Overview of Surgical Site Infections

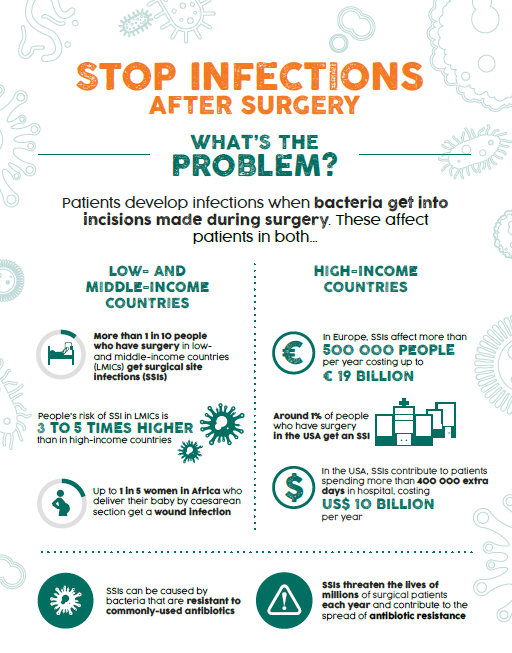

Surgical site infections (SSI) are a serious problem globally; they are the most frequent type of health care-associated infection (HAI) observed on admission in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Approximately one in 10 people who have surgery in LMICs acquire an SSI, and SSI is reported as the second most common HAI in Europe and the United States of America. Therefore, it is crucial to include SSI prevention activities in your overall IPC programme.

This first section of this SSI module will cover global SSI rates, the importance of understanding the burden of SSI in your facility, or in facilities in your country, and how the World Health Organization’s (WHO) core components support implementing SSI prevention measures as part of IPC programmes. If you have not yet taken the WHO Core Components and Multimodal Strategies module, we recommend taking it before proceeding with this module.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- describe the interconnection between SSI prevention and overall IPC efforts, and how preventing SSI should be a critical part of a strong, effective IPC programme; and

- describe and explain the burden and epidemiological factors that influence SSI, understand of the importance of reviewing existing and emerging data to aid SSI reduction within the local context.

Learning Activities

-

Trang & Dinh (10 min)

In Vietnam, Trang has a caesarean section (C-section) to deliver her second child. While she is in the hospital, her wound becomes infected. It seems to Dinh, the IPC specialist at the hospital where Trang had her C-section, that there have been a lot of cases with signs and symptoms of post-surgical infection lately. Dinh wonders if this situation is unique, and wants to look at data from other sites. Could this be a genuine problem at his facility?

Take a moment to think about what the top three challenges are in identifying and preventing surgical site infections at your facility. If you don’t know what those challenges might be for your facility, or if you don’t work in a facility, think about what they might be for Dinh’s facility. Type them in the boxes below.

-

Introduction to SSI (5 min)

Surgical site infections (SSI) refer to infections that occur after surgery in the part of the body where surgery was performed. SSI can sometimes be superficial, involving the skin only. Other SSI are more serious, and can involve tissues under the skin (for example, muscle layers), organs, or implanted material.

SSI is a problem that occurs in all countries, but can be avoided through safe surgical practices. SSI prevention measures are a crucial part of overall infection prevention.

-

SSI Case Definitions (5 min)

Let us look at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) definitions of SSI, which shows the kinds of infections that can occur, and where they can occur.

Click or tap on each “zone” of the image to read about the signs and symptoms of infection and the case definitions.1

Superficial incisional SSI

Date of event for infection occurs within 30 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date)

and

involves only the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the incision

and

patient has at least one of the following:

- Purulent drainage from the superficial incision.

- Organisms identified from an aseptically-obtained specimen from the superficial incision or subcutaneous tissue by a culture or non-culture-based microbiologic testing method which is performed for the purpose of clinical diagnosis or treatment.

