Strategies for Overcoming Antibiotic Resistance

In the last module, you learned about what antibiotic resistance is, how it occurs, and the risk factors that cause it to emerge and spread in the health care setting. In this module, you will learn about strategies to reduce and prevent the occurrence of antibiotic resistance. These strategies include infection prevention and control (IPC), such as observing proper hand hygiene and environmental cleaning; triaging and isolating/cohorting patients with infections that are antibiotic-resistant; practicing antimicrobial stewardship; and conducting surveillance. You will also learn about how to use the World Health Organization’s (WHO) multimodal strategies to implement activities to reduce and prevent AMR.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- describe evidence-based IPC practices to prevent and control the spread of antibiotic resistance, and a multimodal approach for stepwise implementation.

Learning Activities Estimated time:

-

Case Study (10 min)

A few days after the death of Nega, two other small neonates are reported sick with an infection:

- Aida, also preterm (31 weeks), was born two days earlier; she has been diagnosed with a respiratory syndrome similar to Nega’s.

- Kofi was born at term four days earlier; he is diagnosed with a urinary tract infection.

Given the limited amount of time that elapsed since Nega’s death, Dr Azeb decides to take immediate action: she takes blood samples from both neonates, even though the infections are not severe. She also decides to ask the laboratory to perform susceptibility testing on the samples, specifically to look for carbapenem- and colistin-resistance. In the meantime, Dr Azeb consults with the hospital pharmacists, infectious disease experts and IPC team to agree on a plan of action.

On a piece of paper (or in the box below), list two or three IPC actions you could take to stop the potential outbreak. Then click or tap the Compare answer button.

In this module, you will learn about strategies to fight antibiotic resistance.

-

Elements to Combat Antibiotic Resistance (5 min)

Providing clean water, basic sanitation and good hygiene (WASH) will help stop the spread of antimicrobial resistance. According to the United Nations, at least 1.8 billion people globally use a source of drinking water that is faecally contaminated; 2.4 billion lack access to basic sanitation services, such as toilets or latrines.1

It is also crucial to implement effective IPC measures. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) published a report on the cost-effectiveness of mixed public health interventions to prevent AMR. They found that all mixed interventions were cost-effective; most of these interventions actually saved money (i.e., the money earned exceeded the funds spent), in particular those that included implementing IPC in hospitals. So, how exactly can we combat antibiotic resistance? We can:

- conduct surveillance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including screening of high-risk patients;

- provide antimicrobial stewardship and monitoring of antibiotic consumption;

- put in place triage and identify patients with antibiotic resistance so that we can put contact precautions in place;

- practice hand hygiene according to the WHO’s 5 Moments;

- clean and disinfect the environment (see the Standard Precautions Environmental Cleaning module);

- decontaminate medical devices (see the Decontamination and Sterilization module);

- train all health care workers on key IPC measure that stop the spread of AMR; and

- monitor infrastructure for IPC and IPC practices.

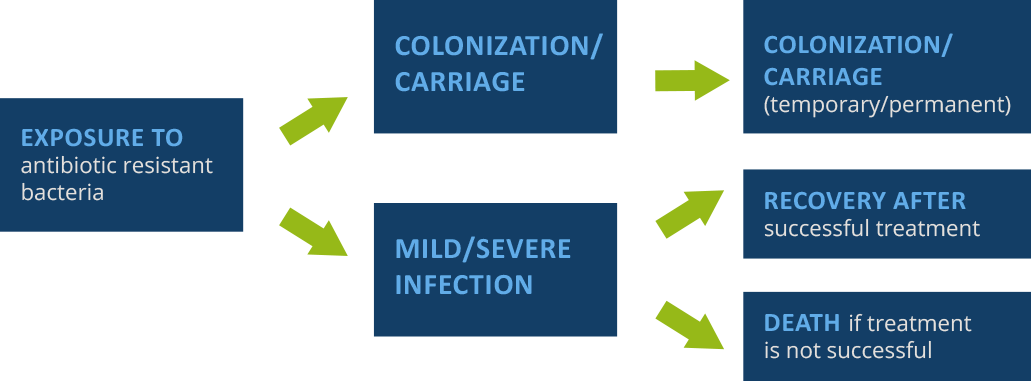

The diagram below shows the exposure pathway of a patient, beginning with exposure and going through potential outcomes.

Source: Damani N. Manual of infection prevention and control. Oxford University Press, 2012.

The exposure of the patient to antibiotic-resistant bacteria is itself a risk factor. Colonization/carriage: antibiotic exposure may influence frequency/persistence of colonization/carriage (i.e., presence of bacteria on the body without causing disease).

Note that colonization can occur without necessarily resulting in an infection. However, anyone who has been colonized can expose patients, and thus infect/colonize them. IPC prevents exposure, as well as colonization and infection.

The purpose of IPC interventions is to prevent initial exposure, or ongoing transmission after infection or colonization. There are two types of interventions used to combat antibiotic resistance. Click or tap on each tab to read about them.

Horizontal Interventions

Horizontal interventions seek to control all health care-associated microorganisms. In other words, these types of interventions are not specific to any one type of organism; rather, they will have a broad preventative effect. Some key horizontal interventions include:

- performing hand hygiene according to the 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene;

- using invasive devices only when indicated;

- decontamination of reusable medical devices;

- cleaning and/or disinfecting the environment; and

- practicing antimicrobial stewardship.

