Drinking and fighting, insults and pistols: it may sound like a scene from the Wild West, but these were the circumstances that gave birth to one of Seattle’s civil rights battles in the 1960s, and galvanized a movement for police accountability that continues to this day. What began as fight between two white police officers and two unarmed black men in Seattle’s predominantly non-white Central District immediately became political when an officer shot and killed one of the African Americans. Occurring during the heat of the civil rights movement in 1965, the shooting inspired local African American community leaders to demand justice by making Seattle’s police department more accountable to its citizens. And the unique method of direct action they used to call for justice was the “freedom patrol.”

The freedom patrols—in which community leaders walked behind and observed Seattle’s beat-cops in the Central District— began in July 1965, and were used for over a year even though the campaign expanded to include other methods within the first couple months. At a time when race relations were tense across the nation civil rights groups “policing the police” elicited a great deal of support both for and against the fight to reform police practices. This essay looks at the shooting that precipitated the 1965 campaign to confront police harassment and the most dramatic tactic of that campaign, the freedom patrols, sometimes described as a “walking review board” of police actions reflecting the major demand of the campaign – independent review boards of police practices. Although the freedom patrols made some inroads and brought a lot of media attention to the issue of police accountability in Seattle, this was a campaign that did not end in victory for civil rights activists.

Background

Seattle’s police department and its black residents had a history of contentious relations in the decades before 1965. Seattle’s first African American police officer quit soon after being appointed in 1890.1 In 1938, three Seattle police officers beat an African American to death. Pressure from the NAACP and Urban League undermined the police cover up, but Washington State’s governor pardoned the men in 1939 even though they had been convicted of second degree manslaughter and sentenced to 20 years each in prison.2 Through much of the 1950s and 1960s, Seattle had only one black police officer.3 In 1955, the Mayor’s Advisory Committee on Police Practices found a pattern of racial discrimination against African Americans by Seattle police, but the reforms that the Committee generated revolved largely around public relations and sensitivity training that did little to satisfy the Department’s African American critics.4

Seattle was not unique in this regard. Black and other minority communities have long been the recipients of police harassment. Studies performed in the 1960s showed that police attitudes reflected the feelings of their surrounding community and that police used different standards of law enforcement depending on the race of the suspect.5 Although the poor and youth had more interactions with police in the 1960s, the average black citizen was more likely to be brutalized.6 Early in the Seattle campaign the Watts riot in Los Angeles in August 1965 alerted cities nationwide that ignoring the problems of their black communities could prove disastrous. The riot in Watts was preceded by a history of employment discrimination, housing discrimination, and poverty and was ignited by allegations of police brutality, not unlike the events in Seattle.

The Reese Incident

Robert L. Reese, a 40 year old black resident of Seattle’s Central District, died at 3:31 a.m. on June 20th, 1965. The events leading to his death were debated, but it was the response of the local police department and city government that ignited a civil rights confrontation. Certain people in Seattle saw the inquest and subsequent trials as justice doing its job while others saw in it the discrimination black Seattleites had lived with for too long.

In the Linyen Café, two off-duty policemen and their wives dined in the early morning hours of June 20th. Officer Frank Junell and Officer Harold Larsen and their wives had been drinking at various restaurants and cocktail lounges before they stopped at the small Chinese restaurant in the Central District. Also having dinner were two black women and two black men who testified that they heard the officers make derogatory racial remarks. The women, Doris Blood and Margaret Loften, reported hearing one man, identified as Officer Junell at the trial, say “I can’t eat comfortably around a bunch of niggers.” When one of the white women tried to get the man to be quiet, he said, “Just show me a nigger – any nigger in here – and I’ll kill him, I’ve got a gun,” and later, “I’m going to settle the bill, after all I’ve got my gun.” 7 Uncomfortable hearing those remarks, the two black women left. “To tell you the truth - I was scared,” Blood told reporters.8 On their way out, she mentioned to another patron, Osborne Moore, a black man, what they heard from the white men’s booth.

Osborne Moore had heard some of the remarks himself. Upset, he called Robert Reese’s house where a group of men were having a few drinks. Moore told them “there could be trouble at the restaurant,” and the men at Reese’s house drove down to the restaurant. Upon entering, they heard one of the officers later identified as Junell say “Here come some more niggers.” The men confronted the officers with their fists and a short brawl took place, during which Officer Larsen was briefly knocked unconscious. The officers were off-duty and out of uniform.9

Officers Larsen and Junell claimed the attack in the restaurant was totally unprovoked: “I was just bending down to take a bite of food when everything in the room seemed to explode in a bright flash and then I blacked out” Larsen told reporters. He came to and “they were slugging both of us. One was getting ready to slug Roberta [his wife].” News reports say anywhere from four to eight black men took part in the beating. Junell said, “Everything happened so fast I can’t recall anything that happened after that until I was out on the street.”10 Both reported that Junell was hit first. Larsen suffered from a cut on the back of the head, a black eye and two fractured ribs.11

When the fight stopped, the black men went outside, followed by the officers. Exactly what happened or why is not clear, other than the fact that Larsen shot five times at one of cars, killing Robert Reese with a gunshot wound to the back of the head. Witnesses to the beating and the shooting disagreed about whether the officers identified themselves as police officers, whether they spoke to the black men after the beating, and whether Larsen was drunk when he shot at the car.

