Significant federal legal changes responded to and further opened up the sexual revolution for women. The Food and Drug Administration legalized the birth control pill in 1960, and attitudes on sex, abortion, and family planning were rapidly changing. In 1965, the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case Griswold v. Connecticut ruled that states could not ban contraception for married couples, couching that decision in the language of privacy and opening the door to further extensions of that right, including a right to abortion.[58]

As these measures increased the potential independence of women, feminists viewed abortion as key to liberation. 1969 became a “turning-point year in the national debate over abortion” and it was no different in Washington.[59] As radical feminist groups entered the public sphere, they significantly challenged status-quo beliefs while also recognizing that women’s abilities to control their bodies and express sexual and reproductive freedoms needed to be protected by state law.

While Marxist and socialist philosophy criticized the American system of capitalism and electoral institutions as an obstacle to change, in the late 1960s the political context in Washington provided openings that both liberal and radical feminists exploited. Republican Governor Dan Evans expressed support for moderate women’s rights legislation along with other liberal agendas. “We were in an interesting time in the late 60s and early 1970s,” Governor Dan Evans said in an interview. “There were three big issues that overlapped with one another and they were subject to much of the legislative action that occurred during those time… [people were] beginning to really look seriously at the environment, it was in the second phase of the civil rights movement, and the third was opening opportunity for people,” through which women’s rights legislation fit in.[60]

Referendum 20: The Legalization of Abortion

The campaign for abortion reform has been detailed in a companion article "Washington’s 1970 Abortion Reform Victory: The Referendum 20 Campaign" by Angie Weiss. It was fueled by publicity as women were dying from self-induced, illegal, and botched abortions.[61] Cases such as Rasia Trytiak’s death led to the founding of Washington Citizens for Abortion Reform (WCAR), a group initially led by Dr. Samuel Goldenberg, a Seattle psychologist, who was joined by other health professionals and church representatives who emphasized that reform was a basic health issue.[62] Marilyn Ward, who had previously worked on children’s issues, would become the lobbyist for the bill that led to Referendum 20. Republican Senator Joel Pritchard of Seattle, an early WCAR member, introduced a bill in the 1969 legislative session to repeal the state's abortion ban, explaining that the goal was to end “the double standard where people with money can get abortions and people without can’t.”[63] Governor Evans also expressed his support for “a relaxed approach to abortion laws,” indicating the measure had a good chance of passing.[64]

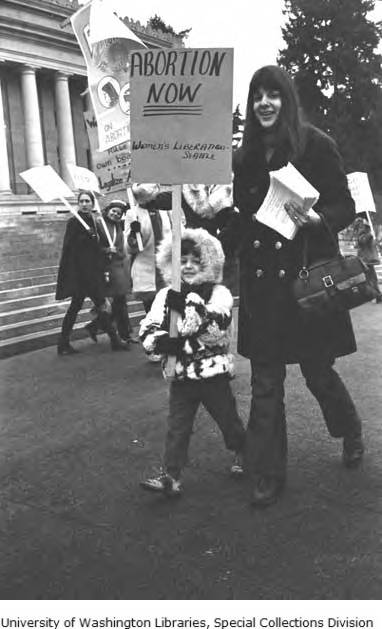

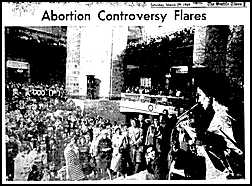

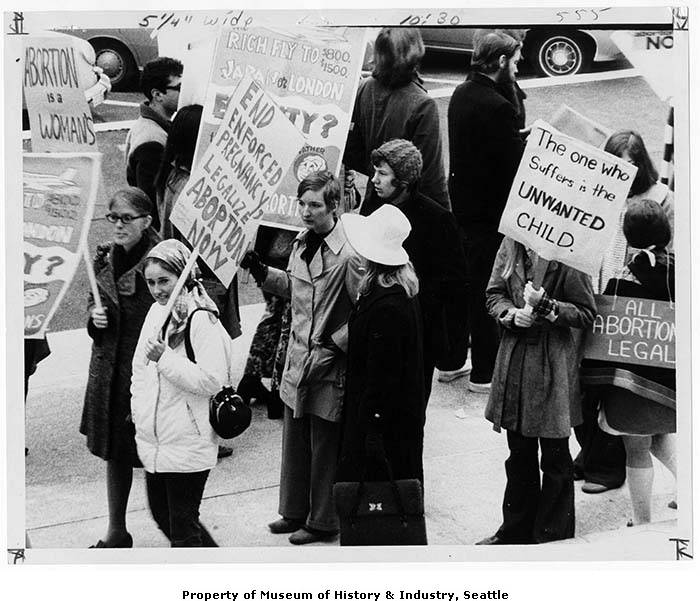

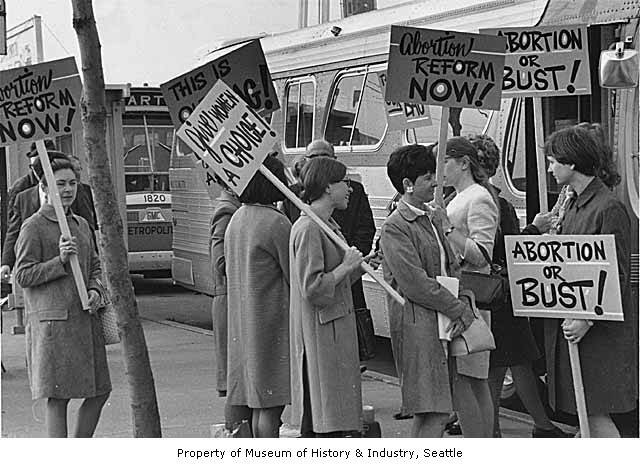

These legislative initiatives initially rested on the efforts of socially liberal moderates like WCAR, Governor Evans, Marilyn Ward, and a bi-partisan group of legislators including almost as many Republicans as Democrats. But the Woman's Liberation movement soon became involved. Clara Fraser of Radical Women heard about the proposed abortion bill while working for welfare clients at the Seattle Opportunities Industrialization Center (SOIC), and said “my personal experience in SOIC has vividly demonstrated to me that excessive and unwanted pregnancies only deepen the poverty cycle for poor women.”[67] Fraser built a coalition of women from Seattle’s Central Area who lobbied in the capitol on March 12, 1969. The women demonstrated to attempt to get the bill out of the Senate Rules Committee, where 17 male senators had blocked the measure, citing religious reasons. They lobbied for abortion “on demand,” viewing abortion as a service that should be readily and equally available to the poor and working class. When Senator William Day accused the bill of implementing “wide open abortion,” feminists responded “That’s what we want.”[68] The very presence of women — and women of color — shocked the overwhelmingly white male Senate. In an interview, Barbara Winslow recalled the demonstration: “We confronted them—can you imagine these people being confronted by confident, aggressive, overwhelmingly African-American women who weren’t gonna take shit from them—they were terrified! It made the front pages of both the Times and the PI, and it took abortion off the back pages.”[69]

