A rising tide of anti-immigrant and anti-radical politics swept the United States following World War I, and Seattle area politicians played an important role. It’s well-documented that defeat of the Seattle General Strike of 1919 helped pave the way for anti-labor campaigns across the country. But less well known is the fact that national anti-immigrant politics, particularly anti-Japanese politics of the post-World War I era, had important roots in the Pacific Northwest.

This paper looks at 1920 committee hearings convened by Congressman Albert Johnson on the question of whether to bar Japanese immigration and citizenship claims. Johnson was the co-author of sweeping 1924 legislation that effectively closed America’s borders to non-white immigrants for the next forty years. And his use of hearings in his home district to promote a national version of white supremacy reveals much about the racial politics of post-WWI Seattle and about Seattle’s role in national debates over who could and could not be considered “American.”

Members of the United States Congress arrived in Elliot Bay aboard a steamship on the afternoon of Sunday, July 25, 1920.1 This delegation was part of the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, which was in the midst of an investigation on issues surrounding Japanese peoples on the west coast. Their local investigation commenced in the Seattle courtroom of Judge E.E. Cushman. They broke for lunch at the Rainier Club, took an impromptu tour of Pike Place Market, and retired to Paradise Lodge in the Mount Rainier National Park during recess.2 The committee would stay in the area for over a week, hearing hours of testimony related to the local situation surrounding the Japanese.

A Change in Asian Immigration

Increased industrialization and infrastructure around the turn of the century created a great demand for cheap labor in the United States. Initially Chinese immigrants provided low cost labor. In 1882, the Chinese Exclusion Act stopped the flow of immigrants, and thus the major source of labor on the west coast. Japanese were the primary immigrant group to fill the demand for labor left behind by the Chinese. Initially employed by railroad companies and factories, Japanese immigrants quickly started their own businesses and communities.

The Japanese victory over Russia in 1905 established Japan as a geopolitical rival in Pacific. The increased awareness of Japanese power by the United States helped both to aid and inhibit the anti-Japanese agitation that was developing on the west coast.3 Local organizations mobilized to create anti-Japanese propaganda while President Theodore Roosevelt urged caution to prevent insulting the Japanese government. The following years brought the first federal legislation dealing specifically with Japan as well as the controversial “Gentleman’s Agreement”. During World War I immigration restriction was focused primarily on Germans, Bolsheviks, Communists, and anarchists. The post-war rise of American nationalism increased support for a broader and increasingly racist immigration policy. As part of this movement, the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization began to investigate issues surrounding Japanese immigrants in the United States. After conducting preliminary hearings in Washington D.C. during the summer of 1919, the Committee scheduled a more comprehensive investigation for California (the state with the largest Japanese population) the following year. The main topics of thee hearings were: was the “Gentleman’s Agreement” being adhered to by Japan?; Could Japanese immigrants be assimilated into American society?; and should Japanese immigrants be eligible for naturalization?

Japanese Hearings Come to Washington

In response to lobbyists and Washington Governor Louis Hart, the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization extended the scheduled 1920 hearings on the Pacific Coast Japanese question to the State of Washington. Local Japanese politics were not foreign to the Congressional committee or federal level politicians. They had received previous statements from prominent Seattleites such as businessman and publisher Miller Freeman, Presbyterian pastor Mark A Matthews, and local Japanese missionary U.G. Murphy. The chairman of the committee was also Washington State Congressman Albert Johnson, a long-time crusader for more restrictive immigration legislation. Johnson had a history of racial agitation in Washington State. As editor, he had long used his Grays Harbor newspaper to attack Asian immigrants and he pointedly supported a 1907 riot that forced hundreds of South Asians in Bellingham, Washington to flee the United States for Canada.4 Johnson also encouraged local anti-Japanese agitation at a Tacoma American Legion meeting less than one month before the 1920 hearings.5

