Session 1: HIV Prevention

Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs)

In this session, we will discuss the importance of practicing preventive health behaviors, the universal standard precautions to prevent occupational exposure to bloodborne pathogens, including HIV and how to treat exposure with post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).

In this section, you will learn about STI transmission and the factors that increase risk of getting STIs. This section will also cover how to take a client’s history and examine them for an STI. Finally you will learn about the management of several STIs and their symptoms.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- Describe STI transmission and factors that increase risk.

- Outline management of major STI syndromes.

- Summarise how to take history and examine clients with an STI.

- Explain common symptoms of STIs.

Learning Activities

-

Introduction (5 min)

In this session, we have discussed prevention and control strategies of HIV and other infections in the workplace, how to treat exposure with post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), and how male circumcision can prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. Now let’s take a closer look at the sexually transmitted infections that can increase the risk of HIV transmission, their common symptoms, and how to take history and examine clients with an STI.

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) have been known since ancient times and they remain a major public health problem. The most important STIs and infectious agents are listed below.

Sexually transmitted infection Infectious agent - HIV

- Hepatitis B

- Syphilis

- Gonorrhoea

- Chlamydia infections

- Trichomoniasis chancroid

- Genital herpes genital warts

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- Hepatitis B virus

- Treponema pallidum

- Neisseria gonorrhoeae

- Chlamydia trachomatis

- Trichomonas vaginalis

- Haemophilus ducreyi

- Herpes simplex virus

- Human papillomavirus

Relationship Between HIV and STIs

The interaction of HIV and conventional STIs is bi-directional; meaning, HIV can change the clinical presentation and treatment outcomes of other STIs. At the same time, conventional STIs can increase vulnerability to HIV infection by causing ulcers or an inflammatory response that affords easy entry by HIV.

STIs and HIV commonly share the same major transmission routes, and interventions to prevent these classical STIs also decrease HIV incidence. Moreover, similar behavioural risk factors operate in both situations where the youth, mobile populations and individuals who frequently change sexual partners are commonly affected. Clinical manifestations of STIs can present differently in persons infected with HIV and the treatment may be affected when infection with HIV co-exists, which we will discuss later in this section.

-

Transmission and Factors that Increase Risk (5 min)

Transmission of STIs

STIs are transmitted during unprotected vaginal, anal, or oral sexual intercourse. Some of the infectious agents, such as HIV, hepatitis B, and syphilis, can be passed vertically from an infected mother to her unborn baby, and can be transmitted via blood transfusions. Many people who have an infection experience no symptoms. Others may not experience symptoms for several weeks. The most common STI symptoms include genital ulcers, pelvic inflammatory disease, urethral discharge, and vaginal discharge. If left untreated, some STIs can have serious consequences and may cause acute and chronic illness, infertility, long term disability, and even death.

Factors That Increase Risk of Transmission

Unprotected, penetrative sexual intercourse is a risk factor for acquiring or transmitting STIs, but not all acts of unprotected sex result in acquiring or transmission the infection. Whether or not a person will be infected depends on many factors, both biological and behavioural. Tap on the tabs below to learn about each of the factors that increase the risk of STI transmission.

Biological Factors

The age of the person, gender, and immune status have influence on the transmission of STIs.

Age: The vaginal mucosa and cervical epithelium in pre-adolescent girls are of a nature that makes the individuals more vulnerable to STIs than older women. The epithelium is columnar in these girls. Pathogens, such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae (N. gonorrhoeae) can easily invade such cells. As the individuals grow older, the lining of the vagina becomes squamous and more resistant to attack by such pathogens. It is important to note that in societies where girls marry or become sexually active during early adolescence, they are especially at higher risk of infection than their more mature women.

Gender: The larger the surface area of attack the more likely that infection will invade. Since the mucosal surface lining the vagina is relative larger that the urethra in men, the chances of acquiring infection are much greater in women than in men.

Immune status: The immune status of the host and virulence of the infective agent affect transmission of STIs. For example, persons whose immunity is affected by HIV infection are more vulnerable to infection with other STIs than the non-HIV-infected persons. At the same time, certain STIs, particularly those that cause genital ulcerations, increase the risk of transmission and acquisition of HIV—itself a sexually transmitted infection.

Behavioural Factors

Some sexual behavioural factors may increase the chances of acquiring an STI. Such behaviours are known as “risky sexual behaviours”. Risky sexual behaviours include the following:

- Changing sexual partners frequently.

- Having more than one sexual partner at the same time (concurrent sexual partnerships).

- Having sex with “casual” partners, such as sex workers or clients of sex workers.

- Being a sex worker or being a client of sex workers.

Other behaviours associated with risk of infection include:

- Men who have sex with men tend to have multiple sexual partners or frequently change partners, making this a high-risk sexual behaviour.

- Skin-piercing, including the use of unsterile needles to give injections or tattoos, scarification or body piercing, and circumcision using shared knives.

- Use of alcohol or other drugs before or during sex: alcohol or drug use may negatively affect cautious preventive practices, such as condom use, alcohol may diminish the perception of risk, resulting in not using a condom; or, if a condom is used, it may not be used correctly.

- A sexual partner who has one or more sexual partners or who engages in other high-risk behaviours will be more exposed to STIs and, in turn, is more likely to transmit an STI.