Vertical Interventions

Vertical interventions use organism-specific measures. In other words, these are interventions that are known to be effective against known or suspected organisms. Some key vertical interventions include:

- screening targeted patients at risk for carrying antibiotic-resistant organisms;

- isolating (or cohorting) a confirmed or suspected patient based on the mode of transmission;

- targeted decolonization (if applicable)— e.g., Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) decolonization in preoperative surgical patients.

In this module, we will explore these interventions further, and look at how they help to combat antibiotic resistance.

-

Surveillance & Monitoring (5 min)

Surveillance of antibiotic resistance and monitoring of IPC practices are crucial in order to understand the local situation and put in place appropriate prevention action and develop tailored antimicrobial stewardship strategies. It focuses on outcomes and is critical to detect carriage and infections due to both antimicrobial resistant and sensitive pathogens. Monitoring focuses on process and structure (e.g., hand hygiene compliance, isolation room capacity). You can monitor to ensure that staff are practicing proper IPC processes, such as:

- hand hygiene compliance;

- environmental cleaning protocol compliance; and

- compliance with device insertion, management, and removal standard procedures.

Analysis and interpretation of surveillance and monitoring data are critical for timely reporting and feedback, which are an essential element to translate data into action. Your IPC programme should conduct surveillance of AMR and HAI outcomes to detect colonized or infected patients and to track the burden of infection and resistance over time in your facility, in order to implement the proper vertical IPC practices for the microorganisms identified. Surveillance and monitoring complement each other; they should be conducted at the same time.

Monitoring

Click or tap on each tab to learn more about how to monitor compliance.

Hand Hygiene

To monitor whether staff are performing hand hygiene reliably, use an observation tool to monitor and provide feedback. The WHO Hand Hygiene Self-Assessment Framework 2010 (also listed in the Resources section) is one such tool. A diagnostic and baseline assessment tool, it uses a set of indicators to help identify areas that need improvement. Health care facilities can track their progress using a number of hand hygiene resources, from promotion and activities to planning new campaigns.

Environmental Cleaning

There are several types of environmental cleaning audits. Direct observation can be either a visual assessment such as an inspection after cleaning, or observation of a staff member while they are cleaning. Patient/resident satisfaction surveys are an example of indirect observation. In this case, you are getting them to be your eyes and tell you what they see in terms of cleanliness. Direct and indirect observation both answer the question, “Does it look clean?” In addition, environmental indicators of thoroughness of cleaning and cleanliness exist, and they should be used when feasible, because more reliable and less prone to subjective interpretation.

These other measurements of cleanliness—such as environmental cultures, ATP and the use of environmental markers—measure the residual bioburden, i.e., germs that may have been left behind after cleaning. This type of audit answers the question, “Are germs still present?” Routine environmental swabbing is not recommended. A form for environmental cleaning monitoring is available from CDC and is listed in the resources section.

WHO has developed a facility assessment tool (Infection Prevention and Control Assessment Framework, available in the resources section) to support facility-level implementation of the WHO Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes. This framework will help you assess existing IPC activities/resources and identify strengths and gaps. It assigns hospitals a score and position on a continuum of improvement, from “inadequate” to “advanced”.

Surveillance of HAI/Antibiotic Resistance

Surveillance of HAI and antibiotic resistance is the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and dissemination of data about HAIs and resistance to help guide clinical and public health decision-making and action. By providing baseline information on infection occurrence, it will help you develop benchmarks for infections in health care settings. It can also aid you in describing the microbiological profile of pathogens that cause HAIs. Surveillance can detect changes in endemicity of HAIs over time and detect hospital outbreaks. Use this surveillance data for research, to make decisions on policy and to set priorities and target activities. Surveillance can also be used to evaluate the impact of IPC measures and reinforce appropriate IPC and patient management practices.

Surveillance Resources

The WHO has invested a lot of efforts on supporting surveillance for antibiotic resistance. These resources are also listed in the Resources section.

- WHO Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS). GLASS promotes and supports a standardized approach to the collection, analysis and sharing of AMR data at a global level by encouraging and facilitating the establishment of national AMR surveillance systems that are capable of monitoring AMR trends and producing reliable and comparable data. More information is available in the Resources section.

- WHO Guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, Acinetobacter baumannii and Pseudomonas aeruginosa in health care facilities. These first-ever guidelines for the prevention and control of CRE, CRAB, and CRPsA in health care facilities include eight recommendations from experts and reviews of research. The guidelines are intended to support IPC improvement at the health care facility and national levels in both the public and private sectors, and include surveillance as well as monitoring, audits and feedback.

-

Antimicrobial Stewardship and Monitoring (5 min)

Antimicrobial stewardship plays an important role in preventing antibiotic resistance. It promotes appropriate actions for optimizing the use of antibiotics to improve the management of a patient or animal with an infection, while limiting harm. Antimicrobial stewardship also promotes sustainable access to effective therapy for all who need them.2 Think of this as the four Ds of optimal antibiotic therapy:

- the right Drug;

- the right Dose;

- De-escalation to pathogen-directed therapy; and

- the right Duration of therapy.

