Session 9: Tuberculosis and HIV Co-Management

Prevention, Care, and Management

In this session, you will learn about treatment regimens for clients with TB and special techniques for managing children.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- Describe TB infection control.

- Explain how to control TB in congregated settings.

- Identify steps to follow when conducting contact investigations.

- Describe TB treatment categories and regimens.

- Describe how to care for and monitor clients on TB treatment.

- Describe the TB treatment outcomes.

- Identify signs and symptoms related to TB in children.

- Describe the diagnosis of TB in children.

- Describe treatment and care of TB in children.

Learning Activities

-

TB Infection Control (15 min)

TB infection control (TBIC) measures reduce TB transmission in health-care facilities, congregate settings , and households. In the absence of appropriate infection control policy and practice, there is a high risk of transmission and spread of TB in areas in which people live and work. The greatest risk of transmission occurs when TB clients remain undiagnosed and untreated, including those with latent TB infection (LTBI). For this reason, screening all clients who may have active TB and if appropriate diagnosing and treating them early is paramount for reducing transmission. It’s important to remember that because TB is spread from person to person through the air, everyone is at risk of TB infection.

A plan to prevent transmission of TB in a health care facility should be part and parcel of the overall facility infection prevention and control (IPC) programme. The plan should be guided by the Zimbabwe National Infection Prevention and Control policy. All health care facilities should develop and implement a facility specific TB infection control plan designed to provide:

- Prompt identification of presumptive cases of TB

- Appropriate, non-stigmatizing, immediate separation of presumptive cases or infectious TB cases from other clients.

- Prompt testing of presumptive cases for infectious TB with rapid and specific tests such as the GeneXpert.

- Prompt initiation of treatment of ALL TB cases (and esp bacteriologically confirmed cases of infectious TB).

- Appropriate and sustained implementation of simple but effective environmental infection transmission prevention measures.

- Appropriate use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Continuous monitoring and periodic evaluation of the TBIC plan.

As explained earlier in this session, the TB infection control programme is based on a three-level hierarchy of control measures. Managerial and administrative controls are a first priority in any IC plan and are intended to reduce the risk of exposure to infectious aerosols. Environmental (engineering) controls are the second tier level of control which are intended to reduce the concentration of infectious aerosols and prevent their spread in the health care facility. Personal level (respiratory protection) controls are the third tier and will not completely protect the user from inhaling infectious aerosols in areas where the concentration of droplet nuclei cannot be adequately reduced by administrative and environmental controls.

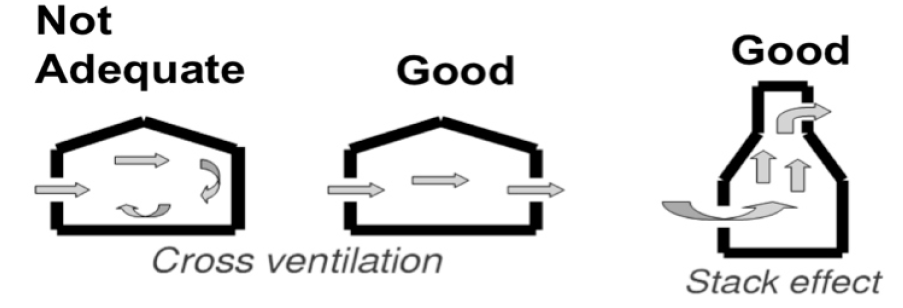

While it’s often not possible to completely eliminate the exposure to infectious droplet nuclei, various environmental control methods can be used in high-risk areas to reduce the concentration of droplet nuclei in the air. One measure that is extremely effective is to keep facility windows and doors open at all times when providing care to clients, even during the winter and nighttime. This will maximise natural ventilation. Opening windows and doors on opposite walls will also allow for cross ventilation. The following graphic shows strategies for promoting natural ventilation:

In addition to natural ventilation strategies, there are several other strategies that can be incorporated to reduce the concentration of droplet nuclei in the air, such as:

- Reduce crowding in waiting areas and use open-air shelters with a roof to protect clients from sun and rain as waiting areas.

- Utilize an open plan in client waiting areas and wards to let in sunlight. Sunlight is a natural source of ultraviolet light, which kills TB bacilli.

- Control the direction of airflow. Fans strategically placed throughout the space will not only control airflow, but will also cause air mixing which increases the effectiveness of other environmental controls.

