Microbiology

Microbes are living organisms that can be beneficial, neutral or harmful to humans. In this module you will learn about how disease-causing microbes, called pathogens, are classified, identified and transmitted. You will be introduced to basic microbiological principles, fundamental laboratory diagnostics and mechanisms by which microbes transmit and cause diseases. This information helps health care professionals understand the situation at hand and determine the most effective treatment options. A basic understanding of microbiology will allow you to recognize how your role as an IPC person can help break the cycle of transmission, prevent health care-associated infections (HAI) and reduce antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- define microbes and other microbiology terms;

- describe the chain of infection;

- describe main groups of microorganisms;

- discuss common multidrug-resistant organisms; and

- describe basic laboratory diagnostics.

Learning Activities Estimated time:

-

What Are Microbes? (5 min)

Microbes are everywhere. They are living organisms that have existed on this planet for over 3 billion years, and are essential for humans to live and function. Pathogens are microbes that cause disease—but not all microbes are pathogens. Many microbes are normal human flora. Inside the human body, there are 10 trillion human cells and 100 trillion bacteria, protozoa, and fungal cells. When these microbes appear in parts of the body where they do not belong, they can cause infection.

Microbes are categorized according to their biological classification (also called biological taxonomy). Organisms are classified into seven main categories: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus and species. Many microorganisms are known by their family, genus and species. For example, bacteria are named by their genus and species, such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Some families of bacteria are known pathogens in health care, such as the Enterobacteriaceae family.

Microbes can be divided into five categories. Click or tap the tabs below to learn more about microbe classifications, how they are identified in a lab, and how they are treated:

Bacteria

- Characteristics:

- unicellular (single cell), no nucleus

- largely harmless (normal flora)

- different growth characteristics with and without oxygen

- named by genus and species, such as Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus auerus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

- How to identify:

- visible with ordinary light and magnification (microscope)

- Gram staining, culture, other specialized laboratory tests

- Examples of pathogens:

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA)

- Neisseria meningitidis

- opportunistic pathogens—usually do not cause disease but take advantage of abnormal circumstances, such as a weakened immune system and cause disease

- Treatment:

- antibiotics

Hover or tap to zoom

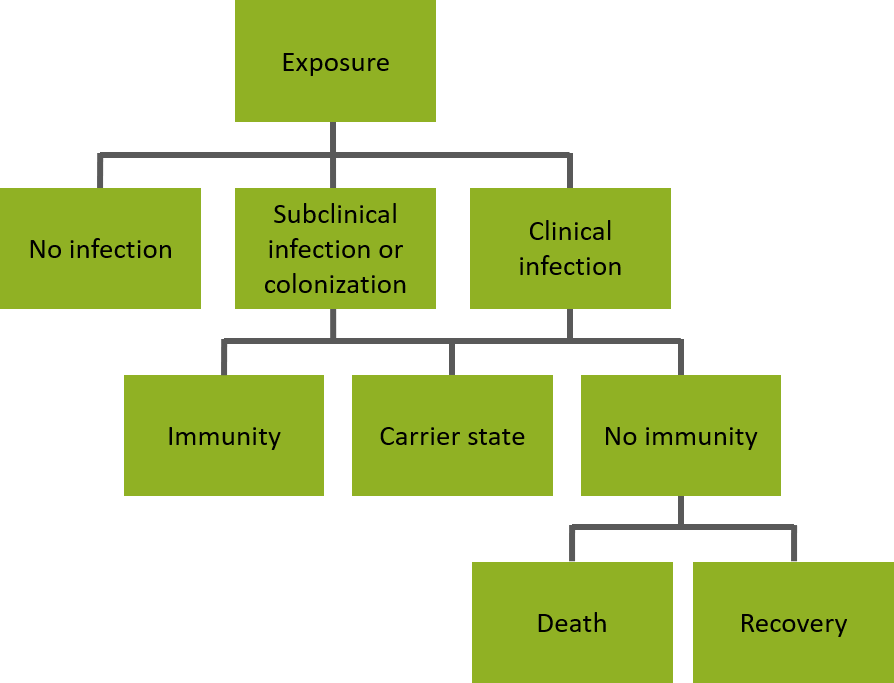

Produced by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), this digitally-colorized scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image depicts numerous mustard- colored, spheroid-shaped, methicillin-resistant, Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) bacteria, enmeshed within the pseudopodia of a red-colored human white blood cell (WBC), known more specifically as a neutrophil.

