Health-Care Associated Infection (HAI) Surveillance Part 1

Hundreds of millions of patients around the world are affected by health care-associated infections (HAI). Every day, HAI results in prolonged hospital stays, long-term disability, increased resistance of microorganisms to antimicrobials, massive additional costs for health systems, emotional and personal burden for patients and their family, and unnecessary deaths. To prevent HAI, it is important to identify their causes, understand how big the problem is, and evaluate whether interventions to reduce HAI are successful.

This first module on HAI surveillance will cover basic definitions, the epidemiology of HAI, and the steps for conducting surveillance.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this module, you will be able to:

- explain basic concepts of epidemiology and their application to HAI surveillance;

- describe how to plan the initial steps for HAI surveillance;

- describe how to assess surveillance of a target population;

- describe how to select surveillance outcomes; and

- identify and use standardized HAI case definitions.

Learning Activities Estimated time:

-

Newsha’s Story Part 1 (5 min)

For the last few years, Newsha has been working as a nurse in the 150-bed general hospital of her home town. She has also had training in infection prevention and control (IPC) and is aware that preventing HAI can save many lives. As part of an IPC national programme, the district has decided that all health care facilities will appoint an IPC focal point.

The facility director decided to appoint Newsha to the IPC committee. When the director asked her what her priorities would be, Newsha proudly said, “I’ll immediately start developing a plan to assess and improve hand hygiene.” However, during a break with her friend and fellow nurse Nelya, Newsha becomes aware of a pre-term baby who died of an infection that same morning. “His name was Nima and he was the cutest baby ever!” said Nelya. “It’s so sad, poor parents… And it was a while since we had such a bad infection. Another little one, Puya, is starting to run a fever, let’s hope he’ll be ok.”

That’s when it struck Newsha: she should start recording all these events and determine where the babies got the infection! Maybe it could stop the transmission; she remembered the surveillance module she took during an IPC training. Surveillance of HAI was key to identify the chain of transmission and was clearly considered a core component of IPC.

She went back to her office and started designing her next steps: she needed to convene a multidisciplinary team, including doctors, pharmacists, and microbiologists. Together they would decide what kind of surveillance they would set up: active or passive? Which population would they target? What information would they seek and collect, and with which tools? Which case definitions would they use?

Keep this story in mind as you learn about basic definitions of HAI and the steps for conducting surveillance.

-

What Is HAI Surveillance? (5 min)

Let us start by looking at a few definitions.

HAI are infections people get during the process of receiving care in a hospital or other health care facility. HAI are not present or incubating at the time of a patient’s admission to a health care setting.

Surveillance is the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, interpretation and evaluation of data closely integrated with the timely dissemination of these data to those who need it. Conducting high quality surveillance is crucial to identify how big a problem is and to assess the impact of any prevention or improvement intervention.

Hospital surveillance is the ongoing, systematic collection, analysis, interpretation and dissemination of health data (e.g., HAI) to help guide clinical and public health decision-making and action (i.e., information for action).

The purpose of HAI surveillance is to provide data on HAI occurrence for decision-making, policy and research. It helps describe microbiological profiles of pathogens causing HAI, and, depending on most frequent infections, it provides critical information to plan and tailor IPC interventions. You can use surveillance to detect changes in HAI rates over time and evaluate the impact of HAI prevention and control measures. Finally, surveillance can help detect outbreaks. With appropriate methodologies, surveillance data can be used for benchmarking and as an indicator of quality of care and patient safety.

Benchmarking is the process of comparing oneself to others that are performing similar activities for purposes of improving performance.In summary, conducting surveillance allows you to:

- provide baseline endemic infection rates

- identify increases in infection rates (i.e., clusters or outbreaks)

- provide information on the occurrence of HAI (incidence or prevalence)

- evaluate efficacy of control measures

- reinforce appropriate infection prevention and patient care practices

- Provide data for insurance and legal purposes

- provide data for comparisons

- engage in problem solving and/or research, and planning

- measure the impact of implementing recommendations

- enhance a health care organization’s performance

- reduce the risk of adverse outcomes.

The WHO Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level outline specific evidence-based recommendations on HAI surveillance.1 Tap or click the tabs below to learn more about these specific recommendations at each level.

