Implementation Strategies & Quality Improvement

Implementation strategies help you create structured change and translate IPC standards into practice at the point of care in your facility. As the IPC focal person, it is important for you to understand how to develop and maintain IPC interventions. In this module you will learn about the basics of implementation science and how multimodal strategies can support behaviour change and influence stakeholders.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- Describe how the three factors of successful implementation—context, innovation, and recipients—define a framework for improving IPC activities.

- Explain how understanding behaviour change can be used to develop and implement the best IPC interventions.

- Select the best strategies to use when attempting to make low cost or no cost improvements.

- Develop quality improvement (QI) strategies that can be used to systematically improve processes and outcomes.

Learning Activities

-

Not Enough Beds (5 min)

Nikhil is the IPC focal person for a rural hospital. The rural hospital does not see a large population of patients throughout the year and has a small, but adequate staff. This year, however, that is not the case. There has been a significant increase of children sent to the hospital with a diarrhoeal disease. Since the increase began, Nikhil has been uneasy about the ratio of beds to staff, which sometimes results in more than one child in a bed. In the beginning, the situation seemed to be under control. The staff workload had been manageable, and the number of beds available for patients was still higher than the number of cases coming in on a daily basis. However, this did not last long.

Since the increase in children admitted with diarrhoea began a month ago, Nikhil has noticed longer waiting times for beds for patients that arrive in the morning. While the small team of staff has always been able to keep up with large influxes of patients before, this situation is proving to be difficult for them to manage.

Nikhil recently attended a district training on the WHO IPC Core Components. He recognizes that the bed occupancy, staffing, and workload component of his IPC programme should be revisited to adjust for events like this one. He’s hoping to strategically implement an innovation that will help the staff cope with this situation. In the following activities we will apply implementation science to Nikhil’s situation as he develops a solution.

-

What Is Implementation? (5 min)

Implementation is the method that promotes the adoption and integration of research evidence and standards into clinical, organizational, and professional practice to improve the quality of health care and impact patient outcome—that is, quality improvement!1 In other words, implementation means the process of putting a decision or plan into practice. Sometimes these new IPC practices are called “innovations”. Understanding what factors to consider when implementing a change or new practice/innovation is key to translating the Core Components from guidelines to reality.

Quality improvement in IPC usually involves individual, team, and organisational behaviour change. Understanding cultural, behavioural, organisational, and clinical factors that influence behaviour change is essential for successful implementation of guidelines and their associated interventions. Several frameworks have been used to understand how these different factors interact with each other and how best to design your improvement interventions.

A process to create beneficial change and attain desired levels of performance.Think of implementation as the process of building something. In order to build, you must follow instructions. The research evidence tells you what needs to be done, but you must follow a process and use tools and skills to make it happen. Sometimes you may even need to ask for help or make modifications to increase the potential for improvement.

-

Three Factors of Successful Implementation (10 min)

Many things can influence the likelihood of implementation success.

Click or tap on the tabs below to learn more about the three factors of successful implementation.

Context

Context refers to the internal and external situation.

The internal (inner) context refers to the situation in your health care facility. Internal contextual factors influence implementation and can act as either barriers or facilitators. These factors may be related to the culture of the facility, its priorities, or its leadership. Leadership support, which is part of the “Live it” element of the multimodal strategy, can influence the success of implementation. If a local leader does not support the intervention, success will be difficult to achieve. Leadership factors include the culture and the priorities of an organisation.

For example, in Nikhil’s clinic overcrowding and multiple patients sharing beds has become the “norm”. The culture in the clinic is that everyone accepts overcrowding as “business as usual”. Although the clinic leader is aware that this may not be safe, he has too many other priorities to juggle.

External (outer) context refers to things outside of a hospital or clinic or district medical centre that influence implementation. This may include government policies, political incentives or punishments (such as fines), community and civil society lobby groups, and activists.

For example, the WHO Core Components is an international standard developed by an organisation external to Nikhil’s clinic. The national government has mandated that all health facilities, including Nikhil’s must implement the Core Components. In the scenario at the beginning of this module, Nikhil becomes aware of bed occupancy as an IPC concern because of the WHO Core Components. Since WHO is seen as a credible organization and the national government have made their support for these guidelines visible, the guidelines can be viewed as a positive outer context.

