Prevention of Bloodstream Infections: Best Practices

In this module, you will learn about recommended best practices for insertion, maintenance, and removal of peripheral venous catheters (PVC) and central venous catheters (CVC). The module will also cover strategies to achieve effective implementation for prevention of bloodstream infections (BSI).

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- describe best practice for catheter insertion;

- describe best practice for catheter care and removal;

- describe approaches for conducting BSI surveillance;

- list prevention practices that help reduce BSI; and

- explain how multimodal strategies can effectively prevent infections associated with the use of peripheral and central venous catheters.

Learning Activities Estimated time:

-

Walid’s Story (5 min)

Thinking back to our previous case study, we now know that Walid is diagnosed with a laboratory-confirmed BSI. His medical team quickly prescribes the appropriate antibiotics and removes and reinserts a new central line. Walid stabilizes and becomes more and more independent during his stay in the coronary care unit (CCU).

After a week, Walid is discharged to the general cardiology ward. His central line remains in place in case it is needed again; although, it has been more than five days since it has been used. The nurse continues to provide appropriate daily maintenance.

-

PVC Insertion Best Practices (10 min)

In the previous module, you learned about the indications for appropriate catheter use. We will now move to the procedure for line insertion, beginning with peripheral venous catheters. Watch the video to learn how to insert a PVC line. The procedure in the video is the international standard that we aim to achieve. We should critically review our current procedure and see how we could improve our practice to offer the best and safest care possible to our patients.

Key points for safe PVC insertion- Ensure a clean work surface.

- Use required and sterile equipment.

- Perform appropriate hand hygiene.

- Confirm the identity of the patient and explain the procedure.

- Perform skin antisepsis.

- Use gloves only for the act of insertion.

- Use a non-touch technique for insertion.

- Dispose of the needle immediately after insertion.

- Choose an appropriate dressing.

Needle stick injuries are a very real concern in health care settings. Safely disposing of needles is a sure way to avoid injury and protect health care workers (HCWs). See the Injection Safety module for more information on best practices for disposing of needles. The Waste Management module has more information on how to safely treat sharps waste.

-

PVC Care & Maintenance (5 min)