Core component 4: HAI surveillance

4a. Health care facility level

Recommendation

The panel recommends that facility-based HAI surveillance should be performed to guide IPC interventions and detect outbreaks, including antimicrobial resistance (AMR) surveillance with timely feedback of results to health care workers (HCWs) and stakeholders and through national networks.Core component 4: HAI surveillance

4b. National level

Recommendation

The panel recommends that national HAI surveillance programmes and networks that include mechanisms for timely data feedback and with the potential to be used for benchmarking purposes should be established to reduce HAI and AMR.For more information, take the Core Components and Multimodal Strategies module.

-

Epidemiology of HAI (5 min)

Epidemiology is the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related events in specified populations, and the application of this knowledge to control relevant health problems.

Hospital epidemiology is a practical subdiscipline that is an essential function in the health care system (although often underrecognized and under supported). Hospitals are complex institutions where patients go for prevention, diagnosis or treatment. However, hospitals are also places where patients may encounter risks to their health. Hospital epidemiology focuses on identifying, understanding and minimizing or eliminating these risks to prevent and control HAI. In other words, hospital epidemiology is the application of epidemiological methodologies to the hospital setting.

HAI are one of the most common adverse events in health care. They affect both high-income and resource-limited countries due to the rapid increase in people using health services and to the increase in use of highly technological and invasive procedures in modern health care.

Studying the epidemiology of HAI through the use of HAI surveillance data can help us understand how big and widespread the problem is, the likely causes, the risk factors (e.g., patient type, unit of treatment) and the transmission cycle. Knowing all these pieces of information can help determine which prevention strategies might work best.

-

Who Is Responsible for Surveillance? (5 min)

Ideally, a motivated, multidisciplinary IPC team will be responsible for data collection, analysis, interpretation and dissemination of findings. Size and composition of the team will depend on availability and interest of local staff, but it is preferable that the team consist of an IPC/hospital epidemiology physician, a microbiologist and a nurse lead with clinical experience. This team will need protected time for surveillance responsibilities and training in hospital epidemiology/surveillance methods and regular supervision by the national IPC team to ensure that the data collected is of good quality.

If no dedicated hospital IPC team is available, surveillance can be done by:

- nursing personnel dedicated to IPC;

- IPC link nurses or practitioners of other disciplines as relevant (e.g., surgeons, pharmacists);

- those in other existing surveillance systems; and

- epidemiology/biostatistics support staff (e.g., initial training, ongoing supervision visits from national level).

HAI surveillance can be particularly challenging in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) because of a lack of dedicated human resources, funds and expertise in epidemiology and IPC. In LMICs, it may be difficult to apply standard definitions due to:

- limited expertise and/or skills for data interpretation and use

- lack of reliable microbiological and other diagnostic tools

- poor quality information from patient records.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Steps for Planning a Surveillance System (5 min)

When planning for HAI surveillance, it is helpful to create a written surveillance plan that includes the items listed below.

- Rationale for surveillance population and targets

- Purpose, objectives, use of data

- Responsible surveillance team

- Methodology: case definitions, numerator and denominator data sources, type of data collection

- Evaluation of data quality

- Reporting and feedback post implementation evaluation

In some instances, surveillance data may already have been collected as part of other surveillance programmes or ongoing quality improvement activities. Before beginning to collect data, find out whether the data is already being collected or if a similar surveillance system is already in place.

