On December 17th, 1944 U.S. Major General Henry C. Pratt announced that beginning January 2nd, 1945, the federal government would officially end the exclusion order that prevented Japanese and Japanese-Americans from returning to the West Coast following their release from World War II internment camps.1 His announcement contributed to a fiery debate over Japanese and Japanese-American “resettlement”—an idea that many in Seattlesupported, but that also had strong opposition. This essay will look at both sides of the resettlement debate in Seattle —which one historian has called “ Seattle ’s greatest racial problem during World War II”— by focusing on which groups took anti- and pro-Japanese-American stands, and how the media portrayed this debate.2

Before Pearl Harbor, there was a significant and prosperous Japanese and Japanese-American community in the Pacific Northwest. Though white racism limited their job opportunities, many Japanese and Japanese-Americans found relative success as entrepreneurs and business owners, particularly as farmers and hotel owners and managers. There were also many young Japanese and Japanese-Americans that were highly educated. Japanese and Japanese-Americans founded and actively participated in organizations such as the Japanese-American Citizens League (JACL) and many churches in the community. Through the JACL, Japanese and Japanese-Americans promoted civil rights more through community education and mutual aid and less through confrontational politics or protest.

With the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December of 1941, the United States government began to investigate and arrest leading Japanese and Japanese-American citizens, who they suspected of espionage. Despite finding no evidence of a feared West Coast espionage network, President Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which authorized the removal of 110,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans from the west coast to ten inland internment camps. In January, 1942 more than 7,000 Seattle area Japanese and Japanese-Americans were forced from their homes and sent to the camps.

The story of the removal and incarceration of Japanese and Japanese Americans in internment camps during World War II is well documented elsewhere. Less well known is the role that local groups on the West Coast played in justifying or challenging internment, and how, once Japanese and Japanese Americans entered the camps, these groups fought over whether Japanese Americans would return home.

For personal stories about this topic, see the interviews inDensho: The Japanese-American Legacy Project

Anti-Japanese Organizations

During internment, various anti-Japanese groups formed up and down the West Coast. In Seattle , the two most prominent anti-Japanese groups were the Remember the Pearl Harbor League (RPHL) and the Japanese Exclusion League (JEL). Though they formed during the war, their most active periods, at least according to newspaper accounts in the Seattle Times, Seattle Post Intelligencer, and the Seattle Star, were during the debate over resettlement at the end of 1944 and in early 1945.

The anti-Japanese groups used methods such as flyers and word of mouth to gain members. They also used newspapers to generate publicity by writing letters to the editors. The groups’ leadership and members came mainly from organized labor, veteran’s organizations, and agricultural interests who felt threatened by competition with Japanese and Japanese-Americans. Through their political connections, they were able to get partial support fromSeattle’s mayor, Washington State ’s governor, and its politically powerful Congressmen—Warren Magnuson and Henry “Scoop” Jackson. These groups’ leaders used their public meetings to preach an anti-Japanese ideology that while supposedly about American national security on the surface, often suggested that issues of race and economics were driving opposition to Japanese and Japanese-American return.

A large organization opposed to Japanese and Japanese-Americans resettlement was the Japanese Exclusion League, a group founded after World War I which worked in coalition with the American Legion. The League shared many of the same beliefs as the RPHL. Art Ritchie, a member of the Japanese Exclusion League, wrote a letter Senator Magnuson in January 1945 hoping to get an amendment to the Constitution to prevent Japanese immigrants from becoming citizens, and invited the Senator to join the JEL.3 The League consisted of many leading Seattle citizens from organizations such as Native Sons of the Golden West, the American Legion, farm leaders and women’s clubs. These types of leagues, which were formed in the beginning of the war, inspired the founding of similar groups in other areas near Seattle .4

