The Washington State Rainbow Coalition (WSRC) was a prominent progressive organization founded by activists inspired by African American leader Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign.[1] Based in Seattle and later extending throughout the state, the Coalition sought to create a progressive, multiracial, multiethnic coalition that represented every stripe of the rainbow, or every group in America that was excluded by white male mainstream electoral politics. Active throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, the WSRC took part in nearly every major social movement of the era and contributed to many local progressive victories, though not without occasional tension with the national Rainbow Coalition.

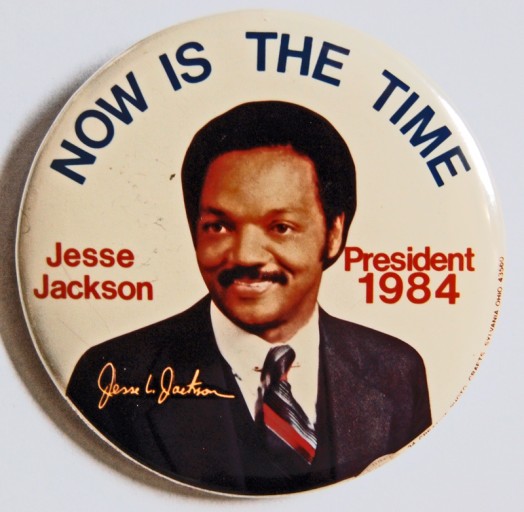

Patterned after a similar coalition founded by the Black Panther Party’s Fred Hampton in Chicago in 1969, Jesse Jackson envisioned that his Rainbow Coalition would establish multicultural solidarity in America. Aspiring to become the first African-American president, Jackson emphasized multicultural grassroots activism in order to appeal to more than just Black voters. As Vernon Damani Johnson, a leader of the WSRC, recalled, “We worked on everybody’s issues. Farm worker issues, immigrant rights issues for both Latinos and Asians, civil rights, voting rights, which affects everybody… labor issues and union issues… women’s equality… [and] LGBTQ organizing.”[2]

Early Years

Although the WSRC was officially founded in 1989, the group had used the WSRC name since 1984 to represent the movement led by Jesse Jackson that they sought to follow. Larry Gossett, a prominent activist in Seattle’s Black community, remembered receiving a call from the Reverend Samuel McKinney, pastor of the city’s Mount Zion Baptist Church, about the WSRC in 1983. Mckinney had “just gotten a call from Jesse Louis Jackson,” Gossett recalled, “and Jesse wanted to organize a political vehicle through which he could run for President of the United States of America, and he definitely wanted a chapter in Washington state.” In addition to Gossett, McKinney reached out to a variety of multiracial activists, pastors, and organizations, and in November of 1983, a group of Seattle activists including Filipina-American organizer Cindy Domingo, El Centro de La Raza Director Roberto Maestas, and Chinese American activist Doug Chan joined Gossett and McKinney to prepare for the fall election season of 1984.[3]

The organization's activities in that year consisted of registering voters in the Central Area, Seattle’s historically Black neighborhood. The Rev. Samuel McKinney spoke to the Seattle Daily Times as the co-chairman of the organization about “plans to register 3,000 new voters… by the Oct. 6 deadline.”[4] Jeri Ware and Juan Bocanegra, local activists and members of the Coalition’s steering committee, spoke about future plans to educate people about local social issues after the election, including future campaigns to defeat anti-abortion and anti-indigenous initiatives.[5] After the elections of 1984, in which Jackson did not win but secured a notable percentage of the Democratic vote in the state, Jackson asked the WSRC to continue organizing, noting the group's success in achieving his vision of a multiracial coalition compared to other chapters across the country.

Between Jesse Jackson’s first presidential campaign in 1984 and his second in 1988, the WSRC remained active and continued to expand. The WSRC took part in a coalition of Seattle groups protesting apartheid in South Africa and efforts to defend abortion.[6] In 1987, Rev. Samuel McKinney, speaking as head of the WSRC, called for an end to U.S. intervention in Central America.[7] As Jesse Jackson’s second presidential campaign in 1988 approached, WSRC efforts increased as activists across the state worked hard in order to achieve a higher turnout than 1984 for Jackson. These efforts proved to be effective, as Jesse Jackson garnered 37% of the Democratic Party vote in March of 1988, an impressive feat for a state with a Black population of about 3% in 1990.[8]

