Identifying a HAI Outbreak

Many of the precautions that should be put in place in a health care facility to prevent health care acquired infections (HAI) or reduce antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are critical to protect patients, health care workers (HCWs) and visitors from epidemic spread of pathogens. When an outbreak occurs within the facility, it is the responsibility of the infection prevention and control (IPC) team to help identify and investigate the source of that outbreak, reduce its effects and, with the support of the broader outbreak team, prevent its recurrence. The IPC team should also be able to assess when there is a risk of spread of a pathogen brought into the facility from the community, and should put in place measures to prevent or contain health care-associated transmission. In this module you will learn how to identify a HAI outbreak in your facility and what to do after a HAI outbreak is identified. Much of the content in this module will draw from other modules in this course. Take note of these referrals and seek out the other modules for more information.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module you will be able to:

- define an outbreak and describe the various types that occur within a health care setting;

- identify how levels of disease occurrence dictate epidemiology of disease in a population; and

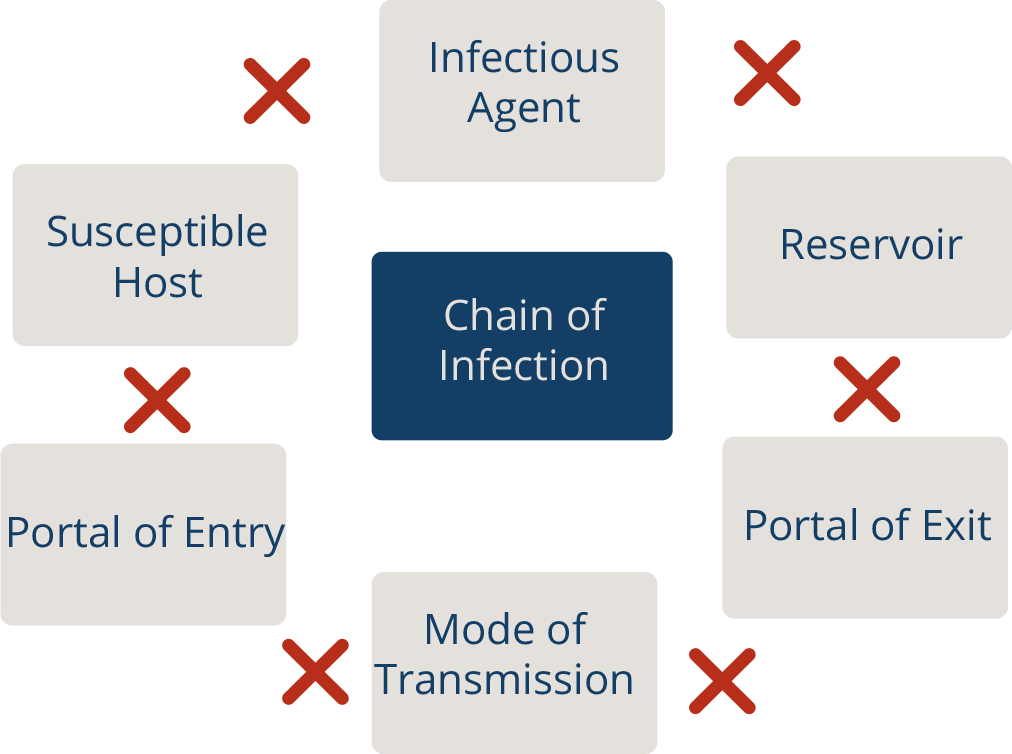

- describe how breaking the chain of infection can help prevent or stop an outbreak.

Learning Activities Estimated time:

-

The Role of IPC in an Outbreak (10 min)

In this module you will learn how to identify a HAI outbreak, which is different from a typical outbreak. The definitions below illustrate this distinction. In this course we will focus on a HAI outbreak.

