Abstract: “A Newspaper the People Read, Love & Respect:” this slogan boldly declared the Northwest Enterprise’s importance in Seattle’s African American community on the front page of every issue. The _Enterprise_was, as Quintard Taylor writes, “the most widely known Seattle black business, and arguably the most successful.”1 Published from 1920 through 1952, the paper circulated throughout the Pacific Northwest and had readers in Oregon, Idaho, and Montana, in addition to Washington State.

Wiliam H. Wilson founded the NW Enterprise in 1920 and edited the weekly until 1935.2 Under his guidance the newspaper was a strong voice for the African American community and for broader issues of racial justice. An early leader of the NAACP, Wilson and his newspaper attacked segregation and led campaigns against police brutality. The paper retained its activist tone under the sequence of editors who managed it in the late 1930s. In 1939, drug store owner Edward I. Robinson purchased the Enterprise. Under his leadership, the paper achieved one of its proudest moments in 1942 when it led the successful campaign to force Boeing to begin hiring African Americans.3 This report examines the newspaper a few year later, during the early Cold War.

For the entire three-year span examined here, 1947-1949, the editor and publisher was E.I. Robinson. Consequently, the overall tone and style of the paper remained fairly consistent throughout the period. It was published weekly, usually on a Wednesday, and consisted of 5-7 pages of world, national, and local news targeted at a middle-class African American audience, as well as editorials, social and church related events, and advertisements for local businesses. The Northwest Enterprise, at least in the late 1940s, tended to take a relatively conservative position, particularly when it came to issues of religion, business and labor, politics, and social norms. However, the newspaper’s opportunistic stance towards, for example, national political parties, indicates that in Seattle the black community’s allegiance was first and foremost to whatever or whomever was perceived to further ‘the negro race.’ The topics the paper covered, the tone of the editorials, and even the advertisements all provide clues as to what the black community of Seattle was concerned with, proud of, and purchasing in the post-World War II economic boom.

Churches

The significance of the church as a social, cultural, and even political institution in black Seattle is readily apparent in the unapologetic religious content of _The Northwest Enterpris_e. There is, almost without exception, not a single issue from 1947 to 1949 that did not feature some article on Christian morals or customs, or exhort its readers to attend church, or church-related functions. In fact, there was a section on the second page of every issue that listed the various African American churches in Seattle, along with locations and times of services. Church-related events, such as conferences and leadership conventions, were also covered in detail, and in 1947 there was a short-lived feature in which a sermon was reprinted for “shut-ins.”4

Religion as the antidote to, and enemy of, communism was an important theme. As declared in the paper on May 4, 1948, religion was “the only hope for the future in the atomic age.”5 And, on January 28, 1948, communists are “the sworn enemies of Christian civilization.”6

However, the church was much more to the black community than simply a safeguard against threatening political radicalism. It was truly the cornerstone of the black community in Seattle, providing not only spiritual guidance, but also welcoming the city’s new black residents, of which there were many after the war, and hosting social events such as picnics, dances, and clubs.7 Churches were some of the oldest black institutions in Seattle, so, in a sense, it is not surprising that the paper assumed its readers were churchgoers. This assumption was even more prevalent on religious holidays, particularly Easter and Christmas. Each year, as Christmas Day approached, the amount of ‘hard news’ decreased and the paper was increasingly devoted to religious stories and songs, holiday greetings from prominent members of the community, Bible verses, and invitations to seasonal events. In its 1948 Easter issue, for example, the Northwest Enterprise published a description of Jesus on the front-page alongside its more traditional political news.

Religion was also portrayed as the enemy of, and antidote for, communism. As the paper declared on May 4, 1948, religion was “the only hope for the future in the atomic age.”8 And on January 28, 1948, Communists were called “the sworn enemies of Christian civilization.”9 Although the church represented much more to the black community than simply a safeguard against the threat of political radicalism, the linkage of Christianity with anticommunism in the Northwest Enterprise does suggests the important political function fulfilled by the church in Seattle’s African American community.

The overall theme of Christianity being the only acceptable religion, as well as the de facto segregation of churches in the city, appears to have weakened by 1949. In this year there were glowing articles about interfaith conferences and interracial youth groups, such as choirs. The paper may have been grounded in the Christian religion, but its depiction of what Christianity looks like was by no means constant.