Including Johnson, the committee contained fifteen members. All but six remained in California to conduct further investigation during the Washington State proceedings.6 The hearings commenced at 9:30 AM on July 26, 1920 in the federal courthouse in Seattle. The testimony continued in Seattle until July 29, at which point they were moved to Tacoma for a single day on August 2, returning to Seattle for the final day on August 3. The primary voices included were that of the Seattle Ministerial Union, American Legion and Veterans Welfare Commission, local immigration officials, farmers, and local Japanese. The hearings also included scattered testimony from organized labor and female citizens concerned about Japanese morality. Also in the transcript of the hearings is a vast quantity of statistics on the local Japanese community. Included are immigration data, birth rates, and complete listings of all Japanese businesses in and around Seattle. After the testimony, the record concludes with a summary of the Japanese situations in both Oregon and California.

Anti-Japanese League

Why did the hearings come to Seattle? Some speculated that Governor Hart’s term was nearly up, and the Republican-led committee timed the hearings to garner support for his November re-election bid.7 It was Seattle’s Anti-Japanese League, however, waged the campaign to extend the congressional hearings to Washington.

The League was primarily comprised of members of the American Legion, Veterans of Foreign Wars, and Washington State’s Veteran’s Welfare Commission (VFW). The Anti-Japanese League was founded in1916 by former Washington State legislator and director of the local United States Naval training facility, Miller Freeman. Freeman was the League’s president at the time of the congressional hearings. He had also been appointed to the head of the Washington State VFW by Governor Hart.8 Freeman had testified before the committee in Washington D.C. in 1919 and was asked by Chairman Johnson to solicit additional anti-Japanese witnesses. In the 1919 testimony, Freeman framed his animosity toward Japanese immigrants in the context of competition for control over the Pacific Rim: “To-day, in my opinion, the Japanese of our country look upon the Pacific coast really as nothing more than a colony of Japan, and the whites as a subject race.”9

Adding to this sense of conflict was the strong military presence at the Seattle and Tacoma hearings, which worried the Seattle Union Record, the city’s labor newspaper.

Another feature of the inquiry is the presence of a military group in the background that keeps in constant touch with Mr. Johnson or Mr. Raker of the committee. This group composed of men like Miller Freeman, Colonel Inglis, Philip Tindall, does not make a pleasant decoration for an inquiry on Oriental affairs-an inquiry that should be kept as far from military influence as it is possible to keep it.10

This statement made by Seattle Union Record Editor Harry Ault was powerful enough to command the notice of the congressional committee. Congressman Raker went so far as to confront Ault about his editorial statement, and to deny that there had been any closed-door meetings with military representatives.11

Yet despite the military context, Freeman’s testimony in support of restricting Japanese immigration was based almost entirely upon economic rationalizations. After introductory testimony by Governor Hart, Freeman was the first to give testimony to the congressional committee. First, he claimed, Japanese were taking jobs away from World War I veterans returning from Europe. This argument would be elaborated upon when Director of the Veteran’s Welfare Commission Colonel W.M. Inglis testified that Japanese at the Stetson-Post Mill Co. received twenty jobs that supposedly should have gone to veterans in the spring of 1919. When asked by Chairman Johnson what had happened when Japanese laborers were in competition with a group of veterans for twenty mill jobs Colonel Inglis responded: “The result was the Japanese were employed and the ex-service men were not.”12

The other chief concern voiced explicitly by Freeman and others was that Japanese immigrants were taking over certain business sectors from their Caucasian competitors. Freeman stated: “My investigation of the situation existing in the city of Seattle convinced me that the increasing accretions of the Japanese were depriving the young white men of the opportunities that they are legitimately entitled to in this State.”13 Shut out of local unions, Japanese had been forced into business, finding considerable successes primarily in agriculture and residential hotel ownership. These successes were the main source of agitation for the Anti-Japanese League, whose prominent members could no longer control the local Japanese population.