Epidemic refers to an increase, often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area. Outbreak carries the same definition of epidemic, but is often used for a more limited geographic area.1

Outbreaks of HAI are defined as hospital-associated or health care facility-associated infections among patients or staff that represent an increase in incidence over expected background rates.2

A HAI outbreak occurs when HAIs or adverse events occur above the background rate or when an unusual microbe or adverse event is recognized.3

Standard precautions and transmissions-based precautions provide the IPC professional with tools that help break the chain of infection. Breaking this chain can stop the spread of HAI and reduce AMR. As you learn about how to identify and investigate HAI outbreaks, you will learn how these precautions apply to stop and prevent them.

Consider your role as an IPC professional during a HAI outbreak. Use this knowledge to think about the following questions. Write your responses in a notebook or the text boxes below. Click or tap the “Compare Answer” button to see an expert’s response.

-

Defining an Outbreak (10 min)

For IPC personnel, it is important to be able to identify if an outbreak is occurring in the first place. There are a few definitions that will help you distinguish whether the occurrence of a disease indicates a true outbreak. The presence of a HAI outbreak may represent an increase in incidence over expected background rates. The indicators of outbreaks can be categorized by when and where the incident occurs, the sources identified and other health care associated factors.

Before we go any further, it is important that we make a few distinctions in terminology. Click or tap the tabs below to learn more about how an outbreak is categorized:

Cluster

A cluster refers to an aggregation of cases grouped in place and time that are suspected to be greater than the number expected, even though the expected number may not be known.1 Even if the increase in number of cases is not more than is expected for a given population, the presence of these disease cases is still defined as a cluster. The term cluster is sometimes used to refer to a small outbreak; however, a small outbreak should be regarded as distinct from a true outbreak because the number of cases involved is likely due to chance or is not more than would be expected. Regardless of the source of infection, a cluster needs to be investigated within the health care setting and appropriate action taken, if required.

Example: A health care facility has a baseline rate of four cases of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) per quarter but notes an increase of three cases in the first month of quarter one. Although this is not above the usual expected rate for this facility, this would still require investigation to be sure nothing more serious is brewing.

Outbreak

An outbreak can be described as a group of cases that are linked by both time and place. These disease cases are usually suspected to come from a common source of infection. They can be:

- a greater than expected incidence of infection compared to the usual background rate for the particular facility or ward;

- a single case for certain rare or epidemic prone diseases;

- a suspected, anticipated or actual event involving microbial contamination of food or water (e.g., sink drains, water reservoirs).

Regardless of the source, an outbreak must be investigated within the health care setting. It is also important to note that some countries may have national or state level definitions that predefine health care associated outbreaks by specific organisms and thus must be followed.

Example: A patient in a four-bed room is admitted with influenza-like illness. After an investigation, this patient is identified to be influenza A positive. Subsequently, three additional cases arise on the unit who have been admitted to the unit for more than two weeks already. This would be an example of an influenza outbreak given the link in location and time.

Pseudo-outbreak

A pseudo-outbreak is not a true outbreak. It is defined by an increased number of reported cases which may be caused by several factors. These factors include:

- changes in health care staff or practices

- a change in case definition in the context of surveillance

- a change in sampling procedures or laboratory techniques.

Example: A new testing methodology is introduced in the laboratory. The new test is more sensitive and specific for certain organisms than your surveillance program currently tracks. Subsequently, there is an increase in positive laboratory results for the targeted organism. This may appear as though there is an outbreak, when, in fact, the increase in reported positives is related to the new testing methodology. Surveillance processes will need to be reviewed and a new baseline rate may need to be established for the specific organism.

Now that you are more familiar with key terminology, let us test your knowledge with the questions below. Read each scenario and use the slider to answer the question “Is it an outbreak?”

Scenario 1

You are reviewing your surveillance data and notice a sharp increase in the number of hospital-acquired MRSA cases in one ward of your facility. It is typical that the ward identifies two cases of MRSA per month. However, over the past several weeks, there have been two cases every week. When investigating daily activities in the ward, you notice inconsistent hand hygiene practices among some personnel. You also note that several of the cases recorded were patients sharing a room.