- Superficial incision that is deliberately opened by a surgeon, attending physician, or other designee and culture or non-culture based testing is not performed.

and

patient has at least one of the following signs or symptoms: pain or tenderness, localized swelling, erythema, or heat. - Diagnosis of a superficial incisional SSI by the surgeon, attending physician, or other designee.

Deep incisional SSI

The date of event for infection occurs within 30 or 90 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) according to Surveillance Periods for SSI Following Selected NHSN Operative Procedure Categories

The date of event for infection occurs within 30 or 90 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) according to the Surveillance Periods for SSI Following Selected NHSN Operative Procedure Categories in the Resources Section.

and

involves deep soft tissues of the incision (for example, fascial and muscle layers)

and

patient has at least one of the following:

- Purulent drainage from the deep incision.

- A deep incision that spontaneously dehisces; or is deliberately opened or aspirated by a surgeon, attending physician, or other designee;

and

a previously closed wound reopeningthe organism is identified by a culture or non-culture based microbiologic testing method which is performed for purposes of clinical diagnosis or treatment or culture or non-culture based microbiologic testing method is not performed;and

patient has at least one of the following symptoms: fever (> 38º C); localized pain or tenderness. A culture or non-culture based test that has a negative finding does not meet this criterion. - An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the deep incision that is detected on gross anatomical or histopathologic exam or imaging test.

Organ/space SSI

Date of event for infection occurs within 30 or 90 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) according to Specific Sites of an Organ/Space SSI

Date of event for infection occurs within 30 or 90 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) according to the Specific Sites of an Organ/Space SSI in the Resources Section

and

infection involves any part of the body deeper than the fascial/muscle layers that is opened or manipulated during the operative procedure

and

patient has at least one of the following:

- Purulent drainage from a drain that is placed into the organ/space (for example, closed suction drainage system, open drain, T-tube drain, CT guided drainage).

- Organisms are identified from fluid or tissue in the organ/space by a culture or non-culture based microbiologic testing method which is performed for purposes of clinical diagnosis or treatment.

- An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the organ/space that is detected on gross anatomical or histopathologic exam, or imaging test evidence suggestive of infection.

and

meets at least one criterion for a specific organ/space infection site (see Resources section for Specific Sites of an Organ/Space SSI).and

meets at least one criterion for a specific organ/space infection site (Specific Sites of an Organ/Space SSI).

-

Wound Classification (5 min)

Another helpful classification guide is the CDC’s surgical wound classification.1 This guide helps clinicians describe the degree of bacterial contamination of various surgical wounds. Clinicians can use this classification to gauge the risk of potential complications such as SSI in surgical procedures.

Click or tap on each classification to read its description.

Clean

Clean wounds are uninfected operative wounds in which no inflammation is encountered, and the respiratory, alimentary, genital, or uninfected urinary tracts are not entered. In addition, clean wounds are primarily closed and, if necessary, drained with closed drainage. Operative incisional wounds that follow non-penetrating (blunt) trauma should be included in this category if they meet the criteria.

Clean-contaminated

Clean-contaminated wounds are operative wounds in which the respiratory, alimentary, genital, or urinary tracts are entered under controlled conditions and without unusual contamination. Specifically, operations involving the biliary tract, appendix, vagina, and oropharynx are included in this category, provided no evidence of infection or major break in technique is encountered.

Contaminated

Contaminated wounds are open, fresh, accidental wounds. In addition, operations with major breaks in sterile technique (for example, open cardiac massage) or gross spillage from the gastrointestinal tract, and incisions in which acute, non-purulent inflammation is encountered including necrotic tissue without evidence of purulent drainage (for example, dry gangrene) are included in this category.