Social Factors

A number of social factors link both gender and behavioural issues and may affect a person’s risk or vulnerability to acquiring an STI.

- In most cultures, women have very little power over sexual practices and choices, such as use of condoms.

- Women tend to be economically more dependent on their male partners and are, therefore, more likely to tolerate men’s risky sexual behaviours, thus putting themselves at risk of infections.

- Sexual violence tends to be directed more towards women by men, making it difficult for women to discuss STIs with their male counterparts.

- In some societies the girl-child tends to be married off to an adult male at a very young age, thus exposing the girl to infections while she is biologically more vulnerable.

- Men or women whose jobs separate them from their regular sexual partners for long periods of time, such as military personnel, long-distance truck drivers, migrant workers, and business travelers.

-

STI Management (5 min)

STIs increase the risk of contracting or transmitting HIV infection; therefore, early diagnosis and treatment of all STIs is very important. Below are the three approaches to STI management. Tap on each of the tabs to learn more.

Aetiological

This approach involves identifying causative agents through laboratory methods. Treatment is specific to the organism, and this approach is often seen as the best approach in medicine.

Clinical

In this approach, diagnosis is arrived at clinically through experience, and treatment is targeted at the suspected causative agent.

Syndromic

This approach is used in areas where resources are limited. This approach is based on the identification of a clinical syndrome, and treatment targets all causative organisms which can cause the particular syndrome.

A syndromic diagnosis is made after careful history taking and examination, and diagnosis is based on presence of collection of symptoms and signs. There is no need for laboratory backup. In this approach, treatment usually caters for more than one pathogen.

The advantage of this approach is that it is simple to use and implementable on a large scale in all health care centres. A broad range of health workers can use this method as it allows for diagnosis and treatment at one visit, and mixed infections are catered for. However, this approach has its major disadvantages: There is a degree of overtreatment, which may have a bearing on costs. It requires special attention to microbial drug sensitivity monitoring on regular basis, does not identify asymptomatic STIs, and requires intensive training.

-

History Taking (5 min)

History taking in a client with a possible STI

Due to the sensitive nature around the subject of STIs, there are several challenges in consulting with such clients. Some of these challenges are that clients are often embarrassed by presenting with genital symptoms, they are afraid about the HCW’s attitude (e.g., that they may be judgmental), and they may be concerned about being overheard.

For a successful consultation process, a health care worker must provide a conducive environment with adequate privacy. Confidentiality must be assured and maintained at all times. Keep a non-judgmental attitude and use open-ended questions. Examine clients in a clean environment with adequate light.

When evaluating a client with an STI, your goals are to:

- Establish syndromic diagnosis.

- Screen for HIV and syphilis in all clients with STIs.

- Offer appropriate antimicrobial therapy to the index client.

- Treat the client.

- Do contact tracing and treat secondary contacts. (Anex contact tracing contact tracing slip).

- Assess risk behaviour.

- Educate the client to prevent further infection.

A brief review of systems must be done to check for problems in other systems, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, cervical smear history and results, contraception type, and any recent pregnancy, delivery, or abortions. A detailed sexual history must be obtained highlighting the following key issues:

- Establish sexual orientation

- Identify sexual partner(s) symptoms

- Find out dates of most recent sexual encounter

- Ask about any history of money/gifts being exchanged for sex

- Ask about types of sex practised:

- Penetrative sex or not

- Whether condoms were used

- What sort of sex practised (vaginal, anal, orogenital, or mutual masturbation)

Common symptoms of STIs include:

- Burning or frequency of micturition

- Urethral discharge in men

- Vaginal discharge

- Swelling and/or pain in the groin

- Sores around the genitals and anus

- Lower abdominal pain in women

- Painful vaginal intercourse

- Rectal discharge or pain

- Difficulties with urination or defecation

- Itching and/or discomfort in the perineum, peri‐anal, and pubic areas

- Non-itchy skin rash or warty lesions

-

Physical Examination (5 min)

Physical examination enables the clinician to confirm the symptoms which the client has described, and to check for clinical signs of STIs. It also enables any other problems that may not have been mentioned by the client to be discovered during the examination. It is essential to explain to the client what the examination entails and to obtain their consent.

Examination of Males

Males can be examined while lying on a couch or while standing upright with underpants lowered down to the knees.

- Proceed to inspect and palpate the external genitalia for any abnormalities.

- Retract prepuce to look for redness, rash, discharge, warts and ulcers on the glans penis.

- Milk urethra if obvious discharge is not seen.

- If there are discharges or ulcers, take swabs at this point.

- Both the scrotum and testes should be carefully palpated with the aim of ruling out any swelling, masses and pain.

- Perform trans-illumination test when applicable.

- Palpated the inguinal areas and the femoral triangles to check for lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis.

- The peri‐anal area should be visually inspected for any lesions.

Examination of Females

Explain to client what you are going to do and the need for a chaperon.

- Ask client to empty her bladder.

- Client should undress and lie on the couch.

- Cover her with a clean drape and help her position legs in lithotomy position.

- Direct light source to view external anogenital area.

- Palpate inguinal and pubic areas for any lymph nodes or masses.