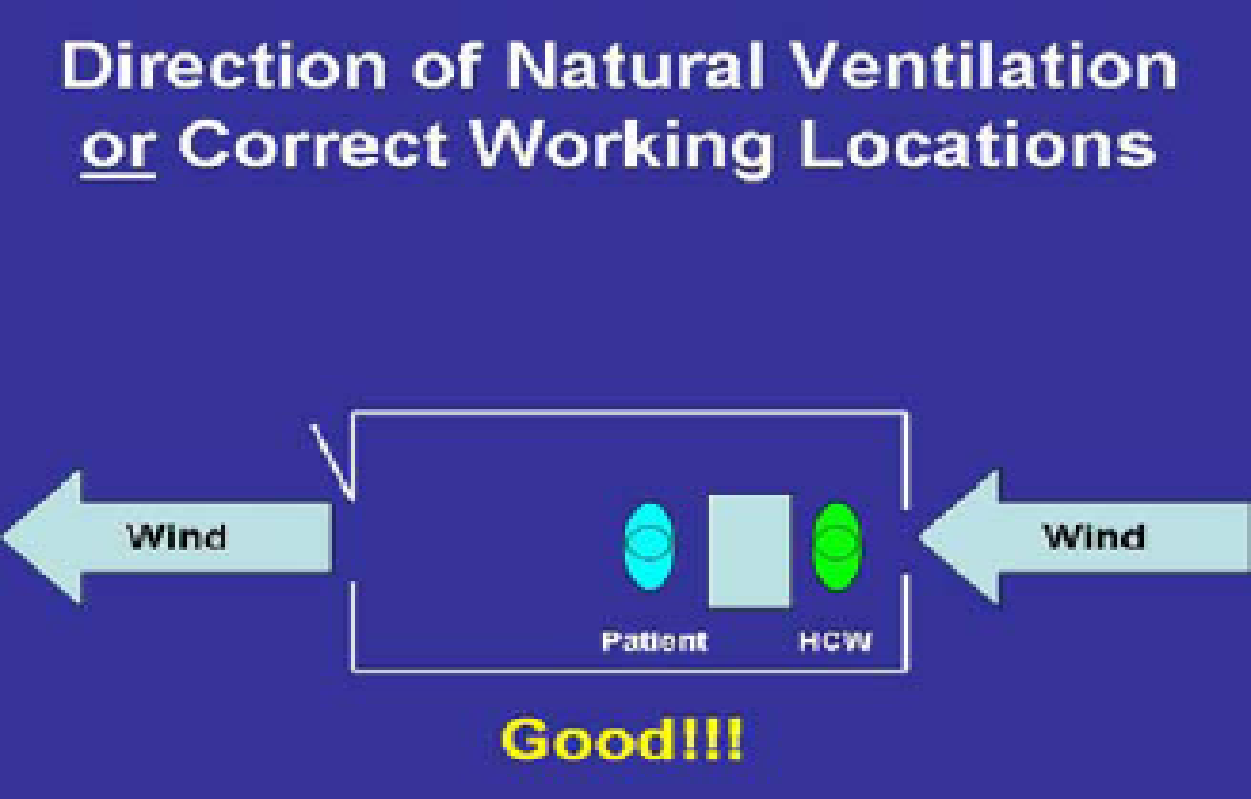

- Organize sitting arrangements in consultation rooms to avoid airflow from clients to the healthcare worker.

- Attend to one client at a time in the consultation room to minimise exposure to droplet nuclei.

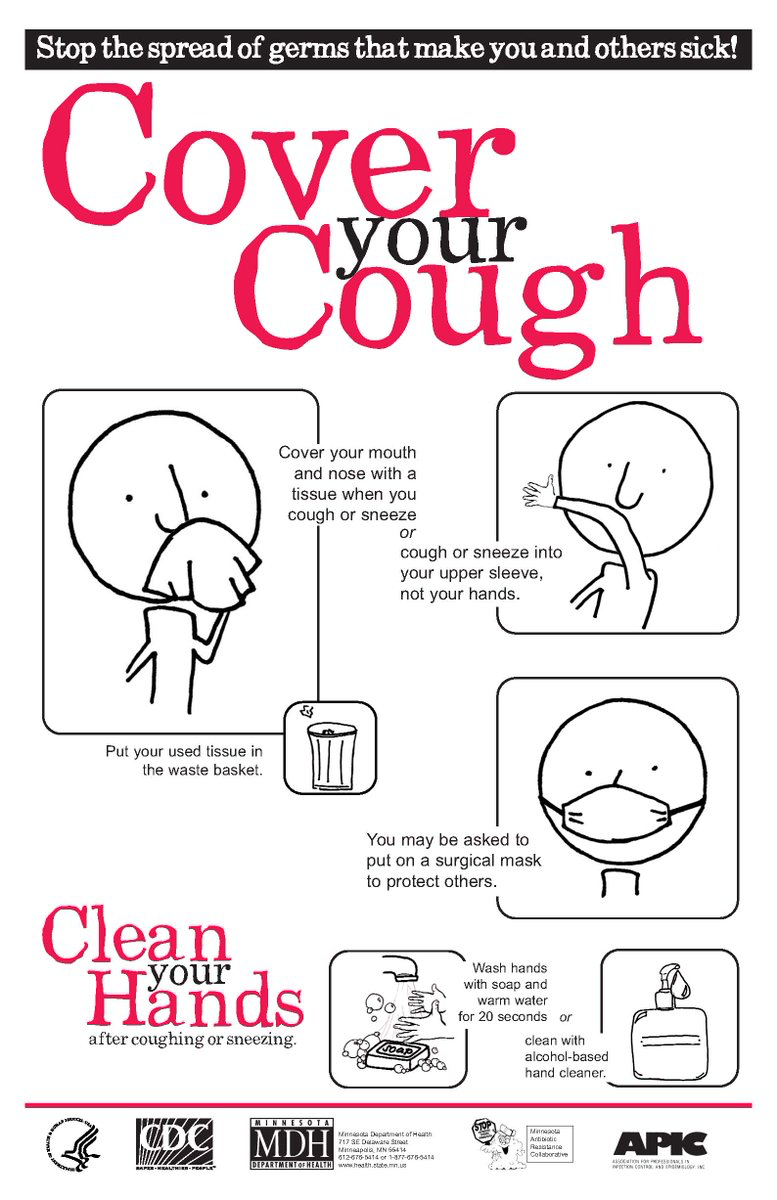

Personal respiratory protection (PPE) reduces the risk of healthcare workers inhaling infectious TB droplet nuclei and is used to protect healthcare workers when concentration of droplet nuclei cannot be adequately reduced through managerial/administrative or environmental controls. PPE is usually only used in high risk areas and situations. Healthcare workers should wear N95 respirators, which are different from surgical paper masks in that they stop particles from being released into the air and they protect the wearer from inhaling any TB droplets. Clients with active TB should instead wear surgical masks and practice cough etiquette to reduce the spread of infectious droplets.