The Remember the Pearl Harbor League was a group of farmers and businessmen mainly from the Auburn valley area. They were an anti-Japanese group that protested the resettlement of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans back to the west coast. In a pamphlet issued by the group, they argued first and foremost that all Japanese were “a menace”: “The Japanese were a menace until removed, and will become a menace again when returned. The Japs must not come back.” They also accused American-born Japanese of disloyalty because Japanese children were supposedly taught Japanese culture before American culture. They also claimed that Japanese and Japanese-Americans formed potential “Japanese Colonies” in the U.S. , which they referred to as “The Black Dragon.” There is no evidence of widespread Japanese and Japanese-American secret societies, though the Remember Pearl Harbor League may have been loosely associating racist myths about Chinese Tongs with Japanese-Americans. The group’s pamphlet even advocated amending the Constitution to deprive Japanese and Japanese-Americans of citizenship rights: “On the sole ground of disloyalty, all Japanese should be removed from the United States and its territories.”5

Nifty Garrett, a prominent businessman in the South Puget Soundarea, was a huge supporter of the Remember Pearl Harbor League. He owned a local newspaper in Sumner called the Standard. After the Japanese and Japanese-Americans were given word they could return home he published “OUR OBJECTIVE: BANISH JAPS FOREVER FROM THE USA” on the front page of his paper for 30 months. The League’s presence in the Sumner area was very strong: it had 65 members and no local opposition. In December of 1944, in response to the War Department’s decision, the League grew stronger and Nifty called a meeting to establish a fourth branch of the RPHL. This time, however, the League ran into some opposition, with defense worker R.S. Bixby calling them “cowardly, selfish, and guilty of fomenting racial hatred.”6

Historian Ron Magden has investigated the activities of the RPHL in the Puget Sound and concluded that support was uneven. In Seattle , the League failed to establish a branch chapter. In areas in the South Puget Sound, such as Puyallup , the League found considerable support. Some members drew a distinction between immigrant and American-born Japanese Americans, opposing the return of the older generation, while acknowledging that the American had the right to live wherever they liked. 7 In Bremerton , shipyard workers and Navy veterans formed their own RPHL, and boasted members that one newspaper described as “highly in favor of the league’s ideals.”8

The anti-Japanese groups had to defend themselves against various charges. Critics claimed that the main goal was to keep Japanese out because they wanted the farmland that the Japanese farmers had owned. It seems like the League came up with these reasons to cover the actual reasons that they did not want Japanese and Japanese-Americans to return.9 The main reason for the formation of this Remember Pearl Harbor League was economics. These farmers and businessmen from the Auburn valley feared the return of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans because of the economic impacts it would cause them. The Japanese and Japanese-Americans had been prosperous farmers and businessmen before the war. In the minutes of a Remember Pearl Harbor League meeting, they acknowledged, “we are accused of having a money interest in this business; but the WRA (War Relocation Authority) has spent much more money than we in putting out propaganda publications at governments expense.”10 The government did not have a moneymaking interest in the return of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans: they were putting out publications to educate the public, freely, unlike in the League where members had to pay a fee to join.

Critics also claimed that they were more interested in dues than anything else. Opponents of groups like the Remember Pearl Harbor League used newspapers to warn people not to join anti-Japanese organizations that required a fee, saying that they were just out to make a quick buck. They also tried to stigmatize anti-Japanese groups as racist by comparing them to Hitler and the Ku-Klux Klan. One resettlement advocate told the _Seattle Times_“Anyone/member of an organization based on racial hate is laying the ground work for a program like Hitler developed.”11

Pro-Resettlement Advocates

There were many individuals and anti-Japanese organizations at the time, but there were just as many individuals and pro-Japanese organizations fighting for the rights of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans. Some of these groups included the Seattle Council of Churches, American Friends Service Committee and the Seattle Civic Unity Committee.

