“Klansmen, you can make your power for the Klan felt every day. Newspapers the country over are feeling the pressure of Klan displeasure and are beginning to print favorable Klan news. Encourage them by subscribing and tell them why. If they won’t print good news about the Klan and insist on printing all the bad news, stop the paper and tell them why… When you see the Fiery Cross blazing on some hill over your town, remember the words of Christ: Be not afraid, it is I.”1

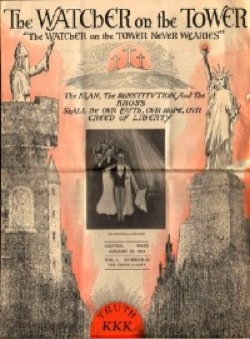

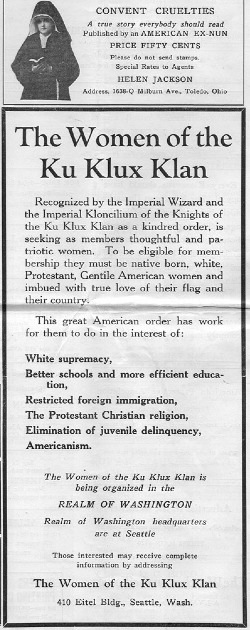

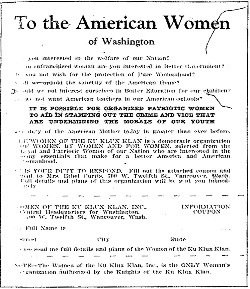

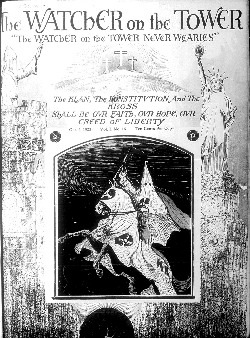

Most Americans have heard about the Ku Klux Klan at some point in their lives; however, it usually is the first Klan. Few people know that there was more than one version of the Klan and that each identified itself differently. Some Klan chapters in the 1920s published newspapers to gain support and spread their beliefs; one of these was in Washington State. The Seattle Klan newspaper, Watcher on the Tower, illustrates the Klan’s beliefs in Protestant Christianity, pure Americanism, white supremacy, manliness and fraternity, and how it saw these as the defining characteristics and representations of Klansmen.

Historical Background

There have been three distinct versions of the Ku Klux Klan in American history. The first emerged in 1866 in response to the Southern defeat in the Civil War. Fear and anger at the loss of freed slave labor led southern whites to rally around the idea of white supremacy. Klan members emphasized the threat to traditional American life that African Americans supposedly represented and exploited the still widespread belief that, although freed from slavery, blacks would always be inferior to whites and unfit for social or political equality… Whites claimed blacks needed them for survival and that left without guidance, they would undermine American morals and values and threaten law and order. The first KKK rallied public opinion in the South against Republican-dominated Reconstruction governments across the South. Using violence and intimidation, the Klan was instrumental in restoring “home rule” to the South. Support for the first Klan died out by the mid 1870s. This was partly due to measures taken by the federal government to suppress the group. More so, however, it was the success of white supremacy and the overthrow of radical Reconstruction that rendered the Klan no longer necessary in the eyes of many white southerners.

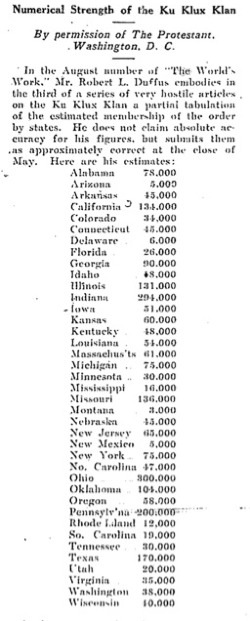

Decades later, years of massive immigration combined with the turmoil of America’s involvement in World War I to bring about a revival of the Klan that extended far beyond the Jim Crow South. Growing fears about communism and labor unrest after the Russian Revolution in 1917 and the wave of strikes that hit the nation after World War I inspired a backlash among some Americans under the banner of “preserving” American democracy. This new Klan broadened its focus so that it was no longer strictly about blacks, but rather Catholics, immigrants and anyone else deemed less than 100 percent American. The industrialization of America played largely to the fears that people experienced during the war. Not only was there a strong fear of communism, but also a concern that, as historian William Loren Katz writes, “world events were overtaking decent, God-faring folks.”2 The Klan of the 1920s focused largely on holding on to the old ways of life where people worked the land and focused on God and family.

