Outbreak Investigations: Describing the Outbreak

When an outbreak is identified, you should immediately begin an investigation. In this module you will learn how an outbreak investigation helps determine the cause of the outbreak and stop the spread of the infection. When describing an outbreak, you will learn who needs to be informed of the outbreak, how to define a case definition, identify cases, and describe its epidemiology. You will learn more about analysing an outbreak in the next module.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- explain how an outbreak investigation stops the spread of an outbreak

- identify the steps of describing an outbreak investigation, including:

- identify outbreak investigation team members

- define a o prepare data collection methods to identify new casescase definition suitable to describe the outbreak

- prepare data collection methods to identify new cases

- interpret data collected to describe the epidemiology of the outbreak.

Learning Activities Estimated time:

-

What Is an Outbreak Investigation? (5 min)

The most important reason for conducting an investigation is to stop the outbreak as quickly as possible. Each step of an investigation is activated in order to determine the cause of the outbreak, minimize morbidity and mortality, and improve existing infection prevention and control (IPC) strategies. Investigation procedures can also help prevent litigation and protect the reputation of an institution, improve patient care practices and potentially prevent future outbreaks.

Outbreak investigations can be divided into two parts: describing and analysing.

When describing an outbreak, you will take steps to gather information and describe the outbreak in order to understand and communicate the details of what happened.

- Recognize and establish the existence of an outbreak

- Verify the diagnosis

- Develop a case definition

- Identify and search for cases

- Perform descriptive epidemiology (i.e. analyze and describe data by person, time and place)

When analysing an outbreak, you will make deductions from the data and evidence you gathered earlier to explain what caused the outbreak and determine the risk factors. We will explore this in part 3 of the Outbreak Investigation module.

- Develop hypotheses

- Evaluate hypotheses

- Refine and re-evaluate the hypothesis (if necessary)

- Implement control and prevention measures

- Communicate findings

In real world applications, investigations do not occur sequentially. Many steps often happen at the same time, certain steps may occur several times and, in some cases, some steps may not happen at all.

In this module you will learn the overall steps of an outbreak investigation. As we work through each step, we will note when steps may occur out of sequence.

-

Obi's Guide to Outbreak Investigation (10 min)

Watch this video to get an overview of the steps involved in conducting an outbreak investigation.

-

Outbreak in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (5 min)

To help understand how to apply these steps for outbreak investigation, we will refer to the following case study as an example.1

Each year, the University Hospital in Karachi, Pakistan, delivers over 3000 babies with 600 of those admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). There are three incubators and two cots in the NICU with capacity for admitting five neonates total. The small unit is open concept with one entrance, which is used by both health care workers (HCWs) and mothers. Because of limited beds and more babies requiring NICU admission, the number of neonates admitted often exceeds the maximum allowed, resulting in overcrowding and an increased patient to nurse ratio. Neonates are fed as required. Bottles and the weighing machine are disinfected during every shift. Diapers are changed as required.

A methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) outbreak began in early November in the. Within that month, MRSA was found in the urine samples of five neonates. When the urine culture of the second neonate was confirmed with MRSA, steps to implement control measures were taken, such as ensuring transmission-based precautions and isolation were in place for colonized or infected neonates. Strict adherence to hand hygiene (alcohol-based hand rub or soap and water), and measures for traffic control in the nursery, the operation theatre and labour room were put in place by locking doors so that no one could enter without permission. Protocols for terminal cleaning of all patient care areas were re-emphasized.

You will learn more about this case as we go along. You will see how these steps apply to real world events and how they can be nonsequential.

-

Step 1: Recognize and Establish That an Outbreak Exists (5 min)

In order to recognize an outbreak and act efficiently, a system of detection must be in place. Nursing staff, doctors, IPC professionals, laboratory staff and even the community will act as sources for this system. Early notification is key when an outbreak occurs. An outbreak is suspected when more cases with similar symptoms occur in the unit or the hospital than is expected in a specified time period. It is important to rule out a pseudo outbreak, which can be the result of a change in protocols, staffing or policies. If you suspect an outbreak has occurred, you need to gather more information.

Notify and Inform All Relevant Authorities

Once you have identified the situation as a true outbreak, the next step of an investigation is to notify all relevant authorities as soon as possible. Often this step is done concurrently with step 9: implement IPC measures. Because an outbreak is easier to stop the sooner it is caught, it is important to put these measures into place as soon as possible. Investigation is critical, but IPC measures need to be addressed even before initiating the official investigation.