Antimicrobial stewardship is a team effort, so it is important to create an effective team. Most stewardship teams include an infectious disease physician or a pharmacist (or both), a microbiologist (or, as an alternative, working in collaboration with a microbiology laboratory), an infection prevention specialist (or IPC focal person), a hospital epidemiologist, someone from administration, and the clinician or prescriber. This list of members is the ideal; however, it may not always be possible in all settings. The main goal is to be sure that the treating team is advised by those with more specialized knowledge in treatment of infectious diseases and infection prevention.

Monitoring of Antibiotic Consumption

Surveillance of antibiotic consumption is an essential step in the antimicrobial stewardship strategy. In some countries, this type of surveillance is already mandatory.

For more information, see the WHO Report on Surveillance of Antibiotic Consumption and the Global Framework for Development & Stewardship to Combat Antimicrobial Resistance draft report in the Resources section.

-

Triage and Isolation (5 min)

Triage/Triaging

Another strategy to fight antibiotic resistance is patient triage. Triaging allows for early identification of potential high-risk patients (e.g., by using a triage risk assessment form) or previously known positive patients (e.g., by flagging a history of antibiotic resistance), based on patient history and/or signs and symptoms of infection. See the Resources section for a sample form you can use if your facility doesn’t already have one.

Once identified, the patient can be flagged, and the right precautions can be put in place according to risk assessment and known modes of transmission of the suspected or identified pathogen. A patient flag can be done either manually or electronically. This can involve either placing an alert sticker on the front of the patient’s notes, or an electronic alert that pops up when the patient is admitted. This alert should include the name(s) of the microorganism(s) present and indicate what precautions may be required. Be sure to use a system that all caretakers are familiar with so that everyone knows where to find this information.

Isolation and Cohorting

Isolation and cohorting are additional strategies to help curb the spread of antibiotic-resistant organisms from suspect or confirmed patients. These interventions should be considered as the next step once you identify patients during triage who are:

- known patients with recent history of antibiotic-resistant organisms; or

- suspected patients. In this case, take appropriate swabs and isolate or cohort the patient until microbiological culture results are available.

If no single isolation rooms are available, grouping patients together who are colonized or infected with the same organism (also called cohorting) can be considered. Cohorting confines their care to one area and prevents contact with other susceptible patients. Cohorts are created based on clinical diagnosis, microbiological confirmation (when available), epidemiology and mode of transmission of the infectious agent. When cohorting patients, follow these guidelines:3

- Have a dedicated area for patient beds, with at least one metre separating each bed from the next.

- Have dedicated staff to care for the patients.

- Restrict the number of visitors.

- Use single-use or disposable medical devices, if possible.

- Dedicate multiuse items (such as thermometers, stethoscopes, sphygmomanometers) to the isolation/cohorting environment.

- Decontaminate multiuse items and medical devices between patient use.

- Increase frequency of cleaning and/or disinfection.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Contact Precautions (10 min)

When caring for a patient with an antibiotic-resistant infection, you will need to use additional precautions; which precautions to be used will depend on the mode of transmission of the pathogen.

Modes of Transmission

Transmission-based precautions address infections caused by contact, droplet and airborne transmission. In this module, we will focus on contact transmission, which is the most frequent transmission mode of pathogens causing health care-associated infection (HAI), and the way high-priority resistant microbes are most commonly transmitted.

If you have taken the Introduction to IPC module or know basic microbiology, you should be able to answer the following questions on modes of transmission.

Contact Precautions

Standard precautions are used during routine patient care for all patients. The table below shows when you would use additional precautions.3 In this module, we will discuss contact precautions, since contact is the most frequent mode of HAI transmission.

Activity Standard Contact Hand hygiene x x Aseptic technique x x Decontamination of patient-care items and equipment x x Environment cleaning and disinfection x x Waste disposal x x Safe handling and transport of linens x x Patient isolation x In contact precautions, personal protective equipment (PPE) is meant to be an additional barrier, whereas in standard care PPE is worn according to specific indications.

PPE Standard Contact Gloves Only when likely to touch blood/body fluids and contaminated equipment and surfaces Upon entering room to provide patient care, when likely to touch blood/body fluids and contaminated equipment and surfaces Apron or gown Only during procedures likely to generate contamination from blood and body fluids (soiling) Upon entering room if clothing will have substantial contact with patient, surfaces or other items in room Face protection (surgical face mask) Only during procedures likely to generate aerosols* Only for situations that may provoke contamination of mucous membrane, i.e. mouth and nose, and procedures that are likely to create significant aerosols; suctioning, dentistry, intubation, chest physiotherapy, etc.Only during procedures likely to generate aerosols* Only for situations that may provoke contamination of mucous membrane, i.e. mouth and nose, and procedures that are likely to create significant aerosols; suctioning, dentistry, intubation, chest physiotherapy, etc.Eye protection/face shields Only during procedures likely to generate contamination with blood/body fluids Only during procedures likely to generate contamination with blood/body fluid Contact precautions include:

- ensuring appropriate patient placement, ideally in a single room with a dedicated toilet;

- using personal protective equipment (PPE), including gloves and gowns;

- limiting transport and movement of patients:

- using disposable or dedicated patient-care equipment, or, for multiuse items, decontaminating between patient use;

- prioritizing cleaning and disinfection of the rooms (i.e., increased cleaning frequency); and

- performing hand hygiene according to the 5 Moments, and before and after using PPE.