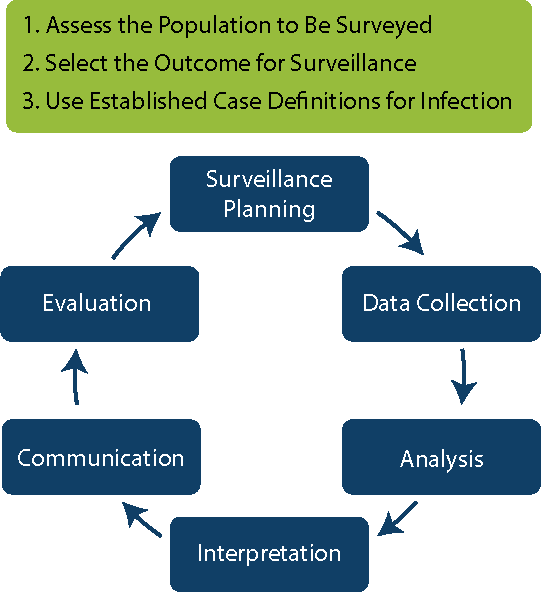

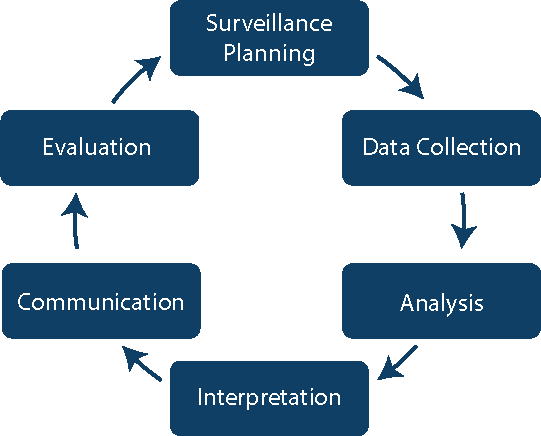

The rest of the Surveillance modules will discuss the steps for conducting surveillance at your facilities or as part of a national programme. Click or tap on each phase to see the steps associated with it.

Surveillance Planning

- Assess the Population to Be Surveyed

- Select the Outcomes for Surveillance

- Use Established Case Definitions

Data Collection

- Collect the Surveillance Data

Analysis

- Calculate and Analyse Surveillance Rates

- Apply Risk Stratification Methodology

Interpretation

- Interpret Infection Rates

Communication

- Communicate and Use Surveillance Information to Improve Practice

Evaluation

- Evaluate the Surveillance System

-

Step 1: Assess the Population to Be Surveyed (5 min)

As part of the planning phase, determine the target population that will be included in the surveillance system. Including more subjects in surveillance can give more reliable results, but it is also more resource intensive to collect and analyse that data. Decisions on which population to target should be made according to the local context, i.e., a particular group of patients (such as paediatric patients) or time period.

The following questions can help you design your surveillance programme.

- What types of patients receive care or are at greatest risk of infection in the facility?

- What type of care is being provided (e.g., Intensive care, surgery, chronic diseases, old/young)?

- What are the most common diagnoses (e.g., burns, coronary insufficiency)?

- Which invasive procedures are most frequently performed?

- Are invasive devices commonly used/inserted (e.g., insertion of indwelling urinary catheters or vascular catheters (both peripheral and central line), use of ventilators)?

- What surveillance outcomes should be targeted?

-

Step 2: Select Outcomes (5 min)

Next, prioritize which outcomes to measure in your target surveillance population. Click or tap on the tabs to learn more about each category of surveillance indicators.

Structure and process indicators

Structure and process indicators track enablers and key steps that result in changes in outcome. To collect information on IPC structure indicators, you could look at whether there are isolation rooms or the amount of alcohol-based handrub (ABHR) used. For process indicators, you might look at the actions of HCWs to improve quality or compliance (e.g., hand hygiene compliance). Other examples of process indicators include:

- adherence to central line insertion practices;

- observation of proper surgical care processes (such as performing preoperative antimicrobial prophylaxis);

- adherence to safe injection practices;

- personal protective equipment compliance; and

- personnel compliance with protocols.

Monitoring structure and process indicators is a different activity than HAI surveillance (which detects outcome indicators) but it is a key activity/core component of IPC programmes. It represents a useful complement to HAI surveillance, particularly when appropriate indicators are selected for specific types of HAI (e.g., ABHR or antimicrobial soap availability in the operating theatre, or time of administration of surgical antibiotic prophylaxis to complement surgical site infection [SSI] surveillance).

Outcome indicators

Outcome indicators are the endpoint or the result of care or performance. Examples include tracking:

- various types of infections, such as bloodstream infections (BSI), urinary tract infections (UTI), pneumonia, SSI, central line-association bloodstream infections (CLABSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) and ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP);

- infections or colonization by a specific organism, such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), vancomycin-resistant enterococci (VRE), other multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs) and influenza;

- patient mortality; and

- hospital length of stay.

