In Carlos Bulosan’s renowned 1946 novel of the Filipino American immigrant experience, America is in the Heart, the protagonist returns to the city of Seattle, his original port of entry, after a harrowing journey of racial violence and discrimination. Wandering the city streets penniless and disillusioned, he comes upon a bridge, where he spies the commotion of a union picket below. Running down an embankment to investigate, he receives his first introduction to the labor movement. 1

Like much of Bulosan’s novel, this brief episode is a fictional reimagining of actual events. While Bulsoan never mentions it by name, incidental details place the scene on Seattle’s 12th Avenue South Bridge, a green span of steel crossing two hundred feet above Dearborn Street. Throughout the 1930s, the time period of Bulosan’s novel, Dearborn Street was host to a regular Teamster picket of a laundry business. 2 What makes the scene significant, however, is not that it actually happened. The significance lies instead in what was to come.

In 1974,almost four decades after Bulosan crossed it in his novel, the 12th Avenue South Bridge was renamed and rededicated in the name of Dr. Jose P. Rizal, the martyred Filipino patriot and novelist. It was an appropriate dedication. Built in 1912, one of the oldest steel structures in Washington State, the bridge ties together Seattle’s International District and Beacon Hill, two of the city’s historically Asian American working-class neighborhoods. Renamed through the efforts of civic-minded members of Seattle’s Filipino community, it was accompanied by the building of a park in Rizal’s honor on land adjacent to the bridge.

By 1974, Bulosan was dead and buried in Seattle, his work only beginning to be rediscovered by a new generation of young Asian Americans. 3 Nevertheless, Dr. Jose P. Rizal Park and Bridge were testaments to Bulosan’s generation, the Filipino Americans he had portrayed in his work. Beginning where America is in the Heart ends, at the end of World War II, the story of Dr. Jose P. Rizal Bridge and Park is a story of the rise of an established Filipino community in Seattle and their on-going efforts to make the city their own.

Philippine Seattle

Seattle’s history has long been intertwined with that of the Philippines. Beginning with the Spanish American War of 1898 and continuing through the brutal counter-insurgency that followed US colonial possession of the islands, the business ofshipping troops and supplies to the Philippines contributed to Seattle’s early growth. 4 This fact is reflected in various Seattle city parks dating from that era: Volunteer Park in Capitol Hill, named for the war’s volunteer soldiers;5 Woodland Park, which hosts a statue honoring fallen soldiers from the Spanish-American War and the “Philippine War;” 6 and the original names of downtown’s City Hall Park and Magnolia’s Discover Park, “Fortson Square” and “Fort Lawton” respectively, both named for army men who died during the U.S. campaign to subdue the Philippines.7

United States rule over the Philippines provided an opening for thousands of Filipino migrants to cross the Pacific in the early twentieth century. While U.S. law denied them citizenship on the basis of race, they nevertheless could travel to the United States without passports under the ambiguous status of “nationals” until 1934.8 Most came to the United States to work, hoping to make money and return home.9In contrast to other first generation Asian Americans of that era, many also came to pursue higher education.10 As students they took low wage jobs to put themselves through school, but after graduation often discovered they were still segregated into the same menial positions. Among these immigrants were Vic Bacho and Trinidad Rojo, two men who would come to play central roles in the campaign to rename the bridges and establish Dr. Jose P. Rizal Park.

Eutiquio de La Victoria “Vic” Bacho was born to a middle-class family in Talisay, Cebu on November 20, 1903. After attending junior college in the Philippines, Bacho came to the United States in 1927 intending to continue in school. Instead, Bacho found racial discrimination, forcing him to work seasonal jobs throughout California. Spurred by the injustices he had experienced, Bacho turned to public engagement, becoming a central figure in Stockton, CA’s Filipino community. After serving in the military during World War II, he moved to Seattle to join his brother Vince. Employed at Boeing, Vic Bacho slowly worked his way through a degree at the University of Washington, earning a BA in Political Science at the age of 54. Throughout, he was active in a number of Filipino fraternal and community organizations, and remained highly political, campaigning for local and national Democratic candidates as a leader in the Filipino-American Political Action Group of Washington (FAPAGOW). Bacho would later put his political skills to use in building support for the Rizal Bridge and Park.11