Founding of the WSRC

Following the campaign, the WSRC’s work continued, with plans to hold a founding convention and then apply for state chapter status with the National Rainbow Coalition (NRC). The effort was not without its difficulties. Twice, the NRC urged the WSRC to postpone its founding convention. Initially set for 1988, the founding convention was then held February 10-11 in 1989, despite a second request from the NRC that the convention be postponed further.[9]

This decision was opposed by some the WSRC, namely Roberto Maestas, a founder of Seattle’s Chicano community center El Centro de la Raza, who wished to follow the suggestions of the NRC. This conflict led Maestas and El Centro de la Raza to leave the WSRC and not attend the founding convention. Maestas then spoke to the press about the conflict, claiming to represent the real Rainbow Coalition due to his closer connections with Jesse Jackson and the NRC. Helena Stephens, local activist and member of the WSRC, remembered the split. “The information… got into the newspaper,” Stephens explained. ”And so it got negative publicity, because [before] we had always come across as very united… The press was like, well, which Rainbow Coalition do I talk to? You know you have 2 of them. That got back to Jesse Jackson and Jesse Jackson came out here and said, ‘Clean that up’… And I think that put a bad taste in a lot of people's mouths. And so it was really hard to have that sense of unity. After that it was difficult… We continued on, but it did set us back.”[10] By losing a prominent figure in the community, the coalition suffered.

Regardless, the convention went on as planned in February 1989. Much of the event’s two days were spent discussing the organizational structure of the WSRC and its organizational by-laws. The by-laws that were ultimately adopted pledged the WSRC to being as democratic as possible and fostering grassroots organizing at local levels within the state. It was common knowledge in preparations for the convention that the NRC was possibly restructuring its own by-laws, to which the WSRC might have to adjust in order to become an official state chapter of the NRC. The founding convention also saw its eight officers be elected, four men and four women. True to the multiracial vision of the Rainbow Coalition, four were Black, two were white, one was Native American, and one was Filipina-American.[11]

Expanding Statewide

Following the convention, the membership of the Washington State Rainbow Coalition grew from around 600 people to approximately 900. In the process, the Rainbow Coalition’s presence spread beyond the Seattle-Tacoma metropolitan area to Olympia, Yakima, Spokane, Vancouver, Bellingham, Everett, and Bellevue. To maximize grassroots mobilizations throughout the state, the WSRC operated under a local-unit system, or chapter system.[12] Representatives from each chapter would come together quarterly in committee meetings to go over local topics for support and make decisions for the state as democratically as possible. Meanwhile, Rainbow News, a regular newsletter, meanwhile, kept members informed of what each chapter was up to.

Rainbow News captured what the local Washington chapters worked on and accomplished throughout the years. The February/March issue of 1990, for instance,highlighted crucial political races, food collection for winter shelters, campaigns to keep toxic wastes out of counties, phone banking, wildlife recreation coalitions and newly established youth and family services, protests, new local documentary films, and statewide committees on child-labor standards. Individual chapters also had newsletters. Whatcom County Rainbow Coalition’s Rainbow Record, for example, reported in the Spring of 1990 on the local chapter’s “Housing Strategies for Bellingham” Task Force report to tackle housing scarcity in the community, protests and education surrounding US policy in El Salvador and Central America, support for the statehood of Washington, D.C., and more.[13]

The newsletters also featured the activities and accomplishments of individual Rainbow members throughout Washington state and internationally.[14] A report by Nancy San Carlos in Rainbow News in the winter of 1991 shared about the influential participation of Rainbow co-chairs in the June 1990 State Democratic Convention. Carlos also wrote about state Co-Chair Odette Polintan-Taverna representing Rainbow at a May 1991 conference on Malcolm X held in Havana, Cuba; co-chair Imogene Bowen attending the Fifth International Peace Education Conference in August, 1991 in Zanka, Hungary; Rev. Sam McKinney in a group of ministers invited to visit South Africa; and Co-Chair Thomas Villaneuava’s efforts to improve farm worker conditions.[15]

