Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections: Overview

Catheter-associated Urinary Tract Infections (CAUTI) are one of the most common health care-associated infections (HAIs). These infections are most likely caused by bacteria entering the body during catheter insertion, as a result of prolonged or unnecessary use of urinary catheters, or due to a disruption in the closed drainage system. CAUTI, like many HAIs, can be prevented. In this module you will learn about CAUTI incidence, causes, risks and proper indications for using a urinary catheter.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- describe the global burden of CAUTI in relation to HAI with a focus on low- and middle-income countries (LMIC);

- describe how microbes can enter the urinary tract and cause infection;

- identify the risk of CAUTI in health care facilities;

- explain appropriate and inappropriate indications for catheter use; and

- apply proper practices for catheter insertion and management to prevent/avoid CAUTI, including implementation of multimodal improvement strategies.

Learning Activities

-

CAUTI in India (15 min)

The Udaipur Central Health Centre is a community health centre (CHC), meaning they serve a larger population than most rural health facilities. The facility is equipped with 30 beds and has some lab capacities. The infection prevention and control (IPC) team of a tertiary health facility in rural Delhi conducts a bi-monthly meeting with facility management to discuss pertinent issues and possible solutions. This month, as a result of an increase in CAUTI rates, the IPC team has decided to focus on the greater frequency of urinary catheter use in Udaipur compared to other areas of India. For instance, reports from Tamil Nadu suggest much lower use of urinary catheters. Tamil Nadu has been a model for health care improvements in India. The IPC team hopes to use this exploratory work to improve patient outcomes.

Surveys about CAUTI prevention were conducted among a cross-section of relevant staff. The results indicated that a low number of facility staff had knowledge of CAUTI prevention practices, with gaps in knowledge of when to insert a catheter. This, coupled with staff absenteeism, raised alarm bells for the IPC team.

The team will be meeting with facility management to present their findings, with the hopes that management will approve a budget to address the problem. The team and facility management will meet again later in the month to discuss possible solutions.

Imagine you are a member of the IPC team. In either a notebook or the text box below, make a list of the information you would gather to present to facility management. Click or tap the “Compare Answer” button below to learn what the IPC team came up with.

-

Avoiding CAUTI (10 min)

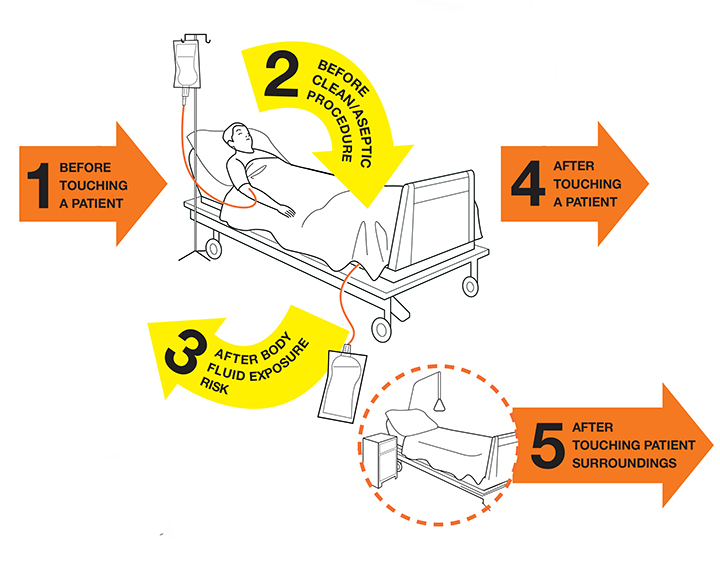

There are a few key strategies you can implement in your facility to prevent CAUTI. Hand hygiene is one important part of CAUTI prevention. Observe the 5 Moments of Hand Hygiene, paying particular attention to moments 2 and 3.1 Click or tap the yellow arrows below to read more about how proper hand hygiene can prevent infections associated with catheter use.