On June 22nd, the coroner called for an inquest into Robert Reese’s death to clear up the events of that night and to determine if there was cause to shoot Reese. Depending on the outcome of the inquest, the King County Prosecutor’s Office would decide what charges to bring and against whom.

The inquest began on June 29th; over a dozen witnesses were called and the evidence was presented to a jury of six people without ties to the police department. Local newspapers extensively covered the shooting and the inquest, printing parts of the testimony from the attackers, the officers, and the witnesses. Weldon Boyland, the man who knocked Larsen unconscious, said that while the white man probably was not expecting to be hit, “He should have figured I was going to hit him when he called me a nigger.”12 The waiters, restaurant owner and two Asian patrons testified that they heard no racial remarks. Throughout their testimony the two officers denied making any derogatory remarks, “This is one thing that has been drilled into every man in the entire department not just once but continually. We are forbidden to either speak or act in any manner fostering racial prejudice. We are proud that we regard everyone alike, no matter what the color, race or creed,” Larsen explained.13

Admitting to the beating, James Williams said that after the brief clash, Officer Larsen offered to shake hands and forget the whole thing. He also testified that he never heard them identify themselves as policemen. Osborne Moore, driver of the car in which Reese was shot, said “If they’d identified themselves this whole thing would never have happened…I think he was shooting just to be shooting.”14 When asked at the trial why he did not attempt to arrest the men immediately after the beating, Officer Larsen said that after being unconscious it took a few minutes to “clear his head.”15

A crowd had gathered outside and when someone pointed out to the officers who had been involved in the beating, Reese and the other black men began to run away from the restaurant. They got into a car and began to drive away. Larsen testified that it was then he called out for them to stop and identified himself as a police officer. When the car kept going, he claimed he shot five times aiming at the rear tires.16

Most of the inquest focused on the amount of alcohol consumed and the use of the word “nigger”, but the attorneys also asked why Junell or the other officer who came to the scene did not use their guns. Junell said Larsen was closer. Officer Marion, who was on-duty at the time, testified that his nightstick was in the hand he uses for shooting and Larsen was standing in front of him anyway.17 “It is regrettable this had to happen and I know everybody on the force will feel the same way because someone was killed, but I felt it was my duty to stop them,” Larsen explained. Junell added, “We wanted to stop them because we felt this was really a felony and they should be stopped.”18 Prior to 1985, federal law and most state laws allowed any force necessary to prevent the escape of a suspected felon fleeing arrest: it was up to the officer’s discretion to use deadly force or not. Junell’s claim that the assault was a felony was possibly the reason, although it was never explicitly stated, that Larsen’s use of a gun was not the focus of the inquest.19

Because of the great degree of conflicting testimony, some people questioned whether any of the evidence was conclusive enough to lead to any jury decision. But on June 30th, the jury gave their verdict, deciding that the cops had been drinking but were not so intoxicated as to impair their judgment. They also found that the officers had been assaulted and the officers had used offensive language first. Lastly, they decided that Larsen did identify himself before shooting.20 Robert Reese’s death was deemed an excusable homicide: “an act committed by accident or misfortune in doing a lawful act by lawful means with ordinary caution without any unlawful intent.”21 Some interpreted the verdict as saying the murder was justified, as though the officers had every reason to shoot at the car speeding away. Since some testimony suggested the officers may have failed to identify themselves when they had the chance, or that they were drunk and had provoked the altercation, it hardly seemed like justice.

Based on the jury’s verdict of excusable homicide, King County Prosecutor Charles Carroll did not bring any charges against Officer Larsen. He did charge Officer Junell with provoking an assault. But he saved his harshest punishment for the four black men involved in the fight— James Williams, Osborne Moore, Weldon Boyland, and Leroy Head— each of whom he charged with third degree assault. Officer Junell was found innocent while the others were all found guilty and sentenced to serve 90 days in prison. During Junell’s trial, information came out that showed witnesses and evidence had been concealed from the original inquest. This appeared to support the belief that the police department and other city officials were trying to cover up misconduct and protect the officers. The Prosecutor did not see this as reason to prosecute the officers, and said the witnesses would not have changed the outcome of the inquest or the trial of the four black men since their testimony did not add any new information.22

Police Chief Ramon, while not acknowledging any wrongdoing by his officers, did mildly reprimand Larsen and Junell. Acting as chief of police while Ramon was out of town during the inquest, Assistant Police Chief Rouse suspended both officers. However, the suspension was for only eight days and become another example to the black community of how the two officers were getting off easy. But when Chief Ramon returned, he extended the suspension to 30 days, telling reporters on July 7th that the actions of that night were not “an acceptable level of performance” for the two officers, but that his decision in no way implied the guilt of Officer Junell who had not yet gone on trial for provoking the assault.23