The legislators who had sponsored WCAR’s abortion proposal did not welcome the intervention of the radical women's groups, worried that the feminists’ amplification of the issue would jeopardize its chances of passage. When attending the Senate’s public hearing, feminists were strategically kept out of public view by Ward, who wanted to avoid political controversy. Radical feminist protestors threatened this, and Ward said: “We wouldn’t let people like NOW or Radical Women testify in favor of the bill… We said look, we want this to pass; we’re dealing with very conservative middle aged men.”[70] Barbara Winslow of Women’s Liberation-Seattle criticized the WCAR lobbyists, and wrote “The lack of concern by our elected officials was expected—the disgusting hypocrisy by the proponents was not.”[71]

The 1969 encounter was the first experience with the state legislature for many women, and made them aware of how sexist it was. At another march on March 28, organized by Abortion Action Now, Fraser and Radical Women joined over 1,000 women who forced their way into the state Senate carrying signs with messages such as “End Male Chauvinism” and “If a Mother Can’t Decide, Who Can?”[72] When they first arrived at the chambers, they clashed with the Senate Sergeant of Arms who refused them entry until Attorney General Slade Gorton let them in. When they did, the visual was striking: women filled every inch of the Senate corridors, and the difference between protestors and legislators was noticeable. Joel Pritchard, the male Senator who sponsored the bill, said “If these legislators were women instead of men, the bill would be passed without a question.”[73] When Senator Day said that “women are of varying intelligence,” one woman shouted back: “So are legislators!”[74]

Despite the intense lobbying in the Spring of 1969, neither house of the legislature passed the abortion reform bill. Keeping up the pressure, WCAR and its friends in the legislature persuaded Governor Evans to call a special session of the legislature to try again in early 1970. In a tortured serious of compromises, the legislature eventually agreed to Referendum 20. The original bill would have repealed the state's abortion laws outright, thus making abortion legal without restrictions. Opponents first forced significant restrictions, among them married women would need their husband's approval and abortions would be legal only in the first four months. Then in a final compromise, the legislature refused to take responsibility for the (still) pathbreaking law, agreeing instead to send the decision to the voters as a referendum on the November ballot.[75]

Proponents across the spectrum, from WCAR to the radical feminists, were troubled by the compromises but realized that Referendum 20 represented an historic opportunity. Abortion remained outlawed in virtually every state and if the movement could secure reform through a vote of the people, it would be a more powerful victory than an action by the state legislature.[76]

Radical feminists thus had to prove and build popular support for Referendum 20 throughout the state. Their campaign, as opposed to WCAR’s, involved the continued use of grassroots activism and protests as was their style. They advertised how far-reaching and liberalizing abortion reform would be, finding that one in four women in the state had an abortion at some point in her life.[78] Demands for equitable reproductive services also reached others, such as Dr. Frans Koome, a physician who admitted to providing illegal abortions to women in Renton and South King County, a disproportionately minority and poverty-stricken area. Koome became a lightning-rod figure in the media but lined up well with radical’s advertising of abortion as a positive healthcare right.[79] On February 12, 1970, Women’s Liberation-Seattle issued a release supporting the referendum, stating “This will be the most liberal abortion law in the United States, with the exception of Hawaii, and it is a significant step toward a woman’s right to self-determination.”[80]

From legislation to referendum

Despite calls for radical and equitable reform, radicals at times naively ignored the intersectionality of race and gender. The multiracial coalition of women lobbying alongside Radical Women pointed to greater inequalities, as they were said to “express the feelings of most minority women, i.e., that they were sick and tired of their endless mutilation and butchery at the hands of quack abortionists and knitting needles while rich women went to Japan.”[81] This awareness of disproportionality linked to the issue of forced sterilization on Black, Chicana, and Native American women, who made up significant populations in the state. Fannie Lou Hamer, a famous civil rights activist, spoke in Seattle in early 1969 and connected abortion reform to her personal experience with forced sterilization, one that many of the white women in the party and audience were completely unaware of.[82]

But there were others in the Black community who opposed abortion reform and the nascent women's movement. In particular, the emergence of the black nationalist movement led many Black men to vocally speak out against abortion and the use of contraceptives as “genocide”, and some Black women felt they had to put the liberation of Black males first, putting race above gender.[83] Joan Houston, a student at the University of Washington, was quoted in the UW Daily: “The black man needs to have the dominant position at this time. We black women want to be on a pedestal for a while.”

This is not to say that calls for liberation did not appeal to women of color, and the liberation movement sparked the formation of minority women’s groups across universities. Groups such as the Third World Women’s Coalition at the University of Washington emerged as safe spaces for women of color to congregate while also recognizing that their experiences were not fully included in either race-based movements or the women's movement. On the founding of the coalition in 1971, Chicana Chairwoman Leonor Barrientes declared “We are a new organizing force of women representing the ethnic blood lines of Chicano, Asian, Indian and black women. We are about liberation.”[85] Women in the coalitions did not see gender and race as hierarchical discriminations but instead operating alongside each other.

When Referendum 20 passed in November 1970, the Central Area, a majority-minority neighborhood, was one of few Seattle areas that did not vote overwhelmingly in support of abortion’s legalization.[86] However, the achievement was still significant, and Referendum 20 won by 56.49% of statewide votes.[87] These results made Washington one of four states in the country to legalize abortion before Roe v. Wade legalized federal abortion, and could not have been achieved without women’s liberation activists.