Innovation

The innovation is the intervention that is to be implemented to change behaviours. Successful implementation depends on the intrinsic characteristics of the innovation, such as the added benefit it would bring to the users, or the known or available evidence about its impact. An innovation is more likely to be successful if it is easy to use or apply. Innovations should be supported by research results, clinical studies, and evidence from local experience.

Recipients

For implementation to succeed, the recipients of the innovation must buy in to it. Recipients of an innovation can be the health care workers in a facility and even patients and their caregivers. Recipients must believe in it, be motivated to use it, understand it, and be convinced of its benefits. It’s important to know the motivation, beliefs, values, and goals of individuals and teams. Their skills, their knowledge, the time available to them, and the resources to support the intervention are all relevant. Recipients may therefore need support. As an IPC leader it is your job to discover what recipients need to feel supported, and how you can help meet those needs.

As you can see, implementation is influenced by many factors. As you plan to implement any new intervention, innovation, or improvement awareness of these factors enables you to map out where you need to act and what support you might need. Whether you want to improve hand hygiene and waste management, or decrease the risk of infections associated with urinary catheterization, you will need to think about the internal and external context, the appropriateness of the innovation itself, how to support the people on the receiving end, and the likely barriers to success. Remember, each culture, society, and organization will be different and therefore implementation will require close attention to how those factors affect how you approach implementation.

-

Nikhil's Innovations (5 min)

At the training Nikhil attended, he remembered people talking about the problem of bed occupancy. A few attendees had shared some ideas they had to address high bed occupancy and adequate staffing. He’s thankful that he paid attention to this discussion, even though at the time he wasn’t facing that problem.

Because this situation is primarily affecting children, Nikhil has made it a priority to convince the hospital leaders to allocate resources to a specific unit of the hospital just for these patients. He arranges a meeting with the senior leaders and presents the data he has gathered about the increase in diarrhoeal cases and the importance of stopping spread in the facility. He proposes a solution that colleagues from another hospital have suggested: to use smaller beds for pediatrics, which will allow more beds to be installed. He reminds the leaders of the national mandate and asks whether there is extra funding available from the government to procure smaller beds. He also emphasizes that the local community has a lot of trust in the hospital and that community leaders have voiced their concerns to him about the overcrowding – many of them remember a large diarrhoeal outbreak that occurred in the last decade and are anxious not to repeat what happened.

Nikhil also hopes to reduce the amount of time a patient must wait for treatment once they’ve been admitted. He hopes that by discharging patients in the mornings, wait times throughout the day will decrease. This change has been successful in a larger urban hospital where Nikhil previously worked, and he hopes it will work at his facility.

-

Behaviour Change (5 min)

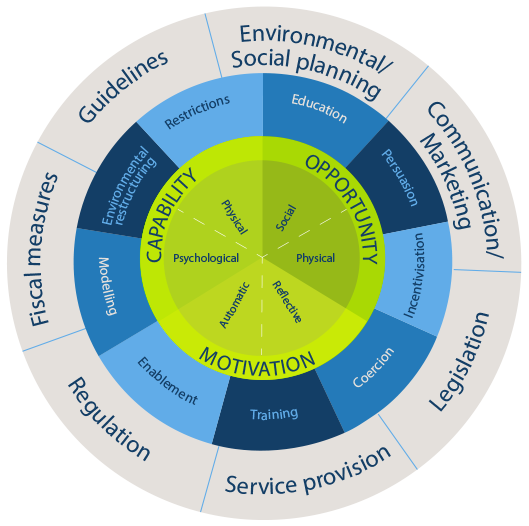

Nikhil may encounter staff who are resistant to the changes he wants to make. Without the commitment and buy-in of everyone at the clinic, it’s unlikely that Nikhil’s innovations will be successful. The Multimodal Strategy can aid Nikhil in overcoming that resistance because it is informed by behaviour change science. The Behaviour Change Wheel, which synthesizes 19 frameworks for behaviour change from various disciplines into one approach, helps to illustrate and describe the theories behind WHO’s Multimodal Strategies and five-step approach to successfully implementing interventions. Understanding the Behaviour Change Wheel will help you build your knowledge of behaviour change theories and empower you to better understand the thinking behind the multimodal strategy. It provides a structured approach to designing or updating behaviour change in interventions and strategies.