Trinidad Rojo hailed from the Ilocos region of the Philippines – not the Visayan Islands, like Bacho. Otherwise, their backgrounds were very similar. Born May 25, 1902, Rojo came to the United States in 1926 at the age of twenty-four to continue his education. Working his way through the University of Washington, Rojo labored in the few occupations open to Filipinos at the time, first in domestic service, then as a seasonal worker in fields and canneries. He graduated from the University of Washington in 1930 with a bachelor’s degree in English, Comparative Literature and Drama, with a minor in sociology.12

Later pursuing graduate studies at Stanford and Columbia, Rojo described his life as being “like a yo-yo between the campus and the labor unions.”13 In 1939, he was elected to the first of four terms as president of Local 7, a union of Filipino cannery workers that was a central institution in the Seattle Filipino community. Relations within Local 7 were often fractious. Rojo held a bitter hatred for Carlos Bulosan and the union president who hired Bulosan to write for Local 7, Chris Mensalves, who Rojo blamed for mismanaging union funds.14Nevertheless, Rojo considered himself a moderate – working with conservatives and communists alike – and among his contemporaries, he was known for being a more or less neutral figure in the union, if having a big personality. 15

Rojo’s big personality made him eccentric; he described himself all at once as a sociologist, labor economist, dramatist, poet, philosopher and a businessman in real estate and finance.16 And Rojo was ambitious and creative. His voluminous papers, left to the UW Libraries, are full of big ideas, from fashioning “floating universities” out of decommissioned aircraft carriers,17 to arranging for donations of Philippine animals to Seattle’s Woodland Park Zoo.18 Later, he would petition to rename Washington State’s volcanic Mount St. Helens for Jose Rizal.19 But as outlandish as some of his ideas could seem, Rojo’s ambition would play a big part in making Rizal Park and Bridge a reality.

Naming Rizal Bridge

As the Mount St. Helens petition exemplified, many of Rojo’s big ideas centered on ways to honor Jose Rizal. Born in 1861 in Calamba, Laguna, Phillipines, Rizal had traveled to Spain to study in the home country of his colonizer. Worldly and learned, Rizal spoke over ten languages and was, among many other things, a poet, historian, painter, sculptor, and medical doctor. A fervent advocate for Filipino rights under Spanish rule, he authored two incendiary anti-colonial novels, Noli Mi Tangere and El Filibusterismo. Blamed for stirring unrest against the colonial government, the books led to Rizal’s execution by the Spanish in 1896, a few short years before the Spanish-American War.20 Rizal’s martyrdom transformed his life and legacy into symbols, invoked to serve a variety of political purposes. Filipino revolutionaries appealed to his memory, but so too did American colonial officials, who promoted Rizal as a safe anti-Spanish figure, an alternative to more militant Filipino revolutionaries. 21

As students who came of age in the Philippines during the American colonial period, Rojo and Bacho held great admiration for Rizal. In many ways, Rizal was central to their identities. Not unlike Rizal, Bacho and Rojo traveled to the homeland of the colonial power seeking education. As a man of scholarly talents, Rizal embodied the qualities they aspired towards as students. Emigrants of Rojo and Bacho’s generation made Rizal a part of nearly all their activities as Filipinos – from the names of their fraternal organizations (such as Cabelleros De Dimas Alang, derived from Rizal’s pen name)22 to their community celebrations (Rizal Day, held each year on December 30, the anniversary of his execution).23 In his memoir, Bacho explained the importance of Rizal Day to Filipinos in America. “The 30th of December was a time to remember the homeland, a time to feel patriotic and nostalgic. In observance of the national hero’s day, the civic minded among the community made plans every year.”24

For Bacho, Jose Rizal was the embodiment of Filipino civic engagement, and civic engagement was a way for Filipinos to better their selves and their standing in America. Explaining later why he had been driven to campaign for the Rizal Bridge and Park, Bacho drew upon the bitter memory of being slapped and spat upon by an inebriated white woman one New Years Eve in San Francisco. Restraining himself from responding to the racist affront, which, he was certain, could bring mob violence down upon him, Bacho stewed. “What can a Filipino do to improve his image so he can be recognized, respected, and treated as an equal?” the incident left him asking. “How can I or anyone else prove that a Filipino is just as intelligent as any white man? I had no answer to these questions but somehow something flashed in my mind and it was the image of Jose P. Rizal.” Over time, the flashes of Rizal in Bacho’s mind gained shape. “In my mind was a vision, a dream – if you will – that someday, somewhere, there would be a Rizal Park with the statue of the man in it.” 25