Tensions with the NRC and 1990 Retreat

Despite the growth of the Rainbow Coalition in Washington, tensions with the NRC continued. In the month following the WSRC’s founding convention, Dave Jette, an activist and member, traveled to a NRC meeting in Chicago as a representative of the WSRC. Upon his return, he reported that the NRC was undergoing a restructuring process, one that appointed Jesse Jackson as the leader and made decisions in a top-down fashion. This new Rainbow Coalition would focus its strategy primarily inside the Democratic Party. For some in Washington state, this seemed antithetical to what the WSRC decided on during its founding convention, which was to focus on local and grassroots organizing, decisions being made democratically, and implementation of a strategy that worked both inside and outside of the Democratic Party. WSRC members were therefore struck with the challenge of trying to be as close to the NRC as possible while also retaining its core values. Phil Berano, a member of the WSRC, recalled this challenge. “Things started to change at the national level after ‘88,” Berano remembered. “That made it more challenging for us to… continue to do our work here in the State of Washington.”[16]

That year, the WSRC failed to become an official chapter of the NRC, and communication between the WSRC and the NRC increasingly became a contentious issue. These flaws prompted WSRC members to start planning a retreat to discuss how to adjust to the NRC’s by-laws, how to foster more communication between the NRC and WSRC, and between local chapters in the WSRC, and to discuss the relationship the WSRC had with other organizations such as El Centro de la Raza. The idea of a retreat appealed to many people in the WSRC and it was decided that it would be held on March 17-18, 1990[17].

In preparation for the retreat, WSRC members thought about where they wanted to see the WSRC in the future. They considered the success of an “inside-outside” strategy within the Democratic Party and how to navigate the electoral arena, and weighed the options for an independent party, local organizing, and lobbying. They set goals, including voter turnout and increased influence within the Democratic Party, as well as increasing the membership of the WSRC and the number of organizations the WSRC affiliated with.[18] These questions informed the WSRC retreat agenda, which included a dozen workshops on a range of topics, from the work of local chapters, to the relationship with the NRC, El Centro de la Raza, and between the leadership and committees.

For many, this was draining work, and some people decided the WSRC was no longer a place they wanted to organize in as they felt that the Coalition was interfering with their grassroots organizing. For instance, Sylvia Smith, a prominent leader in the Thurston County Rainbow Coalition (TCRC), wrote a letter to the WSRC addressing concerns over the TCRC allegedly leaving the WSRC. In this letter, she cited the WSRC focusing too much on power and not enough on fixing problems within the coalition as reasons for the TCRC’s frustration with the WSRC. “Having people give time and energy to come to state meetings all the time is a waste of time and energy that could be more rewardingly spent at the local level,” Smith wrote. [19] She continued by offering suggestions that would better foster grassroots organizing. “While the state structure declines,” Smith concluded, “here in Thurston County we are gaining support daily… Our annual meeting… was a great success… Thurston County has not ‘dropped out.’ We just stopped paying attention to you.” The TCRC, along with other local chapters, continued to find success in their community, some outliving the WSRC after its last meeting in 1996.