Dirty or infected

Dirty or infected wounds include old traumatic wounds with retained devitalized tissue, and those that involve existing clinical infection or perforated viscera. This definition suggests that the organisms causing postoperative infection were present in the operative field before the operation.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Global Burden of SSI (5 min)

Let us now look at the magnitude of the problem of SSI worldwide. Understanding what SSI rates are globally will help you explain to your colleagues, managers, and administrators the common problems that are likely to occur in your facility. The purpose of these statistics is not for you or others to memorize or analyse, but rather to help you describe and summarize. Presenting these statistics can motivate others to engage in improvement activities.

Many statistics in this section are from a global report published by WHO in 2011,2 two scientific papers,3,4 and unpublished WHO information.5 The WHO report focused on the global burden of health care-associated infections (HAI) overall. The two scientific papers looked more specifically at the problem in LMICs.

WHO updated its analysis of the incidence of SSI in LMICs based on published studies between 1995 and 2015, and reported average incidence rates of 5.9 per 100 surgical procedures and 11.2 per 100 surgical patients (WHO unpublished data, 2017).5 The most frequent pathogens are usually Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) and Escherichia coli. The average methicillin (antibiotic) resistance among S. aureus is 54.5%, which is of concern when trying to treat some types of SSI.2,3 Additionally, it is estimated that 30% of all cases of sepsis are from surgical procedures.6

By contrast, SSI rates range from 0.6% to 9.5% in Europe and the USA.7,8 SSI are the second most frequent type of infection overall in high-income countries. Incidence varies according to the type of procedure. S. aureus is one of the most frequent causes of SSI (varying from 17% to 30% of cases).8 In the USA, 39–51% of SSI pathogens may be resistant to SSI prophylactic antibiotics, making it harder to prevent these infections in the first place.9

-

Burden of SSI in LMICs (5 min)

According to the above-mentioned WHO systematic review updated in 20175, SSI resulting from specific procedures that are meant to be clean, such as C-sections and prosthetic orthopaedic surgeries, occur more frequently in LMICs than in high-income countries. For instance, in LMICs, SSI rates are 11.7% for C-sections (with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of 9.1–14.8), and 9.7% for prosthetic orthopaedic surgery (95% CI of 5.3–15.3). Compare this with Europe, where SSI rates are 2.2% for C-sections (inter-country range from 0.6% to 7.7%), 0.6% for knee operations (inter-country range from 0.0% to 3.4%), and 1.1% for hip replacements (inter-country range from 0.3% to 3.8%).7

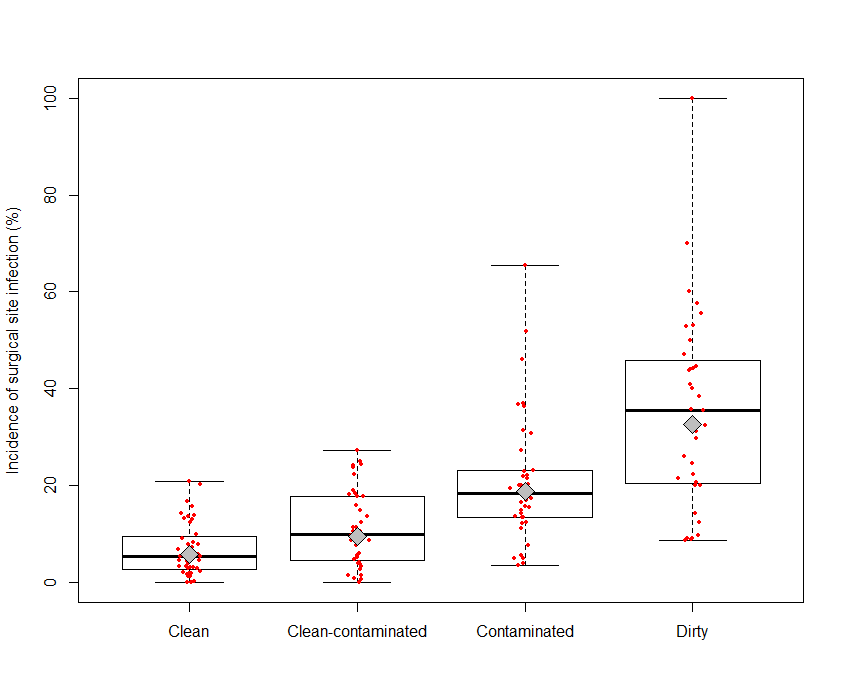

Additionally, according to the updated WHO analysis,5 SSI incidence pooled mean (per 100 surgical procedures) according to the wound classification are