Trinidad Rojo shared Bacho’s dream. Rojo’s own aspirations to dedicate a memorial to Rizal dated back to at least 1960, when a Seattle chapter of “The Friends of Rizal” was inaugurated to promote relations between the city and the Philippines.26 The effort that eventually led to the Rizal Bridge in Park, however, began in earnest on May 30, 1973. The University of Washington Filipino Alumni Association, of which Bacho was president, had organized a program honoring Filipino American high school graduates. Trinidad Rojo was master of ceremonies and Seattle Mayor Wes Uhlman attended as a guest speaker. As the event was wrapping up, Rojo casually mentioned the idea of naming a street after Rizal to Mayor Uhlman. Uhlman was receptive, and Rojo and Bacho followed up with letters in the days afterwards, leading the Mayor to proclaim the week of June 19, 1973 “Dr. Jose Rizal Week.”27

In 1973, Vic Bacho would turn seventy. Trinidad Rojo was seventy-one. They were now elders, and the Seattle Filipino community had grown past the days of itinerant bachelorhood that had first greeted Bacho and Rojo’s generation in America. Many had settled down with families, and combined with a new wave of mostly middle-class Filipinos that began arriving after US immigration reforms in 1965, the Filipino population in Washington State had risen from 2,222 in 1940 to 11,462 in 1970.28

As one generation gave way to another, identification with Rizal was no longer as central to Filipino identity as it had once been. In the Philippines, where the radical left was growing in response to President Ferdinand Marcos’ imposition of martial law, the ambiguity of Rizal’s support for the anti-colonial revolutionaries of his time made his image increasingly unpopular.29 Divisions in the Philippines echoed in Seattle’s community, where contentious views about Marcos split along lines of family history, class and political orientation.30 Rojo, in particular, was a supporter of Marcos and engaged in arguments with young anti-Marcos activists. 31 As a result, many of Seattle’s younger Filipino American activists, focused on their own campaigns, did not play central roles in establishing Rizal Bridge and Park. It would largely be an accomplishment of earlier immigrants like Bacho and Rojo who had achieved success in business and education, as well as other middle-class Filipinos who had arrived after 1965.

Following Mayor Uhlman’s proclamation of Rizal Week, Bacho, Rojo, and their community allies formed a “Street Naming Committee” to identify a street to petition the city to re-name in Rizal’s honor. They identified possibilities in and around the city’s International District, including King Street (known as Seattle’s “Little Manila” in the early years of Filipino migration) and Maynard Street, as well as Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Twelfth Avenues. 32 Forwarding their suggestions to the Mayor, Bacho flexed his political muscles, alluding to the Mayor’s recent actions in support of Black civil rights and reminding Ulhman of his upcoming re-election campaign:

We know that while you have done quite well for the Negros in their struggle for social justice you have done very little if at all, for the employment of qualified Filipinos. We believe that if the selection and dedication of a Dr. Jose Rizal Street can be accomplished within a short period of time, the effort to win them back may not be too difficult. As the Cabelleros De Dimas Alang’s chairman and therefore its Pacific Northwest representative, the naming of Dr. Jose P. Rizal Street will unite the members to campaign actively for you.33

The Mayor referred the matter to the city’s Superintendent of Public Works, Alfred Petty, who informed Bacho that renaming streets of longstanding was against city policy. Instead, Petty suggested renaming King County’s new domed stadium (later known as the Kingdome) “Jose Rizal Stadium” – an odd suggestion, because Asian American activists had been fervently protesting the stadium’s development, which threatened the vitality of the International District. Bacho recalled that he “could not help but chuckle a bit upon hearing the suggestion.”34

On November 4, 1973, Mayor Uhlman wrote to Trinidad Rojo with an amenable solution: renaming 12th Avenue South Bridge, as well as undeveloped parkland nearby, for Jose Rizal.35 The Street Naming Committee accepted, and the city’s Board of Public Works made the rededication of the bridge official shortly after in December. Several months later, in March 1974, Bacho received word that the park was also official. Finally, in a ceremony on June 19, 1974, the one hundred thirteenth anniversary of Rizal’s birth, the bridge and park were formally rededicated. Dr. Jose P. Rizal Bridge and Park were now a reality.36