Scenario 2

Recently, you worked with the emergency department to implement a new tool for identifying patients presenting with influenza-like illness to prompt earlier isolation. Over the next week you notice an increase in the number of patients being isolated for respiratory illnesses.

Scenario 3

A hospital usually has six hospital-acquired tuberculosis (TB) cases per quarter; however, four new TB cases have been identified in the past month alone. Is this an outbreak?

-

Levels of Disease Occurrence (5 min)

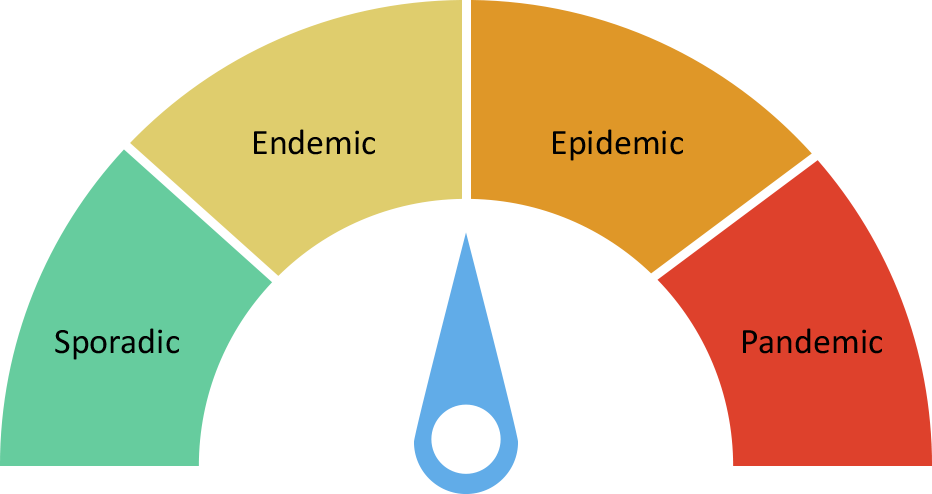

Different levels of disease occurrence are reflective of how common (endemic) a disease is in a population. The level of occurrence dictates how the outbreak is investigated. Click or tap the graphic below to learn more about each level of disease occurrence.

Sporadic

A sporadic disease occurs infrequently and irregularly amongst a population. For example, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a viral respiratory disease. It occurs infrequently and is often associated with travel or close contact with camels. Case numbers rise and fall depending upon seasons, events and other contextual factors.

Endemic

Endemic is defined as “the constant presence and/or usual prevalence of a disease or infectious agent in a population within a geographic area”.1 Now, using our example of MERS-CoV, let us assume cases are more expected and no longer only tied to travel or interactions with camels. A country will expect to see a certain number of cases that fall within an expected range over a quarterly or annual period.

Epidemic

Epidemic is defined as an increase, which is often sudden, in the number of cases of a disease above what is normally expected in that population in that area. An epidemic is typically more prolonged and widespread than an outbreak.1 An example of a MERS-CoV epidemic is if the number of cases were to rise rapidly during a period of time, spreading to an increased number of people in a population (and, in some cases, to other countries as well).

Pandemic

Pandemic is defined as a global epidemic that spreads in several countries or continents, usually affecting a large number of people.1 If MERS-CoV cases rose exponentially and spanned continents, this outbreak could potentially be declared a pandemic. It is important to note that WHO is the authority and official organization that can declare a true pandemic.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

How Pathogens Are Transmitted (15 min)

So far, we have defined what an outbreak is, key terms and the levels of disease occurrence. Now we will revisit how a disease is transmitted. The Introduction to IPC module covered the chain of infection illustrated in the graphic below. Click or tap each link of the chain to read more about how it contributes to the spread of disease.