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library.Viruses

- Characteristics:

- acellular

- only able to replicate in a host’s cells

- 10,000 times smaller than bacteria

- viruses have single names (ebola, influenza, measles).

- How to identify:

- grown in cell lines; identified using specific fluorescent stains or methods such as enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

- Examples of pathogens:

- influenza virus

- measles virus

- Ebola virus

- Treatment:

- antivirals or supportive treatment

Hover or tap to zoom

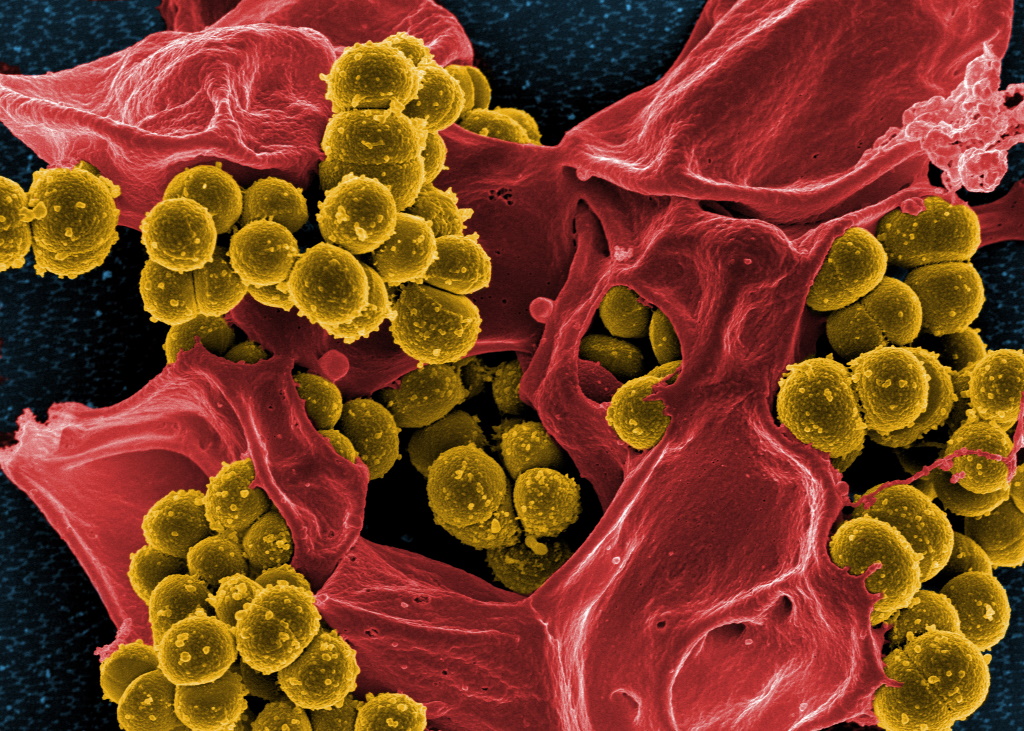

Produced by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), under a magnification of 25,000X, this digitally-colorized scanning electron microscopic (SEM) image depicts numerous filamentous Ebola virus particles (red) budding from a chronically-infected VERO E6 cell (blue).

