Abstract: The Japanese-American Courier was the first Japanese-American newspaper published entirely in English in the United States. A weekly publication serving the Japanese-American community of the greater Seattle area, the Courier was founded in 1928 by James Y. Sakamoto. After establishing a loyal local base, the Courier expanded publication to include the entire West Coast, launching district offices in three California cities while becoming the largest English-language Japanese newspaper in the United States. The newspaper ceased operations on April 24, 1942, just before the U.S. Government forced the entire Japanese-American community into internment camps during World War II.1 This report focuses on the years 1937 to 1940. The Courier was circulated under the banner, “For Truth, Justice and Tolerance”2 and addressed a wide range of local, national, and international topics, including Americanism, national politics, Japanese news, Japanese-American Citizens League (JACL) events, education, and economics. Aimed primarily at an audience of Nisei, or second-generation Japanese-Americans, the Courier also included sports scores, advertisements, occasional classified ads, and more rarely, cartoons.

Dates Published: January 1, 1928 through April 24, 1942. Weekly publication with Saturday distribution along with irregularly distributed “seasonal” issues, including special spring and New Years publications. Five cents per copy, two-dollar annual subscription, two-dollar and fifty-cents annual foreign subscription.

Editors: James Y. Sakamoto (Editor and Publisher), Tadao Kimura (Associate Editor), Tooru Kanazawa (Associate Editor), William Hosokawa (Associate Editor).

Initial Business Office: 317 Maynard Avenue, Seattle, Washington

Subsequent Business Offices: 214 5th Avenue S. Seattle, Washington; 1228 Fourth St. Sacramento, California (Northern California District Office); 728 Collins St. Fresno, California (Central California District Office); 741 N. Boyle Ave. Los Angeles, California (Southern California District Office).

Location of Research Collection: University of Washington, Suzzallo Library, Microforms and Newspaper Collection, A3902

Report

“THE COURIER, established January 1, 1928, shall be published with a close regard to the general principle of Truth, Justice, and Tolerance, for: in the associations between nations as among mankind, truth is the compelling force of justice, the administration of which shall respond to a just call of tolerance. – The Publisher.”3

Just as the Publisher’s statement evokes time-tested values – truth, justice, and tolerance – that are believed by many, an historical examination of The Japanese-American Courier illuminates a time-tested struggle – assimilation into a foreign culture – that was experienced by many. By offering headlines on world, national, and local news, along with sports scores and classified advertisements, the Courier shared many of the common features of any modern newspaper. Yet only in that regard can a comparison be made. Focusing chiefly on the concerns of younger, second-generation Japanese-Americans (Nisei) and seeking to help them make sense of their world, the Courier regularly published articles relating to nationalism, moral obligations, the Japanese-American Citizens League (JACL), and education. Seemingly disparate, these recurring topics coalesced into one larger, overriding theme – what it meant to be Nisei in 1930s America.

The Japanese-American Citizens’ League (JACL)

In 1929, publisher James Sakamoto helped to establish the Japanese American Citizens’ League (JACL). The purpose of the JACL was to facilitate assimilation for second-generation Japanese-Americans while educating the larger public about Japanese-American life. The JACL had modest beginnings but witnessed rapid growth throughout the 1930s. From its first convention in 1930, where eight charter affiliates met at the Seattle Japanese Chamber of Commerce Building, the JACL expanded between 1930 and 1940 to fifty chapters, with nearly six thousand members.5

During its rapid expansion, the league received prominent coverage in Sakamoto’s Seattle-based newspaper, The Japanese-American Courier. Sakamoto believed that “instead of worrying about anti-Japanese activity or legislation, we must exert our efforts to building the abilities and character of the second generation so they will become loyal and useful citizens who, someday, will make their contribution to the greatness of American life.“4 In this way, Sakamoto echoed the JACL’s focus on self-improvement through assimilation rather than outspoken protest.