The use of PPE should not replace less expensive administrative and environmental IPC measures. N95 masks are only indicated in specialized settings such as referral facilities or when nursing MDR-TB clients and only when all other infection control measures have been fully implemented.

Routing screening of healthcare workers for active TB

As a healthcare worker, you are at increased risk for developing TB because of repeated and prolonged exposure to clients with active TB. For this reason, it’s vital that you’re screened for active TB on a regular basis. You should receive a comprehensive TB screening that includes checking symptoms and BMI and conducting a CXR annually. Every six months you should be screened for symptoms. All non-critical staff such as administrators, drivers, and cleaners also should be screened.

Screening should be free of charge and preferably offered as part of a comprehensive wellness program that includes HIV testing and counselling services; mental health care; and screening for non-communicable diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and cancers. Appropriate linkages to care and treatment of those diagnosed should be a priority. In addition, screening, treatment, and services should be offered in a way that respects privacy and individual rights.

-

Control of TB in Congregated Settings (15 min)

The WHO defines congregated settings a “mix of institutional settings where people live in close proximity to each other.” Examples of congregate settings include prisons, holding cells, homeless shelters, and refugee camps. Even though people congregate at healthcare facilities, they do not considered part of this category.

WHO Policy on TB Infection Control in Health-Care Facilities, Congregate Settings and Households.In this section, we’ll look at how to control TB transmission in prisons, refugee camps, and other congregate settings. The three tiers of TB infection control measures discussed in the previous section also apply to medical services in congregate settings. In fact, the spread of TB is worsened by poor living conditions and overcrowding that are likely to exist in these settings, making infection control a priority. Malnutrition and HIV, which are common among inmates and residents of refugee camps, also increase the risk of TB transmission.

Therefore, to help control TB transmission in prisons, refugee camps, and other congregate settings, it is important to screen for TB on a regular basis. Screen all new inmates and arrivals at entry, interim stay, and exit from such communities to ensure early diagnosis of active TB and prompt initiation of appropriate treatment. Staff and dependents from these places should also be screened regularly (following national TB guidelines high risk screening schedules) and continue to provide TB information and HIV testing. The screening tool, BMI, and especially CXR will be used for screening such high-risk groups. Make sure there is a plan for linking the TB services for continuity post discharge into the general public TB service delivery.

Reducing TB transmission in households

The risk of transmission is at its greatest before TB is diagnosed in a household. For this reason, early case detection and prompt initiation of appropriate treatment is key to reducing household transmission.

TB contacts are anyone who has close contact with a person diagnosed with TB. Contacts usually include anyone living in the household with the client and the client’s caretakers. These contacts are at high risk for infection and for this reason should be identified and thoroughly screened for TB. This systematic process is usually referred to as a contact investigation (CI).

When conducting a contact investigation, screen all household contacts of the person diagnosed with TB. All contacts of MDR-TB clients should receive screening and if possible culture and DST on a regular basis. It’s also important to educate household contacts on basic facts about TB, how to reduce the risk of transmission, and proper procedures for coughing etiquette and respiratory hygiene.

In addition, provide the household with information related to reducing stigma towards people with active TB.

The household environment can also be managed in a way that helps control transmission. Just as with healthcare facilities, natural ventilation is a key infection control measure for households, particularly in rooms where people with TB spend a lot of time. For the first 2-4 weeks of treatment, bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB clients should spend as much time as possible outdoors or stay in well-ventilated rooms. When possible, they should avoid overcrowded and poorly ventilated spaces. Children less than 5 years old should spend as little time as possible in the same living spaces as persons with bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB. Home environment assessments should be conducted for households that contain persons with active TB, especially for households with MDR-TB clients.

-

Contact Investigation (10 min)

As explained in the previous section, a contact investigation (CI) is the systematic approach of identifying, screening, and treating (when appropriate) all known contacts of a client with TB, irrespective of the client’s bacteriological status. Each person with infectious TB has on average of 10 contacts, of which 20%–30% have latent TB (LTBI), and 1% have TB disease. Of contacts that will ultimately have TB disease, approximately 50% develop disease in the first year after exposure. To control the further transmission of TB, it’s vital to identify both adult and child contacts early and screen them for TB.

The goals of CI are first and foremost to reduce morbidity and mortality due to TB through early identification and appropriate treatment of active TB cases among contacts. CI also aims to stop further transmission by early detection of possible secondary cases. In addition, CI strives to prevent future cases of tuberculosis in the population by detecting and offering preventive therapy of infected high-risk contacts, such as children and immune compromised individuals, of index cases with active TB. Counselling families and providing individual/family education on infection control is also a goal of CI. Last, CI works to identify all close household contacts of MDR and extensive drug resistant (XDR) TB, without active disease for monitoring for at least 2 years following identification of the index patient.

Process of contact investigation

There are several systematic steps to follow when conducting a CI. Tap on each tab below to read more.

Contact information

Get information on contacts from TB patient.

The first step is to decide which clients are the highest priority to investigate, thus the index case. Every effort is made to investigate contacts of all children with TB (irrespective of site or bacteriologic status); PLHIV and adults with pulmonary and laryngeal TB (irrespective of bacteriologic status). Where priority is required, it is given to those that are bacteriologically confirmed TB cases.

Line lists

Put contacts into a line list.

The index case is then interviewed to identify contacts and the place(s) of contact.

Site visits

Conduct site visits.