Infectious Agent

An infectious agent or microorganism capable of causing infection, such as a virus, bacteria, or other microbe.

Reservoir

The reservoir is where microorganisms can be found. This can be a person (patient or health worker) or the environment. The health care environment contains diverse microorganisms. Environmental sources include dry surfaces (bed rails and medical equipment), wet surfaces (faucets, sinks, and ventilators), indwelling medical devices (catheters and IV lines), and the environment surrounding the patient. All of these sources can serve as reservoirs for pathogens.

Portal of Exit

Microorganisms must exit their reservoir in order to spread. For example, when someone coughs, microorganisms leave the reservoir (the person) through the respiratory tract. Portals of exit can include breaks in skin, mucous membranes (eyes, nose, and mouth), hands, blood, and gastrointestinal and urinary tracts (faeces, vomit, and urine).

Mode of Transmission

Microorganisms need a way to move (spread) from the portal of exit to the portal of entry. In other words, microorganisms need a way to get from point A to point B. Microorganisms usually depend on people, the environment, and medical equipment to move in health care settings.

- Direct

- Direct contact

- Droplet spread

- Indirect

- Airborne

- Vehicleborne

- Vectorborne (mechanical or biologic)

In direct transmission, an infectious agent is transferred from a reservoir to a susceptible host by direct contact or droplet spread.

- Direct contact occurs through skin-to-skin contact. Direct contact also refers to contact with soil or vegetation harboring infectious organisms.

- Droplet spread refers to spray with relatively large, short-range aerosols produced by sneezing, coughing, or even talking. Droplet spread is classified as direct because of transmission by direct spray over a few feet, before the droplets fall to the ground.

Indirect transmission refers to the transfer of an infectious agent from a reservoir to a host by suspended air particles, inanimate objects (vehicles), or animate intermediaries (vectors).

- Airborne transmission occurs when infectious agents are carried by dust or droplet nuclei suspended in air. Airborne dust includes material that has settled on surfaces and become resuspended by air currents as well as infectious particles blown from the soil by the wind. In contrast to droplets that fall to the ground within a few feet, droplet nuclei may remain suspended in the air for long periods of time and may be blown over great distances.

- Vehicles that may indirectly transmit an infectious agent include food, water, biologic products (blood), and fomites (inanimate objects such as handkerchiefs, bedding, or surgical scalpels).

- Vectors such as mosquitoes, fleas, and ticks may carry an infectious agent through purely mechanical means or may support growth or changes in the agent.

Portal of Entry

Devices like IV catheters and surgical incisions can provide an entryway for microorganisms to gain access to a susceptible host. Mucous membranes (eyes, nose, and mouth) are an entryway for microorganisms spread by direct contact, sprays, splashes, and inhalation. Breaks in the skin, such as a puncture caused by a sharps injury, can also be an entryway for microorganisms. Notice that portals of entry may also serve as portals of exit and reservoirs for harmful microorganisms.

Susceptible Host

The final link in the chain is the susceptible host. The final link in the chain is the susceptible host. When patients receive medical treatment in healthcare facilities, the following factors can increase their susceptibility to infection:

- Patients who have underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and organ transplantation are at increased risk for infection. These illnesses often decrease the immune system’s ability to fight infection.

- Certain medications used to treat medical conditions, such as antibiotics, steroids, and some chemotherapy medications, increase the risk of some types of infections.

- Medical devices and procedures such as urinary catheters, tubes, and surgery, increase risk of infection by providing additional ways that microorganisms can enter the body.

Use what you know about the chain of infection to fill in the blanks.

For more information about the chain of infection take the Introduction to IPC module.