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library.Fungi

- Characteristics:

- unicellular and multicellular

- most fungi are not dangerous (yeast, mould, mushrooms), but some can be harmful to health

- How to identify:

- culture and special stains

- Example of pathogens:

- Candida albicans

- Treatment:

- antifungals

Hover or tap to zoom

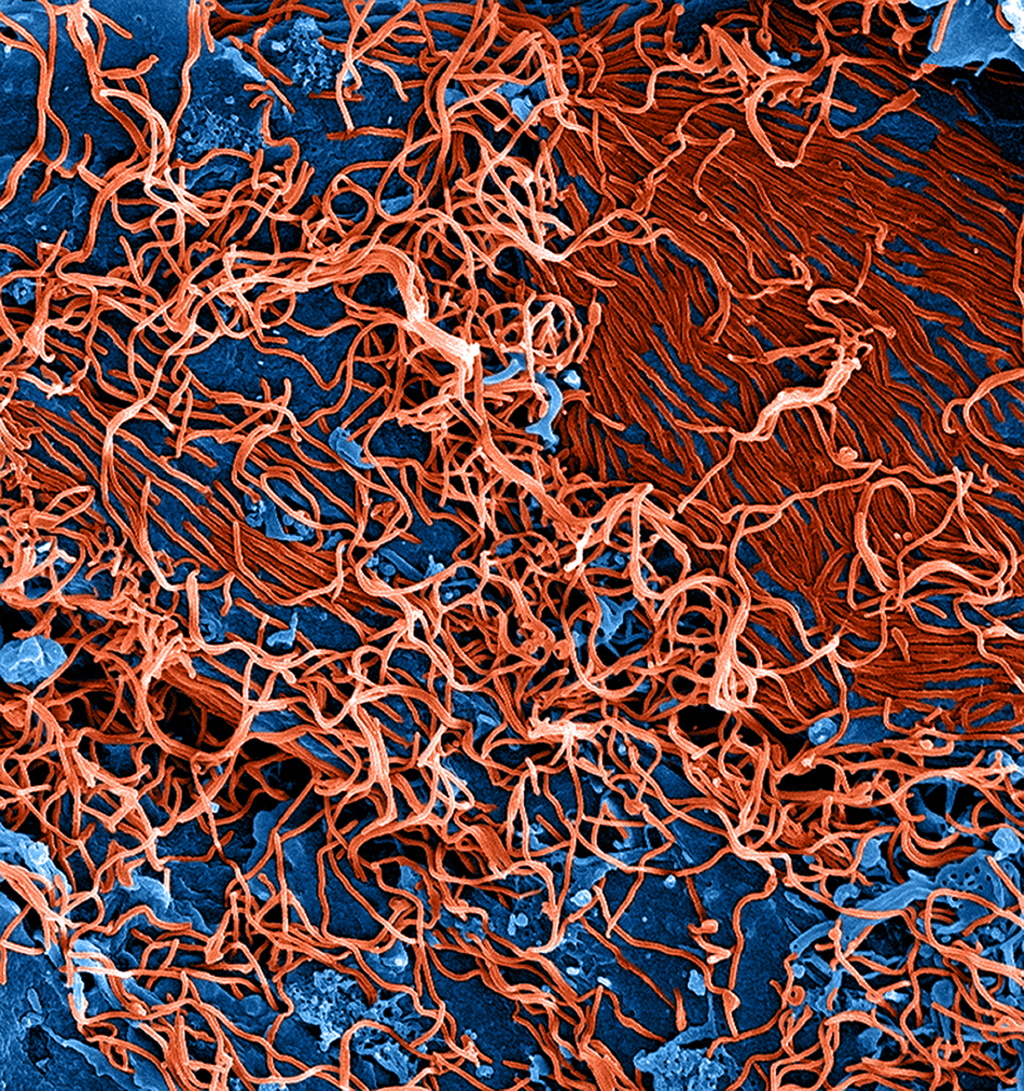

Under a magnification of 475X, this lactophenol cotton blue-stained specimen revealed some of the ultrastructural morphology exhibited by a Fusarium sp. fungal organism. Of importance here, are the septate filamentous hyphae, and the floral arrangement of the fusiform-shaped macroconidia. See PHIL 17972, for a higher magnification of this image.