“Women Tired of Studies, They Want Action—NOW”[90]

As the women’s liberation movement had an early impact in Washington, nationally liberal and moderate feminists focused on addressing the lack of implementation and enforcement of equal rights legislation. In addition to the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Congress passed Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which created the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), an arm of the government that quickly ignored women’s attempts to use the commission to address incidents of sex-based discrimination. The frustrations over the new law provided some of the impetus behind the lauch of the National Organization for Women (NOW) in 1966.[91] NOW developed effective lobbying tactics, winning media attention and forcing politicians to address women’s rights, and, when this was not successful, encouraging women to work their way into positions of political influence themselves.

Chapters of NOW formed across the country and followed a hierarchical structure. In a 1970 guide to local chapters, leader Shirley Bernard described “NOW is what we’re all about. Improving the status of women NOW. Working peacefully within the system, through the courts, [and] through all of the many Constitutional means available to us.”[92] NOW thus emerged as a group that differentiated itself from women’s liberationists and sought to reform the legal and political status of women through state and national political structures nationwide.

On May 8, 1970, thirteen women met in the chambers of Justice of the Peace Evangeline Starr and chartered the Seattle-King County chapter of NOW, the 36th such group nationwide. Starr was the first official member and formed the Seattle chapter following her membership in the national organization. She herself was a pioneering attorney, one of two women to pass the bar in her 1922 law school class, and a rare example of female political leadership.[93] The first president of Seattle-King County NOW, Zelda K. Boulanger, was a friend of Starr’s. NOW also built on the resources of the Governor’s Commission and recruited attorneys and women in government for membership. This focus on elite women followed the practice of professional women’s groups, including the Business and Professional Women’s Club and the League of Women Voters, but NOW was different in that it focused exclusively on women’s rights.

The group’s tactics in Washington relied both on the national organization and lobbying political actors in the state. NOW leaders met with Governor Evans and asked the governor to make a “commitment for Washington State to [make] basic changes to bring an end to sex discrimination” and to establish an Office of Women’s Rights and Responsibilities [94] In response, Evans formed the Interagency Committee on the Status of Women (ICSW), a group that extended the work of the original Committee on the Status of Women and included members from across state government agencies, including Assistant Attorney General Gayle Berry and Maryan Reynolds from the State Library, who had been secretary for the commission.[95] This was a significant effort that coalesced state resources in multiple areas towards women, with the goal not only to review the status of women’s legislation but also to make recommendations for upcoming action and legislative sessions.[96]

A few months after the first meeting of NOW, Governor Evans, along with Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman, celebrated “Women’s Day” on August 26, 1970, fifty years after the passage of the 19th Amendment and in support of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment. Coinciding with a nationwide Women’s Strike for Equality, the event brought together feminists of all varieties, including NOW, Radical Women, WL-S, and the newly formed University of Washington Women’s Commission marching in Seattle streets, distributing leaflets, and focusing on recruiting more women into their ranks. Their goal, as stated by Dr. Judith Shapiro of WL-S, was to “reach women who hadn’t been involved before… [and] convince them that women’s liberation is for every woman.”[97]

At the same time, feminists were not taken seriously by the media, which ridiculed the event and women’s groups for challenging gender norms. The Seattle Post-Intelligencer ran a “Ladies Day” editorial on Women’s Day, attacking the “more militant members of the so-called weaker sex” and questioning the need for a movement at all, stating “the ladies should be put on notice that they can’t have it both ways." The article then warned, "If they persist in their folly, there is bound to be a male backlash. Men will begin to rebel at paying the bills, taking out the garbage, zipping the backs of dresses… and permitting women to abandon sinking ships ahead of them.”[98] Similarly patronizing rhetoric appeared in other articles such as one titled “Just Stay Exciting, Pretty” that appeared in the PI in December 1970. The male author instructed women to stay away from politics and dismissed their interests in issues such as abortion and the ERA as “highly emotional.”[99] Radicals, especially, were described as irate, angry, and not to be taken seriously.

Concern over public perceptions exacerbated tensions within the movement. NOW wanted to avoid the label of “liberation” arguing it invited the stereotype “militant feminist.” At times, liberal feminists and NOW members deliberately avoided being associated with radical liberation groups and considered themselves more like a civil rights style organization, embracing the comparison to the “NAACP of women’s liberation.”[100] They believed, as radical feminists did not, that women could achieve equality through the existing sociopolitical institutions and that this did not necessitate a rethinking of gender and relationships. In fact, on its founding they advertised the group for both men and women, stating “contrary to what some women believe, there are many men who are interested,”[101] and “Just as the NAACP welcomes whites in its membership, the National Organization for Women welcomes male members.”[102] They did not want to be seen as advocating for complete societal revolution or radical social change.

This approach extended to their tactics. Correspondence in the NOW-Seattle chapter records preserved in the UW Special Collections library show that some leaders urged member to style themselves as a “well dressed, quiet in decorum” alternative to women’s liberation groups who, in their opinion, didn’t “do anything but give them fuel for their fire.”[103] Overall, liberal and radical feminists did not meet eye to eye in terms of conceptualizing how both genders could work and live together.

While these differences led liberal and radical feminists to clearly differentiate from each other, members of NOW did not disdain radical women completely and recognized their common ground. As chapter President Boulanger wrote, “NOW hopes to establish a favorable image which will be a credit to the many congenial people of integrity who make up the ranks of the women’s liberation movement.”[104] The sexual revolution helped to bring this realization along, as secretary Connie Hansen realized that “as is apparent in our young people, individuals no longer count their value in how well their appearance coincides with the stereotype of a sexual object.”[105] They respected the young women who made up women’s liberation for resisting the same patriarchal and sexist attitudes they had been pinned into for most of their lives.

Legislation

The issues NOW and the Interagency Committee took on represented their intent to focus on the implementation of women’s legislation, and these were largely wrapped up in the concepts of equal pay and equal rights for women. One early success was HB 594, a 1971 measure that added sex as a category to state antidiscrimination employment laws. Sponsored by Rep. Lois North and brought forth by ICSW, the measure sought to reinforce and implement the state Equal Pay Act of 1943 as well as Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.[106] Governor Evans signed the bill on May 17, 1971, establishing for the first time a mechanism for women to report complaints on the basis of sex discrimination through the state’s Human Rights Commission.[107] The law showed how Washington was willing to strengthen and implement women’s legislation in absence of federal action.