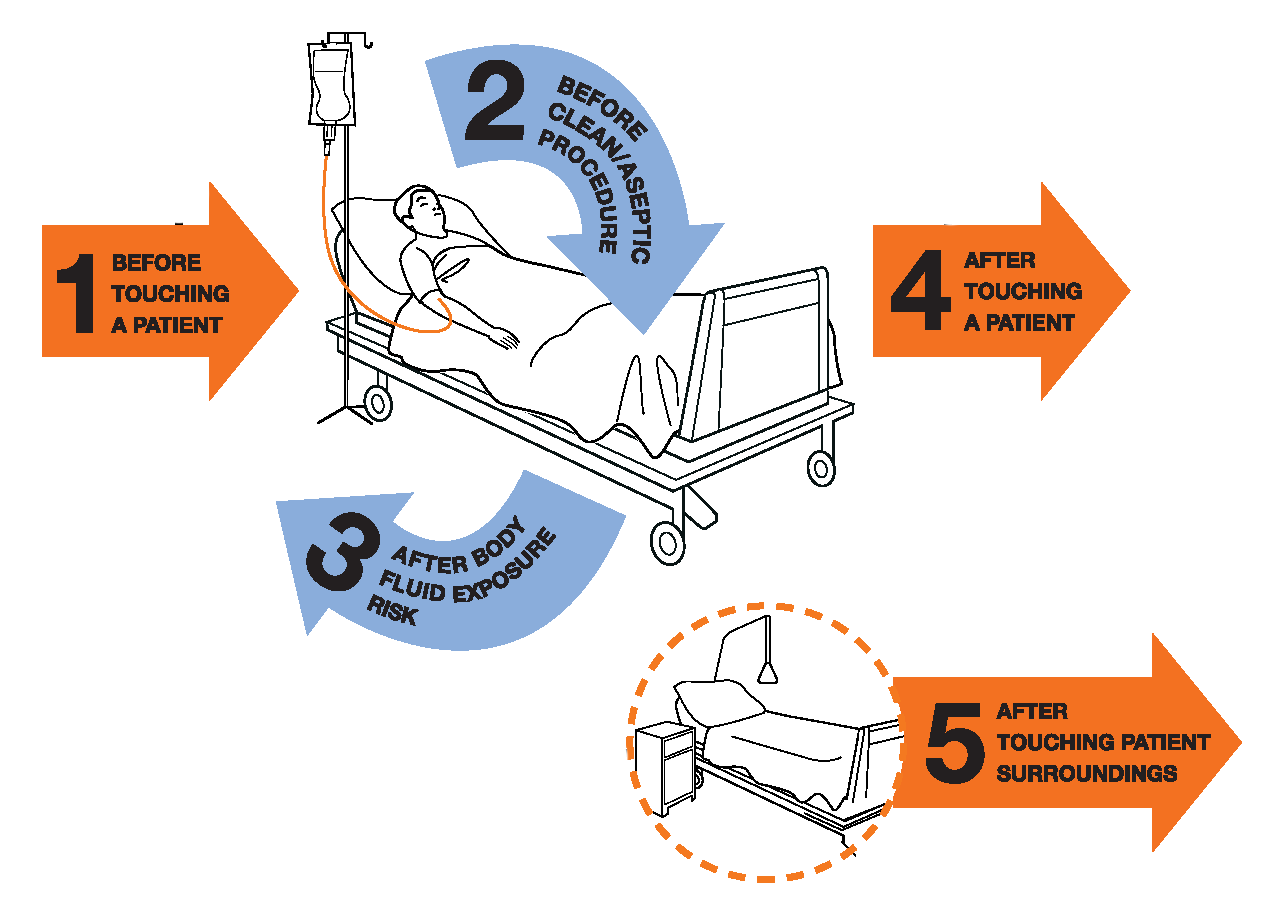

Now that you know about how to insert venous catheters, let us talk about catheter care and maintenance. Hands are often the primary way germs are introduced. It’s crucial that health care workers know when to perform hand hygiene at the right moment. To learn more on the WHO 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene when handling peripheral venous catheters, click or tap on the blue arrows in the graphic below, in particular, critical Moments 2 and 3.

Before cleaning/aseptic procedure

Immediately before any manipulation of the catheter and the associated intravenous medication administration system, such as:

- 2a. Catheter insertion or removal (before putting on clean, non-sterile gloves), dressing change, drawing blood or before preparing associated equipment for these procedures

- 2b. Accessing (opening) the administration set and infusion system

- 2c. Preparing medications for infusion into the catheter

After body fluid exposure

Immediately after any task that could involve body fluid exposure, such as:

- 3a. Inserting or removing the catheter

- 3b. Drawing blood

See the resources section for the 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene for Peripheral Venous Catheters and posters on Moments 2 and 3.

Take your best guess on the following questions.

Administration sets should be replaced immediately after using blood/blood products and within 24 hours after using lipids/parenteral nutrition. Otherwise, administration sets should be replaced no more frequently than 96 hours but at least every 7 days.1

When caring for patients with PVCs, be sure to document the following:

- date of insertion

- location

- reason for the vascular access

- appearance of the insertion site and dressing

- daily necessity.

A checklist (performed daily) can help HCWs to document if the catheter is still needed, when the administration sets were changed, when the dressing was changed, how the insertion site looks and if any complications have occurred.

-

CVC Insertion Best Practice (10 min)

Watch the video to learn how to insert a CVC line. The procedure in the video is the international standard that we aim to achieve. Not all health care settings might follow this exactly, but we should critically review our current procedure and see how we might improve our practice to offer the best and safest care possible to our patients.