- 5.8% for clean wounds

- 9.5% for clean-contaminated wounds

- 18.9% for contaminated wounds

- 32.7% for dirty wounds

The graph below outlines these results.

Limited data are available about the burden of SSI in LMICs. This table lists some studies that have reported mortality, length of stay (LOS), and costs for a range of surgeries. Some of the studies specifically note the differences between LOS with and without an SSI. While death did not always occur, SSIs still are an avoidable burden on patients and the health care system.

Author, year, country Population LOS, days Mortality Costs Ameh, 2009, Nigeria Paediatrics 26.1 (8-127) with SSI vs 18.0 (1-99) without 10.5% vs 4.1% NA Bhatia, 2003, India Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) LOS significantly higher (mild 15, moderate 20, severe 25) No SSI related deaths Increased by 3.8%, 14.7%, and 29.4% in mild, moderate, severe infections Raka, 2007, Kosovo (in accordance with Security Council resolution 1244 (1999)) Abdominal surgery 9 with SSI vs 4 without NA NA Kasatpibal, 2005, Thailand Mixed surgery Mean excess LOS: 21.3 Mean excess cost: US$1355 Kaya, 2006, Turkey General surgery Mean excess LOS: 8 NA Mean excess cost: US$600 Le, 2006, Vietnam Orthopaedics and neurosurgery Mean excess LOS: 18 No mortality difference NA -

SSI at Your Facility (10 min)

Given what you know about the burden of SSI globally, take a moment to think:

- Do you (or others) think that SSI is a problem in your setting? If yes, how big is the problem?

- In your estimate, how many patients out of 100 surgical patients in your facility contract an SSI?

- Do you (or others) know how well staff adhered to safe practices in those cases? How aware are staff of what these safe processes (effective SSI prevention measures) are?

-

Surveillance (5 min)

In addition to knowing the burden of SSI worldwide, we need to be aware of the extent of the problem at our own facilities if we are to convince others to support SSI prevention efforts. To do this, we should conduct surveillance activities.

Surveillance is the ongoing systematic collection, analysis, interpretation, and evaluation of health data, closely integrated with the timely dissemination of these data to those who need it. Conducting high-quality SSI surveillance is crucial to detect the magnitude of the problem, and to assess the impact of any prevention/improvement interventions.

The protocol for surgical site infection surveillance with a focus on settings with limited resources (Protocol for Surgical Site Infection Surveillance) has more information about how to conduct surveillance using a WHO approach for SSI surveillance. Though targeted to settings with limited resources, this protocol is applicable to all countries. We will not cover how to conduct surveillance for SSI in this module. Instead, we will provide a brief overview about the importance of conducting surveillance, and how it can help you reduce SSI rates.

The protocol for surgical site infection surveillance with a focus on settings with limited resources (which is available in the Resources section) has more information about how to conduct surveillance using a WHO approach for SSI surveillance. Though targeted to settings with limited resources, this protocol is applicable to all countries. We will not cover how to conduct surveillance for SSI in this module. Instead, we will provide a brief overview about the importance of conducting surveillance, and how it can help you reduce SSI rates.

When conducting surveillance and gathering data on SSI, it is important that you consider what improvements can be made at your facility. Based on the data, consider the importance of prioritizing the improvement that is most likely to have the greatest impact. Which areas of surgery could be starting points for making improvements to ensure SSI prevention, patient safety, and better quality of care? Choose interventions that are measurable and applicable, and where progress can be clearly demonstrated over time, against prevalence or incidence (surveillance) results. You should report on practices and SSI rates in your facilities. We will return to surveillance when we talk about improvement actions in the third section.