Data Used for Prioritization of HAI Surveillance in a Fictional Hospital

Type of Infection % of all HAIs % Extra Days Hospitalized Due to Infection % Extra Costs Due to Infection % of Preventable Infections SSI 24 57 42 35 Pneumonia 10 11 39 22 UTI 42 4 13 33 Bacteraemia 5 4 3 32 You can use a similar table to track these and other criteria (e.g., disability adjusted life years, quality adjusted life years, deaths, transmissibility) when prioritizing which infections to include in your surveillance efforts.

Selecting Targets

Good indicators are those which are based on consideration of:

- high incidence or prevalence (e.g., particular pathogens, populations, related procedures);

- severity, disability or mortality;

- preventability and ability to control/treat;

- new clinical services;

- accessibility of data and resources; and

- suitable benchmark (i.e., data that can be used to compare progress over time or to other hospitals, such as the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium).

-

Step 3: Use Established Case Definitions (15 min)

We will now move on to the third part of surveillance planning: HAI case definitions. A surveillance case definition is a set of uniform criteria used to define a disease that enables HCWs to classify and count cases consistently for surveillance purposes. Always use standardized case definitions so that the data you collect can be compared to data collected in future surveillance activities or compared to other facilities.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Healthcare Safety Network (CDC NHSN) and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) both have commonly used, standardized HAI case definitions for which they have established validity and reliability. Two important definitions to make clear are:

- Hospital-acquired infection (HAI): According to CDC NHSN, the case definition of HAI is that the date of infection (event) occurs on or after the third calendar day of admission to an inpatient location where day of admission is calendar day 1.

- Present on admission: Date of event of site-specific infection criterion occurs on day of admission to an inpatient location (calendar day 1), the 2 days before admission, and the calendar day after admission (present on admission time period).

Ideally, international, standardized HAI case definitions should be used to ensure reliability and consistency with other surveillance programmes. However, these standardized case definitions can be complex and difficult to apply, particularly in low-resource settings. Starting with surveillance of process and structure indicators can be a valid initial approach until there is sufficient infrastructure and resources for HAI surveillance. If low-resource settings wish to adapt international HAI case definitions, it is critical to ensure:

- that established experts in surveillance or IPC/HAI can help guide adaptation (e.g., could consult regional surveillance expertise);

- that adapted case definitions are validated; and

- understanding that benchmarking or comparison with other countries will be challenging.

Click or tap on each tab to learn about the CDC and ECDC case definitions for an HAI.

CDC NHSN case definitions

CDC NHSN case definitions are commonly used as international case definitions. While, NHSN definitions are designed for use in the context of the health care system of the United States of America (USA), some international settings also use them. The case definitions are based on:

- clinical signs/symptoms

- laboratory investigations

- radiological investigations.

These case definitions might be difficult to implement in LMICs because of the need for technical expertise, laboratories and other diagnostic enablers.

CDC NHSN defines HAI as infections occurring on or after the third calendar day of admission where day of admission is calendar day 1 (in the infection window period).

ECDC case definitions

Onset of HAIDay 3 onwards Day 1 (day of admission) or day 2: SSI criteria met at any time after admission (including previous surgery 30 days / 90 days Day 1 or day 2 and patient discharged from acute care hospital in preceding 48 hours Day 1 or day 2 and patient discharged from acute care hospital in preceding 28 days if Clostridium difficile infection present Day 1 or day 2 and patient has relevant device inserted on this admission prior to onset Day 1 or day 2 after birth for neonates Meets the case definition on the day of survey Patient is receiving treatment and HAI has previously met the case definition between day 1 of treatment and survey dayNow let us see how the case definitions can be applied to various types of HAI. Click or tap on each tab to learn more.

Pneumonia

When planning your surveillance efforts, take the following factors into consideration:2

- HAI pneumonia is often found in patients on ventilators in ICUs (i.e., VAP);

- mortality is high but difficult to determine because patient comorbidity is also high;

- microorganisms colonize the stomach, upper airway and bronchi, or contaminate respiratory equipment;

- the case definition depends on clinical and radiologic criteria;

- the diagnosis is more specific when quantitative microbiological samples are obtained; and

- risk factors include type and duration of ventilation, quality of respiratory care, and severity of the patient’s condition.