Click or tap the tabs to learn what PPE to wear when observing contact precautions.3

Gloves

Upon entering room to provide patient care, when likely to touch blood/body fluids and contaminated equipment and surfaces.

Apron/gown

Upon entering room if clothing will have substantial contact with patient, surfaces or other items in the room.

Face protection (surgical mask)

During procedures likely to generate aerosols, such as suctioning, dentistry, intubation, and chest physiotherapy.

Eye protection/face shields

During procedures likely to generate contamination with blood and body fluids.

You should also place signs on the doors of isolation rooms to alert staff and visitors to use contact precautions when caring for or visiting the patient. Sample signs are included in the Resources section.

For more information about contact precautions, see the CDC Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Healthcare Settings in the Resources section. (See also the Transmission-Based Precautions module.)

Patient Transfer

Limit movement and transfer of patients from the ward/room to essential purposes only. If you must transport a patient out of a room or ward, maintain IPC precautions to minimize risk of transmission of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Be sure to inform staff about IPC precautions. If you are transferring a patient to another health care facility, be sure that the receiving facility is informed about the patient’s infectious disease status and advise that the patient should be placed in isolation.

-

Hand Hygiene (5 min)

Hand hygiene is a key—if not the most important—measure to prevent the spread of infections, including those with antibiotic-resistant bacteria. It can be performed either by hand rubbing and hand washing. The former involves with the use of an alcohol-based handrub; the latter involves washing hands with plain or antimicrobial soap and water.

Hand Rubbing

Hand rubbing involves performing hand hygiene with an alcohol-based handrub, which is not only more effective, but also faster and better tolerated. After 15–30 seconds, hand rubbing is significantly more efficient than hand washing with plain soap and water at reducing bacterial contamination of the hands. The Resources section has a guide to local production of WHO-recommended hand rub formulations as well as the Guide to Implementation of the WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. (See also the Hand Hygiene module.)

Hand Washing Stations

To minimize risk of transmission, follow these best practices for hand wash stations:

- Use hand wash stations for hand washing only!

- Do not dispose of body fluids, beverages and foods in the hand wash basin – use dedicated (that is, dirty utility) area.

- Do not wash any patient equipment in hand wash basins or use basins for storing equipment awaiting decontamination.

- Ensure cleaning staff have been trained in correct cleaning procedures for taps and sinks, paying particular attention to limescale deposits.

- Identify and report any problems or concerns relating to safety, maintenance and cleanliness of hand wash stations to the IPC team and facilities department.

-

Environmental Cleaning & Medical Device Decontamination (10 min)

Environmental Cleaning

Why is a clean environment important in combating antibiotic resistance? To give you an idea of the importance of environmental cleaning, this table shows you how long microorganisms can survive outside the host.4

Microorganisms Survival time Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) 7 days to > 12 months Vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) 5 days to > 46 months C. difficile > 5 months Acinetobacter baumannii 3 days to 5 months E. coli 2 hours to 16 months Klebsiella spp. 2 hours to 30 months Norovirus 8 hours to 7 days4 If your environment is contaminated, there is a greater risk of spreading all types of infectious agents, including those resistant to antibiotics. Therefore, it is crucial to keep the environment clean, dry and dust-free.

When cleaning, always start with the clean area first and move to the dirtier areas, saving the dirtiest area for last. Clean top to bottom, in that order. Provide education and practical training to cleaning staff and make sure appropriate PPE is worn. Clean and disinfect all environmental surfaces, with special emphasis on frequently touched surfaces. Generally, floors should be cleaned with detergent. For some specialized areas, where there is higher risk (as a function of level of contamination and/or patient vulnerability to infection), after cleaning floors should also be disinfected.