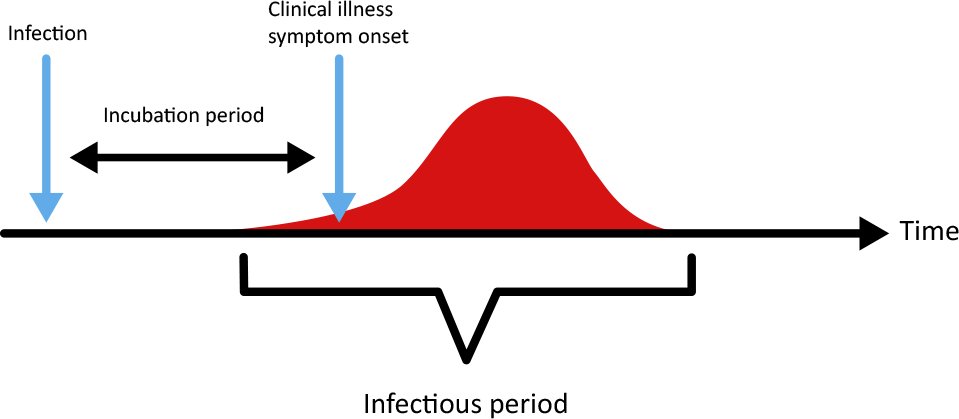

The Incubation and Infectious Period

Understanding how a disease is transmitted is only part of the story. You must also know when the disease was transmitted. The graphic below illustrates the incubation period, which is the time between the exposure to an infectious agent and the onset of symptoms. For a chronic disease, this is referred to as the latency period. The infectious period is the time when an infected person can transmit a pathogen.

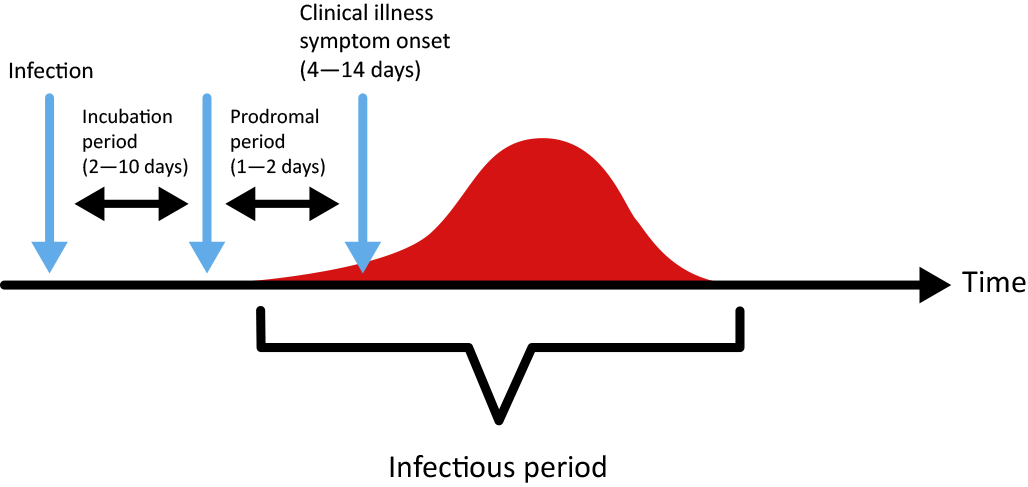

The periods of time before the onset of symptoms are very important in the dynamics of disease spread because they dictate when cases will be detected relative to the time of infection and the incubation period. As you can see in the graphic below, in some instances, transmission can occur before clinically specific symptoms appear. This is called the prodromal period. The infectious period can occur as soon as one to two days after infection.

Prodromes or prodromal symptoms are early AND non-specific for diagnosis.

To help illustrate the prodromal period, let us look at an example: a patient coming down with a case of chicken pox. During the incubation period, the patient often develops prodromal symptoms of a fever or a runny nose before the actual blisters erupt. The disease is in the body and shows early signs and symptoms before symptoms specific to the disease arise.