Seattle Star Promotes Anti-Japanese Agitation

Both in California and Washington, newspapers and newspaper men were prominent in creating anti-Japanese sentiment. The publisher of The Sacramento Bee, V.S. McClatchy, was perhaps the most outspoken anti-Japanese agitator in California.14 House Committee Chairman Albert Johnson had been in the newspaper business for two decades prior to the Washington State hearings, having published The Seattle Times, The Tacoma News, and The Grays Harbor Daily.15

The Seattle Star was the primary anti-Japanese voice in the Puget Sound area. In the weeks preceding the congressional hearings, The Seattle Star ran a series of articles that portrayed local Japanese in a negative light. One three-part series written by George N. Mills and beginning on May 19, 1920 was titled “The Japanese Invasion AND ‘Shinto, the Way of the Gods.’”16 From the beginning of the article, Mills expresses his desire to “…impress more emphatically on the mind of the American reader the certain disastrous consequences of future Oriental immigration, and why our present policies as regards certain Asiatics should be forever abandoned.”17 Mills describes the Shinto religion as the basis for life in Japanese culture and government, going so far as to say that, “religion and government in Japan have been one and the same in the past as well as the present.”18 Mills uses this premise to argue that any person of Japanese heritage who practices the Shinto religion will be ultimately devoted to the government of Japan. This idea was certainly on the minds of the congressional committee when they questioned Japanese witnesses about their loyally to Japan and willingness to perform military service for Japan or the United States.19 Mills continued the anti-Japanese agitation in his third installment when he stated that “If our present policies with Japan continue indefinitely, it will only be a matter of time when at best we will be no better than a subject race.”20

Beyond the Mills piece, The Seattle Star ran smaller anti-Japanese pieces on nearly a daily basis leading up to the hearings. ““Spy” Film is Killed by Japs”21, “Say Jap Choked White Woman”22, Charge Jap Stole White Wife’s Love”23, and “One-Third of Our Hotels Jap Owned”24 read some of the headlines between May and July of 1920. The Seattle Star was also quick to cover the protests by anti-Japanese organizations and their efforts to focus federal attention on the local Japanese question. This included appeals to labor groups to support anti-Japanese legislation, coverage of petitions by veterans groups to Governor Hart, and attacks on local ministers for their continued support of the Japanese.

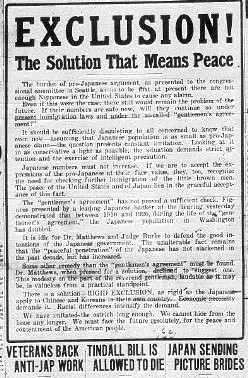

Although coverage from other local publications (The Seattle Times, The Seattle Union Record, and The Town Crier) was not pro-Japanese, the coverage provided was more balanced and less inflammatory. While The Seattle Star signaled its position with an inflammatory front page headline after the first day of the congressional testimony: “EXCLUSION! The Solution That Means Peace,”25 the traditionally radical _Seattle Union Record_ambiguously reported: “We withhold judgment concerning the testimony before the congressional committee of inquiry of Oriental affairs, until it is finished in Seattle.”26

Anti-Japanese Politics in City Hall

In the summer of 1920, the Seattle Star and the Anti-Japanese League’s exclusionary politics fused in a campaign against Japanese hog farmers. The campaign was one of the most overt attempts at limiting the livelihoods of Seattle’s Japanese during the time of the hearings. The Seattle Star reported that Japanese farmers were paying too high a price for restaurant swill (the primary source of sustenance for local hogs). The fear was that Japanese would price white farmers out of the swill market, and thereby drive white hog farmers out of business. Supposedly, once a monopoly had been established, the Japanese would escalate the price of pork products to recover the capital invested in the high-priced swill.27

Seattle City Councilman and Anti-Japanese League member Phillip Tindall was at the center of the campaign against Japanese hog farmers. Tindall proposed a bill that would change the way in which restaurant swill was collected. The Tindall bill called for a city-wide restaurant garbage collection contract. As a direct strike at the Japanese hog farmers, the Tindall bill specified that the garbage collection contract could only be entered by a citizen of the United States (a privilege not granted to Japanese immigrant farmers).28 If ratified, the Tindall bill would have virtually eliminated Japanese farmers from the hog business.