Other bills included legislation to allow wives to sue alone for personal injury and allowing women to choose to keep her maiden name if she got married. These initial measures continued to portray women’s rights legislation as minor and necessary reforms, not drastic change, an approach that was appealing to state legislators. “I have been impressed with the practical approach taken by your organization… I stand ready to support this approach in other areas when reasonable legislation is requested,” Representative Arthur C. Brown wrote to NOW president Helen Sommers.[108] NOW became a powerful and reliable advocate for women’s legislation, and built strong and favorable relationships with legislators.

Chief among concerns for NOW was passage and ratification of the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Passed by the US Congress on March 22, 1972, the amendment was sent to Washington State, where supporters deliberately turned to two avenues of ratification, seeking to pass the ERA both as an amendment to the US Constitution and to the Washington State Constitution as well. The state amendment, which stated “Equality of rights and responsibility under the law shall not be denied or abridged on account of sex,” was proposed as a bill to both chambers of the legislature as House Joint Resolution 61 and Senate Joint Resolution 106.[109] This was accomplished and passed in both largely due to the work of Rep. North, the prime sponsor of HJR 61, who lobbied her male colleagues to vote for it. Instead of merely adopting the ERA to the state’s constitution without public input, the legislature sent HJR 61 to voters as a ballot measure in the November 1972 election, just as the referendum measure had secured the legalization of abortion. This further differentiated Washington from other states and reinforced its distinctive political structure.

In an interview with the author, Governor Evans spoke of his motivations to support the amendment and its effects. “In those days there was clearly quite open discrimination against women when they’re in competition with men for any kind of job,” Evans said. [It] “doesn’t have to be in every phase of life having an equal number of men and women doing things. It means that there is [equal] opportunity.”[110] The ERA therefore fit into broader efforts to address legal discrimination in the state and spoke to the governor’s efforts to use legislation to transform the social environment and opportunities available for women.

NOW’s first efforts to pass the ERA focused on pressuring Governor Evans to create the Washington State Women’s Council on October 21, 1971, an organization that developed women’s lobbying into an arm of the governor’s office. The 15-member council was chaired by Anne Winchester, former dean of women at Washington State University, and executive director Gisela Taber. Two males also sat on the council, including Sen. Joel Pritchard, the initial sponsor of the abortion bill.[111] Other organizations, such as the Seattle Women’s Commission, founded in April 1971, and the Associated Students of the University of Washington Women’s Commission, represented the growth of institutional women’s groups from grassroots liberation organizations and became central to the ERA campaign as well.[112]

“Woman's Week"

The Women’s Council also reflected NOW’s lobbying for more diverse women in the movement, writing in a press release that “Although the feminist movement may be composed predominately of 'middle-class, professional women', their efforts are directed strongly toward the area of greatest need-- that of the low-income, working woman.”[113] When NOW first began operating in 1971 and 1972, they focused on cases and individual complaints of employment discrimination as a solution to addressing economic inequality. In addition to resolving individual cases, NOW also lobbied for the appointment of minority and low-income women to the Governor's Women's Council and the Human Rights Commission. In a letter to Governor Evans, president Elaine Latourell explained NOW's view that “women living on low, fixed incomes regardless of race, creed or age are indeed a minority.”[114] While Latourell acknowledged the need for a diversity of perspective within the women’s movement, NOW was also blind to race at times. Sue Tomita said “I feel I have been appointed because I am an Asian, so two things are on my mind: racism and sexism.”[115]

Governor Evans organized another Woman’s Week in the summer of 1972 to rally for the ERA. By this time, the governor’s endorsement as well as networking efforts by NOW led to a number of organizations in support of the ERA, including the League of Women Voters, the Washington Women’s Political Caucus, Washington Women Lawyers, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), as well as government organizations including the ERA Campaign Committee. The efforts of NOW and other liberal feminists to garner support for the state ERA, which was on the November 1972 ballot as House Joint Resolution 61 (HJR 61), were impressive and reflected the height of women’s ability to organize.[116]

The council focused exclusively on two measures for the 1972 session: the ERA and a community property bill granting women equal ownership to property in marriage. The Women’s Council was the most significant arm of women’s lobbying, but they also took on a narrow focus by focusing on the two main reforms, seeing their role as to support “only that legislation which confers equal rights.”[117] By 1972, in a pamphlet titled “The Woman Lobbyist,” Joy Belle Conrad-Rice declared

Women’s rights legislation is in style now … In 1965, there were six bills for women introduced; in 1967 four, 1969 six, and 1971 twenty-four. In 1971 the total number of bills introduced in the Senate was 923 and in the House 1129! It is an uphill battle, but the 1972 women’s rights bills could pass with the help of the woman lobbyist.[118]

The bills Rice was referring to included those of priority to NOW in the 1972 legislative session.

Winning the ERA

The legislature’s focus directly excluded protective labor legislation such as limitations on the number of days and hours women could work, provisions opposed because the were seen as limiting women’s economic opportunity and upwards mobility in comparison to men. This exclusion of labor rights, in addition to a proclamation by Washington State Attorney General Slade Gorton that HB 594 had eliminated this legislation already, caused tension with radical feminists who advocated for both worker protections and women’s rights. Both Radical Women and WL-S advocated for the extension of protective labor legislation to all workers, but disagreed over whether the ERA would positively or negatively impact these efforts. RW supported the ERA, as Fraser believed it would give “women a legal basis for court action on all fronts, from fair housing to fair treatment in the media.”[119] However, Women’s Liberation-Seattle opposed it, choosing instead to support the extension of protective legislation to all workers instead of its elimination for women.[120] These disputes, however, did not significantly affect the discussion as NOW had taken over the mainstream political momentum of the movement. By the time of the 1972 election, the ERA dominated women’s rights lobbying efforts and all feminists, including WL-S, came together to support it.