Key points for safe CVC insertion- Ensure a clean work surface.

- Use a check list to ensure you have the required material for insertion.

- Prepare skin appropriately and using antisepsis.

- Take maximal sterile barrier precautions (sterile gloves, gown, and large drapes).

- Use the right technique of insertion (ultrasound guidance, if available).

- Fix the catheter (suture vs needless device).

- Dress the catheter with sterile dressing.

- Document the procedure in the chart.

-

CVC Care & Maintenance (5 min)

As with PVC care, a checklist can help to ensure the right information is documented. The checklist should include:

- whether the catheter is still needed;

- when the administration sets were last changed (72 hours–7 days; 24 hours for blood/lipids);

- when the dressing was last changed (this should be changed if the dressing shows leakage or is bloody or oozing);

- the state of the insertion site (this should be done daily); and

- if there are any complications.

Fundamentally, the main principles to ensure the best routine care for CVCs are:

- using a non-touch technique when accessing the catheter;

- disinfecting the needleless access devices;

- manipulating open hubs using gauze (either sterile or soaked in alcohol) and disinfecting the hub before injecting drugs; and

- preparing infusates using aseptic technique.

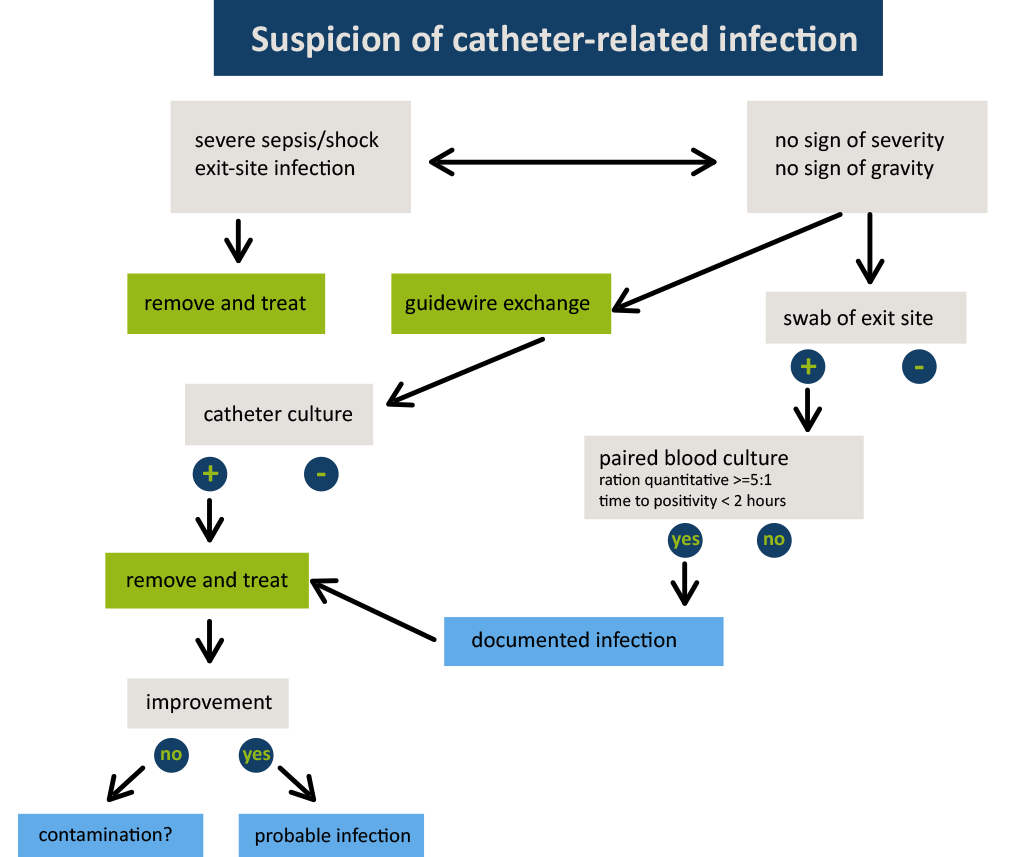

The facility should also have criteria for catheter removal. Whenever there is a malfunction, thrombosis or suspicion of infection, consider catheter removal.