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library.Parasites

- Characteristics:

- organisms that live on or in a host organism and gets their food at the expense of the host

- unicellular or multicellular

- How to identify:

- microscopes, blood tests

- Example of pathogens:

- malaria (Plasmodium)

- guinea-worm disease (Dracunculus medinensis)

- Cryptosporidiosis diarrheal disease (Cryptosporidium)

- Treatment:

- antiparasitics

Hover or tap to zoom

This low-power photomicrograph reveals some of the ultrastructural morphology exhibited by coupled male and female Schistosoma mansoni parasites. “Unlike the flukes, adult schistosomes are either male or female, with the female residing in a gynecophoral canal within the male. Male worms are robust, tuberculate, and measure 6 mm – 12 mm in length. Females are longer (7 mm – 17 mm in length) and slender. Adult S. mansoni reside in the venous plexuses of the colon and lower ileum and in the portal system of the liver of their host.”

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library.Prions

- Characteristics:

- defective proteins that misfold

- some evidence of transmission due to failure to remove prions from reusable devices.

- How to identify:

- brain biopsy or autopsy (tissue sample under microscope)

- Example of pathogens:

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease (CJD)

- Treatment:

- supportive therapy only; no treatment has been identified

Hover or tap to zoom

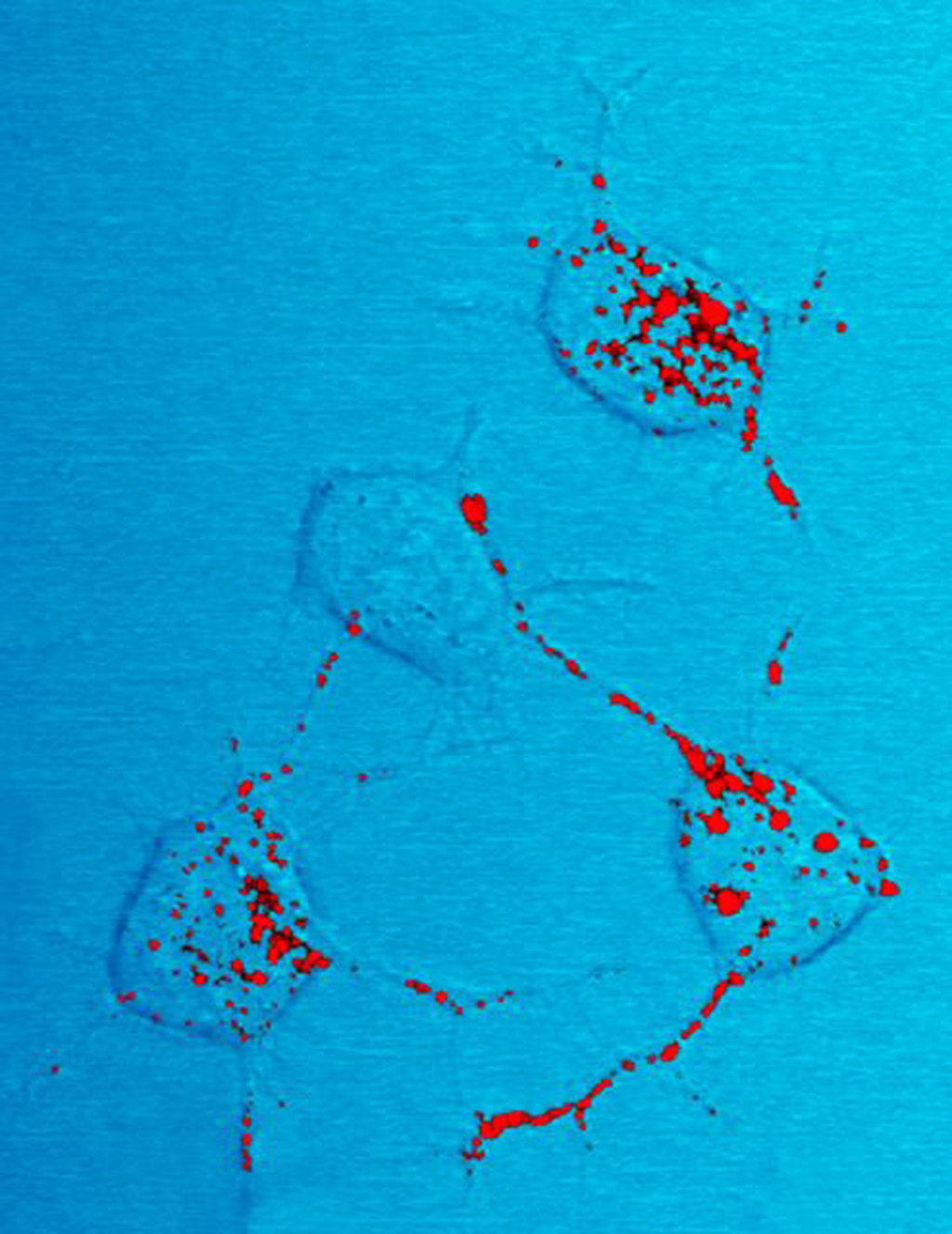