Consider the following criteria when defining a case of hospital-acquired pneumonia:2

- a physician’s diagnosis of pneumonia alone is not an acceptable criterion for health care-associated pneumonia;

- it is important to distinguish between changes in clinical status due to other conditions, such as myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, respiratory distress syndrome;

- early onset pneumonia occurs during the first four days of hospitalization and is often caused by strains of Moraxella catarrhalis, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae; and

- late onset pneumonia emerges after four days of hospitalization and is more likely caused by Gram-negative bacilli or S. aureus.

The CDC NHSN definition requires clinical, radiological and laboratory criteria.

The ECDC definition differs from CDC NHSN’s in that it is mandatory to fill in the microbiology information but includes the possibility that no test was done. This provides information on testing frequency.

CDC NHSN definitionAt least one of the general clinical criterion (can be different for children and infants)- Fever >38°C

- Leucopenia (<4,000 WBC/mm3) or leucocytosis (≥12,000 WBC/mm3)

- Altered mental status ≥ 70 year

- New onset of purulent sputum, or change in character of sputum, or increased respiratory secretions, or increase suctioning requirements

- Cough, dyspnoea or tachypnea

- Rales or bronchial breathing sounds

- Worsening gas exchange

Patient with underlying diseases (pulmonary or cardiac) has two or more chest X-rays patient without underlying diseases has one or more chest X-ray, withOne microbiologic criterion (optional—not necessary for confirmation of HAI)- new or progressive and persistent infiltrates or

- consolidation or

- cavitation

- Positive quantitative cultures of lower respiratory tract specimen (e.g., bronchoalveolar lavage or protected specimen brushing)

- Positive blood culture not related to other source of infections

- Positive pleural fluid culture

- Positive histopathologic exam

Another difference between the two case definitions involves removal of the ventilator. Both definitions say that the patient must have been on mechanical ventilation for more than 2 calendar days on the date of the event (with the day of ventilator placement being day 1) and that the ventilator must have been in place on the date of the event or the day before. However, ECDC’s case definition allows for the ventilator to have been removed within the past 48 hours.

UTI

When planning your surveillance efforts, take the following factors into consideration:

- UTI are a very common type of HAI.

- They cause less morbidity than other HAI but can occasionally lead to bacteraemia and death.

- The diagnosis is based on clinical and laboratory criteria.

- Bacteria arise from the gut flora, either normal (Escherichia coli) or hospital acquired.

- It is important to distinguish between asymptomatic and symptomatic UTI. Asymptomatic UTI do not require antibiotic treatment and are currently excluded from the surveillance of HAI. BSI secondary to asymptomatic bacteriuria are reported as BSI with source (origin).

The CDC NHSN and ECDC case definition for catheter associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is that a patient with a UTI has an indwelling urinary catheter in place for >2 calendar days on the date of event and an indwelling urinary catheter was in place on the date of the event or the day before. The CDC NHSN definition stipulates that if an indwelling urinary catheter was in place for >2 calendar days and then removed, the date of event for the UTI must be the day of discontinuation or the next day for the UTI to be catheter-associated. The ECDC definition says that the catheter must have been in place within 7 days before positive laboratory results or symptoms.

UTI-A

Microbiologically confirmed symptomatic UTIMore than 1 of the following criteria (no other cause)- Fever >38°C

- Urgency

- Frequency

- Dysuria

- Suprapubic tenderness

UTI-B ECDC case definition only

Microbiologically unconfirmed symptomatic UTI2 of the following criteria (no other cause)- Fever >38°C

- Urgency

- Frequency

- Suprapubic tenderness

- Positive dipstick urine

- Pyuria (≥ 10 white blood cells/mL)

- Organisms/gram of unspun urine

- ≥2 urine cultures same uropathogen ≥102 organisms/mL

- Physician diagnosis of UTI

- Physician appropriate treatment for UTI

Do not report UTI-C asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Note on CAUTI: The CDC/NHSN case definition requires that the urinary catheter be present in situ within 2 days of the onset of signs and symptoms. The ECDC case definition requires the urinary catheter to be in place within 7 days.