A key tactic of liberal feminists involved recruiting women for public office and positions of influence. Other tactics included distributing leaflets, organizing letter writing campaigns, and making guides for women to reach out to their elected officials. All of these efforts encouraged women to make government work for them and to be interested in civic engagement, turning a system that did not work for them into one that did. After formation of the Women’s Council, feminists focused on getting the ERA through the legislature, over 200 of them appearing in Olympia early 1972. The political strength of women was rapidly growing: “The main push by NOW and the democratic women was a sort of double whammy. First one asks the gentleman—politely—to support the amendment… then one reminds the gentleman that if he doesn’t vote for it, he may well be voted out of office.”[121] Both radical and liberal feminists took part in these efforts, recognizing the need to educate state legislators about sex discrimination and appear as a united force.

Efforts to ratify the ERA also brought together women across the state for a common cause and further shaped its social environment. By 1972, 13 chapters of NOW had formed across the state, helping to mobilize women in electorally significant areas.[122] Newsletters, referred to as “Nowsletters,” cropped up from county to county, passing information, legislative updates and dates of meetings to women in Kitsap County, Snohomish and Tacoma as well as the cities of Spokane, Highline, and Bellevue-Eastside to name a few.[123] These groups adopted tactics of the liberation movement, hosting consciousness-raising meetings and educational sessions, while merging this with doorbelling for the ERA and obtaining financial and political support.

As liberals and radicals capitalized on political momentum and lobbied together for the ERA, political differences soon emerged. In October 1972, national feminist activist Gloria Steinem visited Seattle along with Black feminist activist Margaret Sloan to demonstrate how the movement was inviting of African Americans and minorities. The event energized many feminists while also introducing criticisms from radicals who challenged whether the ERA and the middle-class liberal feminist movement at large was inclusive of all women.[124]

All of the collaborative efforts among feminists to lobby for the ERA headed towards the November 1972 election which would decide whether the state adopted its own equal rights law. Results for HJR 61 came in late, and the issue turned into an unexpectedly controversial one, with results not coming in on election day. Ultimately though, it was worth the wait: the ERA passed by a tiny margin of 3,369 votes, carried by voters in King County. The successful election result meant that Washingto adopted the Equal Rights Amendment as the 61st amendment to the state constitution on January 9, 1973.[125]

The next step was ratifying the federal ERA. Despite the recent vote, opponents hoped to block ratification in the state Senate when the legislature met at the start of 1973. Contentious debate from vocal opponents meant supporters had to resume lobbying for the ERA at legislative hearings, leading some feminists to question whether the bill was still alive or not. But the popular support and the organization by NOW proved victorious, and the state ratified the federal ERA on March 22, 1973, one year after its introduction in the U.S. Congress. An April edition of Pandora reported that the “Senate Relents, Ratifies ERA.”[126]

Radical state changes

The passage of HJR 61 was truly a landmark moment for women’s legal rights in the state, prompting an evaluation of all laws in the state discriminating on the basis of sex and eliminating barriers that had long been in place against women. The Senate quickly passed an ERA implementation bill to “make the necessary changes in all existing non-controversial laws to bring them in line with HJR 61.” This included the elimination of over 130 laws that discriminated on the basis of sex, opening up more opportunities for women. The passage of the state and federal amendments, paired with legislative action for its implementation, further made the state a national leader on women’s equality, as the federal ERA still did not have enough state votes for ratification.

Not only did the mobilization of women in politics lead to the success on the ballot, but 1972 also became a turning point for many women entering the state legislature. Out of 26 women who ran in 1972, 12 won election to the House of Representatives, nearly doubling the number of women in the body and halting “a nearly two-decade decline.”[127] This included Representative Peggy Joan Maxie, the first Black female to win an election to the state House of Representatives and Helen Sommers, the former president of Seattle- King County NOW.[128] In 1973, Maxie, along with Rosalind Woodhouse, the African-American president of the Seattle Women’s Commission, formed Women in Unity, a political group that saw itself as a “version” of the League for Women Voters that encouraged black women to run for political office.[129] Many of the women elected in 1972 and in the decade ahead went on to have long and successful careers influencing the legislature and mentoring next generations of women, and were crucial to combating its institutional structure and advocating for women’s rights legislation.

Women continued to build on political momentum the next year, as legislators and legal activists worked to pass reforms that signaled transformative social change. Most notable was the passage of the no-fault divorce law in 1973, a measure sponsored by Rep. Maxie that eliminated barriers to getting a divorce to an “irretrievable breakdown” in the marriage and the removal of blame from either party.[130] By 1975, the Seattle Times noted that more than half of the state’s marriages ended in divorce, largely a pent-up issue released by passage of the law.[131]

This “radical state change” points to how the calls and tactics of the movement- consciousness-raising sessions, political organizing, and forming bonds with other women- drastically altered women’s perceptions of themselves and led them to seek better relationships along with social and economic independence.[132] The ability to file for divorce largely represented a negative right granting women the freedom to leave their marriages, such as Dotty DeCoster, an activist who said “I actually waited until this passed to get a divorce.”[133] The empowerment of women to sue independently was another reform of the movement, allowing lesbian mothers to obtain child custody, and women to sue for personal injury and ownership of community property.[134] Even simple legislation allowing women to choose whether or not she took her husband’s surname affected the sense that attitudes towards women’s roles were changing.[135]

“Coordination Was Badly Needed Among Feminists”[136]

The ERA campaign had exposed greater concerns over the inability of moderate and radical feminist groups to work together. These were attempted to be addressed with the forming of the Feminist Coordinating Council (FCC) in 1972, a conglomeration of feminist groups “both political in orientation and apolitical, representing a cross section of the women’s movement in Washington.”[137] Members of the FCC included Leftist groups such as the Freedom Socialist Party, Seattle Women Act for Peace, Radical Women, social groups including the Gay Women’s Alliance, and more liberal groups such as NOW, the Seattle Women’s Commission, and Washington Women Lawyers. Organizer Lynn Bruner attempted to bring these groups together, stating “We who consider ourselves feminists are a diverse group, having varied political and ideological commitments. There will be issues upon which we can all agree, and where we cannot we can, nonetheless, profit from debate and the free exchange of ideas and information.”[138] The council held ERA benefits and participated in rallies and events, signaling a unified feminist movement.

