Much space was also used to praise the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, commonly known as the Wagner Act, which guaranteed to workers “the right to self-organization, to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choosing, and to engage in concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid and protection.”59 As the war neared, in 1940 especially, the Timberworker filled up with anti-war articles (again, most likely as a result of the Hitler-Stalin pact). At one point, Pritchett blamed the war for the suffering of thousands of fellow workers in Europe.60 All these opinions fell close in line with Communist Party policies of the time.

In “The President’s Column” Pritchett revealed himself as not only an opinionated, charismatic labor leader, but as a powerful writer as well. He wrote with a complexity that belies the fact that he stopped schooling at age fifteen, and it is obvious he was well read. Pritchett deftly conveyed his belief “that union action should be premised on the understanding that the interests of employers and employees were not the same,” and that only militant labor action could procure the desired results.61 This militant platform came out in Pritchett’s writing style, which was forceful and emotional. He truly conveyed his passion for the plight of labor. “The President’s Column” always included a call to action and an affirmation of the movement’s value and strength. As Pritchett wrote in his December 3, 1938 column, “…our people have not faltered in their conviction that they have rights which must not be destroyed.” In a way, the column served as a weekly pep talk to the rank-and-file and an occasion to indoctrinate them with Pritchett’s own political beliefs.

This fact, and many others, kept Al Hartung and what was now called the Opposition Bloc (or White Bloc) on the edge of their seats and clamoring for conservative reform of the IWA. Their faction hailed from the Columbia River District where the locals had never been entirely behind Pritchett’s leadership and had even resisted joining the CIO. They participated in many attacks on Pritchett, usually in the form of red-baiting, which was the most destructive and effective political assault of the time.

Harold Pritchett, like many union leaders during the period, came under the intense scrutiny of the U.S. Federal Government. Pritchett experienced more attention than most because of his status as an immigrant, being a citizen of Canada. Since his election as president of the IWA, Pritchett had entered the United States many times on visitor’s permits, but had never been allowed a visa or a chance to gain citizenship (which he desired for his family).62 The official reason was, of course, his affiliations with the Communist Party.

Both Pritchett and Harry Bridges were “tried” by the House Committee on Un-American Activities, known by unionists as the Dies Committee after its chairman, Texas congressman Martin Dies.63For Pritchett, the hearing took place in the summer of 1938. This issue was covered extensively in the Timberworker, which wasted no time in condemning the Dies Committee as the strong arm of Big Business, calling it a direct attack on the IWA. In his presidential address at the 1939 IWA convention, Pritchett revealed some of the charges brought against him, many by colleagues in the labor movement. Mr. Harper L. Knowles, a witness used against both Bridges and Pritchett and a “self-appointed California expert on radicalism,”64 testified in 1938,

“Harold J. Pritchett, president of the International Woodworkers Federation, and a citizen of British Columbia, was reported in this country to be an active member in high standing of the Communist Party. He has been granted repeated visas by the Department of Labor to visit the United States in the furtherance of his program of disrupting the lumber industry in this country. Repeated protests to the Department of Labor have proved unavailing, as Pritchett is given carte blanche to visit this country whenever he desires to do so and to remain as long as he wishes…[allowed by] the Department of Labor with its usual flagrant violation of the law…”65

It was widely known that President Roosevelt’s Secretary of Labor continually overrode attempts to bar Pritchett from entry.66 Pritchett went on to charge the Dies Committee of threatening the very foundation of democracy and civil liberties.

While many opponents of Pritchett called for his deportation to Canada, he never had an official deportation hearing. Harry Bridges, however, had quite another story. Bridges was constantly hassled by the government and the legislature even gave Bridges his very own law when Congress passed the Allen Bill in 1940, which authorized and directed the Secretary of Labor to deport Bridges.67 In 1939, the entire labor movement was faced with the possibility of losing one of its most dedicated organizers when Bridges, faced with deportation, went on trial for subversive (communist) activities. Originally from Australia, Bridges had never attained citizenship and remained officially an alien. Being a labor radical, this fact put him in great jeopardy. The 1939 trial lasted nine-and-a-half weeks and produced a 7,724 page transcript.68 However, despite the extensive effort by the government, Bridges escaped unscathed. This was for a number of reasons but mainly due to the fact that, by a stroke of luck, the chair of the hearing was Dean Landis of Harvard University. Landis doubted (rightly) the legitimacy of the government’s witnesses and appeared to have an admiration for the accused, engaging in friendly, “long philosophical discussions” with Bridges while he was on the stand.69In the end, six years, three more trials, a law, and endless government harassment later, Harry Bridges was acquitted and allowed citizenship by a Supreme Court ruling.70 Bridges’ story is an example of the struggle radical labor leaders had to endure. Pritchett and Bridges encountered similar experiences, the major difference being that Pritchett ultimately was not victorious.