The Outbreak Management Team (OMT)

Once you have identified and notified the proper authorities, it is time to get the team together. First, identify the team lead. This person will make sure that the steps are being followed, team members are properly informed and action steps are being carried through. Then, share tasks between members. Consider the roles that are best suited for each member of the team. For example, the head of the affected unit would oversee reporting significant data from that unit.

The following is a list of personnel that should be included in the management of an outbreak:

- infection control team or focal persons

- infection control doctor or nurse

- infection control focal point

- additional personnel

- clinical director or designate

- head of the affected unit

- chief nursing officer

- information/media relations unit

- microbiology consultant/microbiologist/laboratory representative

- hospital epidemiologist.

These are the tasks that the OMT will need to carry out:

- follow up cases and actively seek new ones;

- identify exposed patients;

- determine and institute IPC strategies;

- determine why the outbreak occurred (though, as mentioned previously, this is not always possible);

- institute improvements (e.g., new approaches to particular care practices, new cleaning protocols) to prevent further outbreaks; and

- manage information and communication strategies.

Additional measures can be introduced throughout the investigation as more knowledge is gathered. Ensure and reinforce standard precautions and, if necessary, transmission-based precautions. Always weigh the harm/benefit potential of drastic measures such as ward closures to patients and communities.

Case Study: The OMT for the Neonatal Unit

- infection control team or focal persons

-

Step 2: Verify the Diagnosis (5 min)

Verify the Diagnosis

The second step of an outbreak investigation is to verify that the diagnosis is correct. The OMT must be clear on clinical criteria and review any confirmatory laboratory tests (if available) or combinations of symptoms (subjective complaints), signs (objective physical findings) and other findings. The team needs to establish criteria to differentiate between a suspected, probable and confirmed case . Degrees of certainty can be defined as:

- Suspected: Presents with some clinical signs and symptoms of concern.

- Probable: A case that meets the clinical case definition, has noncontributory or no serologic or virologic testing, and is not epidemiologically linked to a confirmed case.

- Confirmed: A case that is laboratory confirmed or that meets the clinical case definition and is epidemiologically linked to a confirmed case. (A laboratory-confirmed case does not need to meet the clinical case definition.)2

Case Study: Microbiology at the NICU

In early November, the first neonate was transferred to the NICU due to transient tachypnoea and grunting. A blood culture was sent to the microbiology lab and the culture grew MRSA. The next day, a second neonate was brought to the unit because of jaundice. The urine culture for both babies came back positive for MRSA.

A third neonate’s urine culture was reported for positive growth of MRSA. Within four days, the fourth and fifth neonate cultures were found to be positive. By now, the IPC committee members had visited the nursery, labour room and operating theatre. The rest of the neonates admitted to the nursery, as well as the entire nursery staff, were screened for MRSA.

-

Step 3: Case Definitions (5 min)

In our MRSA case study, a diagnosis of MRSA has now been verified. The next step is to determine a case definition for the outbreak.

A case definition is a standard set of criteria established in order to determine whether an individual should be classified as having the condition of interest. In collaboration with the OMT, the IPC focal person will develop the case definition. A case definition is initially designed to be more sensitive than specific. This means it is designed to ensure that no cases are missed and to avoid false positives (cases misidentified as part of the outbreak). A dynamic definition may be refined as new information is obtained, meaning it is likely to start out broad and then be redefined more narrowly as the investigation goes on.

Sensitivity is the ability to correctly include infections that are present (that is, the number of HAIs that are correctly diagnosed).Specificity is the ability to correctly exclude infections that are not present (that is, the number of patients who do not have HAIs).A good case definition should include:

- Who: Person or affected population, e.g., age, sex, race, occupation. In this example, the persons affected are neonates admitted to the NICU.

- Where: Place, e.g., geographic location or facility. In this example, the location is the NICU of the University Hospital of Karachi, Pakistan.

- When: Time, e.g., the time period associated with illness onset. In this example, the cases appeared during the month of November.

- What: Combination of simple and objective clinical features (e.g., sudden onset of fever and cough) AND the presence of specific laboratory findings (if applicable). In this example, MRSA was detected in the neonates’ urine samples.

- Degree of certainty: Suspect (general), probable (clinical case definition) or confirmed (laboratory-confirmed). In this example, MRSA was confirmed in lab culture results.