In 1973 the FCC quickly erupted into controversy over the political differences between liberal and radical feminists, and seven women’s organizations resigned, accusing members of Radical Women of using the organization for their own gains. This perhaps represented a greater argument over the issues of political control and not the act of political lobbying itself, something that NOW was very familiar with. Radical Women lashed out at Pandora as well, accusing it of not supporting the tenets of radical feminism. This marked an end to the few years of collaboration. By October, Pandora reported that the FCC had “lost much credibility with the public as well as among feminists.”[139]

The failure to provide a unified front thus jeopardized efforts to secure additional protections, including protections against sexual harassment and rape that both wings of the movement wanted, and a rethinking of prostitution laws that was a point of disagreement. One notable effort started with the FCC’s drafting of an ordinance for a Special Protection Unit in the Seattle Police Department and the creation of a Commission on Crimes of Violence Against Women, infuriated by an officer who was accused of rape and allowed to return back to the force. NOW lobbied Mayor Uhlman to remove the officer and the Women’s Council also endorsed the Special Protection ordinance, which would establish funding for a police team to respond to rape and domestic violence calls.[140]

Seattle City Councilmember Jeanette Williams brought the issue to a hearing on May 11, 1975 but failed to persuade the City Council to adopt the Ordinance. Under pressure by women's groups the legislature in 1975 passed an overhaul of the state’s rape laws. But the reforms were incomplete. The new law left “rape myths and gender stereotypes” embedded in courtroom practices, once again highlighting the difference between legislation and implementation.[142]

Conservative backlash

While feminists fought for the expansion of rights, conservative women and the onset of antiabortion and anti-ERA movements eroded the feminist movement nationwide. While Washington had ratified the federal ERA in 1973, by 1979, the amendment’s initial deadline, the ERA had not achieved the 38 state threshold required for an amendment to the US Constitution. This was largely due to the leadership of Phyllis Schlafly, who organized a counter movement of conservative women against ‘women’s libbers’ and formed the organizations STOP ERA and Eagle Forum, building conservative women’s political caucuses that mimicked the ones feminists had formed.

Political and institutional support that had supported the feminist movement’s rapid success in Washington was also fading. Schlafly’s leadership and the development of opposition to feminist organizations encouraged similar groups in Washington, such as the Voice for the Unborn and Happiness for Motherhood Eternal (HOME), antifeminist campaigns and organizations active during the campaigns to legalize abortion and ratify the ERA. While these groups were not as politically effective as the women’s movement in the state, they began to change the momentum and media focus as TV and major newspapers turned to stories about the backlash against feminism. Finally, after ratification of the ERA and passage of no-fault divorce reform in 1973, signs seemed to hint, according to Representative Karen Fraser, that women’s rights was “no longer a significant political matter” in the state and that this sense was “even beginning to pervade the Governor’s staff.”[146]

At the same time, feminist establishments and institutions that both radicals and liberal feminists worked so hard to build dissolved quickly. By 1974, merely a year after the passage of the ERA, the state Women’s Council was in trouble. Feminists had introduced a bill to grant the council statutory authorization, which would make it a permanent part of the executive’s office.[147] However, while its members perceived funding of the Council as a reasonable next step, antigovernment and religious conservatives latched onto the measure as an issue of public contention, placing the Council on the defensive and preventing their ability to introduce further legislation.[148] The measure to fund the council was introduced in 1975 and was struck down, leading VanBronkhurst to conclude that the movement had shifted to an environment of “apathy” focused on “continuation of gains already made for women.”[149]

More shifts were in motion; in 1977, Governor Dixy Lee Ray replaced Governor Evans. The state’s first female governor but also a political outsider, Ray did not have the political will or support to stop the Women’s Council from falling prey to a referendum campaign in late 1977, where it was thus shot down in the 1977 election. All of these tensions culminated in the 1977 Women’s Year Conference in Ellensburg, where efforts to organize in support of the federal ERA were overrun by conservative opponents who ran against the women’s planks. The demise of the Women’s Council and the events of the Women’s Year Conference symbolized the end of the movement’s grasp on Washington state politics and a shift towards a more conservative tilt. Additionally, as Janine Parry argues, the use of a ballot measure to defund the Women’s Council pointed to how the “long history of progressive gender politics collided with its equally enduring libertarian and conservative streaks.”[150] The state’s participatory democracy structure both empowered the fast ascendancy of women’s groups and legislation while also leaving them fragile and vulnerable.

The movement, perhaps overly ambitious, left several unfulfilled promises. Fifty years later, women are still struggling to vindicate sexual harassment complaints in the workplace and to seek higher political office. The onslaught of conservative backlash and the incorporation of antifeminism into a core tenet of the Republican party left only the most concrete freedoms and negative rights of the women’s movement intact. The feminist establishment that women worked so hard to build- all of the commissions and councils that brought women closer to government and positions of influence-- were largely eliminated. Most notably, the 2022 Supreme Court decision against Roe v. Wade may make positive rights completely irrelevant, threatening to eliminate the line between privacy, freedom, and autonomy for women across the country and endangering the legacy of the movement. Reflecting on the movement’s legacy today, Winslow said “None of us anticipated the misogynist assault – when we won abortion, we figured our struggles would just be to expand reproductive health. We didn’t realize that we would be fighting just to save the little that we got.”[151] In many ways, the goals the feminist movement set are still those that women have continued to seek since 1970.

As national politics have wavered in favor of and against women’s rights, the legacy of the second-wave movement in Washington leaves several concrete advancements in place and points to the state’s unique accomplishments. The comprehensive scope and number of legislative reforms, achieved in such a short period of time between 1970 and 1977, was truly one of the movement’s greatest victories, opening reproductive and economic freedoms for women and unlocking many of the rights women in the state take for granted today. The dialogue between what was most fundamental to women’s lives and equity was fully fledged in Washington between liberal and radical feminists, who, despite their disagreements, both profoundly impacted the social and political contexts they were living in. The ability for a bipartisan coalition of Republicans and Democrats, men and women, liberal and radical feminists to rally in support of abortion reform, the ERA, and radical social change was a remarkable achievement, displaying a kind of political unity that cannot be imagined today. The leadership of Governor Dan Evans lent powerful support and leadership to the passage of women’s legislation, defining gender equality as an issue beyond party and taking on the complexities of implementing legal changes for women when the federal government fell behind. All of these changes affected the political environment and made the state’s advancement of impactful reforms for women truly exceptional. In terms of “what rights people should have, I think that we’re ahead of most of the country in that respect,” Governor Evans said. “I think that women have succeeded, they’ve had to fight for everything, but they’ve succeeded in having to open up opportunities [and] we have a lot more equality in the workforce than we did then.”[152]