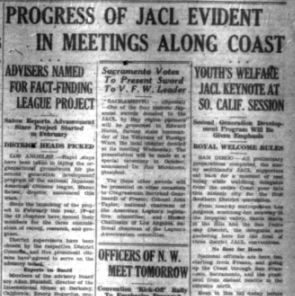

The position of the JACL, as voiced in the _Courier,_sometimes shifted in response to contemporary conditions, but the underlying message of helping Nisei absorb into the fabric of American society remained constant. The JACL’s initial position focused on cultivating American citizenship values as a means of improving the welfare of Nisei youth. An example of this can be found in the July 3, 1937 issue of the Courier. On that date, the paper ran an article headlined, “Progress Of JACL Evident in Meetings Along Coast.” Other articles in the same issue reported, “Advisers Named For Fact-Finding League Project” and “Youth’s Welfare JACL Keynote at So. Calif. Session.”6 Together, these articles comprise a succinct example of how the promotion of Nisei interests was blended with Americanism. According to the articles, the advisors were chosen, “for their deep interest in the second generation, and their experience with and knowledge of the various problems of … Japanese in the United States.”7 The second article states, “Interwoven with holiday gayety … was the more serious aspect of establishing on a firmer basis the furtherance of second generation welfare.”8 The holiday to which the article refers is Independence Day. Thus, while meeting for “second generation welfare,” the JACL was simultaneously celebrating a distinctly American holiday. On another occasion in September of 1937, the JACL held a district meeting in Yakima which “opened with impressive ceremonies in which was featured a flag ceremony by Japanese-American Boy Scouts, the singing of the Star Spangled Banner, and by an invocation.”9 Again, the JACL made celebratory notice of traditional American institutions, in this case the Boy Scouts and the national anthem, with the purpose of combining citizenship values with the development of second-generation Japanese youth. The link between second-generation welfare and American citizenship values was not incidental. Indeed, it was fundamental to how the JACL and the Japanese-American Courier understood their roles in the Japanese-American community.

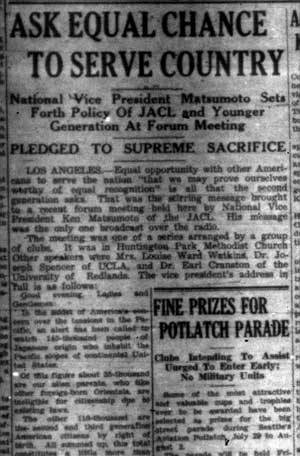

By 1940, the possibility of war with Japan brought a subtle yet perceptible change in the character of the newspaper. The Courier continued to reiterate the JACL’s and the Japanese-American community’s patriotism. Now, however, the previous stress on citizenship values was eclipsed by forthright pledges of fidelity to the nation. In 1939, a Courier sub-headline read, “American Loyalty Stands First.”10 In September of 1940, the Courier proudly exclaimed, “Put us to the test, and we shall prove our metal – as loyal American citizens!”14 And later in 1940, as the threat of war continued to grow, the paper reported the JACL’s decision to pass “Sweeping resolutions reaffirming the League’s allegiance and devotion to the United States, and pledging 100-percent backing for national defense.”12 Youth advancement and citizenship was the foundation for JACL conventions in 1937, yet by 1940, the message had shifted toward staunch Americanism and loyalty. As the mouthpiece of the JACL, Sakamoto’s Courier was responsible for articulating the League’s position to both its Japanese-American readership and the larger public.

Attention to Intolerance

Close attention to the issue of citizenship rights and discrimination was another major aim of articles in the Courier. Historian Quintard Taylor has argued that “the Courier rarely commented on discrimination against blacks and other minorities.”15 While generally true, this does not account for the extent to which the paper did focus on the citizenship rights of “outside groups” other than the Nisei, usually with the purpose of relating those examples directly back to second-generation Japanese. In 1937, a front-page article addressed a District Court verdict involving a Swedish woman of dual citizenship. The opening paragraph hardly mentions any specifics of the case, but states that the Court’s decision, “upholds the principle that any person born under the American flag can never lose his citizenship.”16 Further into the article, the details of the case are treated, but the issue of dual nationality was the primary concern to the readers of the Courier and the reporting reflects as much. Misunderstandings of cultural differences and emphasis on the American melting pot as a “two-way process”13 were also frequently visible on the Courier’s front-page.

