Session 9: Tuberculosis and HIV Co-Management

Programmatic Management of Drug-Resistant TB

This session will address TB infection control strategies that can be applied in health facilities, congregate settings, and households. Then we’ll move on to a discussion of how to diagnose, treat, and monitor clients with drug resistant TB.

Learning Objectives

By the end of this session, you will be able to:

- Define drug-resistant tuberculosis (DR-TB) types.

- Describe the epidemiology of DR-TB.

- Describe risk factors and diagnosis for DR-TB.

- Describe care and treatment of clients with DR-TB.

Learning Activities

-

Overview and Epidemiology (10 min)

This section will offer an overview of drug-resistant TB (DR-TB). We’ll look at the epidemiology of drug-resistant TB and risk factors for developing it. Then we will move on to a discussion of how to diagnose, treat, and monitor clients with DR-TB.

Before we can begin, it is important to have a clear understanding of when TB is considered drug-resistant and what the largest forms of DR-TB are. When the bacilli causing the disease are not killed by one or more medicines used to treat it, it is considered DR-TB. Because the bacilli are not killed, DR-TB clients may not get better when receiving the usual TB treatment.

There are several types of DR-TB. Each is based on the number of medicines the bacilli is resistant to. Tap on each to read how they are defined:

Rifampicin-resistant tuberculosis (RR-TB):

The bacilli causing TB disease are resistant to rifampicin, one of the most effective anti-TB medicines, with or without resistance to other medicines.

Isoniazid mono-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB):

The bacilli causing the TB disease are only resistant to isoniazid (INH.)

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB):

The bacilli causing the TB disease is resistant to at least the two most effective anti-TB medicines – isoniazid (INH) and rifampicin (Rif)

Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis (XDR-TB):

This is a more severe form of TB. With XDR-TB, the bacilli causing the TB disease are not only resistant to INH and Rif, but also are resistant to medicines used in treating MDR-TB, namely the fluoroquinolones (ofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, or gatifloxacin) and any one of the second-line injectable agents (kanamycin, amikacin, or capreomycin).

Epidemiology

MDR-TB is more difficult to treat and patients affected usually do not do well on treatment. In 2015, 3.5% of new TB patients and 21% of previously treated patients had MDR-TB globally. This translates to roughly 580,000 people who had MDR-TB. Of these 580,000 people, approximately half of them died. Even though in Sub-Saharan Africa, MDR-TB is more common in PLHIV, HIV-negative individuals also develop it.

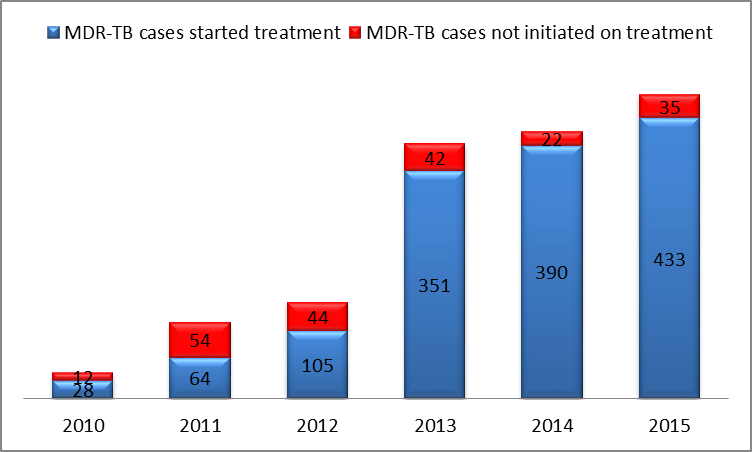

There is a worrying trend of increasing proportion of MDR-TB cases among notified cases. Sadly, in Zimbabwe the number of MDR-TB cases notified has been on the rise since the inception of the programme in 2010. The following chart shows this climb in numbers:

MDR-TB cases diagnosed and initiated on treatment in Zimbabwe from 2010 - 2015

The rise of cases is partially due to the increased transmission within communities and partly due to the increased capacity to diagnose MDR-TB since GeneXpert machines are more widely used. The actual burden of MDR-TB in Zimbabwe is not fully known. In 2015, 468 MDR-TB cases were detected, but unfortunately only 433 (93%) were initiated on appropriate treatment. These missed cases continue transmitting MDR-TB within communities and derail the country’s efforts in meeting the End TB Strategy targets by 2035.

In 2015, 83% of MDR-TB cases in the country were co-infected with HIV. In Zimbabwe MDR-TB is four times more common among people previously treated for TB than new cases (14% vs. 3%). The southern half of the country has a disproportionately higher burden of MDR-TB. This has been closely associated with cross-border migration to other high burden countries in the region.