Finally, one of the movement’s most long-lasting legacies is the entry of women into public office and positions of influence. From a time when there were no women in the state’s top executive offices, Washington has had two female governors and women currently serve in many positions of higher office, making up majorities in the courts, legislative parties, state agencies and government. Women are taken seriously in professional roles and have the freedom of choice to direct decisions about their bodies and lives, and the status of women today is more representative of a diverse citizenry responsive to race, sexuality, gender and class differences. By questioning their role in the family, workplaces, political institutions, and social movements, Washington’s feminist activists laid the groundwork for generations of women to experience more social, political, economic, and legal freedoms than they had a mere decade earlier, introducing a lasting revolution.

Honors thesis, UW History Department March 2022

winner of the 2022 Library Research Award from University of Washington Libraries

[58] Self, All in the Family, 147.

[59] Self, 145.

[60] Governor Daniel Evans, interview with author, September 13 2021.

[61] James Gregory, “When Abortion Was Illegal (and Deadly): Seattle’s Maternal Death Toll,” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. Accessed March 01, 2022,

[62] Angie Weiss, “Washington’s 1970 Abortion Reform Victory: The Referendum 20 Campaign," Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project." Cassandra Tate, “Abortion Reform in Washington State,” HistoryLink.org, February 26, 2003.

[63] “Abortion Bill May Come Before Legislature Today” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, January 24, 1969, p. 17

[64] “No ’69 Tax Hike, Says Evans” Tacoma News Tribune, January 14, 1969.

[65] Sally Raleigh, “Dear Mr. Legislator,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 2, 1969, p. 87

[67] “50 Women Demand Abortion-Bill Action” Seattle Times, March 13, 1969, p. 8

[68] Scates, Women Demand Senate Action on Abortion Bill”

[69] Winslow, interview with author, Jan 28, 2022.

[70] “Marilyn Ward recalls the campaign to reform Washington’s abortion law.” Historylink.org

[71] Women’s Liberation-Seattle publication, 1970, 2272, Box 17 Folder 29 Activism, Jody Aliesan Papers, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[72] Don Hannula,“Marchers Failed to Move Abortion Bill” Seattle Times, March 29, 1969, p. 17

[73] Sally Raleigh, “Dear Mr. Legislator” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, March 2, 1969, p. 87

[74] 50 women demand Abortion-Bill Action

[75] Weiss, “Washington's 1970 Abortion Reform Victory."

[76] Weiss, “Washington's 1970 Abortion Reform Victory."

[77] Parry, Janine A. “Putting Feminism to a Vote: The Washington State Women’s Council, 1963-78.” The Pacific Northwest Quarterly 91, no. 4 (2000), 172.

[78] Women’s Liberation-Seattle publication, Jody Aliesan papers.

[79] Schwartz, Susan, “400 Pack Meeting Room to Hear Koome” Seattle Times, January 18, 1970, p. 23

[80] Women’s Liberation-Seattle publication, Jody Aliesan papers.

[81] Susan Bondurat, “Referendum 20: A Radical Critique” Pandora 3, November 16, 1970, p. 4

[82] Winslow, “Primary and Secondary Contradictions in Seattle,” 243.

[83] Patricia Robinson, Lilith, September 1, 1968.

[84] Special Women’s edition of UW Daily, December 3, 1970, 2272-001, Box 17 Folder 40 Newspapers, Jody Aliesan papers, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[85] “Third World Women fight triple oppression,” Daily of the University of Washington, May 21, 1971, p. 19

[86] Barbara Winslow, Interview by Jessie Kindig and Trevor Griffey, Antiwar and Radical History Project, March 25, 2009.

[87] “Elections Search Results: November 1970 General” Elections, Washington Secretary of State, accessed on March 15, 2022, https://www.sos.wa.gov/elections/results_report.aspx?e=42&c=&c2=&t=&t2=&p=&p2=20&y=1970

[88] Weiss, “Washington’s 1970 Abortion Reform Victory.”

[89] Ibid.

[90] Shelby Gilje and Joan Wolverton, “Women Tired of Studies, They Want Action-Now,” Seattle Times, April 24, 1970, p. 27.

[91] Rosen, p. 75

[92] Correspondence from Shirley Bernard to Seattle-King County NOW, 6 May 1970, 6204-001, Box 5 Folder 23 Outgoing Correspondence 1966-1970, Zelda Boulanger papers, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[93] Seattle Times, July 14, 1922, p. 19; Charles E. Brown, “Evangeline Starr: Retired Judge” Seattle Times, January 31, 1990, p. D4

[94] Correspondence from Zelda K. Boulanger to Governor Daniel J. Evans, 24 October 1970, 6204-001, Box 5 Folder 24 Outgoing Correspondence 1970, Zelda K. Boulanger Papers, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[95] Dawn Baker, “ICESW Celebrates 30th Anniversary,” Interagency Committee of State Employed Women, July/August 2000, https://digitalarchives.wa.gov/do/0E6E9567E43F9F173E31B492F6A0A398.pdf

[96] Correspondence from Governor Daniel Evans to Zelda K. Boulanger, 30 October 1970, 2887-001, National Organization for Women Records 1970-2000, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[97] Ruth Pumphrey, “Women’s Day Meetings Set,” Seattle PI, August 28, 1970, p. 17

[98] “Ladies Day” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, August 26, 1970, p. 12

[99] Rick Anderson, “Just Stay Exciting, Pretty” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, December 27, 1970

[100] Press Release to the UW Daily, 18 May 1971, Box 2 Folder 23, NOW Seattle-King County 1970-1972, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[101] Edana Daw, “N.O.W.: It’s for Men, Women” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, May 31, 1970, p. 55

[102] Press Release to the UW Daily, NOW Seattle-King County 1970-1972 records.