- Direct

-

The Swiss Cheese Model (5 min)

What are some factors that might lead to an outbreak in your facility? Imagine if:

- the alcohol-based handrub (ABHR) was never restocked

- all patients had to share one functional bathroom on the floor

- the cleaning staff stopped cleaning.

It’s possible for two or more of these situations to occur at one time in a health care facility. When factors like these frequently occur, the defense barrier preventing an infectious organism from spreading will weaken. The presence of such vulnerabilities can lead to an outbreak.

The Swiss Cheese Model

This model allows us to see that if too many challenges stack up, infectious organisms capable of causing outbreaks will spread and potentially cause devastation and harm. There might be a defect in infrastructure such as poor sanitation or a lack of isolation facilities, ABHR or water. Alone, these infrastructure deficiencies are harmful but might not necessarily cause an outbreak. However, if these defects are coupled with other issues, the result could be a catastrophic outbreak.

In the animation below, the path that the arrow takes represents the infectious agent. Each hole in the slices of cheese represents a defect in the facility. As these holes align, the infectious agent can spread more easily.

An outbreak is usually a result of a combination of these defects or errors coming into alignment. Imagine that a patient with a MRSA-infected wound is admitted into a busy ward. At this hospital, IPC practices have not been regularly monitored. There are only a few hand washing stations and no ABHR, resulting in a culture of poor hand hygiene. While the more immediate problem is poor hand hygiene practices, further analysis reveals defects at various levels.

In order to identify these gaps and stop the possibility of an outbreak, a multimodal approach is needed. You will learn more about how to apply the multimodal approach later in the Outbreak Investigation portion of this module.

-

Patterns of Transmission (5 min)

Another component of identifying an outbreak is recognizing the patterns of transmission, that is, describing the source from which a disease originated. Understanding these patterns will help you to understand how to break the cycle of transmission and prevent or end an outbreak.

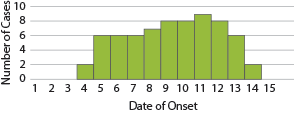

Common source

A common source indicates a single point source. This means the exposure period is usually brief, and all cases acquired the infection from the same origin and in one incubation period. A single person or vehicle, such as contaminated food or equipment, can be identified as the source. A contaminated water source may spread cholera or typhoid. A HCW colonized with MRSA may spread the bacteria to their patients.

Additionally, there are subsets within common source patterns. These are:

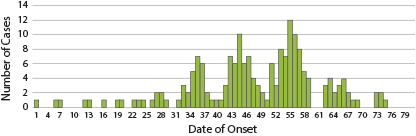

- Continuous common source: In this type of outbreak, exposures to the sources continue over a period of days,weeks or even longer. Continuous common-source exposure will often cause cases to rise gradually (and possibly plateau, rather than peak). Continuous common-source exposure will often cause cases to rise gradually (and possibly plateau, rather than peak).

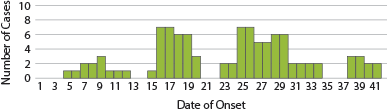

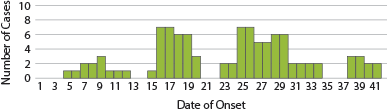

- Intermittent common source: An intermittent exposure in a common-source outbreak often results in an epi curve with irregular peaks that reflect the timing and extent of the exposure. An example is bacteraemia associated with contaminated blood product.7

Propagated

Propagate transmission is when there is ongoing transmission of infection from person-to-person in steadily increasing numbers, usually separated by an interval of time and always over more than one incubation period. While the infection is passed on from a vulnerable host, it does not originate from a single source.1 Examples of this are the Ebola outbreaks, the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and measles.