The second Klan was created out of beliefs still lingering from the first Klan. One key component to gaining support for the new Klan was a novel by Thomas Dixon called The Clansman: A Historical Romance of the Ku Klux Klan. As a small child, Dixon witnessed a KKK parade which at first he found to be rather frightening. Reassurance from his mother sparked a lifelong image of Klansmen as noble knights. As he grew, he accepted the ideas of “racial purity and white power”3 and eventually went on to write his novel in which he portrayed Klansmen as gallant knights defending women and white southern honor. Later, Dixon met filmmaker D. W. Griffith and the two collaborated to create a movie based on Dixon’s novel, Birth of a Nation. The film was Hollywood’s first blockbuster, as more than 50 million people viewed it in the weeks following its release in late 1915. This audience included President Woodrow Wilson, who made Birth of a Nation the first movie to be screened at the White House. Griffith filmed in such a way that the film took on the appearance of a documentary, leading people to accept the movie as truth. The film portrayed the Klan as saviors against black rapists and helped instill both support for the Klan and representations of good whites and evil nonwhites.4

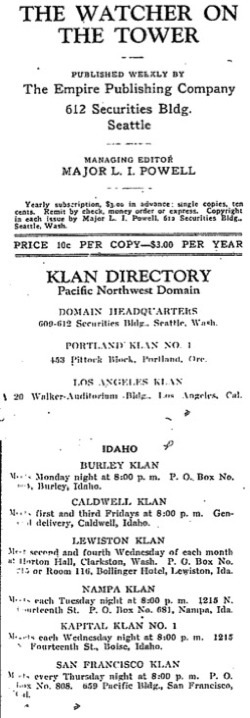

Birth of a Nation helped spark the revival of the KKK. Beginning in Georgia in 1915, the KKK spread from the eastern part of the United States westward to the Pacific.5 After the election of 1924, the KKK Imperial Wizard, Hiram Evans, headed west on a month long trip to inspire and survey the states west of the Mississippi River.6 Evans stopped in Spokane, Seattle, and Tacoma, where he received warm receptions. His visit helped build upon a fledgling Klan organization in Washington State founded two years earlier by Major Luther Powell. Powell had first started a Klan chapter in Oregon, which increased in strength throughout the early 1920s. When problems developed in the Oregon Klavern, Powell decided to go to Washington where there was still no developed Klan. Powell became King Kleagle of Washington State in 1922. In Washington, the Klan never became as prominent as in Oregon, the Southeast, or Midwestern states like Indiana, but during the 1920sWashington’s cities felt its presence.

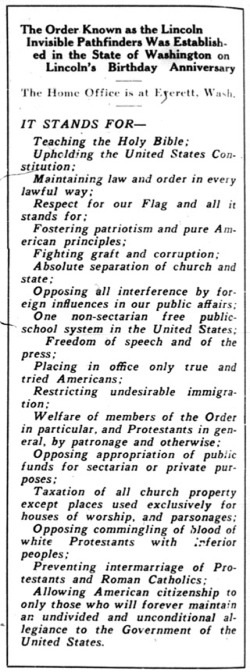

The Washington Klan established Watcher on the Tower, a weekly newspaper based in Seattle that reflected how Klansmen saw themselves as protectors and keepers of American society. Watcher on the Tower ran for three years, from 1920 to 1923, and like most newspapers, it included advertisements and local stories. By examining this local news source, we can see more clearly how Washington Klan members thought of themselves and others. Each portion of Watcher on the Tower reflected the identity of the Klan in four key areas: Protestantism, Americanism, White supremacy, and masculinity.7 Members of the Klan believed that they were the only true Americans and that it was necessary to protect against groups like Catholics, immigrants and those they believed were not “pure American.” This paper will start with an examination of the role of Protestantism in the worldview of the Washington State Klan as seen through the pages of Watcher on the Tower.