The Seattle Council of Churches was an important organization with the return of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans to the west coast. The Council of Churches helped by first assisting the Japanese and Japanese-Americans in its struggle to re-establish themselves back onto the west coast. They educated the city on Christian virtues of hospitality and acceptance, hoping it would cause people to accept the Japanese and Japanese-Americans back. The Council also chastised the Governor for all his anti-Japanese remarks and well as other anti-Japanese organizations. The council established hotels to function as temporary housing and it also created the United Church Ministry. The United Church Ministry provided many services to the returning Japanese and Japanese-Americans. It set up a program to provide jobs, housing, and social services including counseling, medical care, social and recreational events, legal services and serving as a liaison between Japanese people and government welfare agencies. The Council also set up a program in the community by sending out enlistment cards. People could sign up to sponsor and provide temporary or permanent housing to the Japanese and Japanese-Americans. This program was overwhelmingly successful, many people were expressing their willingness to accept and bring back the Japanese and Japanese-Americans to the west coast. The Council’s ability to bring the city together was inspiring to many independent groups, who decided to join in with the Council rather than go a separate way. With all the unity in the community, anti-Japanese groups were finding it more difficult to survive.12

The Civic Unity Committee also helped promote and coordinate local Japanese and Japanese-Americans’ resettlement. The Committee was established in February of 1944 partly to help ease racial tensions related to increased African American migration during the war. But the Committee also, unlike similar committees in other cities in the North, protected Japanese and Japanese-American rights upon their return to the West Coast. Before the Japanese resettlement, the CUC was one of several organizations which publicly fought the anti-Japanese groups. They fought to get anti-Japanese pamphlets entitled “The Japanese Must Not Come Back” off of newsstands. They also criticized the Governor for his remarks opposing the Japanese and Japanese-Americans and his wild claims about secret Japanese societies. When the Japanese and Japanese-Americans returned in 1945, the CUC received partial credit because of their work to promote a tolerant public policy and political culture.13

The American Friends Service Committee was another group whose goal was to help the returning Japanese and Japanese-Americans. This group was concerned with the over-all welfare of the Japanese community. One member of this organization was Floyd Schmoe, a University of Washington professor of Forest Biology. Schmoe frequently visited the Minidoka internment camp inIdaho to investigate camp conditions and internees’ experiences. In March of 1945, after the decision by the government to resettle Japanese and Japanese-Americans on the West Coast, he “reported that the mood in the camp was grim and confused.” The Japanese and Japanese-Americans were confused and scared because of all the resistance still in the Seattle area, even though it was getting better and calming down. The Japanese and Japanese-Americans in the camp were becoming more resistant because of the news of the camp closing; many did not want to leave for fear of the growing hostility toward them on the West Coast. These fears caused many Japanese and Japanese-Americans to move to the east and to the mid-west instead of going back to Seattle .14 During the summer of 1945, special railroad cars brought the Japanese and Japanese-Americans back to the Puget Sound area, where many found that their homes had been vandalized by Seattle hoodlums, sometimes with death threats spray-painted onto their garages.15

Mobilizing Resistance to Resettlement

Resettlement advocates may have been well organized, but their victory was not inevitable, since local anti-Japanese groups had some very powerful allies. Groups like the JEL and the RPHL worked with more established organizations like the American Legion, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, organized labor, and their allies in political office.

In 1943, the Seattle Chamber of Commerce and Congressman Henry Jackson jointly expressed interest in potentially using Japanese internees as forced labor to address the wartime shortage in farm labor. From 1943 through 1944, Congressman Warren Magnuson, a longtime supporter of the Teamsters Union, fed newspapers information meant to incite fear of resettlement, lobbied the U.S. military against resettlement, and warned ominously that his constituents were “violently opposed” to resettlement.16

In October 1944, as some evacuees began returning but two months before the U.S. military announced its support for total resettlement, opposition to return spiked. As previously mentioned, supporters in Bremerton decided to form their own branch of the RPHL to fight the return of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans. They looked to groups like the Japanese Exclusion League and the Remember Pearl Harbor League to form their own league. In theSeattle Post Intelligencer on October 7th, 1944, a Seattle attorney, E.D. Phelan, recommended that the new group “work for an amendment to the United States constitution which would revoke the American citizenship of all Japanese.” That same article also included opinions of people who merged the interests of veterans, farmers, and truck drivers. J.L. Anderson of Enumclaw, a member of the RPHL, linked Japanese and Japanese-American economic success with World War II. “Japanese in our territory worked every day during the depression because they accepted $1.50 a day –and gave 25 cents of that to a Japanese foreman, assertedly now a captain in the Japanese army, who send the money to Japan . Those two-bit pieces are now punching holes in our boys.”17