Making Rizal Park

A few months following the dedication of the park and bridge, a letter arrived for Vic Bacho from Seattle’s Superintendent of Parks and Recreation, David Towne. Outlining the costs of the park’s development, the letter ended offering well wishes: “Good luck in pursuing funding for this most unusual view park.” The letter took Bacho by surprise. He had assumed the city would fund the development of the park. While the city had prepared a twenty-page master plan, the responsibility fell to the larger Filipino community to clear the overgrown parkland and seek the resources to put the plan into place.37

Despite some early disagreement within the community over how the park would come together, a united Rizal Bridge & Park Development Committee emerged in 1977 to continue to petition the city for funding, meeting with city council members and writing letters of ever-stronger tone.38 By the end of 1978, they had enough funds to hire an architectural firm to begin building the park. Aspirations for the park included formal gardens, an outdoor theater, a community center, a museum, a library and recreation space, play fields, and a children’s play area.39 But as construction planning commenced, it quickly became clear that most of the site was too unstable to develop on. Even most of the original 1974 master plan would have to be scrapped.40

Perched on the northwest corner of Seattle’s Beacon Hill, the park site was susceptible to landslides, a problem that dated back to the mid-1920s when city engineers had extensively re-graded the hillside. The 1920s re-grade was itself a response to damaging mudslides caused by yet another, earlier, poorly executed land development. The original 1912 Dearborn re-grade had ploughed through the hill, making the 12th Avenue Bridge necessary and razing a low-income neighborhood in the process. 41 City engineers had hoped their work would boost property values. Instead, it depreciated them.42 Now, in 1974, the area surrounding Dearborn Street was a tangle of empty hillsides and loud free-way interchanges. It was “really a very bad place” for a park, Vic Bacho admitted.43

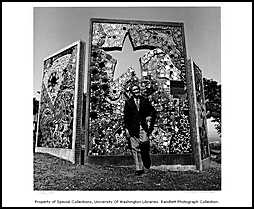

None of this made the Development Committee any less determined to see the park through to completion. With the funds wrestled from the city, the architectural firm Elaine Day LaTourelle and Associates was enlisted to develop an amphitheater, play area, shelter house, parking, and a bathroom. Additionally, Filipino American artist Val Laigo was commissioned to produce a colorful mural, “East is West,” an abstract expressionist tribute to the converging cultures of the United State and the Philippines. Finally, on June 7, 1981, a rainy Sunday afternoon, Dr. Jose P. Rizal Park would be formally dedicated.44 After seven years of concerted striving, a sorry, forgotten location had been turned into what would become one of Seattle’s most popular viewpoints.

A Symbol of Filipino Identity

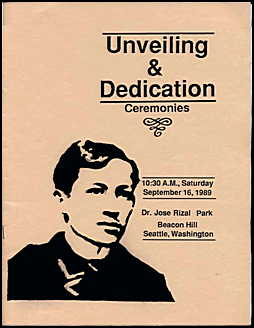

While the park was officially completed in 1981, improvements did not end there. What had once been a Street Naming Committee, then a Development Committee, was now the “Dr. Jose P. Rizal Bridge & Park Preservation Society,” with E.V. Vic Bacho continuing to lead as chairman. In 1989, the Society at last installed one of the 1974 master plan’s central features, a prominent bronze bust of Dr. Rizal designed by Filipino sculptor Anastacio Caedo. Funding for the bust was secured thanks to the efforts of, among others, Zenaida F. Guerzon, an active figure in the community and a longtime ally of the project, and Seattle councilwoman Dolores Sibonga.45 It was also funded in part by a creative time capsule campaign, mirroring a similar capsule described in Rizal’s novel Noli Mi Tangere, installed underneath the statue – a fitting metaphor for the endurance into the future of a Filipino American community in Seattle.46 Meanwhile, Trinidad Rojo, headstrong to the very last, resigned in protest from the Rizal Park Preservation Society upon learning Rizal’s statue would not be life-size. 47

Today, the park remains a central gathering place for Seattle Filipino Americans, who continue to use it for events and festivals. In 2012, another memorial was added, this one to Filipino American World War II veterans, survivors of the infamous Bataan Death March.48 As a public park, the area has also grown to include new users. In 2005, internet tech-giant Amazon.com, then headquartered across the street, helped develop lower portions of the park into an off-leash area for dogs. Later plans to develop the area for a community garden and further use by the Filipino community drew protests from dog owners.49