Religion and the Klan

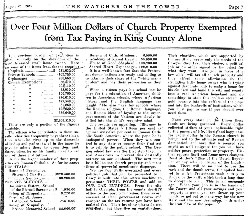

While religious beliefs had their place in the first KKK, it was the revival of second Klan in the 1920s that sparked a deep interest in religious identity. As an article in Watcher on the Tower explains, a KKK member’s “first allegiance is to his country and his flag that he may worship God in any manner that his conscience dictate.” But this stated belief in the freedom of worship applied only to Protestantism. Klan members rallied around the idea that America had been founded on Protestant ideals and that Catholics, Jews, and other religious groups were corrupting God’s word. They promoted the idea that “Protestantism spells freedom, intelligence, virtue and justice for all”8 and clung to the belief that they were soldiers of God united in their righteous purpose.9 Beliefs like this were popular among Klan members and non-members alike and, as a result, helped the Klan gain support. By cloaking their appeals in strong religious language, the Klan was able to convince many in the general public that the KKK stood for a Godly cause. Because of this, the Klan was able to get support from local community churches, which helped strengthen their identity and purpose. Being backed by a church made for a strong stance and spirit among Klan and community members. Many people did not necessarily support the Klan and all its beliefs, but with church support, many non-Klan church members did not disagree with anti-Catholic sentiments. While the Klan operated locally, nationally their foremost strategy was to win over Protestant clergy, which gave them tremendous strength.

Unlike the first Klan that focused its attacks on African Americans, the new Klan also looked at “offenders who were white,”10 which in practice meant Catholics received most of the religious hostilities in Washington State. Klansmen believed that Rome and the Vatican were ultimately undermining American democracy and that private Catholic Schools should be abolished. They saw Catholics as people with dual identities who placed their Catholic one before their American identity. Because Klansmen saw the Protestant religion as “based entirely upon the Word of God”11 and Catholicism as influenced by a corrupt Pope, they believed Catholics were teaching against the true word of God. For example, the July 1923 addition of Watcher on the Tower warned parents to “watch the text- books selected by … school boards” and to make sure that nothing “un-American creeps into them” because of the fear that Catholic propaganda would corrupt “the minds of young Americans.”12 Catholic propaganda meant promoting allegiance to Rome over America and, as the Klan saw it, overstressing the importance of loyalty to someone (i.e. the Pope) who was not an American citizen. The following article on the page went on to tell Protestant parents “it [was] wrong to allow children to be taught by Roman-Catholics.”13 Catholics also fell under attack with regards to schooling because of school bills that were meant to increase taxes. _Watcher on the Tower_noted that if one of these bills were to pass “it would be the knights of the Ku Klux Klan and other common people who will pay for it … not a cent of it will come from the Church of Rome.” 14 Klan members saw the passing of this bill as a way for Catholics to spread their “un-American” religion at everyone else’s expense.

Klansmen believed that the Vatican was always plotting against the people and that its “supreme purpose [was] the destruction of liberty.”15 As one Klansmen wrote in a Watcher in the Tower editorial, “The Roman catholic church is now, and has been, insidiously working to make America catholic.”16 Because the Vatican was not in America, the Klan played on the idea of Catholics as foreign, claiming “the land of the Pilgrim Fathers is being betrayed by free-booters and cut-throats from foreign shores.”17 Klan members rooted this Catholics-as-outsiders argument in American history. They claimed that Catholics were not among the first people to arrive in America and that even after they came, they were outcast because they wanted a share of America’s prosperity, but would not denounce their allegiance to Rome. By identifying themselves as the holders of true Americanism, the Klan justified its persecution and violence. In an article titled “our Liberties are in Danger,” _Watcher on the Tower_criticized Catholic religious practices that placed the church before their country and argued that this should bar Catholics from holding public office. “No man who cannot from his whole heart pledge undivided allegiance to the government of the United State should be permitted to hold any salaried office,” the paper wrote.18 This was part a push to get Catholics out of office and part an appeal to American ideals that people should love their county “first, last and best.”19

There was widespread fear that traditional beliefs and lifestyles were under attack from the changes brought about by different religions. As historian Shawn Lay writes, the Klan had tremendous “loyalty to orthodox Protestantism and a provincial fear of all things foreign.”20Watcher on the Tower helped stress the threats of both Catholics and Jews as alien threats who either pledged their allegiance elsewhere or were not Christian at all, and identifying Klansmen as true American “Soldiers of God.”21 Thus the ultimate purpose of opposition to Catholics and Rome was to help Klansmen identify themselves not only as morally pure, but also as more purely American.