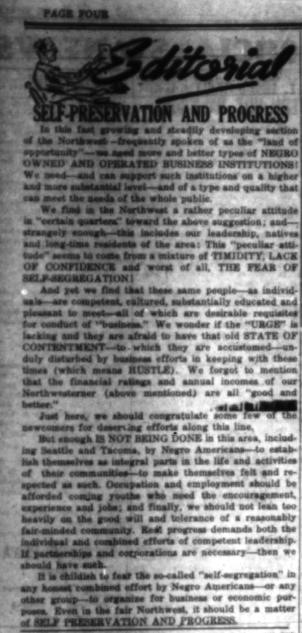

Business and Labor

The Northwest Enterprise devoted extensive coverage to the relationship between business and labor in the post-World War II period. Reflecting the paper’s conservative tilt, most of the articles featuring labor-related issues focused less on the plight of black workers, or of all workers for that matter, than on the effect of laws and union policies on the success of individual businesses or on capitalism in general. For example, in the September 17, 1947 issue there was an article entitled “Do You Know?” which explained in detail how the anti-labor Taft-Hartley Act (1947) actually protected workers from power-hungry unions.10 On April 7, 1948, the United Mine Workers Union (UMW) was described as a “one man union,”11 and the article posited that miners were not underpaid and that a work stoppage would be “the worst thing for America.”12 In a similarly conservative vein, a December 10, 1947 opinion piece offered advice on “integrating the negro worker”13which put the onus on African Americans to “put up with embarrassment”14 on the job in order to ensure a smooth transition into a desegregated workplace. And in September of 1947, a prominent local black businessman and frequent contributor to the Northwest Enterprise, Prentis L. Frazier, wrote an article, which the paper featured on the front-page, discussing how “‘negroes bad behavior … blacks out a fine racial record.”15

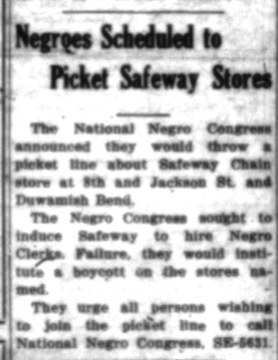

While the prevailing message during these years came from the conservative voices of Seattle’s business community, the Enterprise demonstrated its heterogeneity in its September 17, 1947 issue – the same issue that featured the anti-union piece on the Taft-Hartley Act – by publishing a pro-union article exhorting the need for “national solidarity”16 and union unity. Moreover, when it came to injustices directed specifically at black workers, the paper was much more willing to criticize business on behalf of labor. For instance, on June 11, 1947 the paper called on readers to picket Safeway stores for their refusal to hire blacks.17 And on March 9, 1949, a triumphant front-page headline read “FEPC Bill Passes Legislature.18 Thus, though the Northwest Enterprise may have had diverse views on labor and business, on the subject of equal rights for African Americans there seems to have been unity.

Politics

The political coverage in The Northwest Enterprise from 1947 through 1949 was dominated by one overarching theme: the perceived threat of communism. “This is America” cartoons were common in 1947 and 1948 issues of the paper. The cartoons depicted ‘facts’ of American ingenuity and capitalist individualism being rewarded throughout history. A frequent contributor of op-ed style pieces, Ruth Taylor, wrote that “[Christianity is] the only faith behind democracy.”19 And on January 28, 1948, another article evoked fear of “the sworn enemies of Christian civilization- the communist [sic].”20 A September 15, 1948 editorial, “The Challenge,” stated, “We are living in epic times. We are challenged by the menace of Communism. … We spent billions to stem the tide or surrender to Communism in Europe and tolerate its conspiracy at our very doors.”21 On November 3, 1948, another editorial argued that “by contrast with the crimes of Communists, all other crimes are trivial,”22 while a headline in the same issue proudly proclaimed “US No Sanctuary For Communists.”23

The onslaught of pro-capitalist material in the paper was augmented with coverage of local, national, and even global politics, and especially stories of successful African Americans, such as black college graduates, athletes, actors and musicians, and blacks gaining prominent positions in universities, businesses, and the government. Articles on Jim Crow laws in the South and violence against blacks across the country were, regrettably, about as frequent as the success stories. On December 31, 1947, a headline announced, “South Wants No Aid Minus Segregation,”24 and on December 10, 1947 the _Enterprise_reported black churches and a school being “put to torch”25 in Loganville, Georgia.