As part of the general anti-Japanese agitation, the sanitation and general operation of Japanese owned hog farms was also called into question. A letter to the editor of the Seattle Star penned by King County Health Officer H.T. Sparling complained that “The condition of some of these (Japanese owned) ranches is indescribable.” Nevertheless, Sparling went on to describe rat infested conditions and filthy meat being taken to the market for human consumption. In closing, Sparling stated, “I am strongly in favor of the ordinance introduced by Councilman Tindall and recommended by Dr. Bead, as it tends to centralize the industry and will make supervision easy.”29

The Tindall bill was passed by the Seattle City Council on June 21, 1920 by a vote of five to two. The bill was said to break up the Japanese “garbage collection monopoly” as well as add $50,000 to the city’s budget once a new collection contract was reached with a non-Japanese bidder.30 The garbage collection bill was seen as a potential trend setter for new bills that could further limit Japanese advances in other business realms. The Seattle Star editorialized, “We must stop the Japs at every opportunity we get. The Tindall bill is one of those opportunities.”31

Not all Seattleites agreed that the Tindall bill would be an effective or moral means of controlling Japanese commerce. _The_Town Crier gave the “…inside dope on the Tindall garbage bill, a measure that was camouflaged as one of sanitation but later came out into the open as intended primarily to put Japanese hog ranchers out of business.”32 This same piece from The _Town Crier_implicates local hog rancher I.W. Ringer (supposedly the only rancher with the capacity to bid on the garbage collection contract) as another driving force behind the Tindall bill. Less than a week after its initial passage, the Tindall garbage bill was vetoed by Seattle Mayor Hugh Caldwell. After supporters failed to bring the matter back to the City Council for a potential override, the Tindall bill died on August 1, 1920 (the thirty day deadline after the Caldwell veto).33

Japanese Americans Testify

A small yet interesting portion of the hearings took place on the second day of testimony when several Japanese immigrants and second generation Japanese Americans appeared before the committee. The most prominent member of the Seattle Japanese community to testify was Mr. D. Matsumi. Matsumi was the general manager of M. Suruya Company (dealing with the import and export of general goods), as well as the president of the United North American Japanese Associations. This organization branched to Montana and Alaska, independent from its counterparts in Oregon and California.35

Matsui was able to offer a very detailed census of the local Japanese population based on data his Japanese association had collected over the previous four years. The private census included complete data on Japanese children in the local school system, Japanese churches, hotels, and farms. The most complete data in the census record pertains to the birth and death rates of Japanese (and Chinese) in Washington State. Beyond the state records, there is also similar data collected from every major county in the state between 1910 and 1917, comparing the Japanese birth rate to that of whites in the same areas. At the end of this section of the census is a month by month record of birth and death rates from 1915 through early 1920. This section gives the best regional perspective as it includes, Washington, Idaho, Montana and Alaska.36 Mr. Matsui used this information to refute a frequent racist charge made against the Japanese: that they were reproducing at an alarming rate. The figures provided by the census proved this charge to be blatantly false. The committee was primarily concerned with how the census data was collected, but paid some attention to the condition of the educational system in regards to Japanese children.

Mr. Matsui chose not to directly refute charges brought against the local Japanese community by anti-Japanese witnesses. Instead, he portrayed Japanese immigrants as industrious Americans. In a written statement, he tried to give a historical perspective of Japanese in the region. Responding to accusations of unfair farming practices he reported, “According to these facts it seems to me that the Japanese farmer is more intensive in dairy farming than the other people engaged in the same business. The amount of milk produced per acre and the number of cows per acre on the farms operated by the Japanese is larger than that produced by others. In other words, there is less waste and the farming itself is conducted on a more intensive basis.”37

The five remaining Japanese to testify were not first generation, or Issei, immigrants. They were second generation, many of them American citizens, or Nissei. Reflecting the recent nature of Japanese immigration to the Northwest, they were all quite young, ranging in age from fourteen to twenty three. Chairman Johnson had described this portion of the hearings as an opportunity “to hear the leading Japanese representatives.”38 It is significant to note, then, that the Japanese community, rather than showcasing its own internal leadership, instead encouraged its youth to advocate for tolerance, understanding, and equal opportunity for all immigrants and their descendents. They offered themselves as living proof that, contrary to anti-Japanese arguments, Japanese immigrants and their children could assimilate.