Recognizing that surveillance is challenging and demanding, especially when human resources and time are limited, WHO developed a slightly simplified version of the approach used in the USA and tested it in some African hospitals. The protocol is based on the widely accepted US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC/NHSN) definitions for SSI.1 However, some settings may not have access to hiqh-quality microbiology laboratories, so they may need to rely primarily on clinical signs and symptoms to identify SSI. The focus of this approach is to promote collection of data on process measures, because improvement in these practices are known to affect SSI rates.

Recognizing that surveillance is challenging and demanding, especially when human resources and time are limited, WHO developed a slightly simplified version of the approach used in the USA and tested it in some African hospitals. The protocol is based on the widely accepted US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention–National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC/NHSN) definitions for SSI.1 However, some settings may not have access to hiqh-quality microbiology laboratories, so they may need to rely primarily on clinical signs and symptoms to identify SSI. The focus of this approach is to promote collection of data on process measures, because improvement in these practices are known to affect SSI rates.

For feasibility reasons, the WHO approach is based on in-hospital and post-discharge surveillance of up to 30 days only. Patient follow-up between discharge to 30 days includes phone calls and involvement of the patient in recognizing signs and symptoms of SSI.

-

SSI and the WHO Core Components (5 min)

The WHO core components of IPC programmes are a key resource for IPC leaders, and a roadmap for effective implementation and improvement of IPC (see the Core Components and Multimodal Strategies module). These evidence-based guidelines have eight recommendations, some of which are specifically related to SSI, while they are all priority if IPC programmes are to be successful in support of SSI prevention. As with any map, they require some interpretation. The IPC focal person should develop, coordinate, and oversee improvement plans to reduce SSI alongside the valuable information contained in the core components guideline.

Click or tap each of these selected core components. They were informed by SSI prevention studies and are particularly relevant for SSI prevention.

Core component 2

This recommendation highlights the overall importance of IPC guidelines, education, and monitoring, all of which apply to SSI prevention. It also highlights the importance of conducting training for health care workers when introducing new or updated guidelines, and emphasizes the importance of monitoring actual adherence to guidelines through implementation in the field. You can use this WHO statement to help sell the importance of SSI prevention to staff, administrators, and decision-makers.

Core Component 2: National and facility level infection prevention and control guidelines Recommendation The panel recommends that evidence-based guidelines should be develeoped and implemented for the purpose of reducing HAI and AMR. The education and training of relevant health care workers on the guideline recommendations should be undertaken to achieve successful implementation.

(Strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Core component 4

Conducting SSI surveillance has been shown to contribute to substantial reduction in SSI rates. Early detection of infection can help control clusters and outbreaks. Surveillance systems at both health facility and national levels need support from senior staff and require resources if they are to be effective.

Core Component 4: Health care-associated infected surveillance 4a. Health care facility level

Recommendation The panel recommends that facility-based HAI surveillance should be performed to guide IPC interventions and detect outbreaks, including AMR surveillance with timely feedback of results to health care workers and stakeholders and through national networks.

(Strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Core Component 4: Health care-associated infected surveillance 4b. National level

Recommendation The panel recommendations that national HAI surveillance programmes and networks that include mechanisms for timely data feedback with the potential to be used for benchmarking purposes should be established to reduce HAI and AMR.

(Strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Core component 5

Multimodal strategies are recommended as the most effective way to implement IPC guidelines and best practices; therefore, they are a core component of IPC. SSI prevention studies contributed to informing the development of these evidence-based recommendations. We will go into more detail about multimodal strategies for SSI prevention in the third section of this module.