Local representatives of the Teamsters Union were particularly prominent in their support for internment and opposition to resettlement. Their union locals were both racially exclusive and deeply hostile to Japanese American farmers’ tendency to employ Japanese American truck drivers to deliver their produce instead of all-white union truckers. And with Dave Beck at their head, the Teamsters were also one of the most powerful political forces in a heavily union town. John T. Steiner, secretary-treasurer of a local Teamsters Union told the Seattle P-I that “The Teamsters are campaigning to banish Japanese for the entire Pacific Coast .”18 Leland Burrows, acting director of the U.S. government’s War Relocation Authority, which would oversee resettlement, complained about the Teamsters’ “widespread attempt to drive these people from employment in the produce business.”19 For a while, the local ACLU even considered filing an anti-trust lawsuit against the Teamsters and the Northwest Produce Association for their anti-Japanese politics. A report by the Church Council of Greater Seattle noted that since internment,

Some of the more lucrative businesses in which Japanese had been fairly solidly entrenched are now partially or completely closed to them. The Teamsters Union and its closely affiliated organization of owners completely excludes them from the dry cleaning industry… and the potential competitors of the Japanese are able to reduce to a minimum their effectiveness in becoming established in the wholesale and retail produce business… Those businesses sold at the time of evacuation have been found to be remunerative, and the present owners are not interested in relinquishing them.

Racial animosity fueled this sense of economic competition. Teamsters leaders suggested doing a mass mailing to the public of a statue or picture of General McArthur with the tag of “number one Jap-hater”—an idea McArthur found personally repellant.20 And in a meeting of anti-Japanese Groups with city leaders and a U.S. general overseeing resettlement in 1945, Charles Doyle, the head of Seattle’s Central Labor Council, issued a not so veiled threat that resettlement would result in lynching: “you bring them back, we won’t be responsible for how many are hanging from the lamp posts.”21

Doyle was not alone in his threats. On December 18, 1944, when the government announced its resettlement policy, Benjamin Smith, the president of the Remember Pearl Harbor League, went public with his affiliated groups’ opposition in a way that darkly hinted at the possibility of vigilante violence. The Seattle Times reported that the “League declared the Japanese still are dangerous to the war effort, and added that his organization has pledged 500 persons not to sell, lease or rent farms, homes or stores to the returning evacuees. He said that ‘further steps’ might be taken.” That same newspaper also quoted him saying “We see no reason why they should be allowed to return to the Coast, especially when they are getting along all right where they are.”22 In the Seattle Star on December 18th, 1944, Smith was quoted saying that “The league is definitely opposed to the return of the Japanese, and will do every legal thing in our power to prevent it. No Member of the league will do any violence to any Japanese, but we gravely fear that irresponsible persons may do them some harm.”23

William Devin, Seattle ’s Mayor, initially opposed resettlement but later backtracked. On September 20th, 1944 three months before the federal government’s announcement, he said that he did not want to be the first to hire a Japanese or Japanese-American person in a city-government job. He “felt it would be better for these people to mingle with the community, to see how the community might take them, before their employment by the city.”24 Mayor Devin somewhat backed down when the WRA announced its resettlement plans. On December 18th, 1944, Devin released a statement that “promised ‘full protection’ for all returned Japanese.” He wished that the citizens of Seattle “put into effect those principals of democracy which we are all so justly proud as Americans. As the mayor of this city, it is my duty to see to it that all of our citizens, regardless of race or color, are given equal protection under the law and that I intend to do.” Either feeling pressure from on high, or an ability to use the Army’s declaration as political cover against his anti-Japanese allies, Devin finally went on record saying he was willing to accept the Japanese and Japanese-Americans back.25 He went on to encourage the Civic Unity Committee to take a leading role in minimizing conflict over resettlement.26