Two days after announcing the extended suspension, Ramon drafted a memo to employees of the Police Department listing the existing departmental policy on discussing or using language likely to upset someone’s beliefs or meant as an insult. “Every member or employee of the Seattle Police Department must recognize that insulting, disparaging, ridiculing terms or language is the cruelest action one person can take against another and as representatives of government, must never use any expression which is offensive to other people.”24 While he never admitted that his officers may have provoked the black men on the night of June 20th, he made a previous statement at a February, 1965 City Council meeting that he believed at least 90 percent of the police force was racist to some degree. This suggested that he may have been aware of what really happened that night and perhaps community pressure was not the only reason for extending the suspension of the two officers.25

In addition to suspending the officers involved and reminding the force of their non-discrimination policy, Chief Ramon also made changes to the police department policies. Many people in the community cried out that it was irresponsible for officers to carry weapons while drinking and that the combination of the two led to the death of Reese when it might otherwise have been simply a brawl. Because policemen were considered on-duty at all times, they carried their weapon even when officially off-duty so that there were more officers out enforcing the law or protecting the public. Although Ramon claimed that the policy was already under review and would have been revised soon anyways, it was less than three weeks after the shooting on July 10th when he officially changed the policy. From then on officers did not have to have their guns on their persons when they were participating in social engagements or recreational activities where it was impractical to wear a gun.26

Civilian Review Board as Civil Rights Issue

But the reforms that Carroll and Ramon sought following the Reese shooting did not satisfy civil rights movement activists. To civil rights groups like the Central Area Committee for Civil Rights (CACRC), unrest after the inquest verdict was one more reason to push for a transformation of the relationship between police and the black community.

Civil rights leaders had already been campaigning along with other civil rights groups for Seattle to revise certain police department policies to reduce officer discrimination and abuse. Mutual suspicion and mistrust along with nationwide racial tension led CACRC leaders to request a meeting with police chiefs and Mayor Braman in August of 1964. They wanted to make sure that “the meaning and implications of this [national] unrest be fully comprehended by the law enforcement agencies, the civil rights groups and others.”27 Forty years later, Bishop John Adams, who had been pastor at First AME Church and Chair of the CACRC, recalled that previous claims of police brutality and harassment had received little to no response from the police department or municipal government: “I never had any confidence in the Seattle Police Department.”28

The January before the Reese shooting, the Washington Chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) petitioned the Seattle City Council to have a hearing on police practices. Specifically they wanted to address numerous allegations of police brutality and the lack of response from the Police Department, Mayor’s office or City Council. One man testified that he had witnessed beatings and instances of misconduct inside the department building and the jail. A juvenile claimed to be beaten while inside the jail, an officer was convicted of assault and other officers lost civil suits for brutality and yet all of them remained on the police force. The ALCU sent notices to other civil rights groups hoping to bring enough supporters to offset what they knew would be considerable hostility to this testimony brought in by the PoliceDepartment. “Public concern and support of our petition must be clearly demonstrated to the City Council if any further action is to come from that body.”29 The further action desired was an independent investigation into the use of force by the police, with the ultimate goal of creating a citizen-staffed agency called a police-review board where citizens could bring complaints to have them investigated by an impartial committee rather than by police officers themselves.

But while they did get a hearing before the City Council, CACRC and ACLU’s advocacy for a police review board was firmly rejected. Police Chief Frank Ramon, Mayor J. D. Braman, and King County Prosecutor Charles Carroll all maintained that there was no validity to the accusations of police misconduct. When the various brutality claims were voiced, Chief Ramon suggested that since each of the claimants was ultimately convicted of the charges they were arrested on, these accusations were simply “tactics used to gain sympathy in their defense.” Ramon, Braman, and Carroll argued that an independent review board was unnecessary and would “weaken the administrative responsibility of the Mayor and weaken police morale.” 30 The City Council passed a Resolution on March 13th, 1965 stating that procedures for making and reviewing complaints against the Police Department were “adequate” and that there was “no necessity at this time for establishment of additional boards or offices to protect the public.”31 In their newsletter, the ALCU reported on the hearing and how “the implications of this testimony seems to be that since no complaints against the Seattle Police Department are ever valid, there is no need for any kind of formal complaint procedure.”32

Obviously civil rights groups were displeased with the outcome. “Extremely short-sighted,” cried CORE. “Apparently the City of Seattle would rather wait until it has the insuperable problems of Philadelphia, Chicago, and New York before it begins to think about preventative measures.”33 But just when City leaders thought the issue was dead, the Reese shooting encouraged CACRC and other civil rights groups to keep fighting.