Seventeen year old James Sakamoto, who would later become a community leader as editor of the city’s first English language paper for Japanese Americans, The Japanese-American Courier, was the last to testify. His older sister (who at the time was not even a resident of Washington State) also testified. All five statements from the young Japanese were brief, with questions directed at their education status, ability with the Japanese language, and whether the witnesses had any desire to return to Japan. The only diversion from the standard line of questioning took place during the testimony of James Sakamoto, at the time a seventeen year old student at Seattle’s Franklin High School. Sakamoto (who was born in Japan) was asked about his obligation to military service for Japan. He indicated that he would find a way to skirt this responsibility. Colorado Congressman William Vaile asked him, “…suppose you were required to render military service to the United States, what will be your position?” To which Sakamoto responded, “I will go in.”39 Sakamoto would remain true to this sentiment more than twenty years later when defending Japanese-Americans in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack. He stated that Japanese “will remain unswervingly loyal to the United States” and also the “first to uncover any saboteurs.”[40

Seattle Ministerial Union

One group intent on combating the anti-Japanese agitation was the Seattle Ministerial Union. According to the testimony of Seattle minister W.R. Sawhill, pastor of First United Presbyterian Church, “…there are about 250 protestant ministers in the city. They are all, in a way, members of the organization, but I suppose about 100 are paying and voting members.”41 Sawhill, along with Dr. Mark A. Matthews and missionary U.G. Murphy, were important voices before and during the congressional hearings. Both Matthews and Murphy had appeared before the Congressional Committee on Immigration and Naturalization previously in Washington D.C. and were familiar to lawmakers. According to Chairman Albert Johnson, Murphy was singled out as an exemplary voice, and asked to provide additional non-Japanese witnesses to vouch for the character of the local Japanese population.42 In June of 1919, U.G. Murphy had spoken on behalf of the Ministerial Union as part of a series of congressional hearings in Washington D.C. Murphy was clear that the Ministerial Union was against racially based immigration policies: “…it is the discrimination along race lines that causes the tension. Our naturalization law is based on the color scheme, the race line, and that is the offensive point.”43

Prior to the Seattle and Tacoma hearings, the Ministerial Union penned a letter to the committee requesting an investigation into the activities of the Anti-Japanese League and stating their positions on the Japanese question. In its letter dated July 24, 1920 (included in the testimony of W.R. Sawhill), the Seattle Ministerial Union was clearly opposed to any constitutional amendment limiting rights of Japanese Americans or immigrants. They also spoke in favor of unlimited admission of Japanese students as well as equal treatment for immigrants from all countries.44

Because of their history of steering large congregations on political questions and local elections, the Seattle Ministerial Union came under attack from anti-Japanese witnesses as well as The Seattle Star. Dr. Mark A Matthews was a favorite target of the Star, which pointed to his relationship with President Woodrow Wilson as reason to fear his influence on the local and national levels.45 Despite its origins on the West Coast as a Democratic Party movement, immigration restriction was politically a Republican crusade. Wilson, a Democrat, had twice vetoed the immigration legislation that was eventually passed in 1917.46

Dr. Mark A Matthews

Dr. Mark A Matthews was one of the most outspoken opponents of anti-Japanese agitation before and during the Congressional hearings. He was the minister of Seattle’s First Presbyterian Church which at the time boasted nearly a 10, 000 member congregation, making it the largest Presbyterian congregation in the United States (more than double the size of the second largest church). Because of the prominence of First Presbyterian, Dr. Matthews was elected as moderator of the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church, the national governing body of the Presbyterian denominations. This national position led to an association with United States President Woodrow Wilson. Dr. Matthews visited the White House on numerous occasions, and welcomed President Wilson as a guest for one of his sermons during a visit to Seattle.