Information gathered regarding the contacts and is then confirmed by a home, school, or workplace visit as appropriate.

Contact screening

Screen contacts for TB.

In order of priority, contacts are screened, first with a symptom enquiry. If feasible, contacts are invited to the health facility and are given a more thorough investigation including a CXR.

Sputum collection

Collect sputum for GeneXpert.

At the healthcare facility sputum is collected from contacts with presumptive TB for GeneXpert. Alternatively, healthcare workers and/or volunteers can collect sputum samples from contacts at home, school, the workplace, or other settings.

LTBI

Last, those contacts with latent TB are treated as appropriate.

All children and PLHIV should be assessed for TB more thoroughly, including checking for disease at extrapulmonary sites. The likelihood of the presence of other medical conditions and social factors that increase the risk of TB should be determined.

Management options after CI

Once the CI has been completed, there are three follow-up steps. First, those who are diagnosed as having active TB begin TB treatment and are registered. Next, children over 5 years and PLHIV with no evidence of active TB disease receive TB Preventive Therapy (TBPT). Last, children who are 5 years and above who are healthy receive follow ups on a clinical basis and are educated to report to the nearest health facility if they experience any symptoms compatible with active TB such as cough of any duration, fever, weight loss, or failure to gain weight.

Practice recommendations for children

If children who are close contacts of a person with pulmonary TB have a positive symptom screen, or are undernourished, or have an abnormal chest x-ray, then it is important to collect a sputum (if the child is able to produce a sputum), a NPA, and/or a NGA and/or stool specimen for GeneXpert testing. If, however, these children have a negative symptom screen and/or a normal chest x-ray, they should instead be treated with six months of Isoniazid to prevent TB. While it’s important to investigate children who are in close contact with persons with TB, it’s equally important to identify, screen, and investigate all contacts of children with TB, irrespective of site or bacteriological status.

Managing breastfeeding infants of mothers with infectious PTB

When working with a mother with pulmonary TB who is breastfeeding, your top priority should be to treat the mother with appropriate anti-TB medicines. Do not separate the mother from the baby and let the mother know that she can continue breastfeeding. In addition, screen the baby for TB using a symptom screen, nutritional assessment, a TST (if available), and a CXR. If the baby has no evidence of active TB, administer TB Preventive Therapy. If the baby has not been vaccinated with BCG, administer this vaccine at the end of the TBPT treatment.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Treatment Categories and Regimens (15 min)

From a broad perspective, there are five key goals associated with treating TB. The primary goal is to cure the client and ensure that he or she is able to have a full quality of life. The next goal, which is equally important, is to prevent death from active TB or its complications. Once TB is treated, it’s also important to prevent relapse of the disease in clients. In addition, we want to make sure that TB is not transmitted to others. The last goal is to prevent the development and transmission of drug-resistant TB (DR-TB).

See the resources section for case definitions used in the care and treatment of TB clients.

Full TB treatment

There are two phases used for providing full TB treatment. These phases are used for treating both drug-sensitive TB and drug-resistant TB. Tap on each tab to read more.

Intensive phase (IP) for drug sensitive TB

The initial, intensive phase is designed for rapid killing of actively growing bacilli and killing of semi-dormant bacilli. The duration of this phase is two months. Medication prescribed is rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol (RHZE).

Continuation phase (CP) for drug sensitive TB

This phase eliminates bacilli that are persistent and reduces the rate of failure and relapses. The duration of this phrase is between four-six months depending on the organ affected by the disease. Medication prescribed is rifampicin and isoniazid.

Drug-sensitive TB

All clients with drug-sensitive TB (TB which is susceptible to first-line medicines) are treated with a combination of first-line drugs (FLD) such as rifampicin (R), isoniazid (H), pyrazinamide (Z), and ethambutol (E). The intensive phase consists of two months of RHZE followed by a continuation phase of four months of HR. This regimen is abbreviated at 2RHZE/4HR. The medical officer may choose to extend the duration of the continuation phase for some forms of EPTB.

First-line TB treatment regimen for drug-sensitive TB

As described in the section above, the first-line regimen for treating drug-sensitive TB is 2RHZE/4HR. In 1991, WHO recommended a category two regimen for retreating clients who were previously treated for TB. This regimen added streptomycin to the first-line agents and extended treatment to eight months. With the standardization of the GeneXpert TB test, however, this regimen and streptomycin are no longer used in Zimbabwe. Instead, it’s recommended that clients have GeneXpert testing done on their sputum and if rifampicin resistance is excluded, they should be put on 2RHZE/4HR.

When working with clients who will be taking 2RHZE/4HR, let them know that anti-TB drugs are available either as single medicine formulations or as fixed dose combinations (FDCs) that include two medicines (such as rifampicin and isoniazid); three medicines (such as rifampicin, isoniazid, and pryrazinamide); or four medicines such as (rifampicin, isoniazid, pryrazinamide, and ethambutol). FDCs are better tolerated and have a lower pill burden compared to single drug formulations.

Clients with DR-TB are treated using second-line drugs (SLD), which will be covered later in this session.

Anti-TB drug dosage in adults

The dosage for anti-TB medicines is based on the client’s weight. For this reason, it’s important to weigh your clients at every visit and adjust their dosages as soon as their weight band changes to prevent under- or over-dosage. It’s likely that your clients will gain weight during their TB treatment.