Americanism and the Klan

Defining what it meant to be American was at the center of most Klan propaganda. Members claimed, “The Klan [stood] for all that is best in American life [and] no real American can give a fair, just or valid reason why any good citizen should not belong to it.”22The role of Watcher on the Tower was to spread the ‘spirit of Americanism’ across western Washington and to demonstrate why the Klan was a model of it. By aligning with mainstream conservative agendas on issues like temperance, crime, and immigration, the Klan tried to convince people that they shared the same beliefs in hopes of gaining continued and more widespread support.

The early 1920s were a time of change and uncertainty for many white Protestants, one which saw the birth of Jazz music, a strong push for women’s rights, a surge in immigration, and new restrictions on alcohol consumption. Many shared the Klan’s feeling that these and other developments were a deviation from family and community well-being. There was talk of recapturing “innocence” and “virtue,” things people felt were being challenged and disregarded. Prohibition was part of this movement. Nationwide, many people supported the idea of a ban on alcohol, and it provided the Klan with the opportunity to gain support through a common cause. Moreover, the Klan effectively linked alcohol consumption with immigrants. Along with alcohol, many white Protestant Americans shared the Klan’s belief that immigrants were the cause of many of society’s problems. They saw them as bringing in undesirable practices and beliefs, and sought to impose restrictions on immigrants as well.

The Klan used its arguments against Catholics to point out what it saw as problems within the government and to express its own brand of reactionary patriotism. There were Senators and Representatives in Congress who were Catholic, and the Klan claimed these people were the cause of corruption in the government because their first loyalty was not to America. This was a grave concern for the Washington Klan. It used Watcher on the Tower to extol the Constitution and government created by the Founding Fathers. Watcher on the Tower argued it was time for the “American people [to] now … defend the Constitution of the United States,”23adding that KKK members believed in the “old ways” where patriarchal order, home and family supposedly dominated American life. Klan members believed that they had “lived and prospered under [the] Constitution” and that America in the 1920s was departing too much from it. Watcher on the Tower ran articles that urged people to “give more attention to the Constitution,” saying “the document itself sustains our faith [and made Americans] the freest and greatest people in the world”24 and “that the American constitution is one of the most sacred documents and inspiring instruments ever.”25 The perceived need to bolster faith and trust in America during a time of uncertainty led the Klan to blame Catholics for the nation’s problems and define themselves as defenders of a mythical “American way of life.”’

Americanism was also promoted through support and enforcement of political changes like Prohibition. Klansmen spoke of themselves as morally pure and regarded drinking alcohol as a breach of these qualities. They fought with the government against bootlegging and alcohol consumption. This period in history was a time when many people were looking to restore American society back to the “days of old” by addressing societal problems. Because the Klan advertised itself as reforming a wayward society, it was able to gain support from those not directly associated with the Klan, but who supported and agreed with certain Progressive-era initiatives.

Along with its position on Prohibition, the Klan also wanted more police control and law enforcement. Watcher on the Tower ran an entire article titled “What the Klan does not stand for” in which the author, O. V. Davis, points out societal flaws not supported by the Klan. Davis noted, “we uphold so many things which have direct bearing on the continuance of our good government that many presumably good citizens are beginning to wonder and ask the question, what does the Ku Klux Klan oppose?”26 Davis then lists things like law breaking, lax police enforcement, race mixing, and Catholics in office as not to be tolerated. The Klan labeled such things “un-American” and in so doing was able to identify itself as the redeemer and purifier of America. Indeed, as O.V. Davis concludes, “a great house cleaning will be necessary to remove this threatening menace,” but that “the Klan has come to the rescue of our great nation.”27

Watcher on the Tower ran articles that modeled a Klansman as the utmost in American patriotism. At conferences, discussions would center on “the Klansman’s obligations as a patriot to his God, his country, his home and his fellowman,”28 instilling in their minds that they were the picture of pure one-hundred-percent-Americanism. Klansmen believed so strongly in their own purpose that they were convinced that “every good citizen will … understand they identify with their aim [and] give his support to the Klan.”29 Of course, this was not the case, especially in Washington State where the Klan never became a mass movement. However, what is important is that this is how the Klan saw itself and this vision was appealing enough to make an impact on the history of the state and the nation.