-

Step 4: Search for Additional Cases (5 min)

In our MRSA example, we have now identified the case definition: A neonate that is admitted to the NICU and tests positive for MRSA from any culture site. This case definition will help with the next step of the investigation, identifying additional cases. Creating a data collection form based on the case definition will help track new cases. As you develop the form, keep in mind that it needs to be standardized and easy to use. The data collection form should include:

- patient identifiers (i.e., medical record number or unique identifier)

- demographic information

- clinical information, including symptom onset dates

- risk factors

- laboratory results.

Once the type of data needed has been determined and agreed upon, sources for those data need to be explored. There are numerous ways in which the OMT can collect data. You may start by asking clinical and laboratory staff to notify the team of any new infections or cases. You might interview clinical staff, and, if appropriate, interview patients and their families as well. Review patient records. These may be electronic, case notes, nurses’ notes or any other medical or surgical records. Review any laboratory data associated with these cases. Consider sending out letters to other clinics, describing the outbreak and requesting reports.

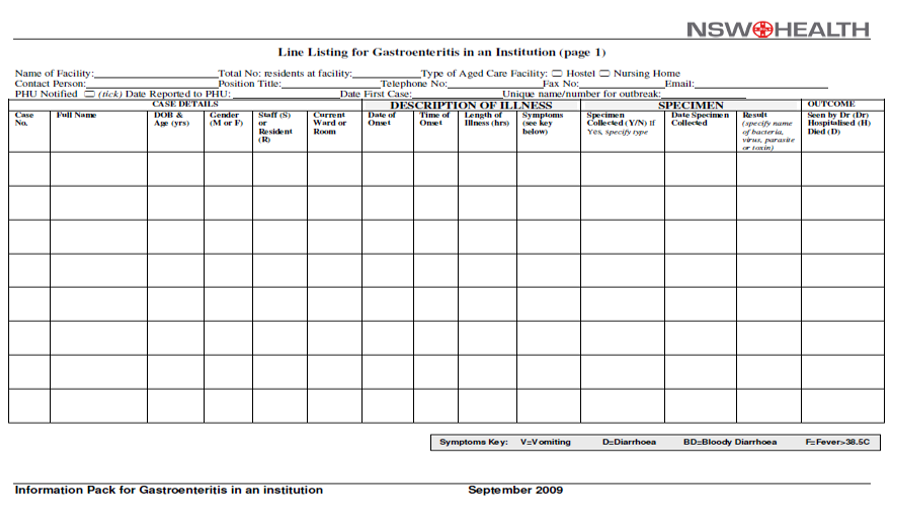

Any new data you receive should be summarized in a line list. A line list helps to characterize the data quickly and describe the outbreak. It is often determined by the situation. However, the line list should have :

- patient name

- unique identifier

- date of birth

- ward/unit

- symptom duration—date of onset to end of symptoms

- risk factors.

This is an example of a line list for gastroenteritis outbreak:

Hover or tap to zoom

-

Step 5: Descriptive Epidemiology (5 min)

In step five, you will use the data that has been collected to describe the outbreak. Descriptive epidemiology is a process that can identify patterns among cases and in populations by person, time and place. We can summarize these data using a line list. The line list allows the OMT to identify the population at risk, determine the timeline and mode of transmission, and search for clues about the source. In this learning activity, you will learn how to

- calculate the timeline and mode of transmission by counting cases over time

- how to create an epidemic curve.

Using Epidemic Curves

The line list can be used to describe the data by person, which allows investigators to know the characteristics of the affected cases and identify those who may be at risk. A frequency table is a method of organizing raw data into a form that is easy to display. From a line list, you can construct frequency tables. Listed below are some examples by which you can show distribution by:

- age and sex

- occupation

- location

- health status, e.g., underlying disease

- various exposures, such as

- procedures (e.g., type of surgery)

- food eaten, drugs used, types of disinfectants used

- use of invasive devices (endoscope, catheter, etc.).

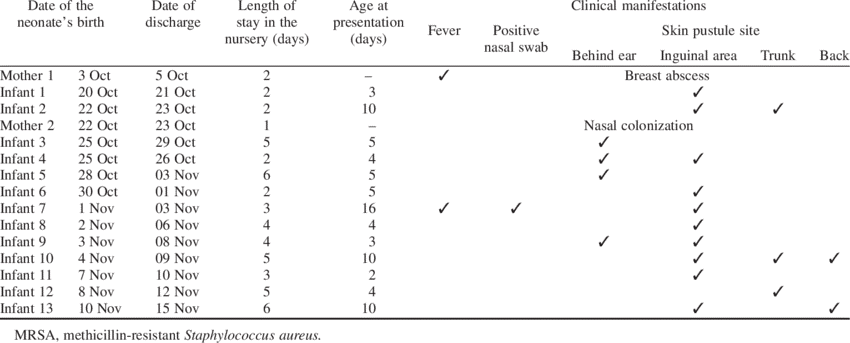

The line list3 below shows data collected during a MRSA outbreak (different from our case study). You may arrange the data in ascending or descending order by how often a certain data point appears.