Community Response

Coming just three months after the City Council refuted calls for a police review board, Officer Larsen’s shooting of Robert Reese triggered an immediate public reaction, especially in Seattle’s African American community. Letters to the Seattle chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), which actively promoted the subsequent Freedom Patrols, demonstrated a range of community opinion. Somewere upset about the police department policy that required off-duty policemen to carry their guns. They felt this was irresponsible when off-duty officers were drinking. Others took care to voice their displeasure with all the people involved in the incident, including one letter that said: “five of our brothers were called from a drinking party and ganged up on two men while dining. Anyone who is attacked in this manner is entitled to defend hisself, and we are lucky they did not kill all five in their defense.”34 In another letter to CORE, one man wrote fiercely, “There have been and are now thousands of negroes who have served years of imprisonment for trivial offenses compared to the wanton killing of Mr. Reese, by officer Larsen. Equitable justice begs that he be made to pay for his crime, as any other criminal is compelled to undergo expiation for his.”35 Norma Pinfield wrote that

“Because the officers instigated this brawl by their derogatory remarks, I believe they should be held responsible for the death of Robert Reese. It is of my opinion that unless a man be treated with respect and dignity – the dignity which belongs to him as a fellow member of this human race…how is he supposed to act. It’s also hard to be a white American and live in 1965 for it embarrasses me to see what I supposedly represent. How too can I hold up my head?”36

Sensing community outrage, the Seattle Times editorialized that events surrounding the shooting “require full investigation by an impartial body.”37 In response, citizens sent the Times many letters of support for the Police. Frances Medley wrote that “I am totally opposed to the establishment of a police-review board and harassment of the local police who have simply been trying to do their duty.” Mrs. R.H. McGregor opined, “This is an ill-advised maneuver…Effective law enforcement could be damaged and the orderly processes of community life could be reduced to petty bickering.”38

Not everyone was against review boards or supported the police in the Reese case. A 17 year old young man from the Central District wrote to the Times that “If Seattle had the kind of police force they could be proud of, this incident wouldn’t have happened…This should be a thought-provoking eye-opening thing for everyone.”39 The University of Washington Daily newspaper editorialized, “The public has a right to investigate, review, and control its local police, and at the same time a duty to respect and support it. It cannot be expected to support a public agency that protests public investigation.”40

Soon after the shooting, and even before the inquest was complete, civil rights groups began to voice their concern that justice would not be done. CACRC coordinated the campaign. Comprised of many of the most influential community leaders of the Central Area, CACRC included Rev. John Adams; Rev. Samuel McKinney of Mt. Zion Baptist Church; Edwin Pratt, Director of the Seattle Urban League; Charles V. Johnson, president of the local NAACP; and Walter Hundley, director of Seattle CORE. As soon as coroner announced he would hold an inquest, CACRC told the media that they were willing to wait and see the outcome before deciding what action to take. The verdict came in on July 1st, along with Prosecutor Carroll’s announcement that he would be filing charges against Junell and the four black men, but not Officer Larsen. The very next day, CACRC declared it was going to hold a public meeting on July 10th to plan the community’s response to the verdict, the Prosecutor, and the Police Chief.

The day after the July 10th community meeting convened by CACRC, the group revealed to the media the outcome of that meeting, requesting five things. First CACRC, on behalf of the people of the Central District, insisted that Larsen and Junell be removed from the force or at least transferred out of the Central Area permanently. Second, the Mayor, City Council, and the Police Department needed to formally state a policy of non-discrimination. Walter Hundley explained that “Beneath the problem is the behavior involved – the derogatory remarks toward minority groups.” Acknowledging that policies need to be enforced in order to be effective was the third request. Fourth, they wanted a professional analysis of police training and practices performed by an outside party. Lastly, CACRC asked for the creation of a liaison between the police and Negro community. Explained Charles V. Johnson, “We are attempting to solve problems and create a better climate between police and citizens.”41

Freedom Patrols come to Seattle

Prepared for the city to ignore their requests, CACRC had already organized their plan to induce a response. During the meeting on July 10th at Mt. Zion Baptist church, over 500 attendees agreed with CACRC’s plan to pursue both direct and indirect actions for the purpose of getting a more comprehensive investigation of the Reese incident, creating a review board, and stopping police brutality against blacks. On July 11th, they announced to the press they would begin their own “walking civilian review boards,” or “freedom patrols.” Over 200 people volunteered to take part in non-violent observation of policemen in the Central Area. Teams of two to three people would follow policemen on their beat, making sure no regulations were broken, unwarranted force was used, or illegal activities took place. Assistant Police Chief Rouse called the idea “ridiculous” and “juvenile.”42 Dr. John Adams explained that these patrols looked to document police brutality and would go on until their demands were seriously considered and justice handed out.

It was Reverend John Adams’s idea to create the Seattle Freedom Patrols. But as he acknowledged in a recent oral history interview, it was not an original idea. His father, a minister in Columbia, South Carolina, had created citizen patrols in the 1930s to follow the civilian and military police who were reportedly harassing the local black community around Fort Jackson. “I brought the tactic and used it here in Seattle ,” Adams recalled.43

The freedom patrols in Seattle were to be unequivocally nonviolent. “If they use abusive language,” Adams cautioned the Freedom Patrolers, “smile at them and write down their badge numbers. If there is unwarranted use of force, let them push you backward so you can write down their names and badge numbers.”44 A lot of planning went into these patrols to make sure they stayed nonviolent. CACRC also told the media many times that they were not going to interfere with the police’s work: they simply would be observing them.