Electoral Success

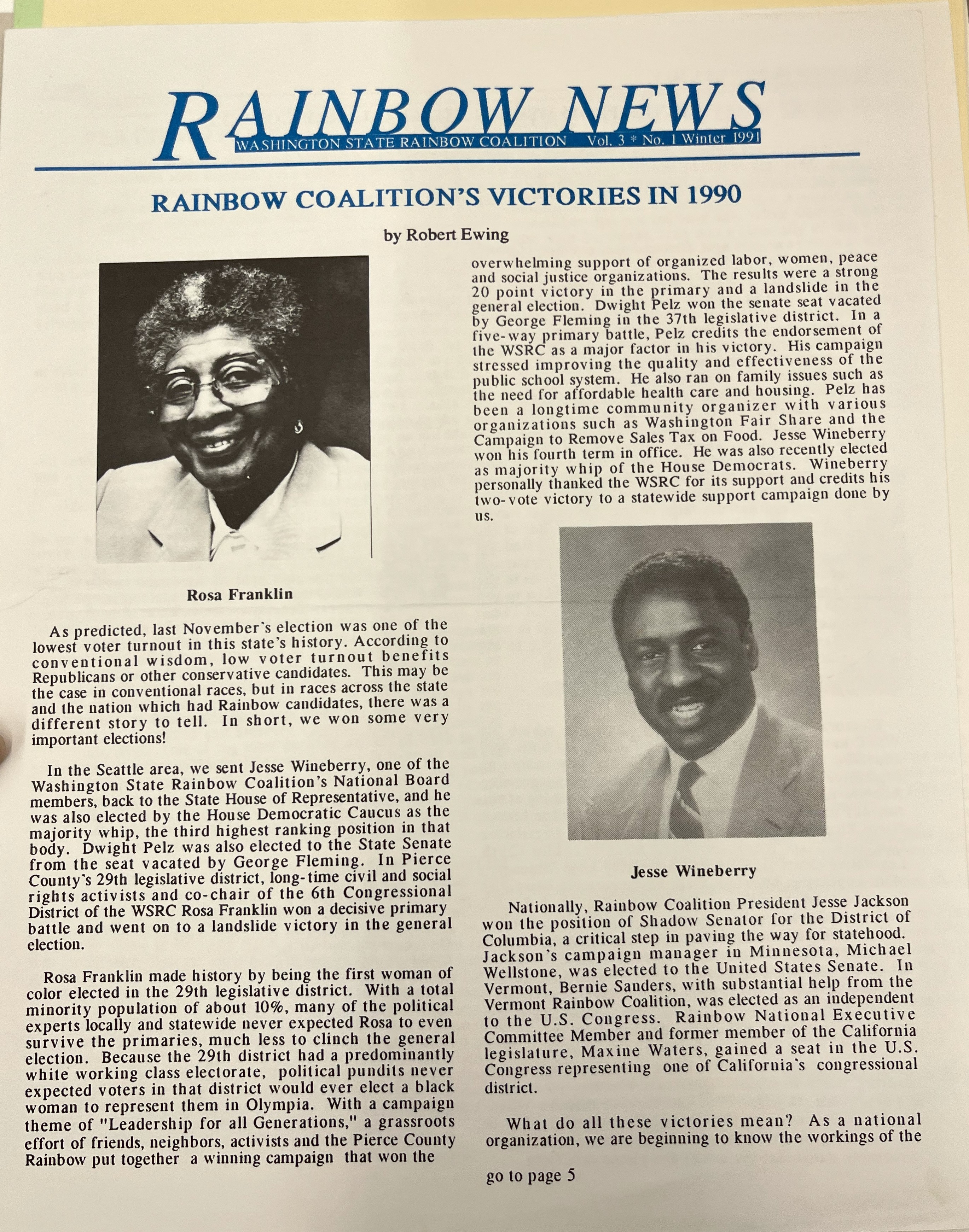

The retreat had mixed success with fixing the problems within the Coalition. For some, the conclusion of the retreat garnered a negative reaction. For instance, in the Winter 1991 Rainbow News WSRC President Gossett addressed a letter written by David Jette called “The Rise and Fall of the Washington State Rainbow Coalition,” which claimed that the WSRC no longer existed. This, of course, was not true, and Gossett’s letter directly disproved Jette’s claim by summarizing the success of the WSRC over the past two years since its official founding. Despite earlier issues with the structure of the WSRC, Gossett noted that the Coalition continued to find success and strong influence over electoral politics and maintained presence in international solidarity struggles and other community issues. “Electoral politics has been a key arena in which the WSRC has began to establish its influence,” he wrote. “In both 1989 and 1990, the WSRC filled many of the key campaign committee leadership positions which helped progressive rainbow candidates win office… in races such as Seattle Mayor Norm Rice, State Senator Dwight Pelz (37th legislative district), State representative Rosa Franklin (29th Legislative District), State Representative Jesse Wineberry (43rd Legislative District), State representative Margarita Prentice (11th Legislative District) and Renton School Board members Nemesio Domingo, Jr. and Brian Smith… Our influence within the democratic party continues to grow and, at last count, we hold leadership positions within the democratic party in 19 legislative districts.”[20] In 1990, for example, Rosa Franklin became the first woman of color elected in the 29th Legislative District, a predominantly white working class district.[21]

In electoral politics, Gossett argued, approval by the WSRC had tremendous power and was constantly seeked out by candidates running for office, and was credited for the victories of key campaigns such as that of Jesse Wineberry winning his fourth term in office and majority whip of the House Democrats in the state legislature.[22] Gossett continued in his letter to talk about the various community issues the WSRC was involved in, writing “The crisis in the Middle East has moved to the top of the WSRC’s agenda. In… December… We voted to become a member of the Seattle coalition for peace in the middle east. The WSRC was also well represented in the huge… December 1st rally held in Seattle… On behalf of the WSRC, I spoke in opposition to war and stressed the importance of our national politicians to declare war on poverty and racism in the U.S., not on the people in the Middle East. Other issues which we continue to actively participate in include: quality education, gay/lesbian rights, AIDS, anti-drug and gang intervention, farm workers’ rights, opposition to the dumping of toxic wastes, and international solidarity struggles.”[23]