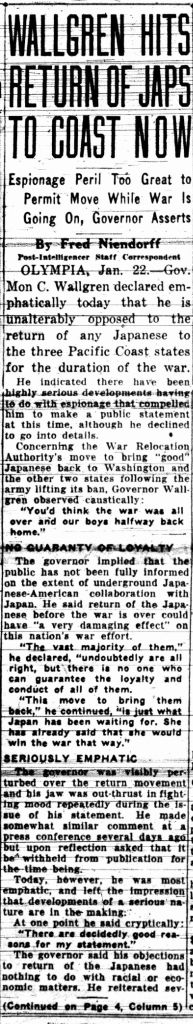

But just as Devin was backing down, Governor Mon C. Wallgren stepped up to oppose resettlement. The Seattle Post Intelligencer reported on January 23rd, 1945 that he “declared emphatically that he is unalterable opposed to the return of any Japanese to the Pacific Coast states for the duration of the war.” Governor Wallgren frequently accused Japanese and Japanese-Americans of disloyalty, but never provided evidence to his claims. The Seattle Post Intelligencer reported a month earlier that the Army believed that “there was no longer any question of military security, and that loyal persons of Japanese descent would be permitted, if they so desired, to return to their former homes.” When the Japanese and Japanese-Americans had been given the official word that they were able to return, the Governor was reportedly “visibly perturbed.” Anticipating his opponents’ criticism, the Governor, according to the Seattle PI, said “His objections to return of the Japanese had nothing to do with racial or economic matters. He reiterated several times that they were based purely on military considerations.”27

All of this sent the community mixed signals: the army told the public that everything was fine, but their local Governor was saying the opposite. What were people to think? In response to anti-Japanese groups, resettlement advocates used local newspapers as a vehicle to get their position out into the community about the issue of the returning Japanese and Japanese-Americans. The next part of this essay will examine the two sides of the debate which appeared in newspapers beginning in the end of 1944 mainly December through January of 1945.

Citizens Speak Out: The Newspaper Debate

Pro-Japanese groups, after Wallgren’s anti-Japanese statement, wrote a letter to the newspaper telling the governor to revoke his statement and stand behind the decisions of the military.28 This statement from the Governor also erupted onto theUniversity of Washington Campus . On January 24, 1945 a day after the statement, University of Washington Daily writer, Julie Legg, published an editorial condemning the Governor’s statement. In her editorial, Julie pointed that Washington State ’s leadership on this issue could set the mood for other states on the West Coast. “Here would be a great chance for the state of Washington to stand for the democratic ideals upon which our nation is supposedly based. Here would be a chance for our state to take the lead and see that these loyal Americans are given just treatment.” She criticized the Governor for making such a hasty statement, for second-guessing the FBI and saying that “citizens of this state who favor the return of our Japanese fellow citizens do not know of or cannot comprehend the works of sabotage and espionage that these people commit.” “Mr. Wallgren,” she concluded, “can’t we be fair and allow them to return to their homes?” The next day there were several letters to the editor printed in the Daily commending the newspaper for having the courage to print this article. From those letters it seems clear that many people on the University of Washington campus supported the return of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans.29

As the controversy raged several newspapers encouraged readers to voice their opinions about whether Japanese should be allowed to return. On December 18th, 1944 the _Seattle Star_—which gave the anti-resettlement forces some of their most positive press—interviewed people at random in the downtown area. One man said that if the army approved of Japanese-American return to the West Coast, then there should be no debate on the issue: “After all, the Japanese-Americans as they are termed, are in actuality American-Japanese, and as such are citizens under our constitution. It is not a question of sentiment, but of constitutionality.” Betty Lou Huffy did not respond in the same way, “I do not think the Japanese-Americans should be allowed back here, ever. There are so many reasons they should not it would take me an hour to list them.” Richard Messmer thought that the Japanese should be allowed to return to the West Coast: “After all, many of them have proved their loyalty by serving in our army. However I am against the return of those born in Japan.” Mrs. Bertha Saltee, however, said: “Never bring the Japs back. Both my son and son-in-law are in the service, fighting the Japs, and they would not want them back. You can’t trust a Jap; he’ll stab you in the back every time.”30