Matthews had roots in the southern United States and was a proponent of the fundamentalist movement within the Presbyterian Church.47 He was very active progressive reformer in the local community, crusading against all of the “evils” of the city. In previous years, he had petitioned President Wilson regarding post-World War I treaties with Germany, labor issues and political appointments of his associates. Matthews had a history of swaying his massive congregation on political issues and was credited with helping oust former Seattle Mayor Hiram Gill in 1911.48

Matthews was staunchly opposed to radical labor groups such as the I.W.W., anarchists, and communists. Many of his letters contained anti-Semitic sentiments, accusing Jews of supporting radical left-wing causes. In one of his more colorful statements, Matthews advocated the deportation of thousands of Russian immigrants along with other communists and anarchists. “why,” he asked, “should we allow the gauze dress of American civilization to be destroyed by the torch of anarchy in the hands of these infernal enemy aliens?”49 As an opponent of organized labor, Matthews’s support of the Seattle Japanese community may have been an effort to weaken local unions. The Japanese had maintained solidarity with organized labor during the 1919 Seattle general strike, but almost all local unions excluded Japanese from their membership, and then fiercely competed with non-union Japanese businesses.

During his testimony in front of the congressional committee, Dr. Matthews’s objections to discrimination against Japanese immigrants were based mostly on issues of federal jurisdiction. He felt that any issue dealing with immigration was a treaty issue and that national legislation would only lead to further diplomatic problems.50 Perhaps as part of his anti-labor politics, Dr. Matthews expressed respect for the work ethic and business savvy he identified with Japanese immigrants. He suggested that their entrepreneurial activities made them model Americans. In response to California Congressman John E Raker’s question about Japanese taking over certain industries, Dr. Matthews responded, “Now, no Jap has ever taken over anything in Seattle, or will ever take over anything anywhere else in this country… They bought it, and if you object to a Japanese citizen or immigrant buying a fruit stand, an American sold it to him. Now if it is not right for the Jap to own it, why did the infernal, yellow-backed American sell it to him?”51

The Quiet Voice of Organized Labor

In comparison with the outspoken testimony of ministers, legionnaires, farmers, and immigration officials, organized labor was relatively quiet during the congressional hearings. Two union officials from Tacoma gave brief testimony. One was Thomas A Bishoff, secretary of the Tacoma Cooks’ and Waiters’ Union, and the other H.C. Pickering, secretary of the Tacoma Barbers’ Union. Both were relative outsiders to the general feeling of local organized labor and admitted most of their testimony was personal feeling or hearsay.

Both Bishoff and Pickering were questioned about Japanese participation in their respective industries in the city of Tacoma. When asked to speculate about what might happen if Japanese barbers were to attempt to open shops in the Tacoma harbor area (where there were only white barbers), Pickering responded: “Now down on the harbor, down where there are no Japanese barbers, there is a prejudice down there.”52 He indicated that there would likely be considerable strife if Japanese barbers attempted to locate themselves in the harbor area of Tacoma.

According to Chairman Johnson, requests for labor representatives from the Seattle area went unanswered for unspecified reasons.53 A key feature of the testimony from the labor representatives was a sentiment that Japanese were only a limited threat to the laboring class. Chairman Johnson expressed this point of view explicitly: “Now, we have been confronted with statements in this record to the effect that labor in Seattle had ceased to object to the admission of the Japanese on the ground that he had ceased to become a competitor of labor itself and was a competitor of the small business man.”54