The table below gives estimates of number of FDCs per kilogram of body weight based on the 2016 TB Management Training Guidelines:

Client's weight band Number of FDC tablets to be given to the client Intensive phase for 2 months with RHZE daily.(Each FDC tablet contains H 75 mg + R 150 mg + Z 400 mg + E 275 mg.) Continuation phase for 4 months with HR daily (Each FDC tablet contains H 75 mg + R 150 mg) 25 - 39 kg 2 2 40 - 54 kg 3 3 55 - 70 kg 4 4 70 kg + 5 5

Treatment of EPTB

Treatment of EPTB follows the same first-line regimen as treatment for pulmonary TB—clients receive 2RHZE during the intensive phrase and 4RH during the continuation phase. In some circumstances, for example for clients with TB meningitis or spinal TB, the clinician may choose to extend the duration of the continuation phrase as per the recommendation in the 2016 National TB Guidelines.

-

Care and Monitoring Clients on TB Treatment (10 min)

Just as with clients who are on ART, clients who are on a TB treatment regimen need to be monitored on a regular basis to evaluate their adherence to their regimen and their response to treatment. Accordingly, monitoring allows you to identify any problems that need to be addressed and take care of these problems early on.

When we talk about monitoring TB treatment, there are two main types of monitoring that are used. Tap on each to read more.

Clinical monitoring

Clinical monitoring is used with all clients. In some situations where bacteriologic monitoring is not an option, for example when working with clients with EPTB, this is the only form of monitoring available.

Clinical monitoring consists of retaking the client’s history and performing a physical examination. You will also need to check your client’s weight and gauge his or her well-being. In addition, each time you see the client, ask if previous symptoms are still present.

When working with a client who is doing well, you will notice that he or she progressively feels better. In addition, he or she will have increased energy and appetite, will gain weight, and symptoms will decrease and/or eventually disappear.

Bacteriologic monitoring

Bacteriologic monitoring is performed with follow-up sputum examinations. These examinations determine the client’s progress, indicate if the treatment is effective, and help with making decisions about changes to the treatment regimen and phase.

Bacteriologic monitoring is done through direct smear microscopy [DSM] (for drug sensitive TB) and both DSM and culture (for DRTB cases). Xpert MTB/Rif and radiography are generally not used for routine monitoring of TB patients on treatment. Clients on first-line TB treatment should have one sputum sample collected and sent to the laboratory for direct smear microscopy (DSM). If a client who previously had a positive smear now has a negative smear (seroconversion), this indicates that he or she is adhering to the treatment regimen and that the treatment is effective.

After two weeks of treatment, most clients will have sterile sputum, meaning any bacilli in it are dead. After two months of chemotherapy, more than 80% of new pulmonary smear-positive cases should be smear-negative, and after three months, the rate should increase to at least 90%.

Follow up sputum examinations are thus done at the end of two months (intensive phase); at the end of five months and at end of treatment (six or eight months). This type of bacteriologic monitoring is used on clients who are pulmonary TB cases irrespective of initial bacteriologic status while those extra-pulmonary TB cases depend on clinical evaluation to assess their adherence and response to treatment.

Directly observed therapy (DOTS) and client follow-up

While it’s the client’s responsibility to take his or her medications, it’s also the responsibility of the healthcare worker who is treating the client to ensure that he or she is successful. While monitoring is vital for treatment success, supervising the treatment throughout its duration is equally important. Directly observed treatment (DOT), which requires a supervisor to watch a client swallowing the tablets, is the recommended approach. This method ensures that clients take the right medicines, in the right doses, and complete their treatment.

Altogether, good client follow-up and ensuring an efficient DOT help to reduce poor adherence, one of the major risk factors of DR-TB. Drug resistant TB is difficult to diagnose and difficult and expensive to manage, and for these reasons, all efforts must be made to keep the incidence low.

-

Adverse Drug Events (5 min)

Adverse drug events (ADEs) of anti-TB medicines can be classified into major and minor ones and are shown in the table below. The table also includes a symptom-based approach to the diagnosis of ADEs and how to manage the events. For more detailed information see the 2016 National TB Guidelines provided in the resources section of this training.

Symptom-based approach to identifying and managing ADEs due to FLDs

ADE Drug probably responsible Management Minor ADEs Continue anti-TB medicines, check medicine doses Anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain Pyrazinamide Rifampicin Even though the NTLP recommends DOT for all TB clients in Zimbabwe, clients experiencing these minor AEs should be advised to take the medicines at night, preferably with family member DOT. Ranitidine, omeprazole, or an antacid may also be prescribed. Joint pains Pyrazinamide Give nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS), such as aspirin or ibuprofen Burning sensation in feet Isoniazid Give pyridoxine 100 mg daily Skin rash with mild itchiness, no mucous membrane involvement or blisters Rifampicin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide Chlorpheniramine 4 mg tds or promethazine 25-50 mg at night. Aqueous cream, calamine skin lotion. Peripheral neuropathy Isoniazid Pyridoxine 50 mg 1-3 times daily Orange/red urine Rifampicin Reassure client. Let client know this at the beginning of treatment (before the first dose is taken). Major ADE Management Itching of skin with rash, mucous membrane involvement, blistering Rifampicin, isoniazid, and pyrazinamide Stop anti-TB drugs. Refer to the next level if you cannot manage. Wait until the rash has resolved and resume medication at a hospital as advised below. Jaundice (other causes should be excluded) Most anti-TB medicines (especially pyrazinamide, rifampicin, and isoniazid) Stop anti-TB drugs. Do liver function tests. (See below) Test for Hepatitis A, B, and C