[103] Correspondence to Elaine Day LaTourell, 2887-002, Box 2 Regional Newsletters, National Organization for Women Seattle-King County Chapter Records 1970-1976, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[104] Correspondence from Zelda K. Boulanger to Edna Daw, 6 June 1970, 6204-001, Box 5, Folder 24 outgoing correspondence 1970, Zelda K. Boulanger papers, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[105] Correspondence from Connie Hansen to The Seattle Times, 2 June 1970, Box 5 Folder 23 Outgoing Correspondence 1966-1970, Zelda K. Boulanger Papers, Special Collections, University of Washington

[106] Sally Gene Mahoney, “Women tell state legislators about sex discrimination” Seattle Times, February 26, 1971, p. 30

[107] State Law Against Discrimination press release, Box 1 Folder 12, NOW Seattle-King County Chapter Records 1970-1976, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[108] Correspondence from Representative Arthur C. Brown to Helen Sommers, 27 January 1972, 2887-001, Box 2 Folder 10, NOW Seattle-King County Records 1970-1972, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[109] Washington Constitution, ARTICLE XXXI, Sec.1, 1972

[110] Governor Evans, interview with author, September 13, 2021.

[111] “State Women’s Council Created,” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Nov 3, 1971, p. 11

[112] Hope Morris, “Equal Rights on the Ballot: The 1972-73 Campaign for Washington State’s ERA,” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium, University of Washington.

[113] Correspondence from Connie Hansen to The Seattle Times, 2 June 1970, Box 5 Folder 23 Outgoing Correspondence 1966-1970, Zelda K. Boulanger Papers, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[114] Correspondence from Elaine Day Latourell to Governor Evans, 19 July 1972, Box 1 Folder 2 Outgoing Correspondence 1972, NOW Seattle-King County Chapter Records, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[115] Sally Gene Mahoney, “New state women’s council—an answer for confusion?” Seattle Times, November 7, 1971, p. 109

[116] Morris, “Equal Rights on the Ballot.”

[117] Sally Gene Mahoney, “Legislation is main topic for state’s women council” Seattle Times, January 19, 1972.

[118] “The Woman Lobbyist,” Box 2 Folder 6, NOW Seattle-King County Chapter Records 1970-1976, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[119] Susan Paynter, “Feminists Coordinate Efforts,” Seattle P-I, October 25, 1972, FCC Historical Features, Bylaws 1972.

[120] Barbara Winslow, Revolutionary Feminists: the Women's Liberation Movement in Seattle 1965-1975, Duke University Press, forthcoming. “WL-S on ERA” And Ain’t I a Woman!, 1 no 4, p. 4 (n.d.)

[121] Erin VanBronkhurst, “ERA Passes Senate” Pandora, February 23, 1973 p. 2

[122] "N.O.W. preparing for its first state meeting" Seattle Times, May 7, 1972

[123] National Organization for Women, Seattle-King County Chapter Records, 1970-2000, Special Collections, Manuscripts and Archives Division, University of Washington Libraries. Seattle, Washington.

[124] Morris, “Equal Rights on the Ballot.”

[125] Mahoney, Sally Gene, "Equal Rights Amendment now officially part of Constitution" Seattle Times, January 10, 1973, p. 29

[126] Susan Brownell, “Senate Relents, Ratifies ERA” Pandora, vol 3 issue 13, April 3, 1973, p. 3

[127] Sally Gene Mahoney, “Women candidates fare well in state contests,” Seattle Times, November 9, 1972, p. 49.

[128] Elected Washington Women. (1983). Political Pioneers : The Women Lawmakers. Elected Washington Women; Mary T. Henry, “Marjorie Edwina Pitter King (1921-1996)” HistoryLink.org, November 2, 2008, https://historylink.org/file/8828; Mahoney, ibid.

[129] Quin’Nita Cobbins, “Black Emeralds: African American Women’s Political Activism in Seattle, 1941-2000,” 196.

[130] Lorrie Temple, “Divorce: Legal Reforms or Semantic Alterations?” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, February 11, 1963, p. 31

[131] Susan Schwartz, “Divorce ends half of marriages here,” Seattle Timesˆ, August 31, 1975, p. 35

[132] Lyle Burt, “No-fault’ divorce effective tomorrow,” Seattle Times, July 15, 1973, p. 18

[133] Dotty DeCoster, interview with Heather MacIntosh, “The Women’s Movement and Radical Politics in Seattle, 1964-1980” HistoryLink.org, April 15, 2000.

[134] “A Small Victory for Lesbian Mothers,” Pandora 3, no. 1, October 17, 1972, p.5

[135] Joy Belle Conrad-Rice, “Woman Not Obligated to Use Husband’s Name,” Pandora 3, no. 16, May 15, 1973, p. 4

[136] Jean Withers, 6 October 1972, 2414-001, Box 1 Folder 1 Historical Features 1972, Feminist Coordinating Council Records, 1971-1977, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[137] Handwritten letter, 2887-002, Box 1, Folder 12, National Organization for Women Seattle-King County Chapter records 1970-1976, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[138] Letter from Lynn Y. Bruner, 19 August 1972, Box 1 Folder 12, NOW Seattle-King County Chapter Records 1970-1976, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[139] “Women’s Commission Sets New Goals” Pandora, September 4, 1973, vol 3 issue 24

[140] Sally Gene Mahoney, “Council hears ‘whys’ of proposed ordinance,” Seattle Times, March 12, 1975, p. 24

[141] Ibid, p. 24

[142] Sara Leonetti, “Rape and the Law: An Examination of the Relationship between Sexist Cultural Attitudes and Washington State’s 1975 Rape Law Revision,” University of Washington, 26 March 2015, 37.

[143] Susan Faludi, Backlash: Undeclared War Against American Women (New York: Anchor Books, 1992).

[144] Self, All in the Family, 38.

[145] Self, 274.

[146] “State Leaders Ignore Women’s Needs” Pandora, September 4, 1973.

[147] Erin VanBronkhurst, “Coalition Formed to Save State Women’s Council” Pandora, January 8, 1974.

[148] Parry, 174.

[149] Erin VanBronkurst, “Women’s Bills Face Apathy,” Pandora, April 1975, p. 3

[150] Parry, 171.

[151] Barbara Winslow, interview with author.

[152] Governor Evans, interview with author, September 13, 2021.