Before the patrols began, CACRC arranged a Steering Committee of the Citizen’s Committee on Police Practices to brainstorm what they would need to complete this type of action. Legal advice and publicity were the main focuses. The ACLU prepared a memo explaining some of possible problems of trying to follow and observe police officers. They suggested trying to observe the jail and the areas where beatings occurred according to previous claims of brutality. But, the memo stressed, it was important to not interfere and to stop asking questions if the patrolman tells you to. Although optimistic about the planned action, the ACLU cautioned, “Such activity by an untrained citizen is extremely dangerous. A policeman, discovered in an act of wrong-doing, would have an increased motive to bring criminal charges against the citizen.”45 The guidelines CACRC’s leaders gave to patrollers reflected the advice from the ALCU. They told patrollers not to be hostile, nor to respond to hostility. They weren’t to use physical violence, but could try to prevent it with words or by using their own body as a shield. They were told to always carry identification and Freedom Patrol insignia. Also they were to have coins for the pay phone in order to check in hourly with the coordinating staff at the CORE home office. Lastly, they were told not to carry anything that could be considered a weapon. 46

To garner publicity for the first night of the freedom patrols, Saturday July 24th, the patrollers were the leaders of the CACRC and the black community – ministers, lawyers, and businessmen. The first group of nine people included two women and one white man. They were to demonstrate for future volunteers how the patrols were to be conducted. In a style quite different from Black Panther patrols that occurred only a few years later, they dressed nicely, behaved appropriately, and the “the patrolling officers chatted frequently and in friendly fashion with patrols members.”47 After that first night, the majority of the rest of the patrols were handled by volunteers from the community who were accepted only after rigorous scrutiny. Patrollers had to be over 21, attend trainings on nonviolence, and had to fill out applications listing their employment, other organizations they were part of, give references and say whether they had ever been convicted of a felony.48

Media coverage of the first patrol gave Reverend Adams, the regular spokesman for these actions, another chance to explain to the rest of the Seattle community the purpose of these patrols: “we are concerned about building up public sentiment, convincing public officials that there is brutality and getting documentation that will stand up in court.”49 Chief Ramon told the media that these patrols would have no effect on the police because there was not anything devious or dishonest going on.

At first there was no attempt to hide anything about the patrols. CACRC publicized when they would be on patrols so that everyone, including the police, would know when they were to be followed. The idea as Adams explained it was that the patrols meant to serve as a reminder “to big brother that his little brother is watching him.”50 Simply knowing that the community was paying attention and documenting their actions would be enough to reduce the incidents of police harassment. But six weeks after the start of the patrols, the frequency diminished. Rev. Adams told the media that they were “deliberately seeking to create uncertainty” so the police would not know when to expect them.51

The patrols would continue for the next six months but with the reduced frequency and declining participation. Initially, 15-20 people were expected to be on duty on each patrol which took place primarily on Thursday, Friday, and Saturday nights.52 The patrols focused on police beats in the Jackson Street and Madison Street areas where a lot of restaurants, taverns, pool halls, and some prostitution were located. Within the first six weeks Adams told reporters that they had already seen situations of inappropriate conduct by police officers. Police Chief Ramon denied it.53 Unfortunately, accounts of what exactly occurred during these patrols are not well-documented and although news articles suggest that CACRC had complaints to bring to the attention of the police department, no records were found describing the direct effects of these patrols.

Newspapers mention the patrols as late as October 13, 1965 and then according to CACRC historian Larry Richardson, the patrols died out.54 However, CORE newsletters and meeting minutes reference the patrols and call for more volunteers in July 1966 and October 1966, but documents fail to show if the patrols were continuous since 1965. Ed O’Keefe took over coordinating the patrols in 1966 and in July of that year wrote in a newsletter that patrol “enthusiasm and participation had dropped off alarmingly.”55 Enthusiasm seems to have been a problem with the patrols early on because in August 1965, just a month after beginning, CORE announced a meeting to “re-invigorate and escalate” the patrols and for interested people to help produce more patrols and “more effective action.”56

From Freedom Patrols to Civil Rights Commission

The publicity brought by the freedom patrols was used to elucidate other plans meant to accomplish the five goals of CACRC. While the patrols were a form of direct action of to stop police brutality and symbolically call for legislative change, there were other actions using legal channels and public investigations which were also used to influence the Police Department and the city into considering their requests.