Administration sets should be replaced immediately after using blood/blood products and within 24 hours after using lipids/parenteral nutrition. Otherwise, administration sets should be replaced no more frequently than 96 hours but at least every 7 days.

As a principle, central lines should not be placed over a guidewire. If, for any reason, this must be done, carefully follow the algorithm below.

If you change a CVC due to fever and a positive blood culture result comes back, you will need to change the CVC again and place it at another site.

-

Monitoring & Surveillance (5 min)

Having now covered the more clinical aspects, let us move onto monitoring and surveillance of CRBSI as it relates to both PVC and CVC. It is crucial to conduct surveillance to understand the burden of BSI in your facility, and any intervention should be accompanied by surveillance so that you can know if you are on track or if the intervention needs to be adapted. Additionally, it is critical to provide timely feedback to colleagues in order to motivate them and assist in changing their behaviour.

Monitoring

When auditing (or monitoring) PVC and CVC practices,

- perform regular audits on condition, indication, duration and documentation;

- perform competency assessments for catheter insertion or catheter manipulation; and

- give immediate feedback to the health care workers in charge of catheter care.

Performing bed-side audits on competencies with immediate feedback to the HCW has been shown to prevent infections.

PVC Surveillance

We cannot survey everything prospectively and in detail. There is a balance between resources and meaningful surveillance, which is particularly important for surveillance of infections due to venous catheters. There are two types of indicators you can use to help you focus your surveillance efforts: outcome indicators and process indicators. Click or tap on each tab to learn more about these two indicators.

Outcome

Let us first talk about using outcome indicators. Outcome indicators measure the endpoint or the result of care or performance, such as the number of patients with central line-associated BSI (CLABSI). In case you have very few infections, count days since last infection. Examples of outcome indicators include:

- CRBSI/CLABSI

- exit-site infections

- clinical sepsis.

Process

Outcome indicators are only one type of indicators used for monitoring and surveillance. Process indicators track enablers and key steps that result in changes in outcome. In some cases, it may be better to focus on process indicators, especially when the surveillance system is new. These indicators are easier to observe and the events to be measured are frequent, which means that change of practices over time is easily detected. Choose meaningful process indicators to track. Examples of process indicators for BSIs include:

- hand hygiene

- insertion checklist

- maintenance checklist

- catheter duration time.

Methods for infection surveillance

Although process indicators are very useful to track behavioural change, surveillance of infection (outcome) is the gold standard. One method is prospective surveillance. However, this method is cumbersome and resource intensive for tracking PVC-associated BSI, because all positive blood culture results must be checked and linked to a peripheral line. Therefore, this method is usually not recommended. It may, however, be recommended if you suspect or detect high levels of adverse outcomes in patients with PVCs. For CVC-associated/related BSI, prospective surveillance is the best method. The best denominator to estimate the risk is catheter-days because the infection risk increases with duration of indwelling catheter.

Data collectors go on ward rounds, interview clinicians and monitor current patient records to gather data about the endpoint or the result of care or performance. In this case, they would collect data on the number of patients with bloodstream infections or exit site infections.It will be difficult to reliably obtain data on catheter-days from peripheral lines if there is no electronic system at your facility. In this case, it is better to not collect this data if your facility does not have one. If the proportion of patients with a PVC in place is constant in your hospital, you can just count events; otherwise, count events and report per 1000 patient-days.

A less resource-intensive surveillance method for PVC-associated BSI would be to conduct prevalence surveys on appropriate use (number, indication, condition, dwell-time, documentation) of PVCs and to do a root-cause analysis of severe PVC-associated bloodstream infections.