Letters to the editor also provide a window into citizens’ various views on the resettlement issue. J. Logan of Bremertonwrote to the Seattle Post Intelligencer on December 30, 1944 expressing that he felt safer without the Japanese on the west coast because saboteurs could be more easily spotted since there were suppose to be no Japanese on the coast.31 Bill Hubbs from Seattlefelt that he didn’t see how Japanese in America could remain loyal toAmerica while their family was living in Japan , the enemy. He really did not mind the Japanese return but was not really for it either.32 G.J. Helland from Snohomish also felt it was better the Japanese stay away from the west coast. He argued that the west coast shouldn’t have to “hinder our manpower shortage by having to be on the alert for underground work by some disloyal Japanese.” He was a supporter of the Governor, wishing to keep the camps open, because if the Japanese are let back into the west coast the will prolong the war.33 Thos G. Sutherland, M.D. from Auburn saw the Japanese and Japanese-Americans return to the west coast as not being beneficial. He stated that it would increase the housing shortage, endanger the war industry and allow for espionage and sabotage. He wanted to remove the War Relocation Authority and let the army take over until the end of the war.34

As these letters attested, debates over race and citizenship had a sharper focus at a time of war rationing and economic scarcity. On January 10th, 1945 the Seattle Star published an article which explained what some people were beginning to face with the return of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans. The article was about eight war families who had been living in a house owned by a Japanese-American. Upon his return from the camps, he wanted his house back for himself and his family. The occupants protested that it was not easy to find housing at the time, while the Japanese-American owner countered that it would be even harder for him and his family to find a place to stay than it would for a white family. The white tenants thought that he was being unfair to the war effort because their hard work was much needed for the war.35

Many people in the community also voiced their pro-Japanese opinions on the issue of the return, and described the anti-Japanese groups as un-American and not helpful in the war effort. Mrs. Lynn Brannan from Auburn wrote to the Seattle Post Intelligencer on December 30, 1944 “the ‘Remember Pearl Harbor League’ is a stab in the back to our men on the battle fronts, because it is un-American. I say it is un-American because it proposes to judge a group of Americans as being disloyal without a fair hearing and on the grounds of the religious beliefs of their kin in another country.” She then went on to say that the anti-Japanese groups are using this opportunity to be racist and take advantage of its economic opportunities, which seemed to be very true in some anti-Japanese organizations.36

On December 18th, 1944 many people are featured in theSeattle Star having positive reactions to the decision to allow the Japanese and Japanese-Americans back. “Arthur G. Barnett, Seattleattorney and head of the Seattle Council of Churches social welfare committee, today expressed great pleasure at the news that the Japanese-Americans are to return.” Floyd Schmoe, a long time peace activist and university professor, is another Seattleite who expressed his support for Japanese and Japanese-Americans: “Anyone now opposing the return of the Japanese-Americans to the West Coast is in effect now opposing our war department. Most of the opposition to return of the Japanese-Americans arises out of the hope of economic advantages or out of race prejudice and is usually cloaked as pseudo-patriotism.” Schmoe was also quite pleased with the decision because his daughter was married to a Japanese-American; he hoped they would now move back to Seattle . Dr. Lee Paul Sieg, President of the University of Washington , made a statement that day that “Returning Japanese who wish to study at theUniversity of Washington will be encouraged to do so.” He also stated that the University would not be able to control the actions of all people but “those desiring to study at the university will be accepted as students in accordance with the regulations governing the admission of any student.” 37 Harold V. Jensen, president of the Seattle Council of Churches was thrilled the day the WRA made the announcement of the return of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans. He said “the council at a meeting this afternoon will discuss specific plans to help the returning Japanese with any problems they may face such as housing and employment. Now that the military emergency which caused the evacuation has passed, revocation of the order is a much needed vindication of democracy.”38