Police accountability advocacy also took on a greater urgency following the Watts riots in August,1965. Advocates of police department reform worried aloud that the similar events of the Reese shooting and the problems of police brutality that ignited Los Angeles would someday lead to riots in Seattle as well. City officials tried to alleviate those worries by explaining that they had a plan in place to handle a possible riot, and that they believed the majority of Seattle’s black community to be “law-abiding, fine, responsible citizens.”57 Not everyone felt as secure though, “It is doubtful the Los Angeles officials, both police and political, had any inkling of the explosive nature and the true feelings of people in Watts District prior to the riot,” black reporter Donald Smith wrote for the Seattle Times in a series exploring racial problems. “And it is doubtful that officials in Seattle know the true feelings of the Seattle Negro.”58 He also wrote that “Seattle Negroes, in the main, feel they have been thwarted by what they call the ‘white power structure’ including mayor, city council, certain leaders in the white community and the news media.”59

Like his Police Chief, Mayor Braman avoided acknowledging a department problem or individual officer guilt, but he too tried to address some of the community’s concerns. The mayor’s response to the shooting first appeared as though he would make sure evidence would be reviewed critically and impartially. The mayor said that after the inquest verdict, he would put together an investigative team and meet with civil rights groups to discuss what else might need to be examined. Civil rights groups received this “promise” favorably, commending Mayor Braman for his decision even though he stressed that this was only a possibility and that it would not lead to any permanent independent investigative team (such as an independent review board). In July after the inquest ended, Braman appointed a committee to look into police training methods in relation to minorities. The committee’s conclusion was that while the police currently spent only 2-3 hours out of three months training cadets for contact with minorities or other communities, they could use an additional 30 hours of training in human relations.60

Possibly in response to CACRC’s campaign or to the Watts riot, the Mayor also decided to implement a special police unit that dealt primarily with the community members. He called it the Community Relations Unit and it was compromised of police officers who had received education in subjects like sociology, psychology, community development and so on. Established in September, the small five-person unit of the police department was supposed to “establish meaningful lines of communication with Negro community, to listen to grievances, clear up misunderstandings, bring about better cooperation.”61 In a meeting with CORE in March 1966, one of the Community Relations officers explained the unit’s purpose. He said that they reported directly to the Police Chief and could immediately impact cadet training practices with what they learned from the community and that the unit was established when Seattle realized it did have a problem with race.62 Likewise, the King County Sheriff agreed to meet with CORE to talk about complaints made and the Community Relations Unit of the Seattle Police Department sought out meetings with CORE, acknowledging that these civil rights groups represented the community and the community could no longer be ignored.

Seattle Civil Rights movement leaders saw these measures as too little, too late. On September 3rd, CACRC announced it would ask the United States Civil Rights Commission to come to Seattle to investigate the Reese incident as well as other police misconduct complaints and civil rights violations. The petition accused the Seattle city government of being “unresponsive and irresponsible” with “what seems to be the attitude of Seattle officials that the police department can do no wrong.”63

In addition to the petition, they wanted to continue the freedom patrols and establish a complaint board of their own. People would be able to go to CACRC’s board to report incidents of police misconduct. The civil rights groups would look into the validity of those claims, help with legal action for those incidents that were strong enough and also hold monthly public hearings on the complaints.64 Without knowing the true extent of the problem, officials could avoid acknowledging the racial problems of Seattle. But by allowing residents a more welcoming place to bring concerns about police actions, more people would be likely to file complaints when before they may have wanted to avoid going to the police department to file complaints. It doesn’t appear that this plan ever got off the ground, however, as CACRC increasingly sought the help of the federal government to change community-police relations.

While finding it difficult to get adequate attention about police harassment with only the patrols, CACRC vamped up efforts to secure the attention of the federal authorities. In the months after the trial and the launch of the patrols, a large amount of the focus of the CACRC was turned to the petition for the Civil Rights Commission. Over a thousand signatures were sent to the Commission in October, warning that “we are sitting on a tinderbox here.”65

In what at first appeared to be the greatest success of the movement to revise police policies and confirm the existence of discriminatory practices, the Commission agreed to hold public hearings in Seattle. The Washington State Advisory Committee to the United States Commission on Civil Rights Commission met with members of the black community on January 21st and 22nd of January 1966, exactly a year after the unsuccessful City Council public hearing. Originally the purpose of the visit was to look into the Reese incident as well as other civil rights violations, but just days before the hearings were to begin, word was sent that the Commission was not to hear evidence about the Reese case. Because the shooting was still under investigation, according to the telegram, no testimony should be heard, although people would be allowed to discuss how the event affected them personally. This was perhaps disappointing, but there were plenty of other violations and incidents of discrimination to tell the government representatives. Witnesses talked about harassment from police toward interracial couples and toward blacks driving nice cars. John Cornethan, Seattle CORE chairman at that time, described that while the reaction from the black community to the Reese incident led to a decreased number of brutality reports, incidents of harassment and discrimination were already on the rise.66 The Commission made no statements about the Reese shooting, but one spokesperson did say they would recommend labor union discrimination be looked into by a federal grand jury for violations of the Civil Rights Act.67

By the very next January, 1967, two more shootings by the police brought further attention to police practices. Two juvenile deaths and the Reese shooting led Democrat Sam Smith, an African American Washington State Representative representing Seattle’s Central District, to draft legislation calling for an examination of the policy of firearm use in juvenile arrests and provided that petitions of 50 or more signatures would force the coroner’s inquest be moved to the Superior court. The reasoning was the controversy and lack of public confidence in the impartiality of coroner’s inquests.68 The legislation failed to pass.