Both Rizal Park and Rizal Bridge continue to attract everyone in Seattle for their impressive views of the city, Elliot Bay, and the Olympic Mountains. Beyond their everyday uses as sites of recreation, however, Rizal Park and Bridge’s most valuable, lasting contributions are as symbols. Writing way back at the beginning of the endeavor in 1975, this had been Trinidad Rojo’s hope:

The philosophy behind the Seattle Rizal Memorials ought to be and must be humanism, cosmopolitanism and internationalism, with an enlightened pragmatic motive of increasing magnetic attractions to local, national, and international tourism, to accelerate Seattle’s march towards its progress to its status of a major world city, which she richly deserves.50

In drawing upon the themes of cosmopolitanism and internationalism, Rojo appealed to long-standing tropes about Seattle that dated to well-before World War II. Poised on the Pacific Rim, Seattle’s boosters have long imagined it as a city of world importance, and to them, the presence of Asian communities is evidence of that.51

In 1999, Mayor Paul Schell picked up these themes and amplified them anew when he chose to light Rizal Bridge to celebrate the millennium. For New Year’s Eve, Schell had aspired to light all of Seattle’s major landmarks to celebrate the millennium, but due to a shortage of money and logistical issues, the city was only able to light two. Following a speech where he appealed to the bridge as a metaphor connecting countries internationally, Schell flipped the switch on New Year’s Eve. As he did so, those attending, including original members of the Jose P. Rizal Park and Bridge Preservation Society, sang “My Country” in Tagalog.52

As the Society’s song highlighted, Rizal Bridge and Park are less about the achievements of Seattle than they are about the accomplishments of Filipino Americans, accomplishments won through decades of perseverance and struggle. Peter Bacho, the nephew of Vic Bacho, an attorney for the Bridge & Park Society, and a future acclaimed novelist, recognized this aspect of the Bridge and Park in 1983. Recalling the history of racist legal exclusion of Filipinos from U.S. citizenship, the efforts of politically savvy leaders like his uncle, and the emergence of Filipino youth activism in the 1960s, Bacho stressed the ultimate importance of Rizal Bridge and Park. “It is within this context of growth that the success of Rizal Park must be viewed,” he wrote.

What is important to understand… is that the City’s positive response to Rizal Park was based, at least in part, upon a realization that Filipino Americans had reached a level of political maturity. The omen is positive. It means that Filipino concerns, although they may at times be outweighed by competing concerns, can no longer be ignored.53

The significance Bacho recognized in 1983 continues to resonate. In the 2007 song “Joe Metro” by the hip-hop group Blue Scholars, Filipino American MC Geological narrates his morning bus ride to work, a political parable capturing vividly the daily toils of life and labor in Seattle. In the final verse, he travels, appropriately, across Rizal Bridge.

Now we headed downtown to trade our labor for cash

I thank the navigator once and walk fast

I walk past the next round of cats to jump on it

Locked in deep thought, we ride around in silence

And cross Rizal Bridge 54

Geologic crosses the bridge as a symbol of three generations of Filipino American history. Until Dr. Jose P. Rizal Park and Bridge, the only Seattle monuments recognizing the city’s connection to the Philippines – Volunteer Park, Woodland Park, Fort Lawton and Fortson Square – were paeans to United States imperial ambitions. Rizal Park and Bridge, much in the spirit of the man they are named for, refuse to allow imperialism to define the Filipino experience in Seattle.

Copyright © Andrew Hedden 2013

1 Carlos Bulosan, America is in the Heart: A Personal History (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973), 153.

2“Pickets Leave After Eight Years; Cleaner ‘Lonesome,’” _Seattle_Times, 14 September 1941, 7. Another example of Bulosan’s fictionalization of actual events in America is in the Heart is discussed by Dorothy Fujita-Rony, American Workers, Colonial Power: Philippine Seattle and the Transpacific West, 1919-1941 ( Berkley, CA: University of California Press, 2003), 144.

3E. San Juan Jr., “Revisiting Carlos Bulosan,” Toward Filipino Self-Determination: Beyond Transnational Globalization (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2009), 62-63.