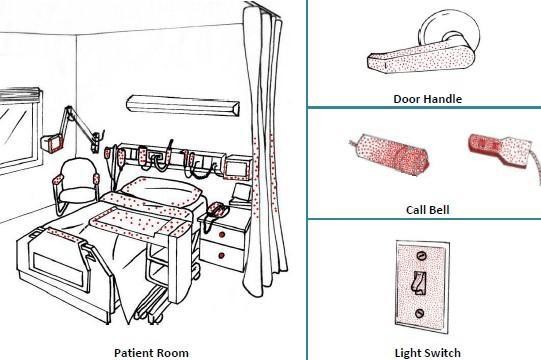

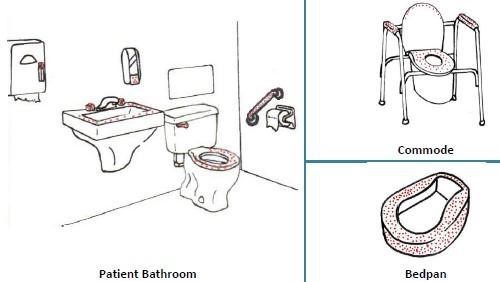

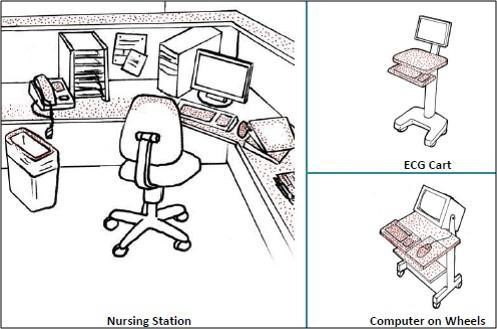

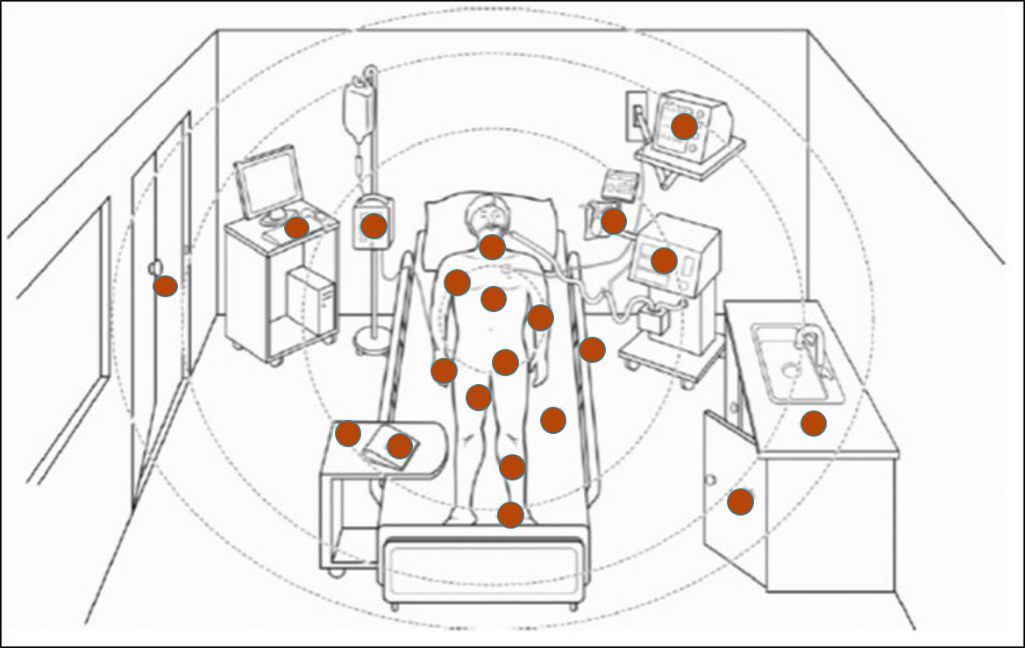

Examples of High-touch Items and Surfaces

It is important to understand that certain touch points in the hospital environment may be at higher risk than others. These are referred to as high-touch surfaces. The diagram below shows examples of common hospital items that are considered high touch. In the following illustrations, the red dots indicate areas of highest contamination and touch.

Sources: PIDAC: Best Practices for Environmental Cleaning for Prevention and Control of Infections: Ontario, 2012

Lin MY, et al. Crit Care Med. 2010; 38 (8):S335-344.

Decontamination

Decontamination of reusable medical devices is an important measure for preventing the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria. It is critical that any reusable device is safely reprocessed according to its classification and use.

The life-cycle of decontamination illustrates the relevant features of decontamination, with each step being as important as the next. This cycle represents each stage of the decontamination process, beginning from point of use or acquisition to decontamination followed by storage. This cycle is continuous and demands a minimum standard at every step to ensure safe reuse and handling of medical devices. Note that cleaning is important, as it is the basis for proper decontamination.

Watch this short animation on the decontamination life cycle.

For complete details and explanations on how to safely reprocess medical devices, please take the Decontamination training module.

-

Multimodal Strategies (20 min)

Using just one strategy for AMR prevention—for example, just training on contact precautions—is unlikely to be effective. Instead, WHO’s multimodal strategy for hand hygiene and IPC improvement are a way to integrate implementation in the local context, improve outcomes and change behaviour. Multimodal strategies also include bundles, which are structured tools for improving the care process and patient outcomes.

Scientific evidence and global experience show that each component of the WHO strategy is crucial. In general, no single component can be considered optional if the objective is to achieve an effective and sustainable impact. In practice, however, some components might be given more emphasis than others, depending on the local situation and available resources. Regular assessment allows health facilities to direct efforts to all, some or individual components at any given time.

In the Implementation Manual to Prevent and Control (found in the Resources section of this course) Carbapenem-resistant Organisms at the National and Health Care Facility Level, there are practical suggestions for implementing targeted interventions while applying the WHO multimodal strategy. This practical manual is designed to support national IPC programmes and health care facilities to achieve effective implementation of the WHO guidelines for the prevention and control of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, A. baumannii and P. aeruginosa in health care facilities. The principles and guidance provided in this manual are valid for any country and include a special focus on settings with limited resources.

Below are some recommendations from the manual. For each recommendation, think about what activities you could do to implement it at your facility.