Vomiting and confusion: suspect drug-induced acute liver failure Most anti-TB medicines (especially pyrazinamide, rifampicin, and isoniazid) Refer to hospital for admission. Stop anti-TB medicines, do urgent liver function tests. Check for the presence of hepatitis viruses (A, B, and C) and check the prothrombin time/International Normalized Ratio (INR) Deafness (no wax on auroscopy), dizziness Streptomycin Stop streptomycin Visual impairment (other causes excluded) Ethambutol Stop ethambutol/ Refer to an eye specialist. Shock, purpura (bleeding under the skin), acute renal failure Rifampicin Stop rifampicin -

Treatment Outcomes (5 min)

At the beginning of this section we mentioned that one of the key goals for treating TB is to cure the client in a way that allows him or her to live a healthy life. To declare that a client is cured of TB is formally defined as when a client who was initially sputum-positive (either with GeneXpert testing or DSM) or culture-positive becomes sputum smear negative in the last month of treatment, and on at least one previous occasion. When we discuss treatment outcomes, there are several other terms that you will need to know for records and reporting. Tap on the following headings to learn more:

Treatment completed

A TB patient who completed treatment without evidence of failure but does not have a negative smear or culture result in the last month of treatment and at least one previous occasion.

Treatment success

Sum of patients cured and those who have completed treatment.

Treatment failure

A TB patient whose sputum smear or culture is positive at month 5 or later during treatment.

Died

A TB patient who dies for any reason before starting or during the course of treatment.

Lost to follow up (LTFU)

A TB patient who did not start treatment or whose treatment was interrupted for 2 consecutive months or more.

Not Evaluated

Last, those contacts with latent TB are treated as appropriate.

A TB patient for whom no treatment outcome is assigned. This includes cases ‘transferred out’ to another treatment unit as well as cases for whom the treatment outcome is unknown to the reporting unit.

-

Referrals and Transfers (5 min)

When working with a client who has TB, there will be times when you will need to refer or transfer the client. A referral is when a patient is sent to another unit for services. These services can be TB related or relate to other services. For example, you may need to refer a TB client for nutritional support to help him or her regain energy and improve their weight.

A transfer is when a client is moved from one TB register to another for any reason (and a transfer form should be filled in). Transfers can be from one health facility to another within the same district or from one district or province or country to another. Such patients are, however, analysed in the cohort of where they transferred from.

When transferring a client, the transfer form should be filled in triplicate—give one copy to the patient, keep one copy for your records, and send the remaining copy to the receiving TB facility. Give the client a one-week supply of drugs irrespective of the phase they are in. In addition, ensure that you obtain and record the final treatment outcomes from the receiving unit. Only indicate that a client is “Not Evaluated” on the initial register if the outcome is unknown.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

TB in Children (5 min)

Let’s start this section by looking at the global impact TB has on children. In 2015, an estimated 1.0 million children suffered from TB. This represents about 10% of all TB cases diagnosed that year. Moreover, TB in children is among the top ten causes of death in children. This is especially true in high TB burden settings like Zimbabwe. In these settings, many cases of pneumonia, malnutrition, and HIV may actually be undiagnosed TB.

For a child, the source of TB is usually an adult or adolescent family member with pulmonary TB. Children below 5 years of age are most affected by TB, quite possibly because they are likely to be in close contact with adults who have TB. Children with TB are usually discovered during contact tracing for clients with pulmonary TB especially bacteriologically confirmed TB. For this reason, if you have a child client who presents with signs and symptoms of TB, it’s best to inquire about his or her history of TB contact.

The majority of TB cases that occur in children are pulmonary TB and the presentation varies with age. In Zimbabwe, BCG vaccination given at birth protects against the severe forms of TB. HIV-infected children are at a greater risk for TB infection and TB disease, and co-infection is common in children in Zimbabwe.

Signs and symptoms of TB in children

It’s important to recognize the signs and symptoms of TB in children so that you can begin the diagnosis and treatment process early. The clinical presentation of TB in children varies with age. Infants less than 12 months and children ages 1-5 years of age are more likely than older children to have severe TB and experience rapid onset.

Children with TB typically exhibit the following symptoms:

- A cough, which is persistent and not improving on antibiotics.

- Weight loss or failure to gain weight.

- A fever and/or night sweats.

- Reduced playfulness, fatigue, and are less active.

These symptoms usually occur for more than two-three weeks despite treatment with appropriate medications such as antibiotics or antimalarials. In addition, you will often find that these children have a history of contact with someone treated for TB. Children typically develop TB within two years after exposure and 90% do so within the first year.

-

Diagnosis (15 min)