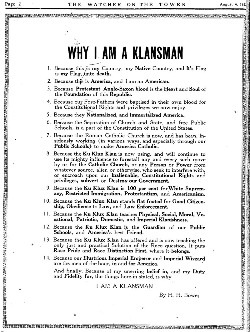

The Klan also played strongly to the idea of a lost country. It argued that foreigners were the enemy of American liberty and used both fear and guilt as a means of bolstering support by asking if all the Founding Fathers fought for would be lost in vain. Some of Watcher on the Tower’s most powerful pieces asked, “Why am I a Klansmen,” defining Klan members as the defenders of America and justice. An example of this can be found in Watcher on the Tower, where one writer answered the question by saying: “because the Ku Klux Klan stands flat footed for good citizenship, obedience to the law and law enforcement.”30 Presenting Klan members as law-abiding citizens and upholders of true Americanism brought the group’s purpose closer to home and reinforced the members’ belief that only the Klan could return America to its supposed foundations.

White Supremacy and the Klan

Rooted in the ideas of the previous Klan, the Knights also believed that the white race was endowed to rule over all others. According to Watcher on the Tower, “Protestant Anglo-Saxon blood is the heart and soul of the foundation of this republic.”31 As this quotation indicates, the Klan’s belief in white supremacy was bound up with the group’s broader appeal to patriotism, Protestantism, and Americanism.

White supremacy in America has a long history, dating back at least to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century justifications of slavery. During slavery, whites quickly decided that Christian conversion did not make slaves either free or equal. The same principle was updated in the 1920s by the KKK. Klan membership had many restrictions, but the easiest of all to see instantly was whether a person was white. While groups like Catholics and Jews were considered white, they were also considered foreigners, not real Americans according to Klan ideology. But what about Protestants from non-white ethnic or racial groups? White supremacy was used to attack and defame these groups.

In Washington State, these ideas spread with the revival of the second Klan and appeared often in the pages of Watcher on the Tower. For example, an August 1923 article claimed, “Caucasian blood cannot be mixed with that of any other and survive.” The same article reasserted that the Klan “restrict[s] our organization or those … born of parents who are American citizens [in order to] completely eradicate … any trace of foreign influence.”32 While birth in America technically meant one was an American citizen, it must be remembered that the Klan believed only white Protestants were authentic citizens. The fear of alien influence also helped the Klan cling to ideas of white supremacy. In this way, the Klan built on contemporary fears that immigrants were responsible for the societal problems of the 1920 s and hence banning immigrants was the only way to keep America safe and secure. Klansmen believed that the only way to keep their country as it should be was to keep the white race intact as they were the ones who built America.

Klansmen argued that “the installation of racial equality” would create problems that would destroy America because African Americans and other racial minorities were “ignorant enough to believe” that they were equal to whites and would “consequently attempt to take a place with the white man in social and political affairs.”33 In addition, the Klan believed that the institution of racial equality would allow for intermarriage and the birth of mixed race children, which, the Klan maintained, still did not make a person white and was ‘just another case of camouflage.”34 Klansmen believed that non-white people were and always would be genetically inferior to whites. This was a large part of a Klansmen’s identity.

Aside from personal and historical justifications for white supremacy, the Klan also looked to the Constitution for validation. An account of an initiation ceremony recounts a speaker’s words about what the Klan represents and stands for. According to this account, the Klan “demands the continued supremacy of the white race as the only safeguard of the institutions and civilization of our country.”35

While the Klan opposed people of color already in America, it also sought to keep newcomers out. It demanded that bans and strict regulations be placed on immigration because of the need for a supposedly more united America, which in reality made it more divided. Klansmen were also apprehensive about people coming in and bringing new ideas that they considered un-American. Much of this part of their identity came from the upholding and esteem they placed on the ‘old world.’ They believed that American “civilization must be cleansed and purified from the ground Up”36 and the inclusion of new immigrants would not allow for such cleansing. They saw it as their duty to uphold the values of whites and keep a pure bloodline, which also fueled their fight against immigration. No new people meant no influence or mixing.