Japanese immigrants originally came to the Pacific Northwest in the late nineteenth century under the recruitment of the Great Northern Railway Company. Early immigrants chiefly worked as laborers for the railroad or lumber companies.55 By the time of the Seattle and Tacoma immigration hearings, the climate of the Japanese workforce had changed drastically. In 1920, a large percentage of the Japanese in the Seattle area were engaged in farming or businesses such as restaurants, hotels, groceries, laundries, and barber shops. The labor movement that had been such a pivotal factor in the nineteenth century Chinese exclusion was dealing with a much different situation in the Japanese. Though excluded by organized labor, the Japanese had formed their own unions, often times abiding by many of the same regulations as their mainstream counterparts.56 This voluntary conformity may have been another potential factor in the lack of organized labor opposition. The Japanese had demonstrated their willingness to be loyal union members. Abiding by the same pay scales and shop standards as white unions meant that Japanese labor would not under-sell white labor. Although only officially recognized in the machinists and timber workers unions, members of Japanese unions had also shown their solidarity by refusing to be scab workers during the 1916 longshoremen’s strike and the 1919 general strike.57

Harry Ault testifies

“Who is this E.B. Ault that submitted his liberal, temperate and considered views on the Japanese question this week before the immigration committee? Can it be possible that he is the editor of that exponent of wild-eyed radicalism, The Union Record?”58

–The Town Crier, August 7, 1920.

Some of the most interesting testimony took place on the final day of the congressional hearings in Seattle. Erwin B. (Harry) Ault was the final witness to testify. In one of the longer statements throughout the proceedings, Ault cautiously spoke for the Central Labor Council of Seattle. Ault took a purely economic stance on the question of Japanese immigration and naturalization. Although he opposed future “Asiatic” immigration, he lobbied for equal rights and pay for all Japanese workers already in the United States. He expressed that any limitation on the earning power of Japanese laborers would only be detrimental to the general living standards of the American worker.59 He presented the marginalization of Japanese labor as a tool used by business owners to lower the wage scale for workers of all races. Ault was insistent on distancing himself and organized labor from any racial element in the Japanese question: “I say any prejudice, simply because a man’s skin is dark or fair-I don’t think that is a fair estimate of a man’s ability or capacity or usefulness to society or his right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”60

Ault was the only pro-Japanese witnesses to not condemn intermarriage between whites and Asian peoples. After some pointed questioning by a seemingly shocked Congressmen John Raker who asked Ault, “You would leave the young people of the United States at liberty, without any law, to choose their mates, to intermarry as they see fit?” Ault responded, “Absolutely.”61 The Town Crier, which associated union advocacy with simple-minded bigotry, commented on Ault’s testimony: “Perforce, he wonders why Mr. Ault cannot apply some of the same common sense, clear thinking and tolerance to the consideration of other matters that occupy the attention of The Union Record.”62

Afterward

Congressman Johnson went on to co-author the 1924 law that drastically curtailed most immigration to the United States considered non-white, including Japanese. Seattle’s anti-Japanese forces— particularly Miller Freeman,the Anti-Japanese League, The Seattle Star, and, increasingly, Teamsters union—continued their agitation for another generation helping to set the stage for the persecution and internment of Washington’s Japanese American population during World War II.

But Washington’s hearings on Japanese immigration did not just signal a rising tide of anti-immigrant racism. They also helped inspire a young James Sakamoto to promote Japanese American citizenship claims. The year after the hearings, Sakamoto co-founded the Seattle Progressive Citizens League in 1921, a predecessor and model for the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). His leadership and the efforts of other Nissei activists were part of a broader movement against anti-Japanese and anti-Asian racism that would run counter to American exclusionary politics for the rest of the century.

Copyright © Doug Blair 2006

HSTAA 499 Summer and Spring 2005

1 The Seattle Times. July 26, 1920. Pg 5.

2 Ibid. Pg 1 & 5.

3 Higham, John. Send These to Me: Immigrants in Urban America. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore and London. 1984: Pg 50.

4 Mae Ngai. Impossible Subjects: illegal aliens and the making of modern America. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2004. pp. 48, 288.