The Dies Committee proceedings and the trial of Harry Bridges were a clear indicator of the danger Pritchett was in as a resident alien. His position as president of the IWA was in the hands of the State Department. He knew that if he could not be in the United States, he could not lead the International Woodworkers of America. His dire situation gave Al Hartung and his Opposition Bloc the perfect route to remove Pritchett from the presidency.

In the 1938 convention, Hartung again caused a ruckus, threatening to withdraw the CRDC from the IWA, but he did not yet have enough support amongst the rank-and-file and had to back down.71 Conditions were turning towards chaos, though. In the woods of the Northwest, violence was erupting. In the quiet town of Aberdeen, Washington, conditions came to a head. The wife of a prominent Communist union leader, Dick Law, was brutally beaten to death. It was clear that Laura Law had been killed by the associates of the Opposition Bloc. The Timberworker spent a lot of print placing the blame.72 It was becoming obvious that Hartung and the Opposition Bloc would stop at nothing to see their means furthered.

In the midst of the gathering storm, Harold Pritchett stood fast. In an impassioned address in the Timberworker, Pritchett classified those that were tearing the union apart as, “liars, finks, stool pigeons and shysters.” He went on to write, “Labor’s great strength has always been in its solidarity. The solidarity of one human being with another, no matter what racial, occupational, political or religious differences are involved, has been the glory of this democracy and the fountainhead of labor’s power.”73 But despite his desire for unity, Harold Pritchett was going to have to fight for the union he had devoted his life to.

The 1939 Convention and Elections: The Rise in White Bloc Power

Hostilities finally exploded in full force the fall of 1939 at the Third Annual Convention of the IWA. Al Hartung and Don Helmick, also from the CRDC, promised to oust the Pritchett-led Communist administration from the International Union. The showdown would occur in Klamath Falls, Oregon, a beautiful small town near the California border.

The press coverage for the event was highly charged and accusations flew from each side. Pritchett tried to calm the situation by attempting to prevent red-baiting, warning that worrying about communism was going to waste valuable time and scare away potential members. But he also showed that he wasn’t going to back down from a fight. “There’s Communists in that organization, and they’re staying there. And it’s a pretty good organization, a darn good organization … God help the person that starts kicking out Communists, or anybody else. Because the Organization will take care of him.”74

Hartung and the Opposition Bloc wasted no time in attacking. They proposed an amendment to the IWA’s constitution that would bar Communists from holding office. It failed to pass, and the Opposition Bloc blamed the presence of Harry Bridges and his collaboration with Pritchett.75 In a campaign poster, (Al Hartung was again running for President of the IWA), Hartung accused Pritchett and his administration of using the IWA as a Communist front organization.76 The Portland Journal, closely affiliated with the Republican Party, took up the cause of the Opposition Bloc:

“…it is inspiring to witness the anti-communist wave rising in labor. Communists are not Americans at heart, and cannot be. Nazis and Fascists are not Americans in heart, and cannot be. Silver Shirts, Brown Shirts and Black Shirts are not Americans in heart, and cannot be. Why? Because democracy, in the American concept, means equality of opportunity, equal standing before the law, freedom of speech, press and belief—-the bill of rights of the individual.”77

Despite the valiant effort of the Opposition bloc, its anti-Pritchett resolutions failed and Al Hartung went on to lose the election to Pritchett by a count of 7,100 votes to 9,332.78 But Hartung wasn’t going to just wait for another year this time. He protested the results with the national offices of the CIO. John L. Lewis responded with a confusing and contradictory statement. In one sentence, he wrote, “If there are any budding young communists who think they can make a life work of taking over the [CIO] for the Communist party, they had better forget it. There is no future for them.” Then, in the next, “There will be no witch hunts or red hunts and any union has the right to elect or select anyone it chooses to lead it.”79 Thus, it seemed the national office had defended Pritchett, but the reality would turn out different. Despite Pritchett’s immense success as President (the IWA had added $12,000 in dues revenue in 1939 alone80), the CIO began to show signs it was looking for a different leader for the woodworkers. Reports surfaced that national CIO representatives were getting involved in the fight. Those reports proved to be true as the tide turned even further against Harold Pritchett in 1940.