Michie Michie S, van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011; Apr 23;6:42Let’s look at the various elements of the Behaviour Change Wheel and see how they relate to the Multimodal Strategy. Click or tap each layer of the wheel to explore the key elements.

The inside layer shows the three sources of behaviour that need to be targeted when implementing an intervention. These are capability, motivation, and opportunity. The success of your interventions depends on addressing each of these according to your local situation. You’ll learn more about these in Step 1 of WHO’s five-step approach to implementing innovations.

The middle layer shows the intervention functions. Which one (or ones) you use depends on what behaviour you want to change. These functions include:

- Education. Informing recipients of the change needed and the implementation plan, and explaining to them the principles supporting the intervention. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to teach it.

- Persuasion. Communicating with posters, campaigns, articles, or other relevant media that may reach recipients. Persuasion can also be enhanced through the use of data which are powerful when fed back to health care workers. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to check it.

- Incentives. Using a rewards system that will motivate recipients. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to live it.

- Coercion. Using a punishment tactic to dissuade recipients from not complying with behaviour change plans – although not recommended within the Core Components, this may be considered appropriate in some cultures. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function would align to live it.

- Training. Enabling recipients to develop skills needed to comply with behaviour change plans. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to teach it.

- Restriction. Setting limits that keep recipients from engaging in the unwanted behaviour. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to live it.

- Environmental restructuring. Changing the physical or social environment to give recipients better opportunity to change. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to build it.

- Modelling. Designating or becoming a champion for your innovation. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to live it.

- Enablement. Trying your best remove barriers that may impede the success of your innovation. In the Multimodal Strategies, this function aligns to build it.

The outer layer represents external factors that help to support implementation. These may be national guidelines, policies, legislation, regulations, etc. Think of this layer as the external contextual factors that will affect whether your innovation is successful.

-

Successful Implementation in IPC Programmes (5 min)

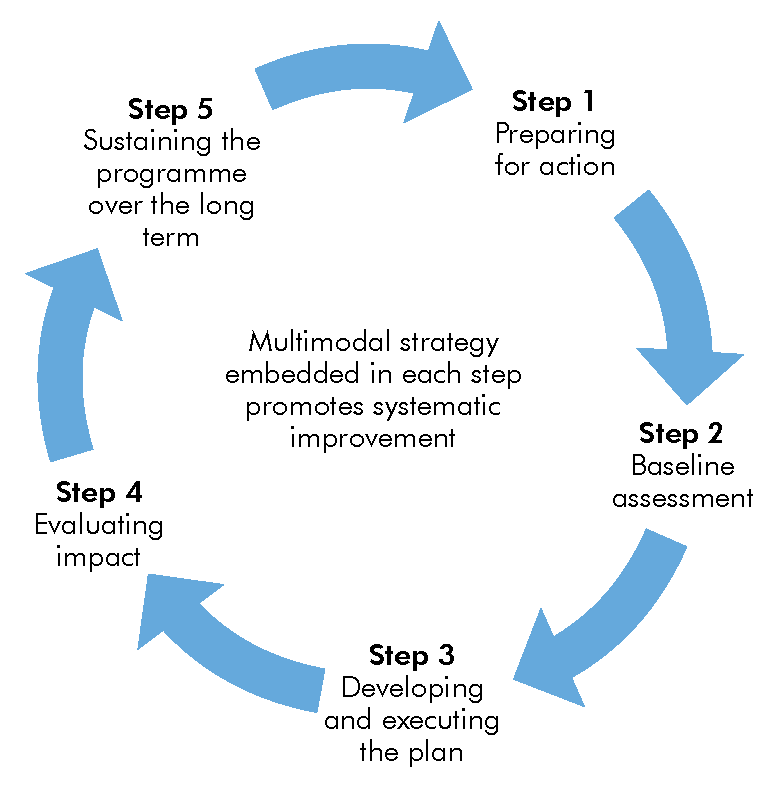

WHO has developed a five-step approach for implementation of IPC interventions based on project management principles. This graphic illustrates that five-step approach, which we’ll cover in more detail in the following activities. The steps to this approach are cyclical, that is, the process continuously promotes systematic improvement. Click or tap each step to learn more.