- Perform a speculum exam (use a Cusco bivalve speculum) and take swabs at this point.

- Carry out a bimanual exam to detect any cervical excitation tenderness or masses due to pregnancy or tumours.

Counseling Clients with STIs

When counseling clients with STIs, it will be important to understand how they became infected. You’ll want to cover the nature of their infection and the possible complications. Stress the importance of treatment compliance and attending all follow-up examinations and the need to abstain from sexual activity until they are cured. Be sure to educate your clients on the importance of partner notification, treatment, and how to prevent reinfection in the future (such as through the proper use of condoms).

-

Specific STIs and Syndromes (5 min)

Fadzai is a 22-year-old student from a local university and has come to you at the local clinic for assistance. She is single and has never been married. She admits to occasional unprotected sex with different men. Recently she has noticed several very painful small ulcers and blisters on her external genitalia.

Fadzai is experiencing one of the most common symptoms associated with and STI. The major categories of STI syndromes include urethral discharge syndrome, vaginal discharge syndrome, genital ulcer disease, lower abdominal pain, scrotal swelling, inguinal bubo, opthalmia neonatorum, balantis, and balano-prostatis.

Let’s take a look at some of the most common STI syndromes, the STIs associated with these syndromes, and their recommended treatment so you can find out the possible causes of Fadzai’s symptoms and what blood tests you would offer her.

-

Urethral Discharge Syndrome (UDS) (5 min)

Urethral Discharge Syndrome (UDS) often presents with secretion from the anterior urethra, often associated with dysuria. The duration of the symptom varies, but usually lasts several days.

Diagnosis:

- Do not base diagnosis on history alone (such as if the patient had unprotected sex).

- It is important that the discharge be observed on inspection, and, if not apparent, the urethra must be gently massaged from the ventral part of the penile shaft toward the meatus to milk out any discharge.

Causes:

- Gonococcal: N. Gonorrhoeae

- Non-gonococcal

- Chlamydia trachomatis (15-40%)

- Mycoplasma genitalium (15-25%)

- Trichomonas vaginalis (5-15%)

- Ureaplasma urealyticum (‹15%)

- Others (HSV, E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus)

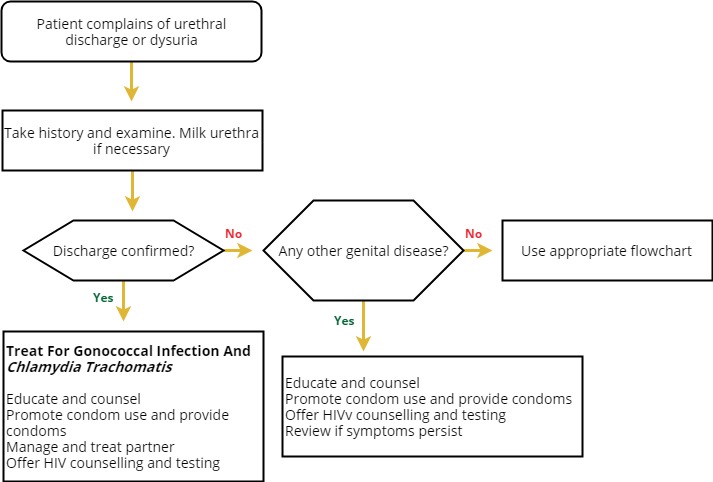

Urethral Discharge Flowchart

Tap on each tab to learn about each type of UDS.

N. Gonohoea (Gonococcal Infections)

Asymptomatic and minimally symptomatic infections occur in the community. Concurrent C. trachomatis infection is commonly (15-25%) reported. Incubation period is 2-7 days.

Paraurethral abscess Periurethral abscess Cowper’s gland abscess Conjunctivitis Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment - Urethral discharge

- Dysuria

- Urgency

- Frequency

- Haematuria

- Ensure good history taking, examination and specimen collection for lab investigations.

- Gram staining will show negative intracellular diplococci.

- Other tests to diagnose gonorrhoea are:

- Culture

- Monoclonal antibody tests

- NAAT

Drugs that can be used in the treatment of gonorrhoea are:

- Quinolones (ciprofloxacin, norfloxacin)

- Cephalosporin (ceftriaxone)

- Aminoglycosides (kanamycin)

Non-gonococcal urethritis (NGU)

40% attributed to chlamydia trachomatis. Other causes are from bacteria: Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum; from protozoa: Trichomonas vaginalis; from viruses: HPV, HSV; and from parasites (helminths): Schistosoma haematobium.

Chlamydia trachomatis

This is a gram negative obligate intracellular bacterium, which is a common cause of post-gonococcal urethritis. Incubation period is between one to three weeks. Complications are the same as for gonococcus, except that dissemination is unusual. Chlamydia can also cause Reiter’s syndrome—triad consisting of urethritis, arthritis and conjunctivitis.

Symptoms Treatment - Urethral discharge

- Dysuria

- Frequency and urgency.