Produced by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), this photomicrograph of a neural tissue specimen harvested from a scrapie-affected mouse, revealed the presence of prion protein stained in red, which was in the process of being trafficked between neurons by way of their interneuronal connections, known as neurites.

Source: CDC Public Health Image Library. - Characteristics:

-

How Do Bacteria Cause Infection? (5 min)

As we have just learnt, most bacteria are important parts of the normal human flora. They help us do such things as digest our food. However, when these bacteria appear in parts of the body where they do not belong, they can cause infection. For example, bacteria normally found in the gastrointestinal tract could cause a urinary tract infection (UTI) if they are introduced to the bladder or kidneys. Closed areas, such as bladders, joints, and the bloodstream, are sterile areas of the body. That means these parts of the body are meant to be free from bacteria or any other living microorganism. When microbes enter these parts of the body, disease and infection can occur.

What is an infection?

The skin, mucous membranes, gastric juices, and blood are part of the body’s defence system. These parts of the body protect against disease-causing pathogens. An infection occurs when a disease-causing organism (a pathogen) enters a host and multiplies.

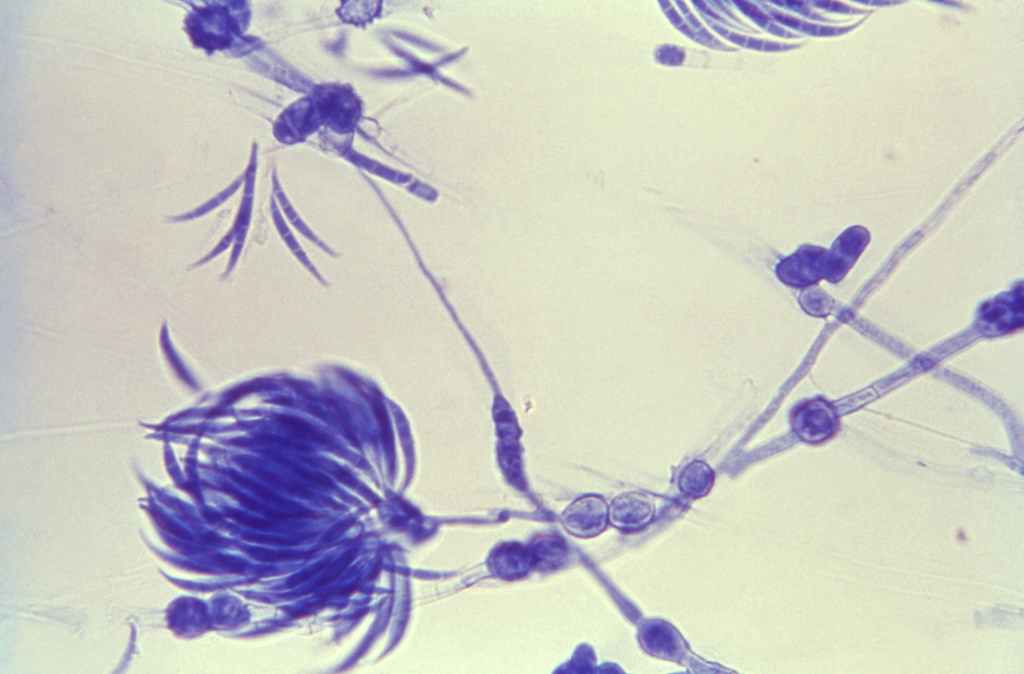

There are different outcomes for a patient after exposure to a disease-causing pathogen. These are described in the diagram below:

Exposure

Many different types of exposure can occur. Exposure can occur in the community or in a health care setting—for example, being pricked by a used needle.