Many others showed sympathy towards the Japanese. Four women from Seattle wrote in to the Seattle Post Intelligencer on January 26, 1945 expressing that American-citizens of Japanese ancestry have had to suffer more than any other group in the country. “They have not only been deprived of their civil and constitutional rights but have also been socially and economically ostracized and are all too often regarded by their fellow Americans with unwarranted suspicions and hatred.”39

A December 14th, 1944 editorial in the Seattle Star, titled “It’s Time to do Some Thinking On Nips’ Return” seemed to begrudgingly acknowledge the citizenship rights of Japanese-Americans, but still framed their return as a problem. The editorial stated that “Legally, there is nothing now which prevents their return-in fact, as far as the legality of the matter was concerned, it was impossible for the army to have evacuated them in the first place. They are American citizens and as such are entitled to ‘park’ any place in the country.” In the editorial, the writer also says that the WRA had interviewed many of the Japanese and Japanese-Americans that settled inSeattle recently, by permit, and that supposedly none of them wanted to stay because of the public reaction they were getting. Much of the public reaction is the propaganda being issued by the anti-Japanese leagues such as the Remember the Pearl Harbor League. In the end he stated, “The question of what to do with the Japanese seems to be facing us. And somebody had better do some serious thinking about it.”40

The three local newspapers Seattle Times, the _Seattle Star_and the Seattle Post Intelligencer all covered the issue in different ways. The Seattle Times covered resettlement as a positive event, but perhaps to prevent the incitement of racial tension, did not publish as much about the issue as the city’s other two daily papers. The Seattle Star was the first to start the anti-Japanese agitation, and it gave the issue a lot of coverage, looking to the community for comments on the issue and providing a great deal of information on anti-Japanese organizations. 41 _The Seattle Post Intelligencer_provided the area with the most coverage on the issue. It gave the community many different views on the matter with letters to the editor, coverage of government officials and both anti- and pro-Japanese organizations.

In the first months of 1945 as the Japanese and Japanese-Americans began to return, the controversy faded from the pages of the press. Many efforts had been taken and most citizens had decided to accept the Japanese and Japanese-Americans back into the community. The government had begun a publicity campaign on the heroism of Japanese-American Soldiers, which helped to ease a lot of the anti-Japanese fears.42 Anti-Japanese organizations failed to prevent the military from allowing resettlement, and failed to broadly influence public opinion. Their campaigns showed how widespread Anti-Japanese hostility in the Seattle area was, but at the same time how shallow it was. In the summer of 1945 anti-Japanese groups throughout the Puget Sound began to dwindle. The Sumner branch of the Remember Pearl Harbor League no longer was holding public demonstrations and their leader Nifty Garrett sold his SumnerStandard and retired to Missouri .43 Their failure testified to the power of civil rights organizations to advance racial tolerance even in a time of war.

© Copyright Jennifer Speidel 2005

HSTAA 498D Fall 2004

Bibliography

Berner, Richard C. Seattle Transformed, World War II to Cold War. Charles Press, 1999.

Daniels, Roger. Concentration Camps U.S.A. , Japanese-American and World War II.

Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc., 1972

Droker, Howard Alan. The Seattle Civic Unity Committee and the Civil Rights Movement 1944-1964. Ph.D. diss., University ofWashington , 1974

Dye, Douglas Mark. The Soul of the City: the Work of the SeattleCouncil of Churches during World War Two. Ph.D. diss.,Washington State University , 1997.

Magden, Ronald E. Furusato Tacoma-Pierce County Japanese 1888-1988. Tacoma , Wash. : R-4 Printing, Inc., 1998

Hosokawa, Bill. JACL in Quest of Justice. New York : William Morrow and Company, Inc., 1982.