Medicines that can be used for the treatment of chlamydia are:

- Doxycycline

- Erythromycin

- Azithromycin

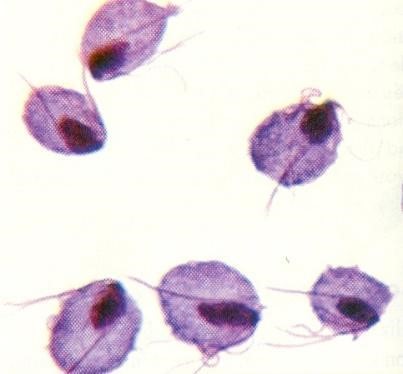

Trichomonas Vaginalis

T. vaginalis is a flagellated protozoon. Micro and culture studies showed an association of T. vaginalis with NGU. It is found in urethra of both symptomatic and asymptomatic men by a Nucleic Acid Amplification Test or NAAT. T. vaginalis is an important cause of NGU among African men.

Syndromic Approach to Managing UDS

Treatment should address gonorrhoea and chlamydial infection and consider M. genitalium and T. vaginalis infections.

First Line Drug Codes Adult dose Frequency Duration Ceftriaxone C V 250 mg im stat one dose Doxycycline C V 100mg Twice a day 7 days -

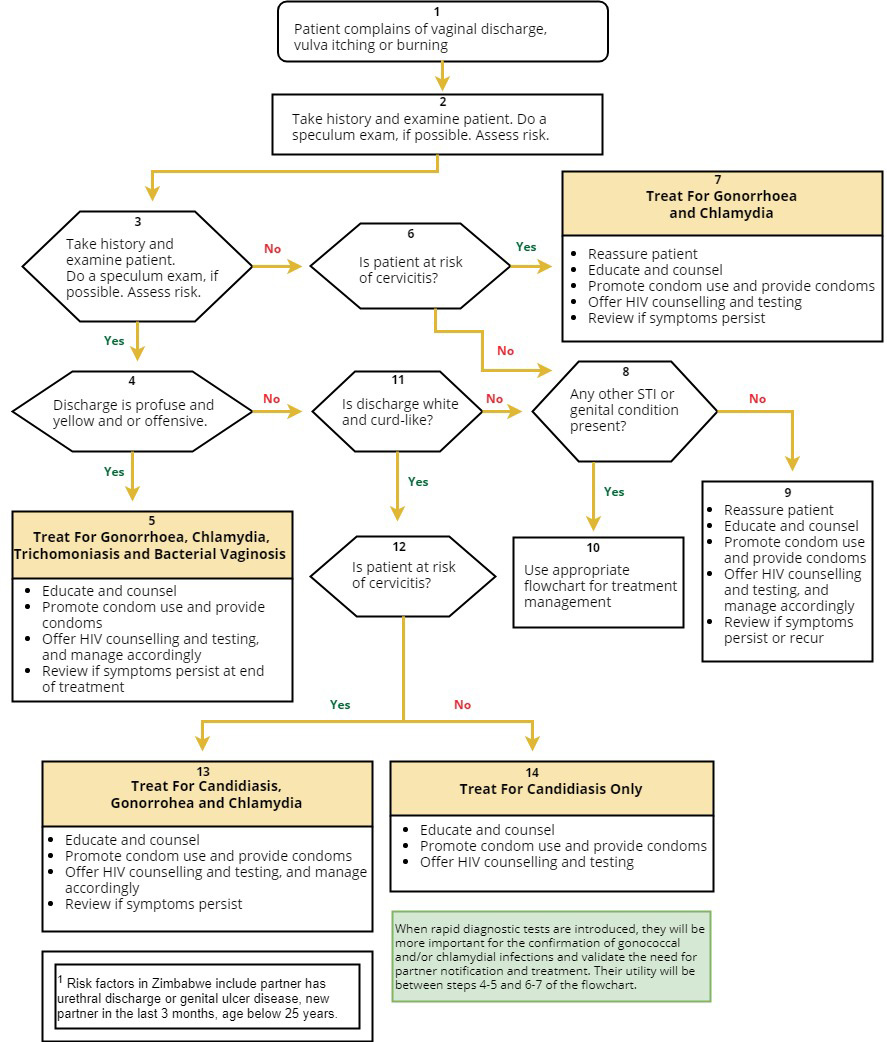

Vaginal Discharge Syndrome (VDS) (5 min)

VDS presents in sexually active female clients mainly as an abnormal vaginal discharge. Women usually present with complaints of the genital area being wet more often than usual, requiring the need to change underwear or use extra pads, or foul-smelling vaginal discharge. VDS is commonly caused by vaginitis or cervicitis. Some physiological causes of vaginal discharge include puberty, premenstrual phase, pregnancy, sexual arousal, contraceptive use, and non-pathological lesions on cervix (e.g., polyps).

Pathological causes should be suspected when discharge is excessive (other than pre- and post- menstruation), the colour changes to creamy yellow or purulent, it is malodorous, or there is vulval itchiness.

Pathological causes include:

- Vaginitis: Candida albicans, T. vaginalis, G. vaginalis, anaerobic organisms

- Cervicitis: N. Gonorrhoea, Chlamydia trachomatis

- Uterine: N. Gonorrhoea, Chlamydia trachomatis

- Other cervical herpes/warts or chancre

Risk assessment for cervicitis should include a detailed sexual history (e.g., number of sexual partners, condom use, below 25 years of age, history of coital or post-coital bleeding, presence of dyspareunia).