The Deportation of Harold Pritchett

1940 proved to be a decisive year for the International Woodworkers of America. It started off with high drama following Harold Pritchett’s defeat of Al Hartung in the rank-and-file referendum vote for president of the IWA. The Opposition Bloc immediately accused Pritchett of cheating in the election, even though Worth Lowery, from the CRDC, was elected to a newly created vice president position. However, the need for Hartung to pursue a different course to block Pritchett’s presidency became necessary when William Dalrymple, regional director of the CIO, declared the election honest and fair.81 This was seconded by Michael Widman of the National CIO office. In protest, Hartung decided to starve the central office of the IWA by ordering the per-capita tax of the CRDC withheld.82 The rank-and-file of the CRDC detested this move, however, and caused a ruckus with multiple editorials in the Timberworker.83Finally, with prompting from CIO headquarters, Hartung removed the order, especially when local papers began to accuse him of taking part in an AFL plot.84 In a meeting of the executive council of the IWA, it seemed that Pritchett still had solid support at least within the council as proposal after proposal from the CRDC (including one requesting Harold Pritchett’s resignation) was shot down by overwhelming votes.85

This job security was not to last. During the rest of 1940, conditions continued to worsen for Pritchett. Knowing that his union was splitting in two, he wrote an emotional plea for unity in the Timberworker. The employers were the root of the problems the union was experiencing, wrote Pritchett, and for labor to win, it must stay completely united.86 In an attempt to foster unity, Pritchett focused his President’s Column on union issues, rather than the political battle that was ferociously being waged for control of the IWA. Perhaps this was to remind the rank-and-file that their leadership did indeed work for them, when so many of the major articles in the _Timberworker_were devoted to internal and international issues.

The rank-and-file made their voice heard as well. The Timberworker had a section titled “Rank-and-File Opinion” where anyone could write in and have their thoughts published. Many union members wrote the Timberworker during the upheaval and expressed support for Pritchett and his policies. Judging form the articles in the Timberworker, a majority of the rank-and-file sided with Pritchett. Many historians have argued that Pritchett’s power was illegitimate, having no clear mandate from the rank-and-file, but in recent years new analysis has shown that on the whole, Pritchett retained widespread support.87

The arrival of Adolph Germer changed things. He was sent by the CIO International Office to help the organizing effort.88 Germer’s arrival was a direct result of a plea for help from Pritchett and the leftist leadership of the IWA amidst the chaos of the AFL fight and the CRDC revolt.89 This was a fateful move. Instead of being a savior, Germer became the wedge that drove Harold Pritchett out of the IWA and the United States. Germer and Dalrymple, who were supposed to be impartial, became quite friendly with the CRDC and did not attempt to hide their political opinions.90 Strongly anti-communist, Germer had come to finish off Pritchett and his Communist-backed administration. The CIO International Office had been meddling in the IWA’s affairs for quite some time. Reports had surfaced in February of 1940 that CIO officers were secretly meeting with CRDC members, plotting the ouster of Pritchett.91 Sworn affidavits of those involved indicated that the CIO was knowingly conducting subversive activities with Pritchett’s opposition. There was little Pritchett could do about this, and John L. Lewis was playing innocent.92 In an article that was grudgingly printed in the Timberworker, Dalrymple wrote, in an indirect attack on Pritchett, “The CIO is not a Communist Party, It is a labor organization, an American labor organization.”93 At least that was what Dalrymple, Germer, and the Opposition Bloc had set out to make a reality. Pritchett, realizing his folly, requested that Lewis remove Germer.94 But it was already too late; Lewis had no intention of calling Germer home.