Confrontational language was rarely a feature of the Courier’s articles on discrimination. Instead, the _Courier_preferred to quote nationally respected speakers, intellectuals, and educators denouncing prejudice. Quoting a professor of education at New York University, the Courier reported that assimilation “called for efforts on behalf of both the majority and minority groups.”17 University of Washington associate researcher John A. Rademaker was quoted on the front-page of another issue, saying, “Most races have built bridges to their neighbors, bridges which have been strengthened and widened through the adoption of common usages by both peoples, and finally reinforced by the cement and steel of intermarriage, until at last no distinction exists.”18 And in 1940, a front-page article citing two scholars proclaimed, “Real Christianity Bars Intolerance,”20 and contended that true adherence to faith “is the solution of racial intolerance and bigotry.” Thus while it is true that the Courier did not frequently or militantly speak out on issues of racism and discrimination, to suggest that the paper was unconcerned with these issues is not entirely accurate; rather, its goal was to connect the struggles of other groups to Japanese-Americans in ways that would empower the community.

An Eye Toward Education

Quintard Taylor argues that Japanese-Americans sought to “wage their battle for human dignity within the confines of … academic success,”21 rather than political agitation. Indeed, academic achievement was regularly noted in issues of the Courier, particularly in late spring near commencement. In 1938, the Courier front-page proclaimed: “Barely exceeding the 1937 total, some 27 second generation will receive their sheepskins from the University of Washington.”22 The article then proceeded to individually name each graduate. Even high school graduates received front-page coverage. A 1938 article boasted, “With the largest number of second generation ever to be graduated in one year, the high schools of Seattle will hold their commencement.”23 High school students also received individual recognition by name. The placement of these notices on the front-page clearly indicates the importance of education to the Japanese community, yet it also has a larger implication – one of advancement. Each year the _Courier_made note of the rising number of graduates at all levels. This suggests that more than just student graduation was at stake; more importantly, the community was moving forward.

Much like other aspects of the _Courie_r, the language for celebratory experiences such as graduations shifted in the early 1940s in response to the increasing possibility of war with Japan. Many of the articles now employed war metaphors. For example, while displaying an image of Nisei graduating with university honors, a May 1940 article stated, “Facing Life’s Battle Bravely,”24 while another was headlined, “Young Graduates Facing Job With Will To Conquer.”25 The article itself announced a roundtable discussion titled, “After Graduation, What–?” The terminology employed by the Courier, such as “Life’s Battle” and “Will To Conquer,” is suggestive of the climate of rising tension facing Nisei in 1940 and – in keeping with the Courier’s assimilationist message – also implicitly linked young Japanese-Americans with America’s military mission.

Advertising Assimilation

Advertisements in the Courier, both business-related and classified, reflect the tension between cultural insularity on the one hand and a desire for assimilation on the other, present in Seattle’s Japanese-American community. Business advertisements appear in every issue of the Courier. These ads were largely for Asian-named enterprises such as The Gyokko Ken, N.Y.K Japan Mail, Nikko Low, Dr. James Unozawa, Yokohama Specie Bank, and Asahi Garage. The ads highlight the fact that while economic opportunities were available to Japanese-Americans, they were mostly limited to the Japanese community. Of a more suggestive note are the illustrations some of these businesses employed in their advertisements. Almost exclusively, ads depicted Caucasians, even if the stores were owned by Japanese and served a Japanese clientele. Cartoons appeared only in the New Year’s Day edition of the Courier, but these cartoons also featured images of Caucasians, generally of a patriotic character such as Uncle Sam or Lady Liberty. When aggregated, these images and advertisements imply a “selling” of assimilation; in other words, it was permissible to advertise an “American” look, even if the target audience was anything but. The result is a newspaper consciously geared toward Nisei that does not even present illustrations of Nisei.

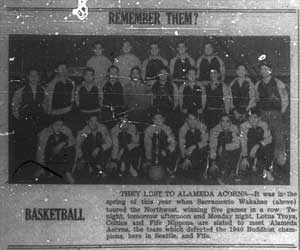

Classified ads were infrequent yet consistently requested the same thing – a domestic servant. On April 13, 1940, five “Wanted” ads ran in the classified section and four requested a domestic servant.29 While this alone gives only fragmentary evidence of the overall economic opportunities available to Nisei, it does aptly portray the opportunities that society at large would willfully offer. The Courier also presented advertisements, both front-page and mid-issue, for the “Courier Radio Program.”30 With a call sign of KXA, and located at 760 on the radio dial, this was a broadcast of Courier-related material and news. Sporting news also received prominent coverage in the Courier, often with one (sometimes more) full-pages devoted to scores. In fact, theCourier actually sponsored many of these sporting events and leagues. A 1938 sports section blurb reminded readers of, “the past nine years of The Courier Basketball league’s existence.”31 Much more than simply a provider of news then, sponsorship of sports teams and the “Courier Radio Program” indicates the extent to which the Courier was a vital community-building institution for Seattle’s Japanese-Americans.