Vaginal Discharge Flowchart

Vaginal Candidiasis

Candidiasis can be a result of many factors and not necessarily acquired sexually. Predisposing factors include:

- Uncontrolled diabetes

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics

- Pregnancy

- Immunosuppressive therapy or disease

- Oral contraceptive use

- Poor personal hygiene

Symptoms Diagnosis Treatment In up to 20% of women, vaginal candidiasis may be asymptomatic. Possible symptoms include:

- Non-offensive white curdy discharge

- Vulval irritation/soreness

- External dysuria

- Superficial dyspareunia

- On examination: vulval erythema (redness), excoriations from scratching and vulval oedema On examination: vulval erythema (redness), excoriations from scratching and vulval oedema

Diagnosis is usually made clinically. Treatment is systemic antifungals, e.g., fluconazole. Topical antifungals are expensive and not very effective, leading to high rates of recurrence. Fluconazole 400 mg as a stat dose has been shown to be effective.

Treatment of partners is not recommended but may be considered for women with recurrent infection.

Bacterial Vaginosis (BV)

BV occurs when the normal flora of vagina are replaced by anaerobic bacteria. The organisms that have been implicated in BV are:

- Gardnerella vaginalis

- Bacteroides

- Mycoplasma hominis

- Mobiluncus species

The cause of microbial alteration is not fully understood. It is an endogenous reproductive tract infection. Sexual transmission of the disease is not proven, and hence, treatment of sexual partners has not been demonstrated to be beneficial. Predisposing factors, such as antiseptic or vaginal douching should be stopped.

Symptoms Treatment - Greyish, foul-smelling discharge with fishy odour

- Vulval irritation/soreness

The recommended treatment is metronidazole, clindamycin tablets, or clindamycin cream 2%. -

Genital Ulcer Disease (GUD) (10 min)

Genital ulcer disease is characterized by genital sores and is usually a sexually transmitted infection, including genital herpes, syphilis, and chancroid. Genital ulcer diseases increase the risk of sexual transmission of HIV.

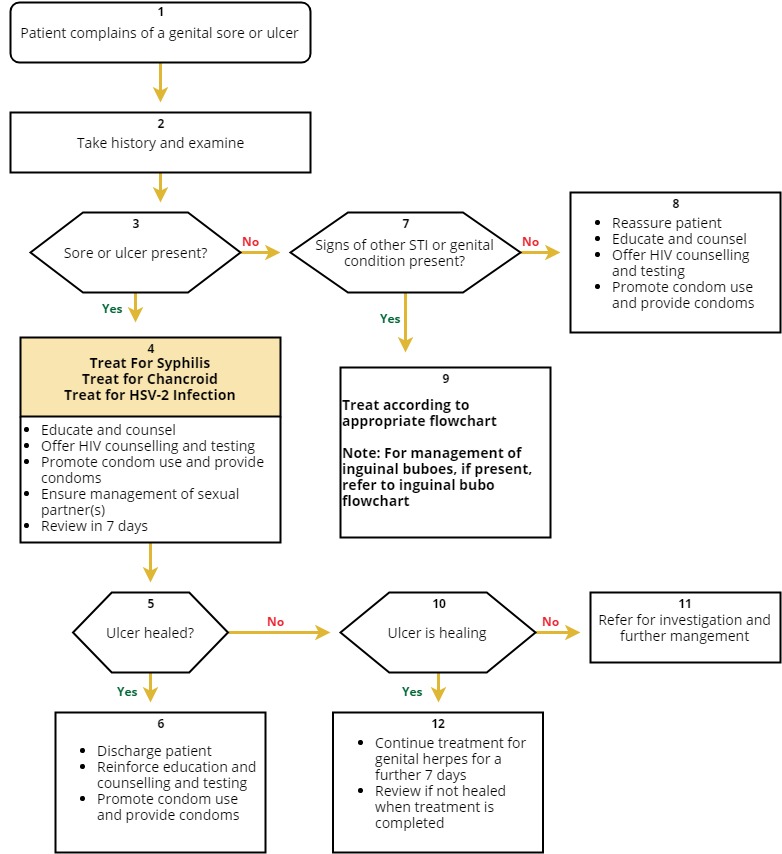

Genital Ulcer Disease Flowchart

Genital Herpes

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) infection leads to development of multiple genital ulcers. HSV infection increases the risk of transmission and acquisition of HIV infection. Recurrent or persistent genital ulcers caused by herpes simplex virus are common in PLHIV, and they are often multiple and extensive. Extra-genital or perianal ulceration can also occur.

HSV 1 is primarily responsible for orofacial ulcers and HSV 2 is primarily responsible for genital ulcers.

Transmission

- Sexually transmitted by direct physical contact.

- Sexual anal intercourse; orogenital or oroanal contact.

- Chances of transmission higher if infected partner has herpetic lesions at the time of contact.

Diagnosis

- HSV infection may be asymptomatic or present as genital ulcers.

- 90% of clients with symptomatic HSV-2 develop recurrences within 12 months.

- Ulcers heal in one to two weeks and systemic symptoms are rare.

- Depending on site of the lesions, client may present with dysuria, urinary retention, discharge, and constipation.

- Precipitating factors for recurrence include emotional stress, anxiety, sexual activity, menstruation, fever, and trauma.