Contact Precautions, Including Hand Hygiene and Isolation

Recommendation 2: importance of hand hygiene compliance for the control of CRE-CRAB-CRPsA: Hand hygiene best practices according to the WHO guidelines on hand hygiene in health care should be implemented. (Strong recommendation)

Recommendation 4: contact precautions: Contact precautions should be implemented when providing care for patients colonized or infected with CRE-CRAB-CRPsA. (Strong recommendation)

Recommendation 5: patient isolation: Patients colonized or infected with CRE-CRAB-CRPsA should be physically separated from non-colonized or noninfected patients using (a) single room isolation or (b) by cohorting patients with the same resistant pathogen. (Strong recommendation)

Multimodal strategies for implementing the recommendations listed above.

Build it The infrastructure, equipment, supplies, and other resources (including human) required to implement the intervention.

- Put in place/improve a sustainable system to reliably procure and deliver necessary supplies needed to enable: (a) compliance with hand hygiene at the ‘Five Moments’, that is, alcohol-based handrub at the point of care, water, soap and hand drying materials; (b) compliance with recommended contact precautions, that is, PPE, with a focus on the need for a range of sizes.

- In settings where water access/quality are not readily available, develop a plan for improving water access and quality.

- In settings where bar soaps are used for handwashing, they should be kept dry; hand drying materials should be single use.

- Develop/adapt enforceable protocols/standard operating protocols available at the point of care on: (a) who decides about patient isolation (that is, designate nurses as decision-makers on isolation as they are 24/7 on the wards and it can be done in a more timely manner; (b) which organisms require the implementation of contact precautions and isolation; (c) criteria for ward closure, for example, outbreaks; (d) when is it acceptable to care for patients with different CROs in the same cohort and how the geographical separation should be done (that is, where there is no availability of separate rooms and influenced by local epidemiology); (e) what supplies need to be procured and distributed regularly.

- Define and agree on roles and responsibilities for effective procurement systems with strong IPC involvement.

- In settings where single rooms are in short supply/unavailable, consider using coloured tape on the floor to reinforce contact precautions and the geographical separation of cohorted patients.

Teach it Training the appropriate health staff to ensure that interventions are implemented in line with evidence-based policies.

- Assess local training needs.

- Put in place/improve a reliable mechanism for producing/using updated training resources and information for staff on these recommendations with a focus on: (a) the use of risk assessment; (b) practical hands-on/real-life demonstrations (for example, PPE use); (c) training materials in the local language.

- Reinforce application of the ‘Five Moments’ for hand hygiene for patients with invasive devices.

- Ensure that senior management and hospital administrators fully understand all aspects of CROs, including the importance of the moments for hand hygiene, the use of PPE, and the indications for contact precautions and isolation.

- Secure sign-off of training plans by senior managers (for example, by the IPC committee or equivalent)

- Train staff on a regular schedule on all aspects of these recommendations (focus on pre-employment/orientation and periodic updates) and enable staff to train others.

- Develop information/educational resources using a range of media for patients and carers with a focus on the implications of infection/colonization and psychological support.

- Those performing training should be competent in the subject matter.

Check it Identifying gaps in IPC practices or other indicators to prioritize interventions and tracking practices to ensure that they are being done appropriately. Giving feedback to target audience and managers.

- Put in place/improve a monitoring, reporting and feedback mechanism (including roles and responsibilities) regarding:

- reliable availability of hand hygiene infrastructures and products, for example, clinical handwash basins, soap, water, hand drying products, alcohol-based handrub;

- percentage of staff compliant with standard operating procedures/protocols, for example, hand hygiene compliance according to the ‘Five Moments’; (b) use of contact precautions, including a mechanism for reporting shortages, stockouts and failure of PPE;

- reliable availability of isolation and cohorting facilities;

- appropriate use of isolation and cohorting facilities;

- availability and use of patient and visitor information materials;

- correct and timely implementation of contact precautions and isolation or cohort (that is, isolation of all patients with positive results for CRO in the last 24 hours).

- Ensure that monitoring, reporting and feedback mechanism address decision makers in addition to health care workers.

- Consider the development/use of daily/weekly checklists.

Sell it Promoting interventions, including through promotional and advocacy messages and materials.

- In collaboration with staff, develop/adapt:

- bedside identification reminders that respect the patient’s rights to privacy and dignity;

- awareness-raising messages (for example, posters) placed appropriately to remind staff of correct practices;

- scripts/prompts for local champions to use when communicating on necessary IPC measures for CROs (for example, strict use of contact precautions);

- memos (electronic/paper) to communicate rapidly and on a large scale, for example, during outbreaks;

- videos on the appropriate use of PPE;

- patient information materials (leaflets and visual resources to account for low literacy).

- Support and strengthen communications between different team members (laboratory, microbiology, IPC, clinicians).

Live it Support for interventions at every level of the health system. For example, senior managers providing funding for equipment and other necessary resources and being champions and role models for IPC improvement.

- Encourage senior management to use relevant opportunities to explain that the facility is supportive of tackling AMR/CROs and to promote and reinforce protocols/standard operating procedures.

- Engage senior clinicians and nurses to explain to colleagues the importance of hand hygiene, contact precautions and isolation/cohorting.

- Identify champions to be role models for the correct use of PPE.

- Put in place visible signage showing key leader commitment to hand hygiene and contact precautions.