Mixed source

Mixed epidemics have features of both common source epidemics and propagated. They will often have the pattern of a common source outbreak that is followed by secondary person-person spread.1

Common Outbreaks and Sources

As you begin to consider the patterns of disease transmission, it can be helpful to look to the literature to help inform what is most commonly identified in certain settings or care areas. The tables below describe the most common outbreaks and sources to occur in a health care setting:

Site of infection Frequency Bloodstream infections 37% Gastrointestinal tract infections 29% Pneumonia 23% Urinary tract infections 14% Surgical site infections 12% Other lower respiratory tract infections 10% Central nervous system infections 8% Skin and soft tissue infection 7% According to this table, 37% of health care associated outbreaks are bloodstream infections, followed by gastrointestinal tract infections and pneumonia.6 Think about the chain of transmission to consider how these infections may be occurring. For example, following best practices for hand hygiene, line insertion and maintenance, and safe injection can reduce the risk of bloodstream infections.

It is important to note that in many cases, a source may not be identified. This is evident in the table below, which shows 37% of outbreaks reviewed did not have a source identified. One reason for this is the importance placed on stopping the outbreak and instituting enhanced IPC, which will often undercut the ability to decisively determine the cause.

Source Frequency No identified sources 37% Patient 22.8% Medical equipment or devices 11.9% Environment 11.6% Staff 10.9% Contaminated drugs 3.6% Contaminated food 3.3% Contaminated care equipment 3.2% In the next activity, you will learn about breaking the chain of infection.

- Continuous common source: In this type of outbreak, exposures to the sources continue over a period of days,weeks or even longer. Continuous common-source exposure will often cause cases to rise gradually (and possibly plateau, rather than peak). Continuous common-source exposure will often cause cases to rise gradually (and possibly plateau, rather than peak).

-

Breaking the Chain of Infection (10 min)

Part of the role of the IPC team is to strategize ways to break the chain of infection. The rest of this module will expand upon how each link of the chain is broken. Click or tap each link to read methods in how to break it.

Infectious Agent

An infectious agent or microorganism capable of causing infection, such as a virus, bacteria or other microbe.

How to break the link:

The activity needed to break the link of the infectious agent is surveillance. Rapid, accurate identification of the microorganism(s) will help determine how to stop the spread of the organism(s) (i.e., prompt isolation according to the mode of transmission). Refer to the Surveillance module and the Microbiology module to learn more about identification of microorganisms.

Reservoir

The reservoir is where microorganisms can be found. This can be a person (a patient or HCW) or the environment. The health care environment contains diverse microorganisms. Environmental sources include dry surfaces (bed rails and medical equipment), wet surfaces (faucets, sinks and ventilators), indwelling medical devices (catheters and IV lines) and the environment surrounding the patient. All of these sources can serve as reservoirs for pathogens.

How to break the link:

The reservoir represents the environment of the health care system, from equipment to HCWs and patients. Ensure that HCWs have proper training and reminders about

- occupational health

- environmental hygiene

- WASH and cleaning

- disinfection and sterilization practices.

Water, sanitation and hygieneTake the Environmental Cleaning and Decontamination and Sterilization modules to learn more.

Portal of Exit

Microorganisms must exit their reservoir in order to spread. For example, when someone coughs, microorganisms leave the reservoir (the person) through the respiratory tract. Portals of exit can include breaks in skin, mucous membranes (eyes, nose and mouth), hands, blood, and gastrointestinal and urinary tracts (faeces, vomit and urine).

How to break the link:

The portal of exit is the location from which a harmful microorganism exits a reservoir or host. It is important that health care facilities properly implement standard precautions. This includes proper hand hygiene, waste management, use of personal protective equipment (PPE) and cough etiquette. Refer to the Standard Precautions and PPE modules to learn more.

Mode of Transmission

Microorganisms need a way to move (spread) from the portal of exit to the portal of entry. In other words, microorganisms need a way to get from point A to point B. Microorganisms usually depend on people, the environment and medical equipment to move in health care settings.

How to break the link:

Modes of transmission can be direct or indirect contact, droplets or airborne transmission. Transmission-based precautions prevent the spread of disease by these modes. Such measures include enforced hand hygiene, patient placement/isolation according to the mode of transmission, safe food handling and air flow control.