In prevalence surveillance, surveys are conducted on a single day/week. While this type of surveillance provides data only at the time it was conducted, it can be repeated at regular intervals to show change. Prevalence is the proportion of people in a population who has a disease at one point in time.

Calculation:

new and existing events population at a point in time

Example:

number of patients with BSI all patients with PVCs on June 30Also known as a cause and effect or fishbone analysis. This is a way for people to explore the underlying causes of problems.The table below shows the recommended approach to reporting infection rates according to catheter type.

PVC CVC How to measure? CRBSI per 1000 patient-days CRBSI per 1000 catheter-days Alternative way to measure? Clinical sepsis or exit site infections per 1000 patient-days Clinical sepsis or exit site infections per 1000 catheter-days How to track Audits: repeated prevalence survey of PVC use Audits Feedback

Feedback to health care workers is an integral part of surveillance. Share the impact of BSI on mortality, disability and costs with decision makers, such as heads of departments, chief doctors or head nurses and senior managers. Make sure timely feedback is given directly to frontline workers because often they never see the data.

To learn more about conducting surveillance, take the Health care-Associated Infection (HAI) Surveillance module.

-

Preventing BSI (5 min)

As mentioned in the first BSI module, although BSIs are a small percentage of all HAIs, they represent a significant cost and burden on patients and hospitals. Therefore, preventing BSIs should be a crucial part of your IPC programme.

Take a few minutes to reflect on the questions below. You can type in your responses in the boxes below or just think about the answers.

- Does your hospital need a strategy to improve PVC or CVs use? If yes, what strategy and components would you use?

- What are the barriers you anticipate?

- What could be the facilitators?

Using a multimodal strategy

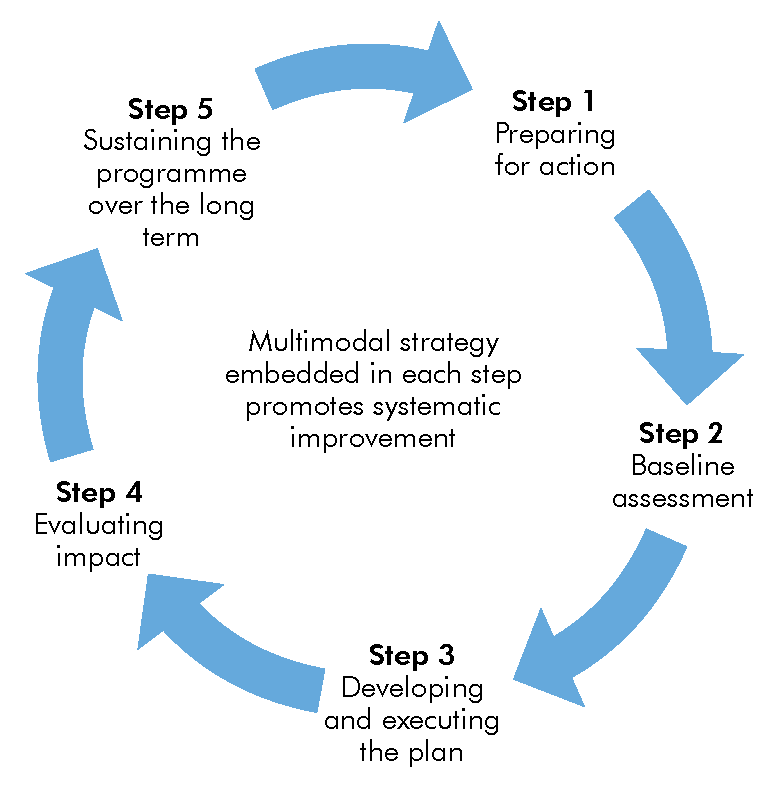

When planning BSI prevention interventions, WHO recommends using a multimodal strategy, which is a combination of several approaches or strategies.