4 Fujita-Rony, American Workers, Colonial Power, 35; Fujita-Rony, “History through a Postcolonial Lens: Reframing Philippine Seattle,” Pacific Northwest Quarterly Volume 102, Number 1 (Winter 2010-2011), 4.

5 Donald N. Sherwood, “ Volunteer Park,” Sherwood Park History Files, Seattle Parks and Recreation, accessed March 29, 2013,http://www.seattle.gov/parks/history/VolunteerPk.pdf .

6 “Hiker Memorial Statue,” Seattle Outdoor Art, accessed March 29, 2013, http://www.seattleoutdoorart.com/

show.php?cat=medium&catval=bronze&id=161 .

7 Sherwood, “Dr. Jose Rizal Park,” Sherwood Park History Files, Seattle Parks and Recreation, accessed March 29, 2013,http://www.seattle.gov/parks/history/RizalPk.pdf .

8 Rick Baldoz, The Third Asiatic Invasion: Migration and Empire in Filipino America, 1898-1946 ( New York: NYU Press, 2011).

9 Fujita-Rony, American Workers, Colonial Power, 39.

10 Ibid, 51.

11 Bacho, E.V. “Vic,” The Long Road: Memoirs of a Filipino Pioneer (Seattle, WA: Self-published, 1992), 8, 10-16, 28, 32, 38-40. “Bacho clan in the making,” in Rizal Park: A Symbol of Filipino Identity, ed. D.V. Corsilles (Seattle: Magiting Corporation, 1983), 194-195; Ernie Umali, “FAPAGOW: Testing the Filipinos’ Political Muscle,” in Corsilles, 51; Carole Beers, “Vic Bacho, 96, Filipino Leader,” Seattle Times, December 17, 1996, accessed March 29, 2013,http://community.seattletimes.nwsource.com/

archive/?date=19961217&slug=2365459 .

12 Trinidad Rojo, interview by Carolina D. Koslosky, FIL-KNG75-17ck, 18 February 1975 and 19 February 1975, Washington State Oral/Aural History Program, 1, 8, 11.

13 Rojo, “Food Tobacco and Allied Workers of America, CIO Local 7, Now, International Longshoremen and Warehouse Union (ILWU), Local 37,” 1. Box 1, Trinidad Rojo Papers 1932-1988, University of Washington Special Collections.

14 Micah Ellison, “The Local 7/ Local 37 Story: Filipino American Cannery Unionism in Seattle 1940-1959,” Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project, accessed March 29, 2013,local_7.htm . Rojo claimed on hearsay that Bulosan’s America is in the Heart was ghost-written; see Rojo, “Food Tobacco and Allied Workers of America,” 18.

15 Michael Brown, Victorio Acosta Velasco: An American Life ( Lanham, Maryland: Hamilton Books, 2008), 85.

16 Rojo, “Food Tobacco and Allied Workers of America,” 1.

17 Rojo, undated radio transcript, Box 1, Trinidad Rojo Papers, 1932-1988, University of Washington Special Collections.

18 Rojo, letter to David L. Towne, Superintendent of Seattle Parks and Recreation, May 21, 1975, tucked inside University of Washington Libraries copy of David L. Towne, “Master Plan for Rizal Park,” (Seattle: Department of Parks and Recreation, 1975).

19 Rojo, “An Essay: Rizal’s Place in World History,” in Corsilles, 22-24.

20 Benedict Anderson, Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination ( London: Verso, 2005). See also Ambeth O. Campo, Rizal Without the Overcoat ( Pasig City, Philippines: Anvil Publishing, 2000).

21 Roland L. Guyotte and Barbara M. Posadas, “Celebrating Rizal Day: The Emergence of a Filipino Tradition in Twentieth-Century Chicago,” in Feasts and Celebrations in North American Ethnic Communities, edited by Ramón A. Gutiérrez and Geneviève Fabre (Albugerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1995), 113.

22 “CDA, Inc. and the Filipinos in America,” in Corsilles, 179.

23 Fujita-Rony, American Workers, Colonial Power,162; Guyotte and Posadas, “Celebrating Rizal Day,” 111-127.

24 Bacho, The Long Road, 37.

25 Ibid, 42.

26 Towne, “Master Plan for Rizal Park.” Reprinted in part in the Filipino American Herald, May 15, 1975, 6.

27 Emilio R. Castillo, “Dr. Jose Rizal Park, A Brief Introduction: How Rizal park came to be…” in Corsilles, 3; Bacho, “ Seattle’s Rizal bridge & park: a dream realized,” 5.