Here is a summary of the key considerations for avoiding CAUTI in a patient with a urinary catheter.2

Moment 2

Immediately before any manipulation of the urinary catheter or drainage system that could lead to contamination of the sterile urine, such as:

- inserting or applying an indwelling, intermittent straight, or condom catheter, and immediately before putting on sterile gloves; and/or

- accessing the drainage system to collect a urine sample or empty the drainage bag.

Why? To protect the patient against harmful germs, including the patient’s own, from entering his/her body.

Moment 3

Immediately after any task involving the urinary catheter or drainage system that could lead to urine exposure, such as:

- collecting a urine sample;

- emptying the drainage bag; and/or

- removing the urinary catheter.

Why? To protect yourself and the health care environment from harmful patient germs.

Insertion

- Avoid urinary catheterization if possible.

- Hand hygiene is critical (especially moment 2 before an aseptic/clean procedure, and moment 3 after blood and body fluid exposure).

- When feasible, use a two-person team to insert the catheter.

- Use sterile equipment and aseptic technique during both insertion and after-care/maintenance.

Maintenance

- Review the need for the catheter daily; when no longer needed, remove as soon as possible (ideally within 48 hours).

- Maintain closed drainage.

- Empty the drainage bag regularly into a clean receptacle used only for that patient.

- The receptacle should be changed daily.

- Do not change the catheter routinely if it is functioning properly.

- Do not use bladder irrigation/washout and antiseptics/antimicrobial agents. They do not prevent CAUTI.

We will explore these more in depth later in the module. Before that, we will look at the burden and problem of CAUTI globally.

-

Epidemiology of CAUTI in LMIC (15 min)

In order to communicate the precautions necessary to lower the risk of CAUTI in your facility, it is important that you understand both its local (if available) and global incidence and impact. Consider how incidence and impact affect your facility when discussing CAUTI solutions with your IPC team.

Incidence

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) account for up to 40% of all HAIs.2 CAUTI is a type of UTI caused by a combination of patient, health worker and system-related factors that we will cover in this module. Indwelling urethral catheter use is thought to be responsible for 70–80% of UTIs, and is a major cause of bloodstream infection and sepsis. The occurrence of CAUTI is much higher in LMICs than in high-income countries. The risk of a patient developing a CAUTI increases by 3–7% each day the catheter remains in the patient.2

The good news is that 65–70% of CAUTI are preventable.3 This means that you can put measures in place that prevent CAUTI from occurring in patients. Over the course of this module you will be introduced to methods and strategies that will strengthen your capacity to prevent these infections and keep patients safe.