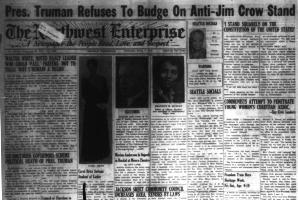

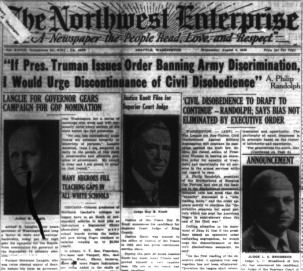

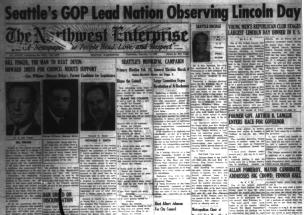

The paper’s coverage of national party politics reflected its ability to shift support to wherever it felt African Americans would gain the greatest advantage. From 1947 to 1949, the Enterprise gradually moved away from portraying the Republican Party in a consistently better light and toward advocating black support for President Truman and the Democratic Party. For example, a February 19, 1947 headline proclaimed “Seattle GOP Lead Nation in Observing Lincoln Day,”26 while in the same issue another headline condemned the “Southern Democrats [who] Threaten Secession.”27 The tide of party allegiance began to turn in 1948 after “Truman Refuses to Budge on Anti-Jim Crow Stand.”28 Support for the Grand Old Party weakened further in June 1948 when there were “no blacks as GOP platform candidates.”29 Truman’s stance on civil rights was analysed in a succession of August, 1948 issues,30 and when the Democratic president was reelected in November, the Enterprise proudly proclaimed “Nation Wide Returns Show Negroes Gave Aid to Truman, Swept in Negro Democrats.”31

Society/Popular Culture

Much like other sections of the paper, the various advertisements and human interest articles appearing in the Ladies Page, Amusements, and Sports sections of The Northwest Enterprise from 1947 to 1949 reveal a great deal about Seattle’s African American community. And again, much of the content reflected the middle-class, conservative thrust of the newspaper. The sections contained numerous articles telling of important social functions, such as weddings, concerts, sporting events, and parties,32 and help document the dense network of social and cultural institutions that Seattle’s African American community had developed by the late 1940s.

There were also some very suggestive articles about the attractiveness of light skin, particularly for black women. A June 11, 1947 article headlined “Negroes Vanishing From US”33 claimed that the gradual lightening of African Americans’ skin would lead to a solution to the race problem in American society. Another article in February of 1948, entitled “Black Babies,”34 attempted to use scientific evidence to alleviate fears of dark-skinned children resulting from light-skinned unions, apparently a commonly-held belief at the time. Advertisements for skin-lightening products for women appeared in practically every issue of the newspaper. One particularly blatant ad, featured repeatedly, informs the reader thusly: “Wife Lightens Skin- Wins Back Husband.”35

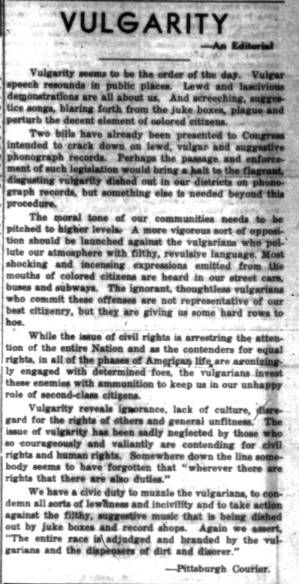

Several other opinion pieces stressed that good conduct on the part of blacks was essential to harmonious race relations. A March 17, 1948 opinion piece entitled “Vulgarity”36 stated that “the entire race is adjudged and branded by the vulgarians and dispensers of dirt and disorer [sic],”37 and goes on to ask those “dispensers of dirt” to change their behaviour without questioning the legitimacy of whites judging of an entire race by the conduct of a few of its members. Another opinion piece, this one a letter from Mrs. Mildred Rowland of Atlantic City printed on May 12, 1948, was entitled “Good Conduct.”38 Mrs. Rowland provided a list of tips for blacks that she believed would improve their treatment by whites, including “speak softly,” “don’t make an effort to sit next to other blacks [at a mixed social function],” and “observe all rules” – hardly a recipe for civil disobedience. The paper’s overall sense of conservatism was especially evident on the ‘Ladies Page,’ as evidenced by the advertisements for skin lighteners, and unlike the paper’s positions on business and labor, there were no alternate views presented, nor was there a gradual shift in the treatment of these subjects, as was the case with religion and politics. Relatively unusual for The Northwest Enterprise, it seems that social norms in black Seattle were not only widely agreed upon, but also portrayed unchangingly in the paper from 1947-1949.