The CDC NHSN definition does not include a purely clinical option — microbiological confirmation is always needed. These differences in CAUTI definitions make it difficult to compare health care-acquired UTI epidemiology between Europe and the USA. This should be considered when approaching your choice for which definition you use as it will have an impact on how you benchmark your rates.

For more information on preventing UTI, take the Catheter-Associated Urinary Tract Infections module.

BSI

There are two types of BSI. Primary BSI is not related to an infection at another body site. Secondary BSI is related to an infection at another body site (e.g., pneumonia, UTI or SSI).

When planning your surveillance efforts, take the following factors into consideration:

- BSI are a major cause of morbidity and mortality.

- They occur at the entry site of an IV device or in the subcutaneous path of the catheter (tunnel infection).

- Resident or transient cutaneous flora is the source of infection.

- Organisms colonizing the IV catheter may produce bacteraemia without visible external infections.

- Insertion of central lines can cause CLABSI.

- The main risk factors are length of catheterization, level of asepsis at insertion and catheter care.

BSI are classified according to clinical and laboratory criteria as laboratory-confirmed BSI and clinical sepsis.BSI must have a recognized pathogen cultured from 1 or more blood cultures patient has at least 1 of the following signs or symptoms: fever, chills or hypotension and for patients ≤1 year fever, hypothermia, apnoea or bradycardia common skin contaminant is cultured from 2 or more blood cultures drawn on separate occasions.The table below lists recognized pathogens vs. common skin contaminants. Once you have identified an infection, knowing the microorganism causing the infection will help you understand how the patient got infected. For example, if you find a diphtheroid (normally colonizing the skin), the infection probably happened during the insertion of a device in the skin (e.g., an injection) and this could be classified as a primary BSI.

Recognized Pathogens Common Skin Contaminants Enterococcus spp. Coagulase Negative Staphylococci (CONS) E. coli Diphtheroids Pseudomonas spp. Bacillus Acinetobacter spp. Others Candida spp. Others LMICs can use a different case definition for unidentified severe infections (formerly clinical sepsis) if there is no access to a microbiology laboratory. Cases must meet the following criteria:

- Patient has at least 1 of the following clinical signs or symptoms with no other recognized cause: fever, hypotension or oliguria, and, for infants ≤1 year old, fever, hypothermia, apnoea or bradycardia.

- Blood culture was not done or was negative.

- There is no apparent infection at another site.

- The physician begins treatment for sepsis.

For more information on preventing BSI, take the Bloodstream Infections module.

SSI

The case definitions vary according to the level of incision/infection. Unlike other HAI, the date of the event is not the date of admission to hospital, but the date of the surgical procedure.

Superficial incisional SSIDate of event for infection occurs within 30 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) involves only the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the incision patient has at least one of the following- Purulent drainage from the superficial incision.

- Organisms identified from an aseptically-obtained specimen from the superficial incision or subcutaneous tissue by a culture or non-culture-based microbiologic testing method which is performed for the purpose of clinical diagnosis or treatment.

- Superficial incision that is deliberately opened by a surgeon, attending physician, or other designee and culture or non-culture based testing is not performed patient has at least one of the following signs or symptoms: pain or tenderness, localized swelling, erythema, or heat.

- Diagnosis of a superficial incisional SSI by the surgeon, attending physician, or other designee.

Deep incisional SSIThe date of event for infection occurs within 30 or 90 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) according to Surveillance Periods for SSI Following Selected NHSN Operative Procedure Categories involves deep soft tissues of the incision (for example, fascial and muscle layers) patient has at least one of the following- Purulent drainage from the deep incision.

- A deep incision that spontaneously dehisces; or is deliberately opened or aspirated by a surgeon, attending physician, or other designee; the organism is identified by a culture or non-culture based microbiologic testing method which is performed for purposes of clinical diagnosis or treatment or culture or non-culture based microbiologic testing method is not performed; patient has at least one of the following symptoms: fever (< 38º C); localized pain or tenderness. A culture or non-culture based test that has a negative finding does not meet this criterion.

- An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the deep incision that is detected on gross anatomical or histopathologic exam or imaging test.

- The ECDC case definition adds a fourth criteria: Diagnosis of deep incisional SSI made by a surgeon or attending physician.