End of the WSRC

While the WSRC’s organizing continued across the state, by 1995 it was apparent that the issues within the WSRC had not been fully resolved, leading to the organization’s steady decline. Thaddeus H. Spartlen, in an article for the 1995 winter/fall edition of Rainbow Rap reported, “We have a crisis in member interest and support – poorly attended meetings; officials of the organization who are not fully-paid, current members; and chapters in name which do not meet criteria set forth in our by-laws and in which few are actively doing Rainbow work. Even the length of this newsletter is indicative of financial need, if not crisis.”[24]

The difficulties led to the resignation of WSRC President Imogene Bowen on October 25, 1995. Her resignation letter cited her objection to opinions and votes by members and the Executive Committee on topics including the WSRC’s relationship to a possible Independent Party, Rainbow’s position on controversies surrounding Washington state Governor Mike Lowry and allegations of sexual harassment, and more.[25] A tribal leader and activist from the Upper Skagit Tribe who was widely respected across the state, Bowen’s decision had an enormous impact on the coalition as those in agreement with her views left with her. Helena Stephens, member of the WSRC, recalled that moment. “She was a solid leader, she was rational, and gave good advice and good directions,” Stephens remembered. “It was an emotional blow, because people looked up to her and wanted her advice and her wisdom on things… She was also taking a large group of rainbow supporters with her. So there were a lot of people that were like, ‘If Imogene’s not gonna be here. I'm not gonna be here either.’ And so we lost that stripe of the rainbow. And that was hard.”

Though there were efforts to reorganize the structure of the WSRC to once again provide local chapters with more strength, membership continued to decline throughout the state. Few WSRC records are present from the year 1996, suggesting that the last meeting of the WSRC was in that year. When asked about the end of the WSRC, member Bob Barnes stated, “The organization just sort of collapsed. I think there was an acknowledgement that… We have our monthly meetings, and fewer and fewer people would show up. And we just stopped having meetings. It was kind of pathetic in retrospect.”[26]

The Legacy of the WSRC

However disheartening its final years may have been, the WSRC’s legacy proved real. In many cases, the work of the Rainbow continued independent of the Coalition itself, an indication of the organization’s success. WSRC leader Larry Gossett, for instance, became a longstanding member of the King County Council, serving from 1993 to 2019, implementing Rainbow ideologies into his work as an elected official. Groundwork laid by the WSRC also proved critical to a statewide boycott effort in support of farm workers at the giant Chateau Ste. Michelle Winery in Eastern Washington, who successfully unionized in 1995 after an eight year struggle.[27] Vernon Damani Johnsen remembered, “Some of us said, ‘Let’s start supporting them in their efforts to unionize…” We started to do information pickets at grocery stores… Then we did a publicity campaign around it… And that sped up the process.” And local chapters continued to be powerful forces. The Whatcom County Rainbow Coalition (WCRC) was one of the many chapters that continued to meet up until the 2000s.[28]

In organizing spaces, disagreements are natural and bound to happen. In the WSRC, the strategy of working inside the Democratic Party along with outside of it held great synergy, and the influence of the WSRC on electoral politics and movements within Washington state was strong. Jesse Jackson’s vision for a multiracial, multiethnic coalition ultimately united progressives across the state to work together for a better world across historically marginalized communities. The WSRC proved that multiracial organizing was possible. It also showed the state that minorities were willing to fight for justice and that progressive politics were possible. The WSRC proved to many people that minorities could achieve positions of power, such as Larry Gossett, who did not believe that it was possible prior to the WSRC. Indeed, Gossett and many other former WSRC members never stopped implementing Rainbow principles into the work they continued to do after the WSRC ended. Its history contains important lessons for us today.

[1] Dave Jette, “The Development of the WSRC,” NCIPA Discussion Bulletin no. 2 (Spring 1989), 24, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 8, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1991, Accession No. 5799-001, Special Collections, University of Washington Libraries, Seattle.