Conclusion

For two years, Seattle civil rights groups campaigned to change police and city policy to ensure fairness in the local criminal justice system. Repeated calls for independent police review boards were shot down as potentially damaging to police authority. The black community’s skepticism toward the justice system was ignored. In looking at the events of 1965, from the City Council hearing to the Civil Rights Commission hearing a year later, only when the threat of violence or rioting was apparent did the police and the municipal government appear to give consideration to the needs and requests of the black community. Richardson credits CACRC’s freedom patrol campaign as being a constructive outlet for the racial tension of the district, helping to prevent riots or other violent unrest common to many cities in the 1960s.69 Even the Mayor acknowledged that in the midst of three “crises,” including the Reese shooting, a visit from Stokley Carmichael, and the Eddie Ray Lincoln shooting (when an unarmed black man was shot in the back by police officers after running from what the officers believed was an attempted car theft) the black community kept their cool and were to be commended for that.70 But Braman seemed unable to connect his stifling of police-community relations reform with the development of the Seattle Chapter of the Black Panther Party two years later. The Panthers, in much more dramatic fashion, would make police accountability its signature issue, monitor the Seattle police, assume community police functions, and even hold community hearings on police shootings of its members.71

When considering the Lincoln shooting and the death of the two juveniles that led to Representative Smith’s legislation, it does not appear that the campaign against excessive police force was successful. But police harassment is a problem that exists today and it would be too much to expect that one year’s campaign could rid a city of racist stereotypes. At the least the patrols were successful in bringing media attention highlighting the problem in way that city officials were able to take a few steps toward correcting. More than just observing patrolmen, the CACRC’s freedom patrols and complaint committee served as a liaison between the police and the black community who too often saw the police as their enemies. From pairs of armed ministers in South Carolina to nonviolent Seattle community activists to black power militants, confronting police through freedom patrols “was a way to break police control of community and encourage community to develop itself.”72 While Seattle may not have ever gotten the independent police review board desired (and recommended as recently as 1997 by the Seattle Human Rights Commission), Mayor Braman’s derisive comment in 1965 to a Central Area youth group advocating for a citizen review board, “Not one single inch of progress has been made by groups like you,” was proven wrong in 1965 and has been time and again since.73

Copyright © Jennifer Taylor 2006

HSTAA 498 Autumn 2005

1 http://www.historylink.org/_output.cfm?file_id=273

2 http://www.historylink.org/_output.cfm?file_id=3477

3 http://www.historylink.org/_output.cfm?file_id=1165

4 http://www.historylink.org/_output.cfm?file_id=2938

5 Jerome H. Skolnick, The Police and the Urban Ghetto (Chicago: No. 3 Research Contributions of the American Bar Foundation, 1968), Pg 8.

6 Michael Lipsky, Law and Order: Police Encounters (Trans-action Books, Aldine Publishing Co., 1970), Pg 5.

7 Seattle Times, August 16, 1965, “Beatings by Negroes were Unprovoked, say Officers”.

8 Seattle Times, August 17, 1965, “Witness Quotes Insults at Trial” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

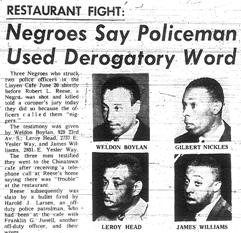

9 Seattle Times, June 30, 1965, “Negroes Say Policeman Used Derogatory Word” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

10 Seattle Times, June 21, 1965, “Assault in Café a ‘Nightmare’ Say Officers” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

11 Seattle Times, August 16, 1965, “Beatings by Negroes were Unprovoked, say Officers”.

12 Seattle Times, June 30, 1965, “Negroes Say Policeman Used Derogatory Word” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

13 Seattle Times, June 21, 1965, “Assault in Café a ‘Nightmare’ Say Officers” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

14 Seattle Times, June 30, 1965, “Parade of Witnesses Reconstruct Details of Fatal Shooting” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

15 Seattle Times, August 16, 1965, “Beatings by Negroes were Unprovoked, say Officers”.

16 Seattle Times, June 29, 1965, “Liquor Dominates Testimony at Inquest Into Fatal Shooting” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

17 Seattle Times, August 17, 1965, “Witness Quotes Insults at Trial” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

18 Seattle Times, June 21, 1965, “Assault in Café a ‘Nightmare’ Say Officers” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

19 Dean J. Champion, Police Misconduct in America (Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO Inc., 2001), Pg 52-53.

20 Seattle Times, July 1, 1965, “12 Queries Answered by Jury In Reaching Inquest Verdict” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

21 Photocopy of RCW definition of excusable homicide, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

22 Larry Richardson, “Civil Rights in Seattle: a rhetorical analysis of a social movement.” (Unpublished PhD Dissertation, WSU, 1975), Page 135.