Organ/space SSIDate of event for infection occurs within 30 or 90 days after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) according to Specific Sites of an Organ/Space SSI infection involves any part of the body deeper than the fascial/muscle layers that is opened or manipulated during the operative procedure patient has at least one of the following- Purulent drainage from a drain that is placed into the organ/space (for example, closed suction drainage system, open drain, T-tube drain, CT guided drainage).

- Organisms are identified from fluid or tissue in the organ/space by a culture or non-culture based microbiologic testing method which is performed for purposes of clinical diagnosis or treatment.

- An abscess or other evidence of infection involving the organ/space that is detected on gross anatomical or histopathologic exam, or imaging test evidence suggestive of infection.

- The ECDC case definition adds a fourth criteria: Diagnosis of deep incisional SSI made by a surgeon or attending physician.

Because 13—71% of SSI cases are diagnosed post-discharge, a proper surveillance programme needs to follow up for 30 or 90 days (depending on the type of surgery). This can be challenging in LMICs, in part because patients may be unwilling or unable to return to the same hospital for follow-up visits. However, it is crucial to follow up with patients post surgery since missed cases can result in underestimation of the true risk of SSI. To increase detection of SSI post surgery:

- Send out discharge questionnaires.

- Track outpatient clinic visits.

- Track outpatient clinic visits.

- Purchase a dedicated SSI surveillance phone that has its own monthly contract with an itemized billing list to compare to the call logs.

- Have staff practice answering calls from “dummy patients” to ensure that they are checking identities, identifying unexpected situations and maintaining patient confidentiality.

- Collect data via readmission records.

For more information on preventing SSI, take the Surgical Site Infections module.

There are case definitions for other HAI that occur less frequently. These are

- bone and joint infection

- central nervous system infection

- cardiovascular system infection

- eye, ear, nose, throat or mouth infection

- LRTI other than pneumonia

- gastrointestinal system infection

- reproductive tract infection

- skin and soft tissue infection

- systemic infection

- urinary system infection.

The ECDC case definition does not include this criterion.The ECDC case definition does not include this criterion.The ECDC case definition does not include this criterion.The ECDC case definition does not include this criterion.The ECDC case definition also includes ronchi and wheezing.The ECDC case definition also includes CT scan.The ECDC case definition does not include this criterion.In the ECDC case definition, this is not optional. In addition to the criteria listed, other criteria include- positive sputum culture or non-quantitative culture

- no positive microbiology.

The modern definition of sepsis includes organ dysfunction. Hence, cases of BSI without laboratory confirmation are now called “unidentified severe infection”.In the ECDC case definition, this is with or without laboratory confirmation.The ECDC case definition also requires that the infection appears to be related to the operation.The ECDC case definition has a different requirement: Purulent drainage from the deep incision but not from the organ/space component of the surgical site.previously closed wound reopeningThis requirement is not part of the ECDC case definition.According to the ECDC case definition, the criteria is

The date of event for infection occurs within 30 days (if no implant is in place) or 90 days (if implant is in place) after the surgical procedure (where day 1 = the procedure date) and infections seem to be related to the operation. -

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Summary (5 min)

In this module, you learnt about what HAI surveillance is, how the HAI surveillance team should be composed and the first step in conducting HAI surveillance: planning. When planning your HAI surveillance programme, identify the target population by thinking about who is at high risk for infection and who will be undergoing which kind of procedures.

As part of the planning phase, you should also prioritize which outcomes to measure in your target surveillance population. Structure indicators measure what resources exist in the hospital, e.g., isolation rooms. Process indicators measure HCW practices, such as regular and consistent performance of hand hygiene. Outcome indicators are the endpoint or the result of care or performance, including various types of infections.

The final activity in the planning phase is to determine which case definitions to use. You learnt about internationally used case definitions for several types of infections. Remember to make sure to use standardized case definitions so that the data you collect can be compared to data collected in future surveillance activities or compared with data from other facilities.

-

References

- World Health Organization. Guidelines on Core Components of Infection Prevention and Control Programmes at the National and Acute Health Care Facility Level. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016 (accessed 30 November 2019).

- Pan American Health Organization. Epidemiological Surveillance of Healthcare-Associated Infections. Washington (DC): Pan American Health Organization; 2011 (accessed 30 November 2019).