- Several complications may occur due to HSV infection, such as, sacral radiculitis (constipation, difficulties in micturition, paraesthesia), systemic meningitis, encephalitis, and secondary infection leading to scarring.

- Complications are more severe in immunocompromised host.

Treatment

There is no curative treatment, and in Zimbabwe the drug of choice is acyclovir. HSV in pregnancy may increase risk of dissemination, and may complicate the pregnancy, leading to foetal loss. To prevent infection of baby during labour, ceasarian section is recommended in a client who develops a primary attack in the third trimester.

Severe genital herpes may require treatment of primary episode or suppression of recurrences with an antiviral drug, such as acyclovir. Such an intervention has also been shown to reduce lesional shedding of both HIV and HSV. Condom use is the best way to prevent HSV infection.

Syphilis

Syphilis is a systemic illness caused by T. Pallidum. Syphilis can have atypical presentation, with a tendency to rapidly progress to neurosyphilis in persons who are immune-compromised by HIV infection. Lesions of primary syphilis may be multiple, painful, or atypical.

Co-infection of syphilis with other genital ulcer organisms, for example, herpes simplex virus, is not uncommon in persons infected with HIV. Laboratory tests, such as the specific and the non-specific treponemal serologic tests for syphilis, may be non-reactive in the presence of infection with T. pallidum in a person living with HIV.

Syphilis can be classified into two broad groups: congenital and acquired syphilis. Both groups can be divided into early and late syphilis, depending on the duration.

Transmission is via sexual intercourse, transplacental infection of the foetus, or blood transfusion (in rare instances).

Symptoms Early congenital syphilis (skin) Late congenital syphilis - Bullous skin lesions

- Papulo-squamous rash

- Condylomata lata

- Skin fissuring at angles of the mouth, nostrils, and anus

- Alopecia

- Laryngitis

- Saddle nose

- Raghades

- Corneal opacities

- Teeth and bone abnormalities

- Painless swelling of the joints

- Nerve deafness

Diagnosis Treatment Non-specific tests include VDRL and RPR:

- Tests become positive 5-13 weeks after infection and become negative 12-24 months after adequate treatment.

Specific tests include TPHA, FTA-Abs:

- Tests become positive three to five weeks after infection and remain positive for life.

- These are good diagnostic but poor prognostic tests.

- False positive results are rare.

- Benzathine penicillin and doxycycline

- Erythromycin is also effective.

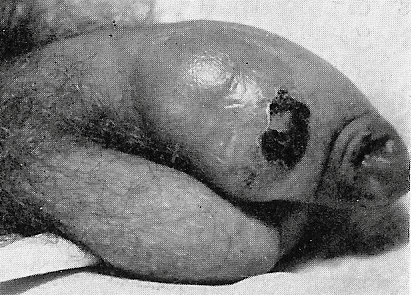

Chancroid

The bacterium Haemophilus ducreyi causes chancroid. It attacks the tissue and produces an open sore (sometimes referred to as a chancroid or ulcer) on or near the external reproductive organs of men and women. The ulcer may bleed or produce a contagious fluid that can spread bacteria during oral, anal, or vaginal intercourse. Chancroid may also spread from skin-to-skin contact with an infected person.

Atypical lesions of chancroid are common in PLHIV. The lesions tend to be more extensive, or multiple lesions may form that are sometimes accompanied by systemic manifestations, such as fever and chills. Chancroid can also present as “nonreactive chancroid” with no bubo formation.

There are suggestions that HIV infection may increase rates of treatment failure in chancroid, especially when single-dose therapies are given. Hence all HIV-positive clients with chancroid should be monitored closely, and single-dose treatment should be avoided.

Diagnosis Treatment - Take sample of fluid that drains from sore and send to lab for analysis

- Diagnosing chancroid is currently not possible through blood testing.

- Erythromycin, ciprofloxacin, and azithromycin may be used

-

Opthalmia Neonatorum (5 min)

Ophthalmia neonatorum, also known as neonatal conjunctivitis, occurs in babies during the first month of life. The infection causes redness of the eyelids and may be accompanied by swelling and purulent discharge from the eyes. If the infection is caused by N. gonorrhoeae it can affect the cornea (keratitis) and put the child at risk of becoming blind, especially if treatment is delayed or not provided. Occasionally the eye can be destroyed totally (panophthalmitis). Ophthalmia neonatorum caused by C. trachomatis and other pyogenic bacteria does not usually cause keratitis or panophthalmitis.

Ophthalmia neonatorum is entirely preventable, and all attempts should be made to prevent its occurrence by early detection and effective treatment of maternal infections and routine application of appropriate antimicrobial ointment into the eyes of the neonate immediately after delivery.

As soon as the baby is born, the eyes and face must be cleaned with dry cotton wool and the antimicrobial agent applied to the eyes. Best results are obtained if the antimicrobial agent is applied within six hours of birth, but babies presenting later should not have treatment withheld.

Diagnosis Treatment - Take history of the neonate from the mother, in terms of type of birth and where the baby was born, as well as any infections experienced by the mother during pregnancy.