23 Seattle Times, July 7, 1965, “Two Policemen Receive 30-day Suspensions” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

24 Memo to Seattle Police Department, July 9, 1965, Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

25 ACLU of WA Newsletter, March 20, 1965, “Council, Chief fail to face Issues in Police Petition”. Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

26 Seattle Post-Intelligencer, July 10, 1965, “Chief’s Gun Edict: Off Duty Changes” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

27 Letter from CACRC August 12, 1964, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box 1, Folder “1964 Correspondence”.

28 June 24, 2005 Oral Interview with John Adams, adams.htm

29 ACLU Notice on Seattle Police Hearing, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

30 ACLU of WA Newsletter, March 20, 1965, “Council, Chief fail to face Issues in Police Petition”. Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

31 City of Seattle Resolution 20179, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

32 ACLU of WA Newsletter, March 20, 1965, “Council, Chief fail to face Issues in Police Petition”. Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

33 “CORE Hits Police-Board Turndown” Clipping, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality” Date Unknown.

34 Letter to CORE from J.M.P., Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box 1, Folder “1965 Correspondence”.

35 September 14, 1965 Letter to CORE, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box 1, Folder “1965 Correspondence”.

36 The Facts, July 16, 1965, Letters to Editor, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

37 Seattle Times, June 21, 1965, “Impartial Inquiry Needed”.

38 Seattle Times, June 24, 1965, Letters to Editor, Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

39 The Fact,s July 16, 1965, Letter to Editor Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

40 UW Daily, October 15, 1965, “but officer” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

41 Seattle Times, July 11, 1965, “Better Citizen-Police Climate if Goal, says NAACP Aide” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

42 Seattle Times, July 11, 1965, “Civil Rights Group Plans Action: ‘Freedom Patrols’ to watch City Policemen” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

43 June 24, 2005 Oral Interview with John Adams, adams.htm

44 Seattle Times, July 11, 1965, “Civil Rights Group Plans Action: ‘Freedom Patrols’ to watch City Policemen” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

45 ACLU Memo, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

46 Nonviolent Discipline for Patrols Memo, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

47 Seattle Times, July 25, 1965?, “Freedom Patrols Begin: Nonviolence Stressed” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

48 Application for Freedom Patrol, Date Unknown, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

49 Seattle Times, “‘Freedom Patrol’ to Join Policemen on Beats Saturday” Date Unknown, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

50 Seattle Times, July 25, 1965?, “Freedom Patrols Begin: Nonviolence Stressed” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

51 Seattle Times, September 2, 1965, Herb Robinson Commentary “Freedom Patrols”, Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

52 Phone Interview with Charles Johnson by Jennifer Taylor, December 1st, 2005.

53 Seattle Times, September 2, 1965, Herb Robinson Commentary “Freedom Patrols”, Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

54 Larry Richardson, “Civil Rights in Seattle: a rhetorical analysis of a social movement.” (Unpublished PhD Dissertation, WSU, 1975), Page 137.

55 Seattle Corelator July 24th 1966, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter Corelator 1961-1968”.

56 Seattle Corelator August 1965, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Newsletter Corelator 1961-1968”.

57 Seattle Times, “Area Prepared for Riots But None Expected, says Carroll” Date Unknown.

58 Seattle Times, August 16, 1965, “Seeds of Potential Riot Present Here, Writer Believes” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Clippings”.

59 Seattle Times, August 15, 1965, “Seattle Racial Image Called Tarnished” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Clippings”.

60 Seattle Times, September 15, 1965, “Police Unit for Racial Problems is Established” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

61 Meeting Minutes, March 8, 1966, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

62 Meeting Minutes, March 8, 1966, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

63 Petition to U.S. Civil Rights Commission, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #8, Folder “Freedom Patrols”.

64 Seattle Times, September 3, 1965 “Negroes protest abuse: Federal Intervention in Policing is sought” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

65 Letter to U.S. Civil Rights Commission, October 12, 1965, Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

66 Seattle Times, January 21, 1966, “U.S Grand-Jury Probe Urged at Rights Hearing” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

67 Seattle Times, January 21, 1966, “U.S Grand-Jury Probe Urged at Rights Hearing” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #11, Folder “Police Brutality”.

68 Seattle Times, January 11, 1967, “Laws Asked in Wake of Shootings” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.

69 Larry Richardson, “Civil Rights in Seattle: a rhetorical analysis of a social movement.” (Unpublished PhD Dissertation, WSU, 1975).

70 Seattle Times, September 5, 1967, “Mayor Praises Negroes for City’s Peace” Seattle CORE Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #1563, Box #2, Folder “Clippings”.

71 display.cgi?image=bpp/news/ST_oct18-69-p35.jpg

72 Larry Richardson, “Civil Rights in Seattle: a rhetorical analysis of a social movement.” (Unpublished PhD Dissertation, WSU, 1975).

73 Clipping, Date Unknown, “Mayor, Youth Action Council Engage in Heated Discussion” Seattle Urban League Papers, University of Washington Special Collections. Acc #607-7, Box #24, Folder #42.