Hover or tap to zoom

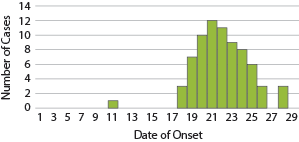

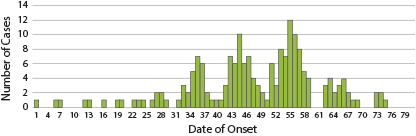

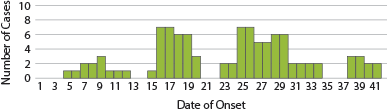

Epidemic curves (epi curves) are histograms displaying the number of cases in an outbreak by date of onset of illness. The shape of the resulting distribution of cases can provide information on:

In intervention epidemiology histograms are frequently used to present occurrence (distribution) of onsets of illness according to time. This is frequently called an epidemic curve even if it is not a curve.- when the exposure may have occurred;

- pattern of transmission;

- magnitude of the outbreak;

- incubation period/exposure;

- trend over time; and

- outliers (cases occurring very late or early in the outbreak), which can give clues about the origin of the outbreak or incubation period; they could represent a different outbreak wave.

Different sources for outbreaks result in different epi curve shapes. Click or tap the tabs below to learn more about what different epi curves mean.

Common Source Outbreak

A common source (point source) outbreak epi curve has:

- a single, short exposure

- a rapid increase in cases followed by slower decline

- all cases occurring within one incubation period.

Common Source Outbreak with Continuous Exposure

- Exposure is prolonged over an extended period of time.

- Cases are spread over more than one incubation period.

Some examples of common source outbreaks that may produce this epi curve are

- intrinsic contamination (at production) of parenteral nutrition, disinfectants, plasma, immunoglobulins, creams or peritoneal liquids

- extrinsic contamination (in use) of disinfectants, contrast media, heparin, multidose vials, anaesthetics, endoscopes or haemodialysis.

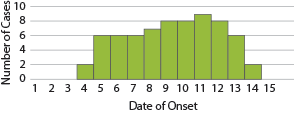

Propagated Outbreak

These epidemiological curves demonstrate outbreaks from both a propagated source and a common source with intermittent exposure. A propagated outbreak epi curve is characterized by:

- person-to-person transmission

- a pattern where the first wave of cases is the source for the second, which serves as the source for the following wave

- progressively higher peaks at the distance of one incubation period.

Common Source Outbreak with Intermittent Exposure

- Combination of point source and propagated outbreaks

- Point source followed by person-to-person transmission

Some examples of propagated source outbreaks include:

- Carrier: S. aureus, group A Streptococci, candida, hepatitis B and C, HIV, salmonella.

- Airborne: measles, chickenpox, tuberculosis.

- Droplets: adenovirus, influenza, pertussis, rubella, Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV), severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS).

- Environmental: Legionella, Aspergillus, Pseudomonas, Flavobacterium.