Conclusion

James Sakamoto established The Japanese-American Courier in 1928 and in 1929 was a founding leader in the Japanese-American Citizens League, both of which were driven by a desire to help Nisei understand and assimilate into American culture while maintaining a unique cultural identity – in short, to be Japanese-American. The Courier emphasized larger community values through deliberately aimed news coverage and created a network that included radio broadcasts and sports leagues. To understand the _Courier_and its content is to perceive the difficulties of being an “outside group” in American society. The Courier did not advocate outward confrontation of prejudicial practices, but rather inward cohesion through the development of community. It offered possibility in the face of confusion and hope in the shadow of uncertainty. It proclaimed that truth, justice, and tolerance were its values and that those values would not – indeed could not – lose to ignorance, inequality, and prejudice. It helped expose the Nisei to America and America to the Nisei because assimilation, the Courier argued, was a “two-way street.” The Nisei were not the first travelers along this street and, looking at today’s headlines, they certainly will not be the last.

Copyright © Mark Morzol 2007

HSTAA 353 Spring 2006

Endnotes

-

HistoryLink.Org (2005). File #3352. The Online Encyclopedia of Washington State History. Retrieved May 17, 2006, from http://www.historylink.org/_output.CFM?file_ID=3352

-

Quote located under the newspaper title and above the date on every issue.

-

Quote located on page three of every published issue. “The Publisher” anonymously refers to James Sakamoto, who published the newspaper throughout its existence.

-

Alex Hong, Anson Leong, Jean Wang, Eric Yasui. (1995.) The Japanese-American Citizens League. Santa Clara University. Retrieved May 17, 2006, from http://www.scu.edu/diversity/jaclhis.html

-

Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle, WA: The University of Washington Press. 1994), 120.

-

“Progress of JACL Evident in Meetings Along Coast,” The Japanese-American Courier, July 3, 1937.

-

“Advisers Named For Fact-Finding League Project,” The Japanese-American Courier, July 3, 1937.

-

“Youth’s Welfare JACL Keynote At So. Calif. Session,” The Japanese-American Courier, July 3, 1937.

-

“JACL District Conventions Hit Americanism Keynote,” The Japanese-American Courier, September 11, 1937.

-

“Only JACL Serves All Young People,” The Japanese-American Courier, July 1, 1939.

-

“Realities of Life Face Convention,” The Japanese-American Courier, June 1, 1940.

-

“JACL Confab Puts Americanism First.” The Japanese-American Courier, September 7, 1940.

-

“American Theory of Melting Pot Held Fallacious,” The Japanese-American Courier, November 27, 1937.

-

“Try Us, Uncle Sam, Young Folk Reply,” The Japanese-American Courier, October 19, 1940.

-

Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community, 127.

-

“Native Americans Can’t Lose Rights,” The Japanese-American Courier, November 27, 1937.

-

“American Theory of Melting Pot Held Fallacious,” The Japanese-American Courier, November 27, 1937.

-

“Education Erases Racial Prejudice,” The Japanese-American Courier, October 2, 1937.

-

“Japanese Loyal To U.S., Texans State,” The Japanese-American Courier, October 1, 1938.

-

“Real Christianity Bars Intolerance,” The Japanese-American Courier, November 9, 1940.

-

Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community, 109.

-

“27 Young Slated At Washington U,” The Japanese-American Courier, May 28, 1938.

-

“179 Young, Record For High Schools,” The Japanese-American Courier, May 28, 1938.

-

“Facing Life’s Battle Bravely,” The Japanese-American Courier, May 25, 1940.

-

“Young Graduates Facing Job With Will To Conquer,” The Japanese-American Courier, May 25, 1940.

-

“First Japanese Deputy Is Named In Pierce County,” The Japanese-American Courier, December 18, 1937.

-

“Lone Japanese Girl To Receive Diploma,” The Japanese-American Courier, December 11, 1937.

-

“Scientist Finds Japanese Change In This Country,” The Japanese-American Courier, August 27, 1938.

-

Listings of classified ads, The Japanese-American Courier, April 13, 1940.

-

Advertisements, The Japanese-American Courier, December 25, 1937.

-

“Basketball Reports,” The Japanese-American Courier, January 22, 1938.