5 The Tacoma Daily Ledger. July 2, 1920. Pg 4.

6 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Japanese Immigration. Hearings before the Committee on immigration and naturalization, House of representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, second session. Washington, Govt. Print. Off., 1921: Pg 1056.

7 Magden, Ronald E. Furusato: Tacoma-Pierce County Japanese, 1888-1988. R-4 Printing Inc. Tacoma, WA. 1998. Pg 61.

8 Neiwert, David A. Strawberry Days. Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. New York, New York: Pg 57.

9 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Percentage Plans for Restriction of Immigration, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, first session. Washington. Govt. Print. Off., 1920: Pg 230.

10 The Seattle Union Record. July 27, 1920: Editorial Page.

11 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Pg 1436.

12 Ibid. Pg 1097.

13 Ibid. Pg 1062.

14 Gulick, Sidney Lewis. Should Congress Enact Special Laws Affecting Japanese? New York, New York. National Committee on Japanese Relations. 1922: Pg 85.

15 Dictionary of American Biography. Supplement Six. New York, New York. Scribner. 1980. Pg 320.

16 The Seattle Star. May 19, 1920. Pg

17 Ibid.

18 Ibid.

19 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Pg 1201.

20 The Seattle Star. May 21, 1920. Pg 17.

21 The Seattle Star. May 26, 1920. Pg 16.

22 The Seattle Star. June 1, 1920. Pg 16.

23 The Seattle Star. June 3, 1920. Pg 1.

24 The Seattle Star. July 1, 1920. Pg 15.

25 The Seattle Star. July 27, 1920. Pg 1.

26 The Seattle Union Record. July 27, 1920. Editorial Page.

27 The Seattle Star. June 25, 1920. Pg 8.

28 Ibid.

29 The Seattle Star. May 27, 1920. Pg 7.

30 The Seattle Star. June 22, 1920. Pg 2.

31 The Seattle Star. June 26, 1920. Pg 6.

32 The Town Crier. August 21, 1920. Pg 4-5.

33 The Seattle Star. July 27, 1920. Pg 1.

34 The Seattle Times, July 27, 1920: Pg 8.

36 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, Pg 1187-1189.

37 Ibid. Pg 1173.

38 Ibid. Pg 1148.

39 Ibid. Pg 1201.

40 Neiwert, 2005. Pg 119.

41 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Pg 1211.

42 Ibid. Pg 1404.

43 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Percentage Plans for Restriction of Immigration, House of Representatives, Sixty-sixth Congress, first session. Washington. Govt. Print. Off., 1920: Pg 82

44 Ibid. Pg 1210-1211.

45 The Seattle Star. May 18, 1920. Pg 1.

46 Higham. 1980. Pg 52.

47 Russell, C. Allyn. Journal of Presbyterian History, Vol 57, Number 4 (Winter, 1979). Pg 446-466.

48 Berner, Richard C. Seattle 1900-1920, From Boomtown, Urban turbulence, to Restoration. Charles Press, 1991. Seattle, Washington. Pg 118.

49 Matthews, Mark A. Mark A. Matthews Papers, University of Washington Special Collections, Box 5. Personal Letter to President Woodrow Wilson, November 26, 1919.

50 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Pg 1083.

51 Ibid. Pg 1090.

52 Ibid. Pg 1390.

53 Ibid. Pg 1387.

54 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Pg 1417.

55 Berner, 1991. Pg 67.

56 Frank, Dana. Race Relations and the Seattle Labor movement, 1915-1929. Pacific Northwest Quarterly, Number 86 (Winter 1994⁄1995). Pg 40.

57 Berner, 1991. Pg 69.

58 The Town Crier. August 7, 1920. Pg 4.

59 United States. Congress. House. Committee on Immigration and Naturalization. Pg 1424.

60 Ibid. Pg 1421.

61 Ibid. Pg 1427.

62 The Town Crier. Aug 7, 1920. Pg 4.

%20250.jpg)