On July 7, 1940, the Timberworker reported that Pritchett had applied for a permanent visa. Knowing that the hearing was likely to be slanderous, Pritchett requested an open hearing so that the imminent red-baiting could at least be public knowledge. Pritchett desired that “charges and accusations, emanating from anti-labor groups be discredited and the continuous questioning of [his] integrity and undermining of [his] character be stopped for all time.”95 This was to be his last opportunity for entrance to the United States before the 1940 convention, as his visitor’s permit had expired and would not be renewed. His chances were not good, though; his previous attempts for a visa had been rejected because of his Communist affiliations.96

The hearing went as predicted, which was not in Pritchett’s favor. During the hearing, numerous witnesses were called, labeling Pritchett as a Communist. The hearing, led by Paul E. Josselyn (the U.S. Consul in Vancouver), referred to a funeral, which occurred in October of 1935.97 Pritchett had been quizzed on this occurrence in many previous hearings and it seemed to be one of the main pieces of evidence for the US State Department.98 The incident was a funeral service conducted by the Communist Party in Surry, British Columbia for James Roebuck. The obituary that was printed the next day stated that the service was Communist led and that Harold Pritchett had spoken. In the eyes of the State Department, this directly implicated Pritchett as a Communist. The obituary also stated that the participants wore red armbands and waved red flags, which Pritchett denied. As Pritchett told the story, Mr. Roebuck was a good friend, a member of Pritchett’s union, and had been an active participant in the Canadian labor movement with the IWW. When Mr. Roebuck became ill, because he was on relief he did not receive proper medical care and was condemned to the “X ward,” a basement ward reserved for relief patients. Roebuck died in Pritchett’s arms, weighing only eighty pounds. At the funeral, rightfully indignant about the care Roebuck had received, Pritchett stated “that [the] working people would look forward to the day when such untimely deaths were not necessary.”99 After the body was lowered into the ground, those gathered sang the Red International. Now, six years later, Pritchett and his family were being denied the privilege to live in the United States based on this obituary.

The official reasons for denial were that Pritchett failed to prove non-immigrant status (because he had lived in the U.S. almost continually on visitor’s permits since 1936 as he conducted union business) and that he would compromise public safety (because of subversive activities).100 Communism may have been the reason for this “deportation” on the surface, but as the Timberworker editorialized after the news, the IWA was in the midst of a significant drive to organize the Southern timber industry and anti-labor factions desired to prevent the expansion of the powerful leftist labor movement.101

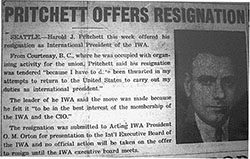

Stuck in Vancouver, BC, Pritchett could not attend the Fourth Annual Convention of the IWA. After legal alternatives failed, it was clear that Harold Pritchett was not going to be allowed legally into the United States for quite some time and that he would be unable to fulfill his duties as president of the International Woodworkers of America.102 And so, with great frustration, Pritchett tendered his resignation to the Executive Board, reported first in the November 30, 1940 issue of the Timberworker, then officially in the December 7, 1940 edition. Vice President O.M. Orton stepped up to fill the position until the elections the following year. In his official letter of resignation, Harold Pritchett wrote,

“It is my only hope and desire that our International Union advance, progress and protect the interests of our membership against reaction, from whatever source. I am cognizant of the powerful reactionary interests, representative of Big Business, who are ruthless in their determination to hinder and retard the growth and effectiveness of our organization, resorting to every foul and despicable means in their attempts to destroy us, and it is with alarm and deep concern I view the unfortunate and misguided disruption within our Union which, I am sorry to say, is being given active comfort and support by officials of the CIO holding offices of directorships; namely, Masers, Francis, _Dalrymple and Germer—_the later appointed to this high position by President John L. Lewis and charged with the responsibility of directing the immediate organizational drive and promoting harmony within our International.”103[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_edn103)

Conclusion: Victory for the White Warriors

Despite the rocky path his three years as president of the IWA had taken, Pritchett’s term can be considered a success. Membership grew markedly during his tenure; the IWA waged several successful strikes and established a powerful collective bargaining presence; Pritchett was able to run the IWA in his militant, leftist style. Essentially, at least up until 1940, he was realizing his vision of a radical union that would truly represent its membership.104

In Canada, Pritchett continued his work for the labor movement wholeheartedly. Outside the reach of American reactionaries, Pritchett’s radical tactics could proceed relatively unmolested. Canada was more conducive to organizing at the time due to its capital intensive industries and a severely exploited workforce.105 He became president of the IWA’s British Columbia District 1 and joined the leadership of the Labor Progressive Party, a communist equivalent which did not advocate violence or force.106Throughout the 1940s, he continued in the vanguard of the struggle of the red-versus-white war that was just reaching full force in the United States. In 1948, Pritchett helped lead a leftist break from the IWA with the formation the Woodworkers Industrial Union of Canada (WIUC). Many parallels between the 1937 IWA split from the AFL and the formation of the WIUC were drawn, and just like the Communist control of the IWA, it was short lived.107 It fell apart in 1951, bringing down Pritchett’s career as a labor organizer with it. Although he tried multiple times to gain re-entry, Harold Pritchett was never again permitted to be a member of the IWA. Returning to his original roots, Pritchett lived out the rest of his working life as a sawyer and shingle weaver.108 Harold Pritchett died in 1982.