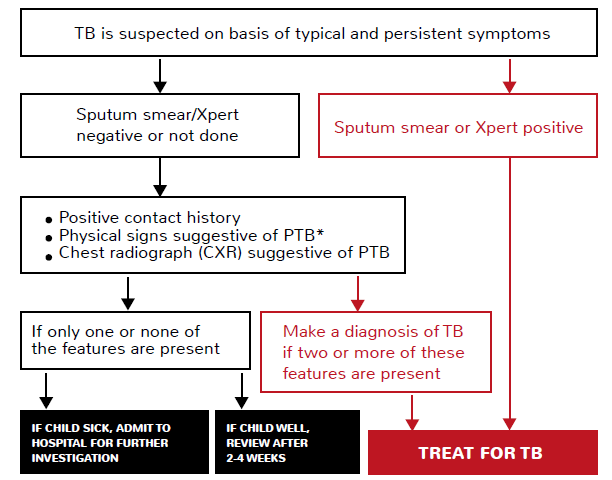

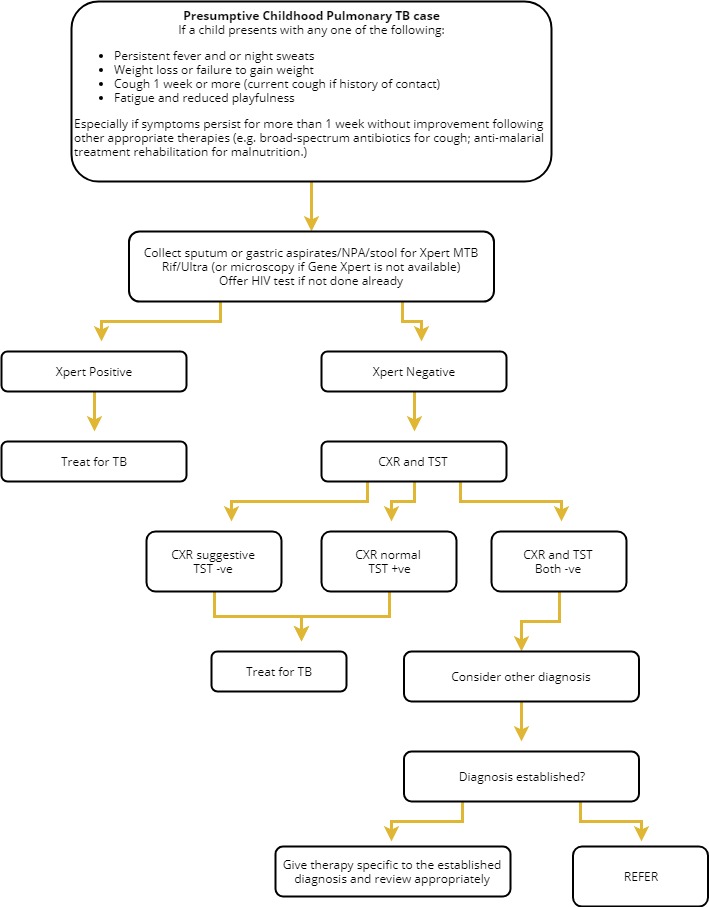

The clinical signs and symptoms of TB in children are generally non-specific, meaning that diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion. Ultimately, diagnosis relies on a thorough assessment of the information gathered from a clinical examination, taking a careful history of exposure, and conducting relevant investigations.

To aid with diagnosis, it’s important to be aware of the key risk factors for TB in children. Children who live in households with or have other close contact with individuals, who have pulmonary TB, especially bacteriologically confirmed pulmonary TB, are at risk. In addition, children less than five years of age, children who have HIV infection, children who suffer from severe malnutrition, and children who have recently contracted measles are at risk.

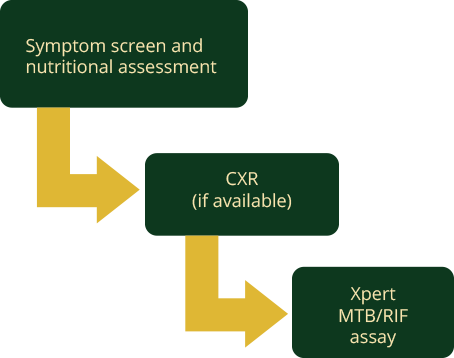

As with diagnosing TB in adults, you will want to follow an algorithm that walks you through the appropriate procedures to follow. Tap on each step to read more:

Symptom screen and nutritional assessment

Screen all children coming into the healthcare facility for the following symptoms:

- Cough of one week or more or current cough (if HIV positive or history of contact with TB)

- Fever and/or night sweats

- Failure to gain weight and/or loss of weight

- Fatigue/reduced playfulness

Remember, signs and symptoms of TB in children may not be specific as in adults.

In addition to screening for symptoms, you will also want to conduct a nutritional assessment. As you do this, check the following:

- Weight for height

- Height for age, weight for age

- Mid Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC)

CXR (if available)

Conduct a chest x-ray (unless it is unavailable) on all children who have a positive symptom enquiry, and/or are undernourished, and/or have a positive history of contact.

If a chest x-ray is not available and you are working with a child over five years of age who can produce sputum, collect sputum and send the specimen for GeneXpert. Refer children below five to the next level of care for respiratory sample collection.

Xpert MTB/RIF assay

For all children with a positive symptom enquiry, and/or who are undernourished, and/or have a positive history of contact with TB, and an abnormal chest x-ray, collect one sputum(or induced sputum) if the child is able to produce sputum or naso-pharyngeal aspirate(NPA) or a naso-gastric aspirate(NGA) or one stool specimen for GeneXpert testing.

See the resources page for the Standard Operating Procedures for Gastric Lavage/Aspiration; Mantoux and Sputum Induction.

The tuberculin skin test (TST)

The tuberculin skin test (TST) is useful to support a diagnosis of TB in children with suggestive clinical features who have a negative bacteriologic test for TB or who cannot produce sputum. However, a positive TST only indicates that infection with M. tuberculosis occurred and should not be interpreted to imply that TB disease is confirmed. A positive TST in any child is an induration of ≥10 mm irrespective of BCG immunization; however, in HIV-infected children or in a severely malnourished child an induration of ≥5 mm should be considered positive. A positive TST is particularly useful to indicate TB infection when there is no known history of TB exposure on clinical assessment. Remember, a positive TST does not distinguish between TB infection and active disease and a negative TST does not exclude TB disease.

In summary, screening for symptoms, assessing nutrition, taking a contact history, conducting a chest x-ray, and testing with GeneXpert are all important components of diagnosing TB in children. While signs and symptoms of TB in children may not be as specific as in adults, following these procedures will increase the likelihood of catching TB in children early. The following figure walks you through the complete process to take when you have a child client with presumptive TB:

-

Treatment (10 min)

In many ways, tuberculosis in children is treated similarly to tuberculosis in adults. As with adults, the treatment is conducted in two phases—an intensive phase of two months and a continuation phase of four months. Children take the same combination of medications as adults in these phases—2RHZE/4RH. In children with TB meningitis, osteo-articular TB, and miliary TB, the continuation phase is prolonged for 10 months, thus the regimen used is 2RHZE/10RH.