- Examine the baby for:

- Reddish conjunctiva

- Swelling/oedema of the eyelids

- Purulent eye discharge

- Treat neonate according to appropriate flowchart. With systemic treatment for the baby, there is no need to instill an eye ointment, but excessive pus can be washed or irrigated with normal saline to give immediate relief and as a hygienic measure.

- Treat both parents for N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis.

- Ensure compliance with medication.

- Provide health education.

- Counsel the mother and discuss HIV testing for her and father of the child.

- Advise to return after three days for follow-up or earlier as the need arises.

-

Human Papilloma Virus (HPV) (5 min)

The Human papillomavirus (HPV) is a small DNA virus and is the most common viral infection of the reproductive tract. There are over 150 types of HPV and many do not cause disease. HPV is sexually transmitted, but penetrative sex is not required for transmission. Skin-to-skin genital contact is a well-recognized mode of transmission.

Most sexually active women and men will be infected at some point in their lives, and some may be repeatedly infected. The peak time for acquiring infection for both women and men is shortly after becoming sexually active.

HPV produces exophytic genital warts that may be large and extensive, with an increased tendency to produce epithelial dysplasia and cervical cancer in people who are immune-compromised by HIV infections. HIV-infected individuals have a higher incidence of cutaneous and anogenital warts. Some studies have shown that pre-existing HPV infection is associated with a two-fold increase in the risk of HIV acquisition in women. It has been recognized that HIV-infected people are more likely to have HPV infection, carry a greater number of types of HPV, and are less likely to spontaneously clear HPV infection.

Diagnosis and Treatment

HPV infections usually clear up without any intervention within a few months after acquisition, and about 90% clear within two years. A small proportion of infections with certain types of HPV can persist and progress to cancer. Nearly all cases of cervical cancer can be attributable to HPV infection. Though data on anogenital cancers other than cancer of the cervix are limited, there is an increasing body of evidence linking HPV with cancers of the anus, vulva, vagina, and penis. Although these cancers are less frequent than cancer of the cervix, their association with HPV make them potentially preventable using similar preventative strategies as those for cervical cancer.

Non-cancer-causing types of HPV (especially types 6 and 11) can cause genital warts and respiratory papillomatosis (a disease in which tumours grow in the air passages leading from the nose and mouth into the lungs). Although these conditions very rarely result in death, they may cause significant occurrence of disease.

-

Cervical Cancer (5 min)

An estimated 500 000 women develop cervical cancer and up to 300 000 women die every year. 80% of invasive tumours are diagnosed in low and middle-income countries. Due to lack of a national screening programme and financial constraints faced by many women, the majority of patients present with advanced disease.

With the introduction and subsequent rollout of the national OI/ART programme since 2004, the majority of HIV-infected women are able to access ART services, and their lives are being prolonged. This will allow the development of cervical cancer in women infected with oncogenic HPV.

The risk factors include:

- HIV infection

- HPV infection

- STI history

- Cigarette smoking

HPV and Cervical Cancer

Of the 150 types of HPV, forty are known to infect the genital tract and eighteen are highly oncogenic. The oncogenic types include types 16 and 18.

Cervical cancer develops in the presence of oncogenic HPV. HIV changes the natural history of HPV infection in that there is a 10 times greater incidence of cervical dysplasia and a 5 times greater prevalence of cervical neoplasia in HIV-infected women. It takes 15 to 20 years for cervical cancer to develop in women with normal immune systems. It can take only 5 to 10 years in women with weakened immune systems, such as those with untreated HIV infection.

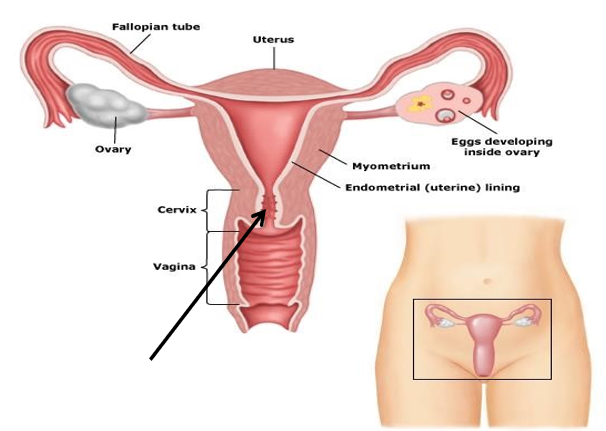

This diagram shows the transformation zone where cervical cells undergo dysplasia. If the infection is not cleared due to HIV-related immune suppression, there is rapid progression to neoplasia.

Staging for Cervical Disease

The staging system for early cervical disease is based on the histological diagnosis and the clinical manifestations of cervical cancer depend on the stage of the disease.

Early stages may be completely asymptomatic, but as the disease progresses, symptoms often include abnormal vaginal bleeding, post-coital bleeding, watery, mucoid, or purulent and malodorous vaginal discharge.

In the later stages, symptoms include pelvic or lower back pain, bowel symptoms, such as pressure- related complaints or bloody stools, and urinary symptoms, such as haematuria or vesico-vaginal fistula. Cervical cancer spreads initially locally to the uterus, vagina, parametria, peritoneal cavity, bladder, and rectum. Lymphatic spreads to the pelvic lymph and para-aortic lymph nodes. Haematogenous spread to the lung, liver, bone, and brain occurs late in the course of the disease.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of cervical cancer can be made prior to invasive disease occurring; this is the reason why screening should be incorporated into routine care for all women, especially those infected with HIV. If regular screening is conducted, early detection and treatment of HPV infection will result in a substantial reduction of morbidity and mortality. All HIV-infected women should have a papanicolaou (PAP) smear every six months for the first year after diagnosis of HIV. If these smears are negative, and the woman has no other risk factors for cervical cancer, the PAP smear should be done annually.