The Northwest Enterprise provides a telling glimpse into an ethnic community at a particular moment in history, a moment when Seattle, the nation, and the world were undergoing great change. A close examination of the Enterprise at the end of the 1940s reveals a community deeply concerned with the issues of the nation and the world, but also very grounded in and committed to what was happening at the local level. The newspaper chronicled a community on the cusp of a new decade, one that would bring even greater economic stability and global prominence to the United States, and of a new era that would bring new rights and privileges to black people across the nation. As they prepared to usher in that new era, black Seattle was looking outward, with great hope in a prosperous, democratic future; and black Seattle was also looking inward, attempting to use the principles of Christian morality, American individualism, and black solidarity to make their community the best it could be. _The Northwest Enterprise_shows present day readers that black Seattle was a unique community, not just different from other ethnic groups in the city, but from other black communities throughout the nation. And while remaining a close-knit community bound by the ties of church, business, shared political goals and social norms, black Seattle was in itself diverse and vibrant, with many different voices emerging even in the relatively short period from 1947 to 1949.copyright © Grace Taylor 2007

HSTAA 353 Spring 2006

1.Quintard Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community: Seattle’s Central District from 1870 through the Civil Rights Era (Seattle, 1994), 72.

2 Gerald J. Baldasty and Mark E. LaPointe, “The Press and the African American Community: The Role of the Northwest Enterprise in the 1930s” Pacific Northwest Quarterly (Winter 2002⁄2003), 14-26.

3 Sarah Miner, “Battle at Boeing: African Americans and the Campaign for Jobs 1939-1942,” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project.

4. The Northwest Enterprise. 1947.

5. Anonymous editorial, The Northwest Enterprise. May 5, 1948.

6. Anonymous editorial, _The Northwest Enterprise._January 28, 1948.

7. Taylor, The Forging of a Black Community, 138.

8. Anonymous editorial, The Northwest Enterprise. May 5, 1948.

9. Anonymous editorial, _The Northwest Enterprise._January 28, 1948.

10. “Do You Know?” The Northwest Enterprise. September 24, 1947.

11. Anonymous article, The Northwest Enterprise. April 7, 1948.

12.Ibid.

13. Anonymous article, The Northwest Enterprise. December 10, 1947.

14. Ibid.

15. Prentis L. Frazier, The Northwest Enterprise. September 24, 1947.

16. Anonymous article, The Northwest Enterprise. September 17, 1947.

17.Anonymous article, The Northwest Enterprise. June 11, 1947.

18. Front-page headline, The Northwest Enterprise. March 9, 1949.

19. Ruth Taylor, The Northwest Enterprise. November 26, 1947.

20. Anonymous article, The Northwest Enterprise. January 28, 1948.

21. “The Challenge.” The Northwest Enterprise. September 15, 1948.

22. Anonymous editorial, The Northwest Enterprise. November 3, 1948.

23. “US No Sanctuary For Communists.” The Northwest Enterprise. November 3, 1948.

24. “South Wants No Aid Minus Segregation.” The Northwest Enterprise. December 31, 1947.

25. Anonymous article, The Northwest Enterprise. December 9, 1947.

24.“Seattle GOP Lead Nation in Observing Lincoln Day.”The Northwest Enterprise. February 19, 1947.

27. “Southern Democrats Threaten Secession.” The Northwest Enterprise. February 19, 1947.

28. “Truman Refuses to Budge on Anti-Jim Crow Stand.” The Northwest Enterprise. March 17, 1948.

29. Anonymous article, The Northwest Enterprise. June 9, 1948.

30. Advertisement, Republican Rally. The Northwest Enterprise. October 27, 1948.

31. “Nation Wide Returns Show Negroes Gave Aid to Truman, Swept in Negro Democrats.” The Northwest Enterprise. November 17, 1948.

32.The Northwest Enterprise. May 26, 1948.

33. “Negroes Vanishing From US.” The Northwest Enterprise. June 11, 1947.

34. “Black Babies.” The Northwest Enterprise. February 11, 1948.

35. Advertisement, Dr. Fred Palmer’s Skin Lightener. The Northwest Enterprise. April 14, 1948.

36. “Vulgarity.” The Northwest Enterprise. March 3, 1948.

37. Ibid.

38. “Good Conduct.” Letter from Mrs. Mildred Rowland reprinted in The Northwest Enterprise. May 12, 1948.

--April%2013,%201933--p.1-300.jpg)