Where treatment differs between adults and children is with the medication dosage. The dose per weight in children is higher than in adults as shown below:

Weight band Recommended Regimen Intensive Phase 2 months of RHZE daily Continuation Phase 4 months of RH daily RHZ (75/50/150) E (100) RH (75/50) 4 - 7 kg 1 1 1 8 - 11 kg 2 2 2 12 - 15 kg 3 3 3 16 - 24 kg 4 4 4 >24 kg Adopt adult dosages During each visit, you will want to weigh the child and adjust the dosage as soon as his or her weigh band changes. Monthly weight should be documented on the TB treatment card and child health card where applicable. Failure to gain weight may indicate poor response to therapy. Children with severe malnutrition should be given medicines at the lower end of the dose range and closely watched for hepatotoxicity.

The recommended dosages for TB medicines in children are:

- Rifampicin: 15 mg/kg/d (10 to 20 mg/kg/day

- Isoniazid: 10 mg/kg/d (10 to 15 mg/kg/day)

- Pryrazinamide: 35 mg/kg/d (30 to 40 mg/kg/day).

- Ethambutol: 20 mg/kg/d (15 mg to 25 mg/kg/d)

When treating a child with TB, make sure to provide his or her caregiver with comprehensive information and education including the reasons why the child must take the full course of treatment even when they begin to feel better. For children less than five years of age, commencement of TB therapy should be documented on the Child Health Card.

Reasons for hospitalization

Children with the following characteristics should be hospitalized

- Severe forms of TB such as TB meningitis (TBM).

- Severe malnutrition that requires nutritional rehabilitation.

- Signs of severe pneumonia such as chest in-drawing.

- Other co-morbidities such as severe anemia. .

- Social or logistic reasons likely to interfere with adherence to anti-TB medicines such as severe alcoholism in a parent or guardian and lack of appropriate social support at the home environment.

- Neonates.

- Severe adverse reactions such as hepatotoxicity.

Pyridoxine supplementation

Severely ill children require hospitalisation and others may require pyridoxine supplementation during treatment. In many children, isoniazid (INH) causes symptomatic functional pyridoxine deficiency, which manifests as peripheral neuropathy. For this reason, the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Program (NTLP) recommends that all children on INH as part of the anti-TB treatment regimen or for TB preventative therapy should receive pyridoxine. The following categories of children are at an increased risk of developing peripheral neuropathy:

- Children who are malnourished.

- Breastfeeding infants

- Adolescents

- Children on high-dose INH therapy (>10 mg/kg/day).

- Children with diabetes mellitus

- Children with renal failure

The following chart describes the proper dosing of pyridoxine for infants, toddlers, and school-ages children:

Age of Child Pyridoxine Dose Infant 6.25 mg ¼ of 25 mg tablet Toddler 12.5 mg ½ of 25 mg tablet School-aged 25 mg 25 mg tablet -

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Key Points (5 min)

- TB infection control (TBIC) measures reduce TB transmission in health-care facilities, congregate settings, and households.

- A plan to prevent transmission of TB in a healthcare facility should be part of the overall facility infection prevention and control (IPC) programme.

- TB infection control has three levels of measures--managerial and administrative controls, environmental (engineering) controls, and personal level (respiratory protection) controls. These measures are organized in a hierarchy with the first level holding the highest priority.

- The spread of TB is worsened by poor living conditions and overcrowding that are likely to exist in congregate settings, making infection control a priority for these settings.

- All household contacts of someone diagnosed with TB should be screened for active TB during contact investigations.

- Two phases are used for treating TB—the intensive phase, which lasts two months, and the continuation phase, which usually lasts four months.

- Because dosage of TB medicines is weight dependent, clients should be weighed at each visit and the dosage should be adjusted accordingly.

- Bacteriologic and clinical monitoring are used for monitoring TB treatment.

- Sputum follow-up should be conducted by microscopy, not Gene-Xpert, at the end of second month, fifth month and end of treatment.

- TB treatment is best given through DOTS to ensure that the client is adhering to their treatment so that they are cured. Clients who are doing well on treatment, motivated to take their treatment, and have no evidence of defaulting treatment may be allowed to be on self-administered treatment (SAT) with periodic reviews in between. This should be done with the client’s interests in mind to ensure the complete their treatment.

- TB has had a significant impact on children causing high rates or mortality and morbidity.

- TB is usually transmitted to children from adult or adolescents in their household.

- Children below 5 years of age are most affected by TB. Infants less than 12 months and children ages 1-5 years of age are more likely than older children to have severe TB and experience rapid onset.

- Key symptoms of TB in children are a cough, which is persistent and not improving on antibiotics; weight loss or failure to gain weight; a fever and/or night sweats; and reduced playfulness and activity and fatigue.

- Screening for symptoms, assessing nutrition, taking a contact history, conducting a chest x-ray, and testing with GeneXpert are all important components of diagnosing TB in children. The Tuberculin Skin Test (TST) is useful to support a diagnosis of TB in children with suggestive clinical features who have a negative bacteriologic test for TB or who cannot produce sputum.

- Children with TB are treated similarly to adults using 2RHZE/4RH, however, the dose per weight in children is higher than in adults.

- In many situations children with TB may require hospitalization and/or pyridoxine supplementation.