Takami, David. Executive Order 9066: Fifty Years Before and Fifty Years After. Wing Luke Asian Museum , 1992

1 Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps U.S.A. , (1972), 157

2 Howard Droker. The Seattle Civic Unity Committee and the Civil Rights Movement 1944-64 ( Ph.D. diss. University of Washington 1974) 48

3 Richard C. Berner, _Seattle Transformed: World War II to the Cold War (_1999), 126

4 Bill Hosokawa, JACL In Quest for Justice, , (1982), 24

5 Evidence of Disloyalty of American-Born Japanese, UW Pamphlet file 979.5

6 Magden, Ronald E., _Furusato: Tacoma-Pierce County Japanese 1888-1988 (_1998), 161-163

7 Ibid. 163

8 Stub Nelson, “Anti-Jap Move By Farmers Gains Force”, SeattlePost Intelligencer, 10/7/1944

9 Evidence of Disloyalty of American-Born Japanese, UW Pamphlet file 979.5

10 Remember Pearl Harbor League, Notes from meeting, 4/27/1945, UW Pamphlet file 979.5

11 “Ku-Kluxism on the West Coast,” Collier’s, , 7/14/1945; “Anti-Jap Fee-Seeking Groups Like Hitler, Says Dillon Myer,” Seattle Times, 4/23/1945

12 Douglas Mark Dye, The Soul of the City, The Work of the SeattleCouncil of Churches During WWII, (1997)

13 Droker. The Seattle Civic Unity Committee

14 Dye, Soul of the City, 133

15 Magden, Furusato, 166

16 Berner. Seattle Transformed, 124

17 Stub Nelson, “Anti-Jap Move By Farmers Gains Force”, SeattlePost Intelligencer, 10/7/1944

18 Ibid.

19 Berner, Seattle Transformed, 124

20 Berner, Seattle Transformed , 280

21 Droker, The Seattle Civic Unity Committee ,. 50

22 “Jap Evacuees’ Return After Jan. 1 Approved,” Seattle Times, 12/18/1944

23 Stuart Whitehouse, “Kent-Auburn District Calls Meet; Others Pleased at Return,” The Seattle Star, , 12/18/1944

24 “More Japanese Returning Here” The Seattle Star, , 9/20/1944

25 “Devin Promises Japs Protection,” The Seattle Star, , 12/18/1944

26 Berner, Seattle Transformed , 127

27 Fred Niendorff, “Wallgren Hits Return of Japs to Coast Now,”Seattle Post Intelligencer, , 1/23/1945

28 “Wallgren Hit On Jap Policy,” Seattle Post intelligencer, 1/24/1945

29 Julie Legg, “One Nation – Indivisible – With Liberty and Justice for All,” University of Washington Daily, 1/24/1945 and “Campus Reacts to Daily Editorial,” 1/25/1945

30 “What Do You Say,” The Seattle Star, , 12/18/1944

31 “The Voice of the People,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, 12/30/1944

32 “The Voice of the People,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, 12/25/1944

33 “The Voice of the People,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, 1/29/1945

34 “The Voice of the People”, Seattle Post Intelligencer, 1/26/1945

35 “8 War Families Face House Problem if Jap Ejects Them,” TheSeattle Star, 1/10/1945

36 “The Voice of the People,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, 12/30/1944

37 “Protest Planned On Nisei Release,” The Seattle Star, 12/18/1944

38 “Dr. Sieg Says Japs Welcome on Campus” and “Jensen Welcomes Return of Japs,” The Seattle Star, 12/18/1944

39 “The Voice of the People,” Seattle Post Intelligencer, , 1/26/1945

40 William C. Speidel Jr., “Japanese,” The Seattle Star, 12/14/1944

41 Reverend U.G. Murphy, The Anti-Japanese Agitation. UW pamphlet file 979.515 M95a

42 Droker, The Seattle Civic Unity Committee.

43 Magden, Furusato, 169