Step 1. Preparing for action

Ensure that all of the prerequisites for success are in place and addressed. This includes planning and coordinating activities, identifying roles and responsibilities, necessary resources (both human and financial), infrastructures, and identifying key leaders and “champions”, including an overall coordinator and deputy.

Step 2. Conducting a baseline assessment

Conduct an exploratory baseline evaluation of the current situation or practices, including existing strengths and weaknesses.

Step 3. Developing and executing an action plan

Use the results of the baseline assessment to develop and execute an action plan based around a multimodal improvement strategy.

Step 4. Evaluating impact

Conduct a follow-up evaluation to assess the effectiveness of the plan with a focus on its impact (change of system, practices, or knowledge), acceptability, and ideally, cost-effectiveness.

Step 5. Sustaining the programme over the long term

Develop an ongoing action plan and review cycle to support the long-term impact and benefits of the programme. Analyse the extent to which it is embedded across the health care system and country, thus contributing to its overall impact and sustainability.

The next several learning activities will cover these steps in more depth.

-

Step 1. Preparation and Planning (5 min)

From the start, the plan for your IPC intervention or project must be as specific as possible. This means specifying the behaviour you want to change. Identify who needs to do what, where do they need to do it, when do they need to do it, how often, and for how long.

Identify the behaviour: Be clear and specific about the behaviour(s) you would like to change. This allows you to be more focused when it comes to understanding these behaviours. This activity is crucial for the success of your intervention.

Begin by specifying what behaviour needs to start, change, or stop. This step is based on the center of the Behaviour Change Wheel. Define who needs to adopt this new behaviour, when and where this change needs to occur, and how often or for how long the change should happen. There are three sources of behaviour:

Capability: This refers to the psychological or physical ability to perform the behaviour change (i.e., you need to know what to do and how to do it).

For example, ask yourself:

- Do health care workers know the 5 Moments for Hand Hygiene?

- Do they know the correct technique?

Motivation: This refers to whether the people who need to change their behaviour believe in the innovation, whether they value it.

For example, ask yourself:

- Do health care workers believe that hand hygiene is worthwhile?

- Do health care workers value the results of hand hygiene audits?

Opportunity: The physical or social environment in which the innovation will take place must aid in behaviour change. These environmental factors include time, money, resources, location, cultural norms, etc.

For example, ask yourself:

- Is hand rub available at the point of care?

- Is there a system for replenishing empty bottles?

- Do the sinks work?

-

Step 2. Baseline Assessment (10 min)

In Step 2, you should make a baseline assessment (in Step 4 you will use the same type of assessment to measure impact and progress). The assessment can be conducted using tools to assist you in assessing your local situation related to process, practices, infrastructures, and outcomes relevant to your IPC project. WHO has developed a range of IPC assessment tools, including tools to evaluate the level of progress in implementing the Core Components at the national and facility level. The baseline assessment is a critical step in how you will design and execute your intervention. See the resources page for the national and facility practical manuals, the National Infection Prevention and Control Assessment Tool (IPCAT2) and instructions for how to use the tool, and the IPC Assessment Framework (IPCAF).

Let’s return to our scenario with Nikhil. Answer the questions below for the two interventions Nikhil is considering:

- Using smaller beds for pediatrics, which will allow more beds to be installed

- Discharging patients in the mornings

List an internal and an external context consideration for each innovation. Click or tap the compare answer button to see an expert’s answer.

-

Step 3. Develop and Execute the Plan (5 min)

We can use the information gathered in Step 2 and the Multimodal Strategy to create a plan for implementation (Step 3). This step is informed by the middle layer (the intervention functions) of the Behaviour Change Wheel. Click or tap on each multimodal strategy to read how you can use it in your plans.

Build it

Determine what is needed to build the best supportive system for change.