Some examples of a successful strategy would include a combination of:

- availability of appropriate supplies and equipment for ensuring safe line insertions organised appropriately in a clean dedicated cart for catheter insertion (build it);

- education and training including both theoretical and practical sessions in small groups (teach it);

- prospective surveillance and feedback (check it);

- promotion of best practices, through the use of checklists, reminders (sell it); and

- role models championing best practices and key messages (live it).

The Core Components and Multimodal Strategies module has more information about this topic.

Using technical and adaptive approaches

Evidence-based IPC technical interventions to improve IPC practices are most successful when implemented within an enabling environment supportive of a patient safety culture and people-centred service delivery, including patient participation (i.e., an adaptive approach). Combining technical work with adaptive work is essential in our implementation strategies. Using both approaches will help us support staff to consistently perform tasks the right way and will ensure that safe practices become the "norm”.

The intangible work that shapes the attitudes, beliefs, and values of clinicians towards a safety culture.Designing interventions

In order to carefully use your resources, you may wish to plan a stepwise intervention to bring down infections. Breaking down a complex intervention to manageable parts also helps in the implementation process and supports sustainability.

Here is an example. A quasi-experimental study (2004-2011)2 was conducted to evaluate an intervention to reduce peripheral vein phlebitis (PVP) and PVC-related bloodstream infections (BSIs). The bundle intervention consisted of health care worker education and training (teach it), withdrawal of unnecessary catheters, exchange catheter policy (build it), withdrawal of catheters at early stages of PVP, use of scales as a measuring tool (check it), and repeated period-prevalence surveillance of PVC adverse events on wards (check it). The researchers found that PVP decreased by 48% during the intervention period versus 23.3% in pre-intervention period. A significant incidence reduction in PVC-related BSIs and health care-acquired S. aureus BSIs was also achieved.

According to the Institute for Healthcare Improvement, “a bundle is a structured way of improving the processes of care and patient outcomes: a small, straightforward set of evidence-based practices—generally three to five—that, when performed collectively and reliably, have been proven to improve patient outcomes.”Click or tap on each step in the graphic to read about the activities associated with that step.

Step 1

Step 1 is the preparatory phase. In this step, start to think about the context, the intervention or innovation that you want to change—in this case, prevention of infection associated with vascular catheter (central and/or peripheral) and the recipients of the intervention. Carefully select who will help design or support the intervention and be sure to involve all stakeholders early in implementation process (multidisciplinary/multi-professional).

Step 2

As you move to step 2, use available tools to perform a baseline assessment, which can provide rich and vital information on the current situation about the local epidemiology of these infections, practices in place and compliance with the gold standard. It will reinforce your initial thinking on the context for change, provide insights on the challenges and barriers to implementation and provide some information on recipients. Baseline assessment is a critical step in how to design and execute your intervention plans.

Step 3

In step 3, you will develop your plan, informed by the intelligence gathered so far. In this step, drill down and consider each of the elements of the multimodal strategy. These elements include:

- identifying what is needed to build the best supportive systems for change;

- using the most appropriate teaching approaches;

- agreeing upon how to check whether a change has taken place and practice is improved;

- choosing which methods to sell the intervention and communicate to key players; and

- identifying how you will secure the necessary institutional support towards creating a culture that values the change in practice and patient safety.

Make sure the intervention is clear, detailed and adapted to the context (i.e., based on capacity of professionals).

Step 4

Step 4 involves repeating an assessment of the overall impact of the intervention.

Step 5

In step 5, review your approach and plans to determine how to sustain the change.

-

Case Study (10 min)

Background

A study3 was done on the extent to which CRBSIs could be reduced in Michigan, United States, using an intervention as part of a statewide safety initiative on intensive care unit (ICU) patients. The objective of the study was to evaluate the effect of the intervention up to 18 months after its implementation.