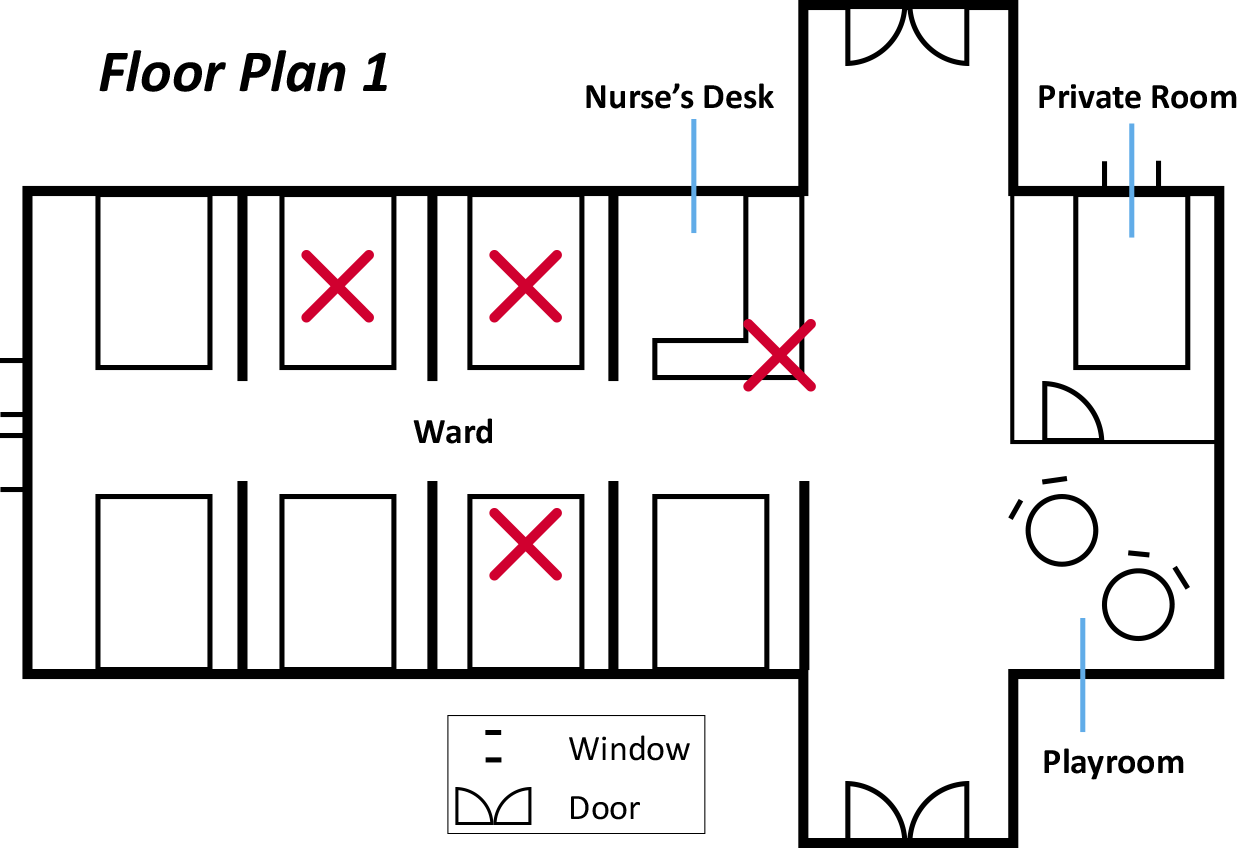

Using Spot Maps

Another way to analyse an outbreak is using a spot map. A spot map gives a visual representation of the spread of the outbreak and may provide clues as to how the infection was transmitted. To draw a spot map, create a floor plan of the affected unit/ward. Show the relationship of the areas where cases were identified by marking the areas where cases were found.

Do not forget to consider water sources, airflow and the position of ventilation systems; they may be important potential reservoirs or sources of transmission depending upon the outbreak. The image below is an example of a spot map. The x’s on the spot map represent the areas where cases have been identified.

Consider our example of the NICU unit to answer the following questions.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Summary (5 min)

In this module, you have learnt about describing an outbreak. These steps allow you to accurately define the case definition and epidemiology of an outbreak. Having a good description of an outbreak allows you to define new cases, gain information, assess data and look toward possible solutions.

When describing an outbreak, know that the first step can always be addressed with Step 9 of the process: implementing IPC strategies. When your team recognizes the existence of the outbreak, do not hesitate to act! Assess if any standard precautions or transmissions-based precautions need to be strengthened or put into place.

After your team has determined that there is an outbreak, the team will need to describe who is affected, how they have possibly come into contact with the disease, what the disease is and where the outbreak is occurring.

Using this hypothesis, your team can begin finding new cases of the outbreak using data collection methods. Organize this data into epi curves that describe the epidemiology of the outbreak. You will interpret this data during the analysis phase of the investigation.

-

References

- Irfan S, Ahmed I, Lalani F, Anjum N, Mohammad N, Owais M, et al. Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus outbreak in a neonatal intensive care unit. East Mediterr Health J. 2019 Oct 4;25(7):514518. doi: 10.26719/emhj.18.058. PubMed PMID: 31612983.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Principles of epidemiology in public health practice. 3rd ed. [updated 2011 Nov]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006 (https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section5.html, accessed 20 Nov 2019).

- Alsubaie S, Bahkali K, Somily AM, Alzamil F, Alrabiaah A, Alaska A, et al. Nosocomial transmission of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in a well-infant nursery of a teaching hospital. Pediatr Int. 2012 Dec;54(6): 78692. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-200X.2012.03673.x. PubMed PMID: 2264061.