Impact

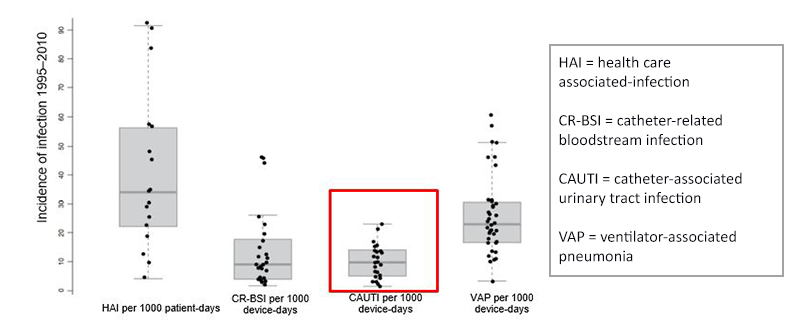

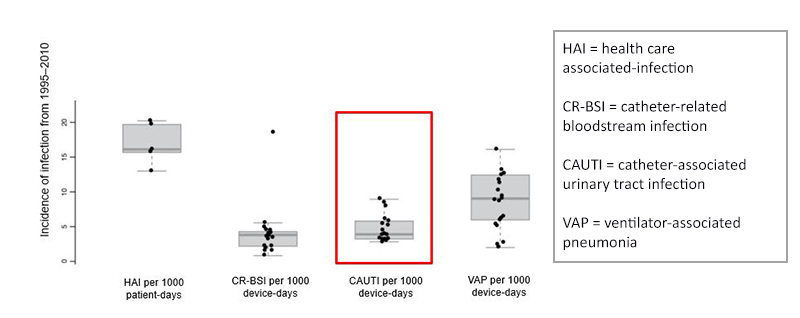

The unfortunate truth is that, like other HAIs, the risk of CAUTI is higher in LMIC settings, especially among high-risk patients. In general, more patients develop HAIs, particularly those associated with invasive devices, in LMICs than in high-income countries. Those most at risk are more likely to be the most vulnerable patients—for example, those in intensive care units (ICUs), or immunosuppressed patients. The following graph shows the incidence of all HAIs, and of HAIs associated with invasive devices (like the urinary catheter), among high-risk patients in LMICs. HAI incidence density in these settings varies significantly, between 4.1 and 91.7 episodes per 1000 patient-days.4, 17

Patient-days are a standard denominator used to define how many patients are at risk of developing an HAI. For example, one patient in an ICU for seven days represents seven patient-days. In this example, this would mean 4.1 to 91.7 episodes of infections associated with various invasive devices occur for every 1000 patients admitted with an invasive device.

Take a look at the average cumulative incidence of CAUTI among adult ICU patients: 8.8 per 1000 urinary catheter-days.4, 17

Urinary catheter days is a denominator used to define the number of patients at risk of developing a CAUTI. In other words, it is the number of patients with an indwelling urinary catheter. For example, if a patient has a catheter in place for seven days, this represents seven urinary catheter days.

In high-income countries, the HAI incidence density range is lower overall (13.0–20.3 episodes per 1000 patient-days, versus 4.1–91.7 per 1000 patient-days in LMICs).4, 17 As you can see, these graphs also indicate that the incidence of CAUTI in LMICs is twice as high as that reported in high-income countries. It is important to note that, although it may look as though the rates on the first graph were lower than rates in the second graph, this is not the case. Instead, it is simply due to the different y-axis ranges. The bottom line here is that the reported incidence of CAUTI, while not the most common HAI, is a significant cause of harm to patients (e.g., causing bloodstream infections and sepsis).4, 17

Complications

Take a moment to think about catheter use in your facility. In a notebook, or in the text box below, list three or four complications that can occur that may impact both on patients and the health care facility. Click or tap the Compare Answer button below to read an expert’s response.

With some understanding of incidence, prevalence and impact, including complications to the patient, the next activity will describe the routes that microorganisms use to enter the body while the urinary catheter is in place.

-

Routes of Entry of Uropathogens (10 min)

When considering the factors that influence whether a patient develops CAUTI, it is helpful to understand how the different microbes that can cause CAUTI (uropathogens) can enter the body (i.e., their routes of entry). Uropathogens can enter the body when a foreign device (such as a urinary catheter) is inserted into a patient’s urethra. While the bladder is usually sterile, the catheter tube provides a way for these bacteria to enter the body and potentially cause infection. We will learn more about the different types of uropathogens in a later activity.