[2] Vernon Damani Johnson, interview by Saul Gonzalez, June 12, 2024, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Oral History Project, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington, Seattle. https://archive.org/details/DamaniJohnsonVernon_WSRCOHP

[3] Larry Gossett, , interview by Saul Gonzalez, May 24, 2024, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Oral History Project, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington, Seattle. https://archive.org/details/GossettLarry_WSRCOHP

[4] Dick Clever, “Voter Registrations Set in Central Area,” Seattle Daily Times, evening final ed., September 18, 1984, 16.

[5] Ibid.

[6] “Civil Disobedience planned in protest against South Africa,” Seattle Daily Times, December 3, 1984, 3; “Marchers defend legal abortions,” Seattle Daily Times, March 23, 1986, 15.

[7] Polly Lane, “Rallies seek end to Central American intervention,” Seattle Daily Times, April 11, 1987, 8.

[8] Jette, “The Development of the WSRC;” 1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics, United States, Page 329 Table 253, U.S. Department of Commerce, https://www.census.gov/library/publications/1992/dec/cp-1.html

[9] Jette, “The Development of the WSRC.”

[10] Helena Stephens, interview by Saul Gonzalez, May 16, 2024, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Oral History Project, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington, Seattle. https://archive.org/details/StephensHelena_WSRCOHP_20240516

[11] Ibid.

[12] Larry Gossett, letter in Washington State Rainbow Coalition Rainbow News, no. 2 (Nov./Dec. 1989), Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 8, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1991, Accession No. 5799-001.

[13] Rainbow Record, vol. 1, no. 1 (Spring 1990), Whatcom County Rainbow Coalition, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 6, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1990, Accession No. 5799-001.

[14] “Rainbows around the State,” Rainbow News, vol. 2, no. 1 (February/March 1990): 6, Washington State Rainbow Coalition, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 8, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1991, Accession No. 5799-001.

[15] Nancy San Carlos, “News Around the State,” Rainbow News, vol. 3, no. 1 (Winter 1991): 4, Washington State Rainbow Coalition, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 8, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1991, Accession No. 5799-001.

[16] Phil Bereano Interview, interview by Saul Gonzalez, May 9, 2024, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Oral History Project, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington, Seattle. https://archive.org/details/BereanoPhil_WSRCOHP

[17] Proposed Agenda for the 1990 WSRC Retreat, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 6, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1990, Accession No. 5799-001.

[18] Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat - 1990 Goals and Vision, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 6, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1990, Accession No. 5799-001.

[19] Sylvia Smith Letter to Dave, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 6, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1990, Accession No. 5799-001.

[20] Letter from Larry Gossett, Rainbow News, vol. 3, no. 1 (Winter 1991), Washington State Rainbow Coalition, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 8, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1990, Accession No. 5799-001.

[21] Robert Ewing, “Rainbow Coalition’s Victories in 1990,” Rainbow News, vol. 3, no. 1 (Winter 1991), Washington State Rainbow Coalition, Cindy Domingo Papers, Box 12, Folder 8, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Retreat, 1989–1990, Accession No. 5799-001.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Letter from Larry Gossett, Rainbow News, vol. 3, no. 1 (Winter 1991).

[24] Thaddeus H. Spartlen, Rainbow Rap vol. 1, no. 3 (Oct.–Dec. 1995), Washington State Rainbow Coalition, Rosalinda Guillen Papers, Box 1, Folder 2, Rainbow Coalition [Coalición Rainbow], 1989–1995, Accession No. 5799-001, Special Collections, University of Washington.

[25] “Rainbow Coalition President Resigns,” Rainbow Rap vol. 1, no. 3 (Oct.–Dec. 1995), Washington State Rainbow Coalition, Rosalinda Guillen Papers, Box 1, Folder 2, Rainbow Coalition [Coalición Rainbow], 1989–1995, Accession No. 5799-001.

[26] Bob Barnes, interview by Saul Gonzalez, May 30, 2024, Washington State Rainbow Coalition Oral History Project, Labor Archives of Washington, University of Washington, Seattle. https://archive.org/details/BarnesBob_WSRCOHP

[27] Oscar Rosales Castañeda, “The Creation of the Washington State UFW in the 1980s,” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/farmwk_ch9.htm.

[28] Johnson, interview by Saul Gonzalez, June 12, 2024.

.png)