28 Fujita-Rony, “History through a Postcolonial Lens: Reframing Philippine Seattle,” 8.

29 Anderson , 130, note 13.

30 Ligaya Rene Domingo, “Building a Movement: Filipino American Union and Community Organizing in Seattle in the 1970s” (Phd. Diss., University of California, Berkeley, 2010), 63-65.

31 Emma Catague, Interview by Ron Chew, Remembering Silme Domingo & Gene Viernes: The Legacy of Filipino American Labor Activism ( Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2012), 59.

32 In addition to Bacho and Rojo, Committee members included Lorenzo Anunciacion, Dolores Sibonga, Dina Valentin, Prudencio Mori, Kathleen Doss, Emiliano A. Francisco, Angelina Francisco, Steve Oh, Gerald Laigo, Ponce Torres, Bob Santos, and Gene Navarro. Bacho, “ Seattle’s Rizal bridge & park: a dream realized,” 5-6; Lorenzo P. Anunciacion, “An Eyewitness Account: Rizal Bridge & Park story: behind the scenes,” in Corsilles, 42.

33 Bacho, “ Seattle’s Rizal Bridge & Park: A Dream Realized,” 6.

34 Ibid, 7.

35 Anunciacion, 42.

36 Castillo, 3; “Bridge, park named after Filipino patriot,” Seattle Times, 16 June 1974, 26.

37 Bacho, “ Seattle’s Rizal Bridge & Park: A Dream Realized,” 9; Bacho, The Long Road, 50.

38 Bacho, “ Seattle’s Rizal Bridge & Park: A Dream Realized,” 9. Members included Silvestre Tangalan, president, Filipino Community of Seattle, Inc.; Fred Cordova; Salvador del Fierro, Sr., Filipino Inc.’s board of trustees; Leo Lorenza, Filipino Senior Citizens, Inc.; Vincent A. Lawsin, Filipino-American Action Group of WA, Inc.; Zenaida F. Guerzon; Auerelia del Fierro; Ficardo and Rosita Farinas; Dolly Castillo; DV Corsilles, editor, Bayanihan Tribune; Francisco, Philippine American Herald; and Peter Bacho, legal consultant.

39 Wanda Reed, “Beacon Hill Park is Memorial to Hero,” in Corsilles, 26; reprinted from Beacon Hill News, 22 February 1978.

40 Bacho, “ Seattle’s Rizal Bridge & Park: A Dream Realized,” 11.

41 Matthew Klingle, Emerald City: An Environmental History of Seattle( New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 115.

42 William H. Wilson, Shaper of Seattle: Reginald Heber Thomson’s Pacific Northwest ( Pullman, WA: Washington State University Press, 2009), 109.

43 Reed, “ Beacon Hill Park is Memorial to Hero,” 26.

44 Bacho, “ Seattle’s Rizal Bridge & Park: A Dream Realized,” 12.

45 Bacho, The Long Road, 55, 59.

46 “Unveiling & Dedication Ceremonies, September 16, 1989,” Event Program, in possession of the Filipino American National Historical Society Archives, Seattle, WA.

47 Bacho, The Long Road, 60.

48 Nancy Bartley, “New Seattle monument honors bravery of Bataan soldiers,” Seattle Times, 4 February 2012, accessed April 5, 2013,http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/

2017426870_veterans05m.html .

49 “Parks department a mediator between dog owners, others who want to use city parks,” Seattle Times, 7 November 2011, accessed April 5, 2013,http://seattletimes.com/html/localnews/2016707306_dogparks07m.html.

50 Rojo, letter to David L. Towne.

51 Shelley Sang-Hee Lee, Claiming the Oriental Gateway: Prewar Seattle and Japanese America ( Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, 2010).

52 Jeff Hodson, “Lights, Camera… Millennium; City Illuminates Bridge To Span The Ages,” Seattle Times, 31 December 1999, accessed April 5, 2013.

53 Peter Bacho, “Are we now politically mature? Jose Rizal Park a positive omen” in Corsilles, 48.

54 Blue Scholars, “Joe Metro,”Bayani, 2007 by Massline/Rawkus Records.