Infection

Even after exposure, there are many factors that determine whether the pathogen will cause an infection.

- It is possible that no infection will occur, even after exposure.

- A pathogen can be present in a host without causing signs or symptoms of disease. This is called a subclinical infection or colonization.

- If a pathogen enters a host and causes signs and symptoms of disease, this is a clinical infection.

Outcomes

For subclinical infections, there are a number of outcomes. If the pathogen has colonized, this means it is present in the body but does not cause disease (carrier state). The immune system can mount a response, which in some cases leads to production of antibodies against the pathogen (immunity). However, even if the immune system mounts a response and creates antibodies, reinfection is possible.

-

How Is an Infection Diagnosed? (5 min)

Signs and symptoms

When the body detects an infection, the immune system reacts to fight it. Signs and symptoms of an infection depend on the pathogen. The following list of symptoms are signs that the body is fighting an infection:

- fever

- pain

- redness

- swelling

- fluid drainage

Laboratory diagnosis

Laboratory testing is not strictly required to diagnose an infection—but identifying the specific pathogen can help guide antibiotic treatment and inform what, if any, IPC interventions may be required to help reduce or prevent the spread of infection to other susceptible hosts. In those facilities without lab access, clinicians should refer to their national treatment guidelines to determine how to choose a suitable antimicrobial treatment.

In clinical labs, the microbiology section identifies and characterizes microorganisms. The first step in identifying bacteria is the Gram stain.

What is a Gram stain test?

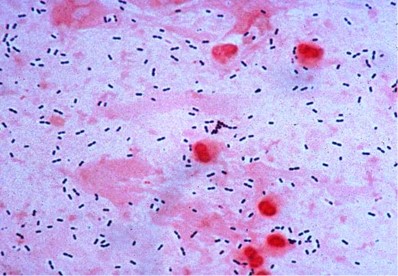

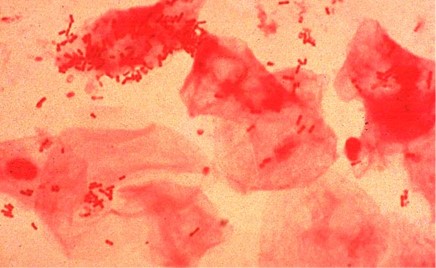

In a Gram stain test, a sample is placed on a slide and dyed with chemicals. Depending on how the bacteria reacts to the stain, the test can determine whether the bacteria is Gram-positive or Gram-negative. Use the image gallery below to learn more about these tests.

A Gram-positive result indicates that the bacteria has a very thick outer layer (cell wall) with additional proteins (peptidoglycan). Gram-positive cells appear purple under the microscope. Examples of Gram-positive bacteria are Staphylococcus, Enterococcus and Streptococcus.

A Gram-negative stain means that the bacteria does not have an extra layer in the cell wall. Gram-negative cells appear pink under the microscope. Examples of Gram-negative bacteria are E coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa and the Acinetobacter species.

The Gram stain takes less than an hour to perform. The result of this test can help clinicians quickly decide which antibiotic to choose.

What is a culture?

Microorganisms that have been grown in a Petri dish using a special growth media are referred to as a culture. The time it takes a culture to grow depends on how long it takes the microorganisms to grow. Some microorganisms grow within hours; others take days to grow. Microorganisms look different from each other when cultured. A trained laboratory technician can identify a bacteria genus, and sometimes species, based on what the culture looks like. Some laboratory equipment is advanced enough to automate the process of culturing bacteria.

How can testing determine AMR?

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST) consists of both manual and automatic tests that use colonies from cultures to determine whether a microbe is susceptible or resistant to drugs. These complex procedures take 2—3 days to be processed by trained microbiologists.