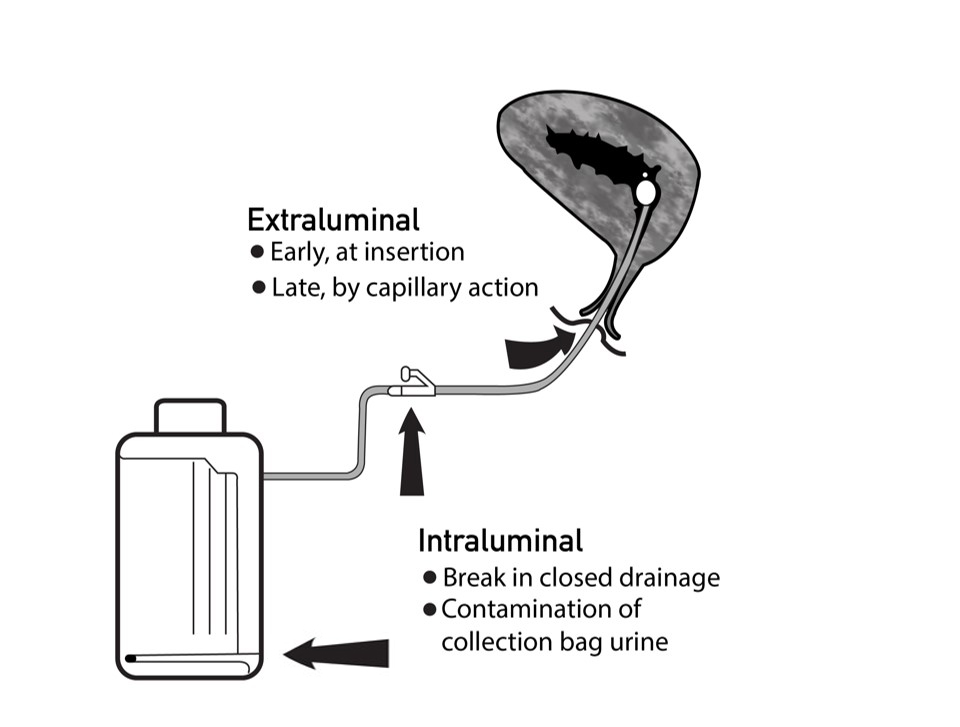

Routes of Entry

There are two ways through which bacteria can enter the body (routes of entry) via the urinary catheter. Potentially harmful bacteria may enter the bladder by either extraluminal or intraluminal routes. The extraluminal route refers to the outside of the catheter—i.e., between the catheter and the uroepithelial surface. The intraluminal route refers to bacteria entering through the inside of the catheter—e.g., when there is a break in the closed drainage system and/or when asepsis is defective. This can occur during specimen collection or when the bag is disconnected.2,7

urethral surfaceCAUTI may either be endogenous (occurring via meatal, rectal, or vaginal colonization) or exogenous (occurring via contamination from equipment or contact with the hands of an HCW).

There are several possible risks that can occur as a result of urinary catheterization, because they increase the likelihood of infection:7

- disruption to natural mechanisms for protection against infection, such as urine flow;

- damage occurring when inserting a catheter, exposing the urinary tract to colonization and infection;

- damage to the urethral lining (uroepithelial mucosa), making it easier for bacteria to stick to the surface of the urethra;

- incomplete voiding of urine from the bladder due to the presence of the catheter balloon, providing a medium for bacterial growth; and

- reflux of contaminated urine from the collection bag.

urethral liningBeing aware of these risks will help you to prevent CAUTI infection in your facility. You will learn about the proper procedure (aseptic technique) for both female and male patients in the following module, CAUTI Prevention.

-

Risk Factors for CAUTI (10 min)

Because there are many risks associated with the use of catheters, avoiding them when possible or reducing the amount of time they are placed in patients is critical to preventing CAUTI. In fact, the key risk factor is the length of time a catheter is in place. Above all else—unnecessary catheter placement should be reduced, and duration of placement minimized.

Click or tap the tabs below to read more about which patients are at risk of CAUTI, how HCWs contribute to CAUTI risks, and how factors within the health system can affect CAUTI risks.

Patient-related

Patient-related risk factors that increase the risk of CAUTI include:8,9,10

- pregnancy or other factors that alter patient physiology;

- impaired immunity, such as diabetes, HIV, and chemotherapy;

- severity of illness, or the presence of other infections;

- female sex (due to the shorter length of the urethra);

- patients over the age of 50;

- malnutrition or dehydration; and

- faecal incontinence or incomplete emptying of bladder.