Between March 2004 and September 2005, participating ICUs implemented several patient-safety interventions and monitored the effect of these interventions on specific safety measures. These included:

- An intervention to reduce the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection

- A daily goals sheet to improve clinician-to-clinician communication within the ICU

- An intervention to reduce the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia

- A comprehensive unit-based safety program to improve the safety culture.

Hospitals started with implementation of the unit-based safety program and use of the daily goals sheet and then, in any order, implemented the other two interventions during the subsequent six months.

The ICUs were asked to designate at least one physician and one nurse as team leaders. The team leaders were instructed in the science of safety and in the interventions and then disseminated this information among their colleagues. Training of the team leaders was accomplished through conference calls every other week, coaching by research staff, and statewide meetings twice a year. The teams received supporting information on the efficacy of each component of the intervention, suggestions for implementing it, and instruction in methods of data collection.

Team leaders were partnered with their local hospital-based infection-control practitioners to assist in the implementation of the intervention and to obtain data on catheter-related bloodstream infections at the hospital.

The study intervention targeted clinicians’ use of five evidence-based procedures recommended by the CDC and identified as having the greatest effect on the rate of catheter-related bloodstream infection and the lowest barriers to implementation.4 The recommended procedures are hand washing, using full-barrier precautions during the insertion of central venous catheters, cleaning the skin with chlorhexidine, avoiding the femoral site if possible, and removing unnecessary catheters.

Strategies to increase the use of these procedures included:

- clinicians were educated about practices to control infection and harm resulting from catheter-related bloodstream infections

- a central-line cart with necessary supplies was created

- a checklist was used to ensure adherence to infection-control practices

- providers were stopped (in nonemergency situations) if these practices were not being followed

- the removal of catheters was discussed at daily rounds, and

- the teams received feedback regarding the number and rates of catheter-related bloodstream infection at monthly and quarterly meetings, respectively.

The effect of this intervention on CLABSI reduction was not only demonstrated in the short- and medium-term, but it was also shown to last up to 10 years in 73 hospitals in Michigan.5 Furthermore, it was adopted by other countries. The approach used in this study fits very well into the framework of the WHO multimodal improvement strategy for implementing IPC interventions including the prevention of catheter-associated BSI. Indeed, the various components of the intervention clearly match the elements of the WHO strategy.

-

Summary (5 min)

You learned about the best practices for inserting and removing PVCs and CVCs. You also learned about care and maintenance of peripheral and central lines. Performing hand hygiene is crucial when manipulating PVCs and CVCs. Be sure to review Moments 2 and 3 in the 5 Moments of Hand Hygiene for PVCs and CVCs.

The module also covered the importance of monitoring and surveillance to help reduce BSI rates at your facilities. Conducting surveillance on intervention activities will help you know if you are on track or if the intervention needs to be adapted. You can also use monitoring and surveillance to provide feedback to staff so that they can change their IPC practices.

Finally, you learned about how multimodal strategies can effectively prevent infections associated with the use of peripheral and central venous catheters.

-

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guidelines for the Prevention of Intravascular Catheter-Related Infections, 2011.

- Mestre G, Berbel C, Tortajada P, Alarcia M, Coca R, Fernandez, MM, et al. Successful multifaceted intervention aimed to reduce short peripheral venous catheter-related adverse events: a quasiexperimental cohort study. Am J Infect Control. 2013 Jun;41(6):520-6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2012.07.014. Epub 2012 Oct 16.

- Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, Sinopoli D, Chu H, Cosgrove S, et al. An Intervention to Decrease Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2725-32.

- Mermel LA. Prevention of intravascular catheter-related infections. Ann Intern Med 2000;132:391-402.

- Pronovost PJ, Watson SR, Goeschel CA, Hyzy RC, Berenholtz SM. Sustaining Reductions in Central Line-Associated Bloodstream Infections in Michigan Intensive Care Units: A 10-Year Analysis. Am J Med Qual. 2016 May;31(3):197-202. doi: 10.1177/1062860614568647. Epub 2015 Jan 21.