-

How Is a Bacterial Infection Treated? (5 min)

Antibiotics

There are many different kinds of antibiotics. Some antibiotics are capable of killing many kinds of bacteria. These antibiotics are classified as broad-spectrum. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are a good choice when the agent of infection is unknown, because there is a high likelihood that the antibiotic will be effective. However, because they are so good at killing, broad-spectrum antibiotics also kill the normal flora that are beneficial to us. In addition, they are more likely to lead to selection of resistant organisms. Some examples of broad-spectrum antibiotics are chloramphenicol, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, cotrimoxazole, amoxicillin/clavulanate imipenem.

Other antibiotics act only against limited types of bacteria. These antibiotics are classified as narrow-spectrum. Vancomycin, penicillin, and linezolid are examples of antibiotics that will kill Gram-positive bacteria, but not Gram-negative bacteria. On the other hand, aztreonam and colistin will kill Gram-negative bacteria, but not Gram-positive bacteria. Narrow-spectrum antibiotics protect our normal flora and are less likely than broad-spectrum antibiotics to lead to AMR.

What is AMR?

AMR occurs when a microorganism develops protection against an antimicrobial drug. Microorganisms replicate very quickly. E. coli, for example, can double in quantity in about 40 minutes. During replication of genetic material, microorganisms can insert and delete certain portions of their genetic material. They can also pick up extra genetic material that helps them protect themselves against drugs meant to kill them. Due to the rapid way in which microorganisms replicate, AMR can develop quickly.

Resistant microorganisms can place more of a burden on the health care system. These highly resistant organisms increase the risk of morbidity, mortality and disability in patients. They can increase a patient’s length of stay or cause complications that may require admission to ICU. They can also increase the financial burden on patients, who then have to purchase more expensive antibiotics to treat multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs—see below).

Watch the animation to see how antibiotic resistance occurs.

What are MDROs?

When microorganisms become resistant to more than one drug, they are called multidrug-resistant organisms, or MDROs. Laboratory tests are needed to determine if a microorganism is resistant to the drug designed to treat it. In the health care and public health fields, AMR is concerning because it means the microorganism is evolving. For clinicians, this could mean few or no treatment options.

Some MDROs are caused by the overuse and misuse of antibiotics; this includes administering antibiotics when they are not needed, or recommending that they be taken for longer than necessary.

It is increasingly important to identify and sustain systems and strategies that manage the risk of MDROs in your facility. When MDROs are discovered by laboratory tests, the physician and the IPC team should be alerted. Examples of MDROs commonly found in the health care setting include multidrug-resistant Klebsiella spp. and Acinetobacter spp.

-

How Do Infections Spread? (5 min)

How does a disease spread?

Recall the chain of infection diagram (below) from the Introduction to IPC module. Disease transmission occurs when an infectious agent leaves its reservoir or host through a portal of exit. The agent is conveyed by some mode of transmission, either directly or indirectly. When the pathogen enters through an appropriate portal of entry, a susceptible host is infected.

The image below illustrates this cycle.

Scenario

Here is a hypothetical scenario of how diseases can spread in a health care facility:

Marjorie is a health care professional working in the paediatric ward at her facility. A child has been checked in for four days with severe dehydration and diarrhoea. The child has recently been diagnosed with an infection that has been acquired since their admittance to the facility. Marjorie is worried that the infection will complicate treatment for the child, and that the other children in the ward could be in danger of acquiring the same infection.

-

IPC and Microbiology (5 min)

The IPC team is the health facility’s line of defense against the spread of HAI and AMR. Having a basic understanding of microbiology will allow you to make better decisions regarding which interventions to implement in your facility.

Here are some considerations you may need to make as an IPC person:

- Does my facility have, or have access to, a laboratory?

- What is the quality and capacity of the laboratory, if available?

- Are the standardized definitions and methods consistent?

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Summary (5 min)

In this module you have learnt that, although not all microorganisms are harmful, pathogens can spread throughout the health care environment. Through the chain of infection, we can see how a pathogen can cause infection, from the reservoir to the portal of entry in the body. Microorganisms can become drug resistant through the misuse and incorrect administration of antibiotics, which lead to the spread of AMR. Pathogens can become resistant to many drugs; these pathogens are called MDROs. Microbiologists use Gram stains, cultures and many other methods in laboratories to identify and characterize pathogens, which then helps clinicians make appropriate treatment decisions.