HCW-related

HCWs play a key role in decisions relating to catheter insertion and removal, and are responsible for adhering to the correct techniques associated with insertion and maintenance. HCW-related risk factors that increase the risk of CAUTI include:8,9,11,12

- inappropriate use and/or overuse of catheters (e.g., for collecting specimens, or for the convenience of the nursing staff);

- lack of asepsis during insertion and maintenance, including defective hand hygiene at moments 2 (before aseptic technique) and 3 (after bodily fluid exposure risk);

- lack of documentation and record-keeping, including the lack of a review and removal plan, or no routine checks;

- emptying collection bags from multiple patients into one container (germs can backtrack, causing cross-infection);

- positioning the urine bag and/or drainage tube incorrectly: positioning the bag on the floor could expose the bag to possible microbes on the floor, whereas positioning the bag above the bladder causes backflushing;

- putting antiseptic solution into the collection bag;

- flushing the catheter routinely;

- not using sampling ports for urine specimen collection; and

- contamination while disconnecting the drainage system due to not adhering to asepsis.

System-related

Effective prevention of CAUTI depends on a health care environment and system that is supportive of the right practices and enables HCWs to perform their tasks correctly. Ask yourself these questions about your facility:8,11,12

- Do I have the right equipment and infrastructure to enable me to perform urinary catheterizations safely? For example:

- Is there access to urinary catheters (sterile) of varying sizes and types?

- Is there access to other resources that support insertion and maintenance—e.g., catheter securing devices, lubricating gel (single- or multiuse), gloves, hand hygiene materials, urinals, bedpans?

- Are there enough HCWs in the facility?

- Are guidelines, policies and procedures readily available to support HCWs?

- Are training and education on CAUTI prevention in place?

- Is catheter insertion and maintenance monitored? Is regular feedback provided?

- Are urinary catheters removed safely, and when indicated?

- Is there a culture of safety that supports CAUTI prevention?

-

Biofilms, Microorganisms and CAUTI (10 min)

Watch this video about how biofilms form and cause bladder infection.

Biofilms

As you saw in the video, biofilms are clusters of bacteria held together by an extracellular polymeric matrix. Biofilms form in aqueous environments, so the internal and external surfaces of a catheter are likely surfaces for biofilms to form. They form shortly after insertion, and can ascend to the bladder within one to three days. Shedding of bacterial cells from the biofilms can lead to infection. Some biofilms block catheters, which can lead to kidney or bladder stones. Biofilms can stop antimicrobial agents from reaching their target, meaning that antibiotics may not work, and treatment failure can occur.

A matrix of substances produced by microbes that help a biofilm to develop.Microorganisms

The following is a list of the most common bacteria that cause CAUTIs (uropathogens). These bacteria usually originate from either a patient’s gastrointestinal tract or the contaminated hands of health workers.

- Escherichia coli

- Klebsiella spp.

- Proteus spp.

- Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Coagulase-negative staphylococci

- Enterococcus faecalis

- Candida albicans

The chart below illustrates the most frequently isolated organisms in UTIs in Europe.13 It is helpful to see which microorganisms are most common in a region where surveillance data are regularly available.

Yeasts (Candida spp./Candida albicans) deserve a special mention. They are often found in specimens of people with urinary catheters, but usually represent bacterial colonization rather than infection. For example, in patients who have received antibiotics, yeasts grow because antibiotics kill bacteria, which in turn allows the yeast to grow. Yeasts can also be found in specimens from women who have vaginal colonization with Candida (vaginal thrush).13,14 The presence of yeasts usually does not require treatment with antifungal agents; in most cases, catheter removal is the preferred measure. However, note that in some patients Candida spp. can also cause serious infections requiring treatment with antifungal agents; this decision must be taken by doctors after clinical assessment.

-

Knowledge Check (10 min)

-

Appropriate and Inappropriate Catheter Use (5 min)

Although it is ideal to avoid using catheters, it is not always possible to do so. Knowing when it is not appropriate to use catheters will help you to reduce their unnecessary use in your facility. Click or tap each tab to read about when it is inappropriate/appropriate to use urinary catheters.