Diagnosis Treatment - Papanicolau (PAP) smear or liquid based cytology provides a histological diagnosis for cervical disease.

- Visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA).

- Colposcopy may be performed, which also provides the opportunity for obtaining a histological specimen.

- Conisation of the cervix of LEEP.

- HPV testing for high-risk HPV types (i.e., 16 and 18).

Destructive methods:

- Laser-vaporisation

- Cryotherapy

- Thermo-coagulation

Non-destructive methods:

- Loop electrosurgical excision (LEEP)

- Knife conization

- Hysterectomy

The prevention of cervical cancer involves behaviour change initiatives as for any sexually transmitted infection and, very importantly, vaccination. Vaccination against specific HPV types protects women from infection and progression to cervical cancer. To date, two vaccines have been developed and approved:

- Gardasil, which covers HPV types 6,11,16 and 18

- Cervirax, which covers HPV types 16 and 18

Some problems include the fact that HPV vaccination does not cover other HPV types, is much less effective in people already HPV-infected, and the vaccine is expensive.

-

Complications of STIs (4 min)

The majority of complications of STIs are preventable if the client is diagnosed and treated early. However, failure to diagnose and treat STIs at an early stage may result in serious complications. The most serious health consequences of STIs tend to occur in women and newborn children. Tap on each tab below to learn more.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease (PID)

Some of the serious consequences of reproductive tract infections in women occur when an infection of the lower genital tract (cervix or vagina) reach the upper genital tract (pelvic region), causing inflammation of the inner lining of the uterus (endometritis), the fallopian tubes (salpingitis), the ovaries (oophoritis), or even further up in the abdomen, causing a peri-hepatitis. The infection may become generalized (bacterial septicaemia) and life threatening. The resulting tissue damage and scarring of the pelvic structures may cause infertility, chronic pelvic pain and increased risk of ectopic pregnancy. Aetiological pathogens commonly associated with PID include N. gonorrhoeae, Chlamydia trachomatis (C. trachomatis), mycoplasmas, anaerobic bacteria, gram-negative facultative bacteria, and streptococci.

PID permanently scars and narrows the fallopian tubes and increase the risk of ectopic pregnancy by 7- to-10 fold compared with women who have not had PID in their life. Ectopic pregnancy can be fatal for women because the tubes rupture, causing extensive internal haemorrhage. Without treatment, 55% to 85% of women with PID may become infertile. Many women may lose their fertility without ever realizing they had PID.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Flowchart

Infertility

Infertility often follows untreated pelvic inflammatory disease in women, and epididymitis and urethral scarring in men. Complications of STIs are the most important preventable causes of infertility in regions where childlessness is most common. Repeated spontaneous abortion and stillbirth, often due to STIs, such as syphilis, are other important reasons for couples failing to have children.

Ectopic pregnancy

PID increases the risk of ectopic pregnancy by 10-fold. The tubal scarring and blockage that often follow PID may be total or partial. Fertilisation may still occur with partial tubal blockage but creates the risk of foetal implantation in the fallopian tubes or other sites outside the uterus. Ruptured ectopic pregnancy, along with complications of abortion and postpartum infection, are common preventable causes of maternal death in places with high prevalence of STIs and other reproductive tract infections (RTIs).

Genital cancers

Some types of the human papillomavirus (HPV) are sexually transmitted. Some of them, such as HPV types 16 and 18, greatly increase the risk of cervical cancer, a leading cause of cancer deaths in women.

Other Complications

Complications in men with repeated urethritis include urethral strictures and abnormal sperm morphology (form and structure) and motility, leading to reduced fertility. Complications in newborn babies include the following:

- Congenital syphilis

- Gonococcal infection of the conjunctiva (ophthalmia neonatorum) – a potentially blinding condition if treatment is given late or absent

- Chlamydial pneumonia

- Perinatal hepatitis B infection

Measures for preventing these four manifestations of sexually transmitted pathogens in neonates have been classified among the most cost-effective measures for preventing neonatal morbidity and mortality.

-

Fadzai (5 min)

Let’s revisit Fadzai’s case. She is a 22-year-old student from a local university. She is single and has never been married. She admits to occasional unprotected sex with different men. Recently she has noticed several very painful small ulcers and blisters on her external genitalia. She has come to you at the local clinic for assistance.

-

Knowledge Check (10 min)

-

Key Points (5 min)

- HIV infected individuals are at a greater risk of acquiring STIs than HIV negative people. All people with STIs must be offered an HIV test.

- STIs can present as different syndromes.

- Zimbabwe uses the syndromic approach to treatment and management of STIs.

- Early, effective management of STIs is essential so as to prevent the development of long term debilitating complications.

- Cervical cancer is preventable and all sexually active women must be offered routine screening (VIAC or PAP smear) especially HIV infected women.