In the IWA, the coercive tactics of Germer and Hartung proved successful in the end as the White Bloc assumed control and reformed the union in Pritchett’s absence. As the 1940’s progressed, it became clear that the battle for the IWA had been one of the first in the overall reform of the CIO and the labor movement. According to historians Jerry Lembcke and William Tattam, John L. Lewis, despite his superficial support for Pritchett, had actually backed the Pritchett “deportation” and was behind the CRDC takeover (Hartung was finally elected President of the IWA in 1943).109 Harold Pritchett had been one of the first casualties of the “Second Red Scare” that would continue in the United States deep into the 1950s.

But as one reads through Harold Pritchett’s history, what emerges is not a violent Communist who desired to overthrow the capitalist government. Rather, Pritchett was a man who gave his life’s work to helping working people. For him, the best way was the Left way, but it really wasn’t a political issue for Pritchett, it was a human one. Time and time again, Pritchett stressed unity in the movement and the power of the rank-and-file. For Pritchett, being a woodworker was the harsh reality of the job. This reality transcended politics, but politics was also a reality, and it was a game Pritchett was willing to play.

copyright © Timothy Kilgren 2008

HSTAA 498 Autumn 2007

1 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 1

2 Ibid.

3 “Inventory of Harold Pritchett Papers,” University of British Columbia Special Collections. http://www.library.ubc.ca/spcoll/AZ/PDF/OP/Pritchett_Harold_James.pdf, accessed on Nov 10, 2007.

4 Ibid.

5 Jerry Lembcke and William Tattam, One Union in Wood (British Columbia: Harbour Publishing, 1984), 23.

6 Myrtle Bergren, Tough Timber (Toronto: Progress Books, 1966), 23

7 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 19

8 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 6

9 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 16

10 Ibid, 7

11 Ibid, 6

12 Jonathan Dembo, Unions and Politics in Washington – 1885-1935(New York & London: Garland Publishing, Inc, 1983), 538.

13 “Communism in Washington State History and Memory Project” by Brian Grijalva, http://depts.washington.edu/ labhist/cpproject/grijalva.htm (accessed on Nov 16, 2007); Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 43

14 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 7

15 David Cole, Enemy Aliens: Double Standards and Constitutional Freedoms in the War on Terrorism (New York: The New York Press, 2005), 108.

16 Ibid, 111

17 Ibid. 114

18 “Oregon Criminal Syndicalism Law,” by William Long, http://www.drbilllong.com/LegalHistoryII/ SyndicalismIII.html (accessed on Dec 08, 2007).

19 Cole, Enemy Aliens, 119.

20 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 23.

21 Ibid, 24

22 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 6

23 Ibid, 8

24 Ibid.

25 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 20.

26 Timberworker, Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, passim

27 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 20

28 Ibid.

29 Irving Bernstein, Turbulent Years: A History of the American Worker 1933-1941 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1970), 624.

30 Ibid.

31 Ibid, 625

32 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 27; Bernstein, Turbulent Years, 625.

33 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 7

34 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 43.

35 Bernstein, Turbulent Years, 627. “Non-beneficial” essentially meant they were not seen as legitimate members because of the UBCJ’s craft-based bias.

36 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 43.

37 Bernstein, Turbulent Years, 627.

38 “A History of the IWA – Pritchett letter to National CIO,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder

39 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 44.

40 Bernstein, Turbulent Years, 401.

41 Ibid, 400

42 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 78.

43 “A.F.L. vs. C.I.O,” Timberworker, July 2, 1937.

44 “Woodworkers Go CIO by Five to One Vote in Tacoma,” Timberworker, July 27, 1937.

45 “Press release Oct 27, 1939 from the Union Register,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475. Box #1, History Folder.

46 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 11

47 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 54.

48 Bernstein, Turbulent Years, 629

49 Ibid, p. 57.

50 Bernstein, p. 629.

51 Lembcke & Tattam, p. 56.

52 “Hutcheson’s Treachery,” Timberworker, Jan 7, 1939.