Inappropriate catheter use

The following are inappropriate indicators for catheter use:15,16

- for urinary incontinence when nurses can turn/provide skin care with available resources, including patients with intact skin, incontinence-associated dermatitis, stage I and II pressure ulcers and closed deep-tissue surgery;

- routine use of Foley catheter in the ICU without an appropriate indication;

- Foley placement to reduce risk of falls by minimizing the need for the patient to get up to urinate;

- for post-void residual urine volume assessment;

- for random or 24-hour urine sample collection for sterile or nonsterile specimens if possible using other collection strategies (e.g., barrier creams, absorbent pads, prompted toileting or non-indwelling catheters);

- by patient or family request when there are no expected difficulties managing urine otherwise in a non-dying patient, including during patient transport;

- for patients prescribed bed rest without a strict immobility requirement (e.g., lower-extremity cellulitis); and

- for preventing UTI in patients with faecal incontinence or diarrhoea, or for management of frequent, painful urination in patients with UTI.

Appropriate catheter indications

The following are appropriate indicators for catheter use:15,16

- acute urinary retention without bladder outlet obstruction (e.g., medication-related urinary retention);

- acute urinary retention with bladder outlet obstruction due to non-infectious, nontraumatic diagnosis (e.g., exacerbation of benign prostatic hyperplasia);

- Note: consider urology consultation for catheter type and/or placement for conditions such as acute prostatitis and urethral trauma.

- chronic urinary retention with bladder outlet obstruction;

- Note: it is unclear whether a Foley catheter is appropriate for chronic urinary retention without bladder outlet obstruction (e.g., neurogenic bladder) when an intermittent straight catheter is feasible and adequate.

- severe pressure ulcers or similarly severe wounds;

- Note: this includes stage III or IV or unstageable pressure ulcers, or skin grafts of other types that cannot be kept clear of urinary incontinence despite wound care; other urinary management strategies (e.g., barrier creams, absorbent pads, prompted toileting and non-indwelling catheters) should be considered.

- urinary incontinence in patients for whom nurses find it difficult to provide skin care despite other urinary management strategies and available resources, such as lift teams and mechanical lift devices—e.g., if turning causes haemodynamic or respiratory instability, strict prolonged immobility (such as in unstable spine or pelvic fractures), strict temporary immobility after a procedure (such as after vascular catheterization) or excess weight (> 300 lbs) from severe oedema or obesity;

- hourly measurement of urine volume required to provide treatment— e.g., for management of haemodynamic instability, hourly titration of fluids, drips (such as vasopressors or inotropes) or life—supportive therapy;

- daily measurement of urine volume that is required to provide treatment and cannot be assessed by other volume and urine collection strategies (e.g., acute renal failure workup, acute intravenous or oral diuretic management, intravenous fluid management in respiratory or heart failure);

- single 24-hour urine sample for diagnostic tests that cannot be obtained by other urine collection strategies (e.g., urinal, bedside commode, bedpan, external catheter or intermittent straight catheter);

- reduction of acute, severe pain with movement when other urine management strategies are difficult (e.g., acute unrepaired fracture);

- Note: consider other urine collection strategies (e.g., urinal, bedside commode, bedpan, external catheter or intermittent straight catheter).

- improvement in comfort when urine collection by catheter addresses patient and family goals in a dying patient;

- management of gross haematuria with blood clots in urine; and

- clinical conditions for which an intermittent straight catheter or external catheter would be appropriate, but placement by an experienced nurse or physician is difficult; or for a patient for whom bladder emptying was inadequate with non-indwelling strategies during this admission.

For the following situations, indicate whether catheter use is appropriate or inappropriate by tapping the left or right side of the slider.