Refer to the Introduction to IPC and Transmission-Based Precautions modules to learn more about these modes of transmission.

Portal of Entry

IV catheters, surgical incisions and the like can provide an entryway for microorganisms to gain access to a susceptible host. Mucous membranes (eyes, nose and mouth) are an entryway for microorganisms spread by direct contact, sprays, splashes and inhalation. Breaks in the skin, such as a puncture caused by a sharps injury, can also be an entryway for microorganisms. Notice that portals of entry may also serve as portals of exit and reservoirs for harmful microorganisms.

How to break the link:

In a health care setting, the potential for cuts, wounds and devices to serve as a portal of entry for harmful microorganisms is high. HCWs should be educated on the principles of asepsis, and procedures should be standardized throughout the facility.

Susceptible Host

When patients receive medical treatment in health care facilities, the following factors can increase their susceptibility to infection:

- Patients who have underlying medical conditions such as diabetes, cancer or organ transplantation are at increased risk for infection. These conditions often decrease the immune system’s ability to fight infection.

- Certain medications used to treat medical conditions, such as antibiotics, steroids and some chemotherapy medications, increase the risk of some types of infections.

- Medical devices and procedures, such as urinary catheters, tubes and surgery, increase the risk of infection by providing additional ways that microorganisms can enter the body.

How to break the link:

In your facility, it is important to consider the population being served. Be vigilant of high-risk patients. Those with underlying medical conditions or poor nutrition can be particularly susceptible. Ensure timely and effective treatment of disease where possible.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Summary (5 min)

In this module you have learned how to identify a HAI outbreak. You’ve learned that the difference between a HAI outbreak and other outbreaks is that a HAI outbreak originates from a common source and spreads among the health care facility. In order to identify whether an outbreak is occurring, the time and place of the cases must be considered. A pseudo-outbreak can be misidentified as an outbreak due to a change in protocol, staff, or policy.

When an outbreak is identified, it should be categorized. We use the terms sporadic, endemic, epidemic, and pandemic to describe the levels of disease occurrence for a given population. The level of disease occurrence dictates how the investigation should be conducted. When you understand the level of disease occurrence, you can then analyse how the disease was spread. The chain of infection will help you to identify modes of transmission and possible sources.

As an IPC professional, it is your job to understand how to break the chain of infection at every level to stop or prevent an outbreak. Correctly and consistently implementing standard precautions and transmissions-based precautions at your facility will reduce HAI outbreaks.

-

References

- Gregg M. Field epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/978019531802.001.0001.

- Srinivasan A, Jarvis W. Outbreak investigations. Lautenbach E, Woeltje KF, Malani P, editors. Practical healthcare epidemiology. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2010.

- Srinivasan A. Outbreak investigation. In: Carrico R, Adam L, Aureden K, Fauerbach L, Friedman C, editors. APIC text of infection control and epidemiology. Volume 1. 3rd ed. Washington (DC): APIC; 2009. pp. 4.1¬4.10.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Principles of epidemiology in public health practice. 3rd ed. [updated 2011 Nov]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006 (https://www.cdc.gov/csels/dsepd/ss1978/lesson1/section11.html, accessed 20 Nov 2019).

- Rasmussen SA and Goodman RA. The CDC Field Epidemiology Manual. New York: Oxford University Press, 2019. https://www.cdc.gov/eis/field-epi-manual/chapters/Healthcare-Settings.html

- Gastmeier P, Stamm-Balderjahn S, Hansen S, Nitzschke-Tiemann F, Zuschneid I, Groneberg K, et al. How outbreaks can contribute to prevention of nosocomial infection: analysis of 1,022 outbreaks. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2005;26(4):357–61. doi:10.1086/502552. PubMed PMID: 15865271.

- Rasslan, Ossama. Outbreak Management. Chapter 5. http://theific.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/5-Outbreak_2016.pdf