Teach it

Review what you learned about adult learning theories to use the most appropriate teaching approaches.

Check it

Agree on how you will check whether a change has taken place and whether practices have improved.

Sell it

Consider what methods you might use to sell the change and constantly remind workers of the right actions.

Live it

Consider what methods you might use to secure the necessary institutional support and individual and team participation towards a culture that values the change in practice you want to achieve.

To reduce wait times for beds, bed occupancy, and staffing issues, Nikhil has opted to attempt to streamline the admittance and discharge processes. Getting the patients in and out of the hosptial in a timely manner reduces the number of beds used, allows the staff to stay organized, and helps patients feel better faster. Restricting discharge times to the morning is just the beginning of his streamlining approach.

-

Step 4. Evaluate the Impact (5 min)

In step four, you will repeat the baseline assessment using the same tool(s) (e.g. IPCAT2 or IPCAF) to evaluate the overall impact of the intervention as part of a continuous cycle of improvement. Review the results of the assessment and give that feedback to your managers and leaders.

-

Step 5. Sustaining the Programme (5 min)

Step 5 is about sustaining the programme. The experience and lessons learned in implementing your intervention that you received in Step 3 and the results you received in Step 4 will guide you in developing an ongoing action plan. This plan should include a review cycle so that you periodically check whether further improvements are needed. This helps to sustain the improvement over the long term.

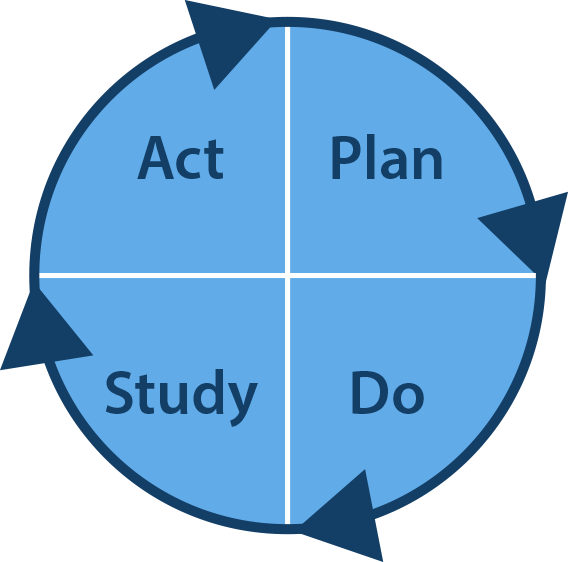

PDSA (Plan, Do, Study, Act) cycles have been used in many countries, often in combination with other QI approaches, and are ideal for small, frequent tests of ideas before making larger, system-wide changes.3s We will focus on PDSA cycles here; however, it is important to note that PDSA cycles are just one example of a QI approach. The Institute for Healthcare Improvement, a worldwide non-profit advocating for health and health care improvement, incorporates PDSA cycles as part of its model for improvement.

In the following graphic, click or tap each word to learn more about the PDSA cycle.

Plan

Use what you have learned about current behaviours and assess what needs changing. Take the necessary steps for preparing your intervention and consider the different factors that can influence that behaviour change.

Do

Use behaviour change models, such as the Behaviour Change Wheel, and project management knowledge to help design the appropriate innovation/intervention.

Study

Evaluate the impact, or success, of the intervention you have just put in practice.

Act

Decide what needs to be further refined or improved. Are there other Core Components that may need to be implemented using the PDSA cycle? Can those improvements benefit other programmes or interventions?

Building a fundamental understanding of QI approaches and learning from applied examples of these approaches will help you to sustain improvements in your IPC programme.

-

No Cost/Low Cost Solutions (5 min)

If you are working in a resource limited setting, you may face multiple challenges when implementing effective IPC interventions. Not all improvement interventions cost a lot of money or require additional resources to complete. Click or tap each tab to learn about three approaches that have the potential to save time and money and improve the quality and safety of health care in limited resource settings.1

Damani N. Journal of Hospital infection 2007; 65(S1): 151-1542No cost

Improve adherence with recommended practices that do not require additional resources.

Examples:

- Remove indwelling devices when no longer needed.