The Klan explained its belief in white supremacy as God-given and something in which members should have great pride. One issue of Watcher on the Tower ran a piece titled “Declaration of Principles” in which the Klan affirmed its beliefs about white supremacy. It read:

We believe in the supremacy of the white race, and that it is just and right the younger brothers should be taught to respect those lines of birth and color which the Creator in His superior wisdom has drawn. The white race numbers millions less than the colored peoples of the world and for that one reason, if no other; we believe that the heart of every white man, woman and child should be firmly implanted in an unselfish manner the “Pride of His Race”

The Klan used sources like this to bring others to accept the idea of white supremacy. They even pointed out the possible threat of not forming a solid and united white front. Being outnumbered meant that whites (i.e. “true” Americans) would lose their hold on their country and it would go further into ruin in the hands of non-whites. While this was the only time an actual ratio was used, throughout Watcher on the Tower the Klan identified white supremacy as a way to see America and its people, once again placing themselves in the role of saviors.

Masculinity, Fraternity, and the Klan

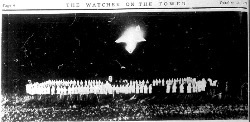

Much of the second Klan was rooted in the idea of what it meant to be manly and belong to an exclusive group of elite members. One of the greatest differences between the first and second Klan was the establishment of the latter as an association with more elaborate rules and rituals as opposed to a less cohesive group of angry southerners. The 1920s Klan in Washington State, like the first formed in Georgia, was not only highly secretive, but also operated on rituals that strengthened a fraternal bond between members. Membership in the Klan gave men a feeling of strength, authority, and belonging. The film Birth of a Nation gave Klansmen a basis to form identities as protectors of women’s purity and innocence, and sought to accomplish this through a “great Brotherhood of Man” and their “glorious American manhood.”37 The fraternal bond members shared was embedded in their purpose for the “defense of the American home” and “stubborn loyalty to the virtue of womanhood and honor among men.”38 In other words, much of the Klan’s identity was centered on older beliefs of a strong patriarchal household in which the man is both the protector and sovereign leader.

In a sample of Watcher in the Tower articles taken from June 1923 to October 1923, there are only four written specifically for or by women. However, gendered rhetoric appears repeatedly throughout the paper in the discussions of Klan principles. Klansmen believed that “women should be respected and protected, and that the purity of the women of the white race is on the great cornerstone in the eternal foundations of [the] great nation.”39 Women were represented as embodying all things good and innocent on Earth and Klansmen looked at their protection symbolically as protecting America. The plot of Birth of a Nation turned on the idea of shielding women from evil - specifically that of a black man attempting to rape a white woman - and so perpetuated the idea of pure and innocent white womanhood.

While public political and social spheres helped to shape Klan identity, the greatest influences took place among members under secrecy. Only in trying to gain support were things that played to masculinity published. For example, the Klan had an internal document entitled “The Practice of Klannishness” that explained how Klansmen were to act. It defined the Klan as “a number of real men, each whom is the embodiment of true American manhood, of kindred purpose, actuated by unselfish motives, dedicated to a manly mission.”40 As this document suggests, Klan rhetoric readily incorporated ideas of manliness and honor, which Klansmen in turn used to define themselves.41

While both versions were the result of changing times and rose in the aftermath of major wars, the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s was vastly different from the one created in the years following the Civil War. This was true on a national level as well as in the state of Washington. Washington’s Klan in the 1920s reveals the ways in which the Klan rallied public support for its program as well as how Klan members thought about themselves. They pushed for “pure Americanism” and the defense of what they considered traditional standards of law, order and social morality.42 Klansmen saw themselves as avengers of an older American way of life in which family and religion were of utmost importance. They were anti-Catholic and strongly opposed immigration, and like the first Klan still clung to the belief in white supremacy. More so than the previous Klan, Watcher on the Tower demonstrates the second Klan’s deep belief and identity of the Klansmen as true Americans. The newspaper revealed to those that read it how the KKK placed itself in the context of the modern world in the 1920s.