53 Lembcke & Tattam, p. 47 & Timberworker, September 14, 1940.

54 “A History of the IWA – Pritchett letter to National CIO,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder

55 Email, Steve Beda, Dec 02, 2007.

56 “‘No’ On Anti-Labor Measures, ‘Yes’ On New Deal Candidates, Is the Rule For Voting Nov. 8,” Timberworker, Nov 5, 1938.

57 “Dies, Hague Must Go; Civil Rights Must Win; Boss’ Terrorism Must Stop, So Labor Can Rise,” Timberworker, Dec 3, 1938.

58 Timberworker, Sept 9, 1939.

59 “National Labor Relations Act (1935)” author unknown, http://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=true& doc=67 (accessed on Dec 08, 2007).

60 Timberworker, Nov 4, 1939.

61 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 24.

62 “Wants U.S. Entrance To Get Citizenship Asks Public Hearing,” Timberworker, July 27, 1940.

63 “Dies, Hague Must Go; Civil Rights Must Win; Boss’ Terrorism Must Stop, So Labor Can Rise,” Timberworker, Dec 3, 1938.

64 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 61.

65 “President’s Column,” Timberworker, Dec 30, 1939.

66 Ibid; Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 76.

67 Charles P. Larrowe, Harry Bridges: The Rise and Fall of Radical Labor in the United States, (New York, Westport: Lawrence Hill and Co, 1972), 221.

68 Ibid, 215

69 Ibid, 217

70 Ibid, 246

71 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 63

72 Timberworker, Jan 20, 1940.

73 “President’s Column,” Timberworker, Jan 6, 1940.

74 “A History of the IWA – Pritchett letter to National CIO,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder.

75 “Press release to Union Register, Oct 27, 1939,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder.

76 “Campaign Poster Nov 16, 1939,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder.

77 Portland Journal, Oct 21, 1939. Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder

78 “1939 Election Results,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder.

79 “‘There Will Be No Witch-Hunts’ – John L. Lewis,” Timberworker, Dec 2, 1939.

80 “Membership data table,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder.

81 Timberworker, Dec 16, 1939.

82 Timberworker, Jan 13, 1940.

83 Timberworker, Jan 20, 1940.

84 Seattle PI, Jan 8, 1940, Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder. & Lembcke & Tattam, p, 75

85 “Executive Council Minutes, Jan 11-12, 1940.” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder.

86 Timberworker, Jan 27, 1940.

87 See Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood versus Vernon Jenson, Irving Bernstein.

88 Timberworker, July 13, 1940.

89 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 79.

90 “Communists Do Not Speak For CIO, Dalrymple Writes,” Timberworker, August 31, 1940.

91 “Affidavit of Bertel J. McCarty,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, History Folder.

92 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 87

93 “Communists Do Not Speak For CIO, Dalrymple Writes,” Timberworker, August 31, 1940.

94 Bernstein, Turbulent Years, 630.

95 “Wants U.S. Entrance To Get Citizenship; Asks Public Hearing,” Timberworker, July 27, 1940.

96 Ibid.

97 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 77

98 “Untitled Brief history,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder.

99 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 15

100 “Pritchett To Appeal Visa Denial,” Timberworker, August 31, 1940.[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref100)

101 Timberworker, September 14, 1940.[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref101)

102 Many documents in Xerox folder follow legal council on Pritchett’s options,; Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder.[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref102)

103 “Pritchett letter of resignation,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref103)

104 This conclusion is based upon conversations and correspondence with Steve Beda, a graduate student in the UW History Department. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Steve, who has tirelessly counseled me throughout the writing process. In addition, I would like to express my appreciation to Prof. James Gregory, who also has spent much time counseling the progress of this essay.[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref104)

105 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 103.[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref105)

106 “U.S. Dept of Labor Hearing – September 14, 1945,” Harold Pritchett Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Acc # 1475, Box # 1, Xerox Folder, 17[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref106)

107 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, 128.[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref107)

108 Andrew Neufeld & Andrew Parnaby, The IWA in Canada: The Life and Times of an Industrial Union (Vancover: New Star Books, 2000), 300.[](Harold_Pritchett.htm#_ednref108)

109 Lembcke and Tattam, One Union in Wood, chapters 4-6.

--Feb.%205,%201937--p.1.250w.jpeg)

--Feb.%2026,%201937--p.1.250w.jpeg)

--July%2030,%201937--p.5.250w.jpeg)

--July%2030,%201937--p.2.250w.jpeg)

--June%2018,%201938--p.1.250w.jpeg)