Environmental cleaning

Compliance with environmental cleaning protocols of the immediate surrounding area (that is, the “patient zone”) of patients colonized or infected with CRE-CRAB-CRPsA should be ensured. (Strong recommendation)

Surveillance cultures of the environment for CRE-CRAB-CRPsA colonization/contamination. (Conditional recommendation)

In the boxes below or on a piece of paper, list 2-3 ideas of how you might implement these recommendations for each multimodal strategy. Then tap the Compare answer button to see an expert’s response.

For more information on multimodal strategies, refer to the WHO Core Components and Multimodal Strategies module.

-

Implementing IPC Interventions (5 min)

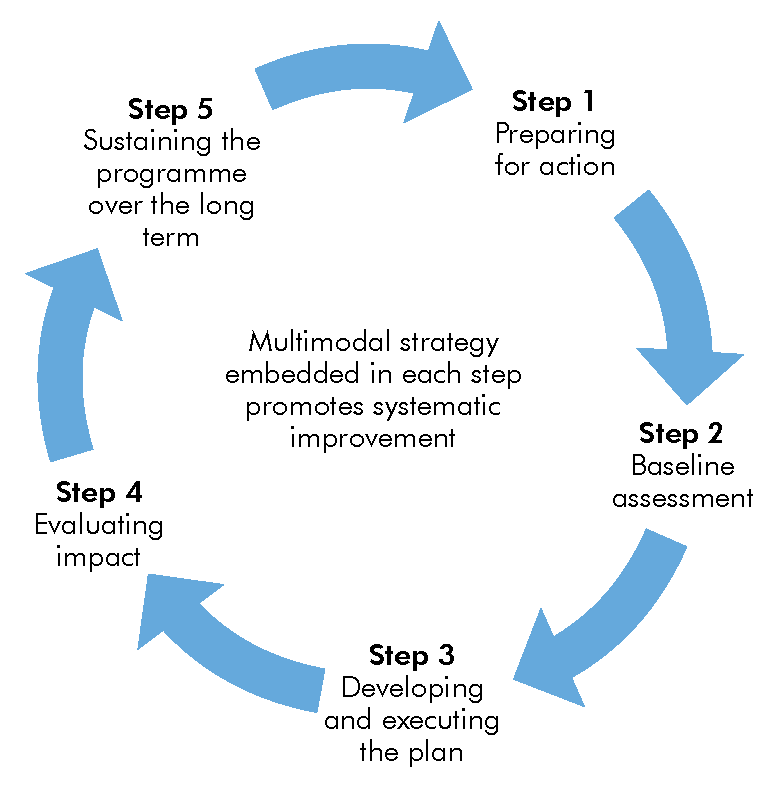

WHO has developed a five-step approach to support the implementation of IPC interventions. This approach is applied to carbapenem-resistant organisms (CRO) prevention strategies, which can be found in the Implementation Manual to Prevent and Control Carbapenem-resistant Organisms at the National and Health Care Facility Level (see resources). Click or tap on each step in the graphic to read more about how to implement IPC activities.

Step 1.

Prepare to start a programme of work or strengthen what is already in place to improve CRO prevention and control in the facility.

- This step involves a contextual reflection on the decision or need to invest in tackling this problem, identifying initial resources and conditions needed to support the successful implementation of future actions, and preparing to put them in place. (For example, consider supplies procurement and infrastructure issues, IPC programme organization, as well as any training required.).

- It also involves engaging senior management, key leaders and stakeholders in order to gather formal support to move forward with your plans—particularly in those clinical areas where CRO presents a current or potential problem. Selecting the personnel to be included in the team to drive forward the plans and convincing them to be involved will be critical. It implies the establishment of links with other key programmes/services (for example, the microbiology laboratory, the pharmacy or hospital engineers) to support the sustainability of efforts. Start small, where the burden is high and impact can be measured, and then build on early successes.

- Initial engagement, communications and advocacy need to be addressed as part of this step.

- Note: depending on the facility, this step can take months. However, it is important to note that during an outbreak situation, rapid action will be required within and beyond the stepwise approach presented here.

Step 2.

Conduct a baseline assessment of the current status of CRO spread and implementation of IPC recommendations for CROs in your facility.

- This involves focusing on the recommendation for monitoring/auditing and feedback (Recommendation 8) and assessing what is in place to enable implementation of all IPC recommendations for CROs. This evaluation could include the following actions:

- Conducting surveillance and/or gathering data about current levels of resistance and compliance with critical prevention practices/indicators. It is useful if data can be compiled by ward or hospital area. This forms an important part of baseline assessment.

- Reviewing data from existing surveillance and/or monitoring of HAIs and preventive measures related to CROs if already available—underpinned by a robust understanding of epidemiology (that is, infections imported or present on admission versus transmission during hospital stay). For example, it might be useful to undertake a retrospective exercise of reviewing existing microbiology data.

- Using the IPCAF or another relevant assessment tool evaluating the level of implementation of IPC in the facility (for example, water and sanitation for health facility improvement tool) assessment tools (13), with a focus on parts that reflect the key components for CRO prevention and control), such as section four of the IPCAF related to surveillance.

- A timeline for baseline assessment and reporting of results should be agreed upon. Importantly, determine who will receive the results and how they will be used to ensure the necessary action takes place.