At the end of World War I, the Klan gained strength and support, but that did not last long. However, while the second Klan’s popularity was brief, its impact on Washington State and throughout the nation was consequential. While many people will still never hear about the Ku Klux Klan beyond its southern roots, there is an importance to understanding how the Klan was revived and what Klansmen believed they represented. The Klan believed in “100 per cent … white supremacy, man and womanhood, Protestantism and Americanism.”43 Watcher on the Tower sheds light onto this secret society as well as insight into a neglected c

Copyright © Brianne Cook 2007

HSTAA 498 Spring 2008

1 N. S. Sedanthar, “Klansmen make Your Power Felt,” Watcher on the Tower, June 20, 1923, p. 3,.

2 William Loren Katz, The Invisible Empire: The Ku Klux Klan Impact on History (Washington DC: Ethrac Publications Inc, 1986), 64.

3 Katz, 75.

4 Katz, 75-76.

5 Jackson, 4.

6 David M. Chalmers, Hooded Americanism: The First Century of the Ku Klux Klan, 1865- 1965 (Garden City: Doubleday and Company, 1965), 216.

7 Shawn Lay, Invisible Empire in the West: Toward a New Historical Appraisal of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920’s (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 6.

8 S.A.P., “Our Liberties are In Danger: Patriotic Societies can Save us if you will Join Them,” Watcher on the Tower, Oct. 13 1923, p. 7

9 S.A.P., 7.

10 Lay, 7.

11 “The Story of the Klan on the Tennessee,” Watcher on the Tower, July 28, 1923, p. 5

12 “School Books Must be Free of Propaganda,” Watcher on the Tower, July 21, 1923, p. 2

13 Baron Dudley “Protestant Mothers and Fathers, Read These Cautionary Statements and Ponder Well,” Watcher on the Tower, July 21, 1923, p. 2

14 Luther Powell, “The Roman Katholic Kingdom and the Ku Klux Klan,” Watcher on the Tower, August 11, 1923, p. 4

15 S.A.P., 7.

16 H. H. Bower, “Why I am a Klansmen,” Watcher on the Tower, Aug. 4, 1923, p. 2

17 S.A.P., 7.

18 S.A.P., 7.

19 S.A.P., 7.

20 Lay, 20.

21 Special Commissioner, p. 4.

22 Special Commissioner, p. 4.

23 W.F. Phelps, “W.F. Phelps on the Simplified Constitution of the United States,” Watcher on the Tower, Aug. 18, 1923, p. 6

24 Phelps, p. 6.

25 National Headquarters, “Declaration of Principles: National Junior Order Knights of the Invisible Empire,” Watcher on the Tower, Aug. 25, 1923, p. 2

26 O.V. Davis, “What the Klan Does Not Stand For,” Watcher on the Tower, p. 13, Oct. 6, 1923. ~A Davis, “What the Klan Does Not Stand For,” Watcher on the Tower, Oct. 6, 1923, p. 13

27 Davis, p. 13.

28 “Grand Dragon and Great Titians will hold National Conference at Asheville in July,” Watcher on the Tower, July 21, 1923, p. 3

29 Judge John J. Jeffery, “The Klan and the Law,” Watcher on the Tower, Oct. 20, 1923, p. 2

30 Bower, p. 2.

31 Bower, p.2.

32 “National Junior Order Knights of the Ku Klux Klan,” Watcher on the Tower, Aug. 18, 1923, p. 5

33 Davis, p. 13.

34 Davis, p. 13.

35 Special Commissioner, 4.

36 Jeffery, p. 2.

37 “National Junior Order,” p. 5.

38 Rev. Robert Shuler, “The Tidal Wave of Klux ism,” Watcher on the Tower, Sept. 22, 1923, p. 5

39 “National Junior Order,” p. 5.

40 “The Practice of Klanishness,” Imperial Instructions, Document No.1, Series AD. 1924, AK. LVIII. 41 Nancy MacLean, Behind the Mask of Chivalry: The Making of the Second Ku Klux Klan (New York:Oxford University Press, 1994).

42 Lay, 7.

43 Bower, p.2.