Core Component 5: Multimodal strategies for implementing infection prevention and control activities 5a. Health care facility level

Recommendation The panel recommends that IPC activities using multimodal strategies should be implemented to improve practices and reduce HAI and AMR.

(Strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Core Component 5: Multimodal strategies for implementing infection prevention and control activities 5b. National level

Recommendation The panel recommends that national IPC programmes should coordinate and facilitate the implementation of IPC activities through multimodal strategies on a nationwide or sub-national level.

(Strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Core component 6

Regular monitoring/audits of health care practices according to current standards should be performed to prevent and control all HAI and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) at the facility level, with timely feedback provided. This links clearly to SSI activities at both national and facility levels. The importance of monitoring process indicators/practices that influence SSI outcome, such as surgical hand preparation, patient preparation, surgical antibiotic prophylaxis, is known to influence behaviour and improvement over the long term.

Core Component 6: Monitoring/audit of IPC practices and feedback and control activities 6a. Health care facility level

Recommendation The panel recommendations that regular monitoring/audit and timely feedback of health care practices according to IPC standards should be performed to prevent and control HAI and AMR at the health care facility level. Feedback should be provided to all audited persons and relevant staff.

(Strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

Core Component 6: Monitoring/audit of IPC practices and feedback and control activities 6b. National level

Recommendation The panel recommends that a national IPC monitoring and evaluation programme should be established to assess the extent to which standards are being met and activities are being performed according to the programme's goals and objectives. Hand hygiene monitoring with feedback should be considered as a key performance indicator at a national level.

(Strong recommendation, very low quality of evidence)

See the WHO Core Components and Multimodal Strategies module to review these guidelines. See the Resources section for a list of the core components and multimodal strategies.

See the WHO Core Components and Multimodal Strategies module to review these guidelines.

-

Summary (5 min)

In this section, you learned that preventing SSI is a crucial part of an IPC programme. Conducting SSI surveillance and understanding the data are important in understanding and explaining not only the frequency and magnitude of this problem locally, but also why prevention is important. Using reliable, standardized methods, you may be able to compare your facility’s SSI rates to global SSI rates and use global, regional, and local figures to support your case for implementing prevention measures. You can also use your facility data to prioritize the prevention activities that are likely to have the greatest impact in your facility over time.

-

References

- CDC/NHSN surveillance definitions for specific types of infections. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2018. https://www.cdc.gov/nhsn/pdfs/pscmanual/9pscssicurrent.pdf

- The burden of endemic health care-associated infection worldwide. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. ( http://www.who.int/infection-prevention/publications/burden_hcai/en/)

- Allegranzi B, Bagheri Nejad S, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011 Jan 15;377(9761):228-41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61458-4. Epub 2010 Dec 9.

- Bagheri Nejad S, Allegranzi B, Syed SB, Ellis B, PIttlet D. Health care-associated infection in Africa: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011 Oct 1;89(10):757-765. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.088179. Epub 2011 Jul 20.

- Updated systematic review – WHO unpublished data, 2017.

- Biccard BM, Madiba TE, Kluyts HL, Muniemvo DM, Madzimbamuto FD, Basenero A, et al. Perioperative patient outcomes in the African Surgical Outcomes Study: a 7-day prospective observational cohort study. Lancet. 2018 Apr 21; 391(10130):1589-1598. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30001-1. Epub 2018 Jan 3.

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Annual epidemiological report 2016 – surgical site infections. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. (https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/surgical-site-infections-annual-epidemiological-report-2016-2014-data.).

- National and state healthcare-associated infections progress report. Atlanta (GA): National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016. (http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/progressreport/hai-progress-report.pdf, accessed 10 Aug 2016).

- Sievert DM, Ricks P, Edwards JR, Schneider A, Patel J, Srinivasan A et al. Antimicrobial-resistant pathogens associated with healthcare-associated infections: summary of data reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2009–2010. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013 Jan;34(1):1–14. doi: 10.1086/668770. Epub 2012 Nov 27.