- This step will clearly highlight strengths and weaknesses, and risks and needs, and thus is likely to highlight resource gaps that have not been addressed previously. In particular, it will facilitate an understanding of how these strengths and weaknesses pertain specifically to CRO transmission. (For example, if CRO surveillance is not in place and you have decided to undertake a point prevalence study, this step helps to evaluate the laboratory capacity for establishing ongoing surveillance, as well as the implications in terms of financial and human resources, equipment procurement, etc.).

- Highlighting existing strengths and achievements is important to convince decision-makers and other stakeholders that further success and progress is possible.

- Identifying particularly meaningful information or pieces of data will also help with engagement, communications and advocacy.

- Note: “assessment fatigue” is a real risk; creating ways to embed this work in existing activities/facility goals is important.

Step 3.

Act on the results of the baseline assessment.

- Develop and implement a plan of action informed by the results of your baseline assessment. Further discussion and consensus with key leaders and other stakeholders based on the baseline situation analysis may be necessary.

- A realistic, priority-driven action plan informed by the baseline assessment based on the local context is key.

- It is important to focus initially on achieving short-term wins. Some testing of the intervention plans may be useful at this stage.

- It is important to include responsibilities, timelines, budgets and expertise/other resources needed in the action plan, as well as review/reporting dates. Necessary resources may include personnel and/or relate to materials and equipment; many changes will involve process changes that affect current ways of working or the culture inside the organization.

- Anticipate risks or unintended consequences associated with this plan and identify mitigation measures (e.g., organizational implications of setting up patient isolation or cohorting, including exclusive staff dedication).

- Always seek approval for your action plan from key leaders and/or senior facility management to ensure buy-in and allocation of budgetary resources.

Step 4.

Collect evidence to determine what has worked and what gaps still remain, with the aim of measuring impact and engaging critical decision-makers.

- A follow-up assessment using the same tool used for baseline assessment will enable implementation progress to be tracked. This review should involve all key leaders, stakeholders, etc., identified in previous steps.

- Your action plan can be updated during this step. For example, update priority activities and revise roles and responsibilities. If possible, this should include a cost-effectiveness evaluation.

- A regular, realistic schedule of evaluation should be put in place—for example, using auditing methodologies.

Step 5.

Make local decisions on how prevention and control activities and improvements can be sustained; address ongoing gaps.

- This step is concerned with “routinizing” strategies for the prevention and control of CROs.

- This may require resources.

- It is important to build on experiences or lessons learnt, current understanding of the local situation, and organization of the overall IPC programme of work in order to ensure that IPC and CRO prevention is considered a critical part of the regular business of your health facility.

- This step would also include consideration of new actions required to counteract intervention fatigue; for example, launching a new campaign focusing on a certain aspect of CRO prevention.

- Be sure to build on the momentum of your work, celebrate success and maintain engagement!

- All key stakeholders will be critical in these discussions.

- Challenges associated with this step include turnover of senior managers and key leaders as they disengage, leave the facility, or move on to new projects.

- Remember to revisit all these steps systematically to keep focused on the ongoing improvement plans.

-

Knowledge Check (10 min)

-

Summary (5 min)

In these two AMR modules, you learnt about the burden AMR places on health systems. Having fewer drugs that can treat infections not only increases patient morbidity and mortality, but also has a high economic cost (including increased hospital stays, costs of diagnostic tests, and more expensive second-line antibiotics). You also learnt about risk factors that contribute to the emergence and spread of AMR, especially the overuse and misuse of antibiotics. WHO has developed the Global Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (GLASS) to promotes and supports a standardized approach to the collection, analysis and sharing of AMR data at a global level.

IPC plays a critical role to reduce both the spread of antibiotic resistant organisms and the occurrence of infection and thus, the need for antibiotic use with ultimate impact on AMR emergence. You learnt about various strategies to reduce and prevent the occurrence of AMR. The module covered horizontal and vertical interventions that you can use in your facilities. These strategies include

- conduct surveillance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, including screening of high-risk patients;

- antimicrobial stewardship and monitoring of antibiotic consumption;

- identification of high-risk patients;

- isolating or cohorting patients with known antibiotic-resistant infections;

- appropriate contact precautions;

- practicing hand hygiene and hand washing according to the 5 Moments;

- environmental cleaning and disinfection;

- decontamination of medical devices;

- train all health care workers on key IPC measure that stop the spread of AMR, and

- monitor infrastructure for IPC and IPC practices.

The modules ended with a discussion of the WHO multimodal strategy approach to implementing interventions to reduce AMR.

-

References

- Goal 6. Clean Water and Sanitation. UN Sustainable Development Goals

- Dyar, O. J., et al. (2017). "What is antimicrobial stewardship?" Clinical Microbiology and Infection 23(11): 793-798.

- Siegel JD, Rhinehart E, Jackson M, Chiarello L, Health Care Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. 2007 Guideline for Isolation Precautions: Preventing Transmission of Infectious Agents in Health Care Settings. Am J Infect Control. 2007 Dec;35(10 Suppl 2):S65–164.

- Dancer SJ. Controlling Hospital-Acquired Infection: Focus on the Role of the Environment and New Technologies for Decontamination. Clinical Microbiology Reviews 2014;27(4):665–690.