-

Types of Catheters (10 min)

Now that you know when to use a catheter, let us explore the types of catheters. Here are three types of catheter that are used in health care. Tap the arrows on the image gallery to see each type.

-

Can You Spot the Problem? (10 min)

-

Summary (5 min)

This section focused on the overall epidemiology and causes of CAUTI and risks associated with urinary catheter use, as well as indications for appropriate use. First, you saw how hand hygiene plays a key role in CAUTI prevention, particularly moments 2 and 3. In LMICs, CAUTI is one of the most prevalent HAIs, and one of the most preventable. You can describe how microbes can enter a patient’s urinary tract by extraluminal or intraluminal routes. Although you know that CAUTI is caused by microbes entering the body, you can also identify patient, HCW and systemic risks that contribute to the risk of CAUTI in health care facilities. You can now explain appropriate and inappropriate indications for catheter use. You can use what you have learnt in this module to understand and develop a multimodal approach to prevent CAUTI in your health care facility which is part of the next section of this module; here, you will learn more about how to safely insert a catheter, plus key principles and practices of CAUTI prevention.

-

References

- Hand Hygiene poster http://www.who.int/gpsc/5may/hh-urinary-catheter_poster.pdf?ua=1.

- Damani N. Prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. In: Friedman C, Newsom SWB, editors, IFIC basic concepts of infection control, 3rd edition. Craigavon: International Federation of Infection Control; 2016 (http://theific.org/basic-concepts-english-version-2016/).

- Umscheid CA, Mitchell MD, Doshi JA, Agarwal R, Williams K, Brennan PJ. Estimating the proportion of healthcare-associated infections that are reasonably preventable and the related mortality and costs. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32(2):101–14.

- Report on the burden of endemic healthcare-associated infections worldwide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011 (http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/80135).

- Chenoweth CE, Gould CV, Saint S. Diagnosis, management and prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2014;28(1):105–19;

- Lo E, Nicolle LE, Coffin SE, Gould C, Maragakis LL, Meddings J et al. Strategies to prevent catheter-associated urinary tract infections in acute care hospitals: 2014 update. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(5):464–79.

- Maki D, Tambyah P. Engineering out the risk of infection with urinary catheters. Emerg Infect Dis 2001;7(2): 342–7.

- Guide to preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections: implementation guide. Arlington, VA: Association for Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology; 2014 (https://apic.org/Resources/Topic-specific-infection-prevention/Catheter-associated-urinary-tract-infection).

- Chenoweth C, Saint S. Preventing catheter-associated urinary tract infections in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2013;29(1):19–32.

- Mangukiya JD, KD Patel, MM Vegad. Study of incidence and risk factors of urinary tract infection in catheterised patients admitted at tertiary care hospital. Int J Res Med Sci. 2015;3(12):3808–11.

- Dougnon TV, Bankole HS, Johnson RC, Hounmanou G, Toure IM, Houessou C et al. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections at a hospital in Zinvie, Benin. Int J Infect. 2016; 3(2):e34141.

- Manojlovich M, Saint S, Meddings J, Ratz D, Havey R, Bickmann J et al. Indwelling urinary catheter insertion practices in the emergency department: an observational study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(1):117–9.

- Most frequently isolated microorganisms in HAIs [website]. Solna: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control; 2018 (https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/point-prevalency-survey-database/microorganisms-and-antimicrobial-resistance-1).

- National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) [website]. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018 (https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/datastat/index.html).

- Meddings J, Saint S, Fowler KE, Gaies E, Hickner A, Krein SL et al. The Ann Arbor criteria for appropriate urinary catheter use in hospitalized medical patients: results obtained by using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(9 Suppl):S1–S34.

- Guideline for prevention of catheter-associated urinary tract infections (2009). Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009 (https://www.cdc.gov/infectioncontrol/guidelines/cauti/index.html).

- Allegranzi B, Bagheri Nejad S, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011 Jan 15;377(9761):228-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4. Epub 2010 Dec 9.