- Use an aseptic technique for all sterile procedures.

- Avoid unncessary vaginal examination of women in labour.

- Place mechanically ventilated patients in a semi-recumbent position.

- Minimise number of people in the operating theatre.

Low cost/ Cost-effective3

Damani N. Simple measures save lives: an approach to infection control in countries with limited resources. J Hosp Infect. 2007;65(Suppl. 2):151-154.Implement cost-effective practices

Examples:

- Provide alcohol-based hand rub and hand washing facilities for hand hygiene.

- Use adequately sterilised items for invasive procedures. This is cost-effective because sterilisation reduces the likelihood of an adverse outcome, which costs more in terms of money and pain for the patient.

- Use single-use disposable sterile needles and syringes.

- Dispose of sharps in appropriate containers.

- Practice adequate decontamination of items/equipment between patients.

- Provide Hepatitis B vaccination to health care workers.

- Manage post exposure for health care workers.

Wasteful practices

Focus on cost-saving measures. The practices in the list below are not evidence-based and wasteful and thus, should not be done.

Examples:

Routine

In rare instances it may be appropriate to do this, but not as a routine practice.- Microbiological swabbing of environment

- Use of disinfectants for environment cleaning (e.g., floors and walls)

- Fumigation of isolation room with formaldehyde

Unnecessary

- Use of overshoes and dust attracting mat

- Use of Personal Protective Equipment in the Intensive Care, & Neonatal Unit when not performing clean procedures or in contact with patients.

Excessive/unnecessary use of

- IM/IV injections when not needed and an oral alternative is available and safe to be used

- Insertion of indwelling devices (e.g., IV lines, urinary catheters, nasogastric tubes) when not indicated

- Antibiotics both for prophylaxis and treatment (including prolong courses)

- Inappropriate antibiotic prescribing

-

Injection Safety (10 min)

How might we apply the three factors that influence success (context, innovation, and recipients) to better understand how to best implement an injection safety improvement?

A year ago, when Joan noticed what seemed to be an increase in needlestick injuries among health care workers in her facility, she was informed that health care workers were repeatedly recapping needles. She decided to do something about it by starting a programme of training and education, targeting all staff members on sharps safety. Joan’s efforts yielded a small change in behaviour. Recapping of needles and needlestick injuries, however, continued to be reported across the facility.

Recently, after talking to a colleague and mentor in a nearby facility, Joan suspected that the main reason that recapping was still occurring was due to her focus on only one improvement strategy—that is training and education. Joan realized that targeting only staff training and education, while necessary, was not sufficient to change behaviour.

Joan and the IPC team hope that using a multimodal approach focused on no-cost/low-cost measures they can improve compliance with sharps safety and reduce needlestick injuries. By collecting data on the extent of the problem and sharing the results with managers Joan can back up her request that the hospital buy smart injection devices/safety engineered devices.

-

Reducing HAI in Rwanda (20 min)

Let’s look at this case study based on an article by Nyiratuza, et al.2

Adeline Nyiratuza Rex Wong Eva Adomako Jean D’Amour Habagusenga Kidest Nadew Florien Hitayezu Fabienne Nirere Emmanuel Murekezi Manassé Nzayirambaho, (2016),A quality improvement project to improve the accuracy in reporting hospital acquired infections in post cesarean section patients in a district hospital in Rwanda, On the Horizon, Vol. 24 Iss 4 pp. 319 - 326.Gihundwe district hospital in Western Province, Rwanda, conducted a quality improvement project to improve reporting of HAI rates for post-caesarean section patients.

Originally, the nurse in charge of the maternity unit was the only person to identify HAIs. No other members of the team were involved in collecting data on HAI, including nurses and midwives. There was no set schedule or routine for the nurse in charge to identify HAI, and HAI could be missed when she was not on duty.

Two criteria were used to identify HAI:

- Pus found in the surgical wound

- Suspected urinary tract infection

If the nurse in charge discovered an HAI case, she would document it in a registration book, but didn’t include any patient details or the type of HAI. The HAI rate was calculated monthly based on the data from the registration book.

According to routine reports from the maternity unit, the average HAI rate in 2014 was 1.64%, which is significantly lower than rates reported by other Sub-Saharan African countries (their average was 7.3%) and by high income countries (average 4.8%). Hospital leadership suspected under-reporting and had no confidence in the data.

To improve the reporting of HAI rates, an intervention was developed and implemented consisting of four main components.

- The implementing team revised the criteria used to identify HAI in the maternity unit. Remember, before the intervention, the maternity unit only used two criteria to determine HAI: pus and urinary tract infection. With only two criteria, it is likely that some cases were missed, resulting in under-reporting.

For the intervention, clinical staff were asked to use the WHO clinical signs and symptoms tool to identify HAI. An HAI data collection form was created to allow the maternity unit staff to record each case. - The second component of the strategy involved distributing the HAI reporting responsibilities more equally among all maternity unit staff. Recall that prior to the intervention, reporting HAI relied solely on one person: the nurse in charge of maternity. HAI may not have been recorded when she was absent.

For the intervention, each day a new person was responsible for checking patients and documenting in the data collection form when HAIs were detected. The nurse in charge of the maternity unit created monthly summary reports based on the data collected. The summary reports were then submitted to the IPC committee and chief of nursing for analysis and recommendations. - They improved record keeping for auditing purposes. Before intervention, suspected HAIs were recorded in the registration book only. In the new process, a dedicated folder was created to file all completed HAI forms.

- A guideline on the use of the new HAI surveillance form and new process was created and publicised across the hospital. All midwives and nurses in the maternity unit received trainings on the new guideline in January 2016.

To measure the accuracy of the routine HAI surveillance report, a validation team was created to collect HAI data for all patients who underwent caesarean sections in the maternity unit. The team used a surveillance form that was adopted from a WHO tool which uses clinical signs and symptoms to identify HAI.

The HAI data collected by the validation team were compared against the HAI rates found in the routine unit reports during the same period. When discrepancies were found, the validation team would audit the patient’s file to confirm the final HAI result, then verify that proper follow-up had been given to the patient, and ensure documentation was completed. The primary outcome was the difference between the HAI rates detected through routine unit reports and the HAI rates detected though the validation team’s processes. This discrepancy of HAI was measured in the pre and post intervention for comparison.

The QI team for this project was met with some challenges in the early phases of implementing these innovations. First, there was some resistance by staff. The new reporting process meant extra work for nurses and midwives, some of whom would forget to record the HAI data. The team overcame this resistance by communicating more frequently with the staff about the importance of these innovations.

Second, there was difficulty coordinating staff schedules. The nurse-in-charge had to continuously and rigorously follow-up with the staff to keep them engaged and informed of progress.

Third, one training for all nurses and midwives on the new guidelines wasn’t sufficient for them to change their behaviour. Repeated trainings and one-on-one sessions were needed.

Finally, there was a language barrier. The guidelines needed to be translated, which delayed implementation of the innovations.

-

Summary (5 min)

In this module we learned that context, innovation, and recipients are the three factors of successful implementation that define a framework for improving IPC activities. We also learned about the components of behaviour to be targeted: capability, motivation, and opportunity. Identifying the specific behaviour that we would like to change helps us to understand why that behaviour occurs. The Behaviour Change Wheel is a tool that can be used to identify functions that will support our interventions. Finally we saw how the multimodal strategy incorporates behaviour change theories and provides a practical structure to support implementation.

In resource-limited settings, it is important to consider and select low cost or no cost strategies when implementing our interventions. There are many creative ways to approach these solutions; this module included a non-exhaustive list.

Last, we learned about QI strategies (such as the PDSA cycle) that we can use to systematically improve and sustain processes and outcomes. They must be implemented cyclically to guarantee improvement.

-

References

- 1Ferlie E, Fitzgerald L, Wood M. Getting evidence into clinical practice: an organisational behaviour perspective. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2000;5(2):96–102.

- 2Damani N. Journal of Hospital infection 2007; 65(S1): 151-154

- 3Edwards R, Sevdalis N, Vincent C, Holmes A et al (2012) Communication strategies in acute health care: evaluation within the context of infection prevention and control, J Hosp Inf;82: 25-29