-

Risk Factors (5 min)

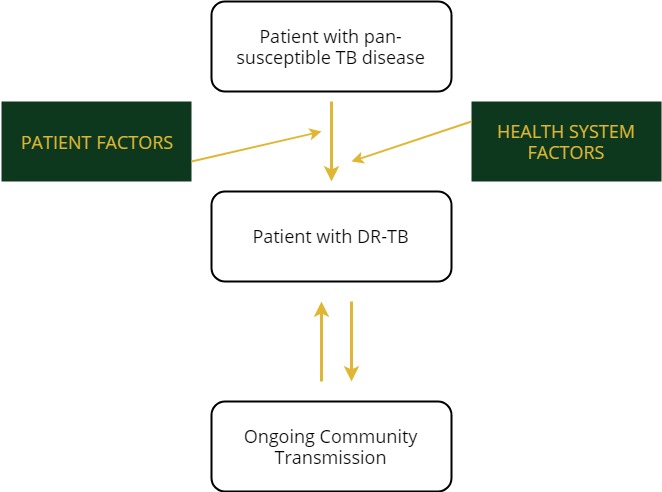

Drug-resistant TB is caused by a number of factors, but is essentially a human caused problem. It’s very commonly seen in clients who have had inadequate or poorly administered drug-sensitive TB treatment. Like with drug-sensitive TB, it can also be transmitted by air droplets from one infected person to another. As such, even patients with no history of TB treatment can be diagnosed with DR-TB.

Some of the other risk factors which may lead to the development DR-TB include:

- Poor selection of drug-sensitive TB treatment regimens.

- Non or poor adherence to drug-sensitive TB treatment.

- Poor monitoring and follow-up of clients with drug-sensitive TB treatment.

- Problems with the quality or supplies of medicines, or both.

- Barriers to treatment such as social, transportation, and poverty barriers.

TB and DR-TB are both spread in the same way and have the same symptoms. Tap on the green boxes to read more about the factors of drug-resistant TB.

Patient Factors

- Poor adherence

- Social barriers

- Adverse events

- Lack of information

- Untreated HIV

- Malabsorption of TB medicines

Health Factors

- Misdiagnosis

- Poor medication quality

- Medication stock-outs

- Delayed diagnosis and treatment

- Improper empiric treatment

- Nosocomial transmission

- Lack of lab reagents

-

Diagnosis of DR-TB (5 min)

The main symptoms of DR-TB are the same symptoms as drug-sensitive TB- cough, fever, weight loss, and night sweats. Clients with DR-TB may have a previous history of DR-TB contact or TB treatment. However, there is an increasing number of new DR-TB cases with no apparent risk factors. The diagnosis of DR-TB relies on obtaining a good history from the client, completing a physical examination, and collecting quality sputum for GeneXpert testing.

A client with symptoms suggestive of DR-TB must submit one spot sputum sample for GeneXpert testing. The GeneXpert test can only report two things-- whether or not someone has TB and whether or not the TB they have is resistant to rifampicin. Diagnosis of drug-resistant TB is based on a GeneXpert result that states, “M.tb detected. Rifampicin resistant.”

-

Care and Treatment (10 min)

Once a diagnosis of DR-TB is made, you or someone in your health facility will need to complete the following steps:

- Notify the district TB and leprosy coordinator (DTLC) and district medical officer (DMO) with a phone call.

- Complete the DR-TB notification form and send it to the district.

- Take a second sputum sample and send it to the reference laboratory for LPA and culture DST.

After these steps are completed, the clinician, in consultation with the district TB committee, will initiate the client on the appropriate second-line treatment. The DTLC will organize contact tracing working closely with the environmental health technician (EHT). Depending on the client’s clinical condition and other socio-economic considerations, the clinician may admit the client or put him or her under ambulatory care.

For treating MDR-TB, there are two regimens that are used—a shorter MDR-TB regimen and an individualised regimen. Tap on each tab to learn more:

Shorter (9 months) MDR-TB Regimen

Clients may be initiated on the shorter regimen if they meet the eligibility requirements and are assessed as being at low risk of having resistance to fluoroquinolones (FQs) and to second-line injectable drugs (SLIDs).

The standard short treatment regimen for MDR-TB treatment in Zimbabwe is:

Intensive phase (4 – 6 months):

kanamycin (Km), moxifloxacin (Mfx), clofazimine (Cfz), pryrazinamide (Z), ethambutol(E), high dose isoniazid (H), and ethionamide (Eto)

Continuation phase (5 months):

moxifloxacin, pryrazinamide, clofazimine, and ethambutol

This treatment is abbreviated as: 4-6 Km, Mfx high dose, Cfz, Z ,E, H high dose, Eto / 5 Mfx ,Z, CFZ , E

Standard (20 months) MDR-TB Regimen

If a shorter treatment regimen is not available or there are contraindications, patients with MDR-TB or other forms of DR-TB may be treated with an individualised regimen designed using the following principles.

- Step 1: Consider use of bedaquiline (BDQ) (or delamanid (DLM) if bedaquiline not available.)

- Step 2: Choose a fluoroquinolone (Group A – Mfx or Lfx). If only ofloxacin resistance from DST is known, Mfx or Lfx (high dose is preferred) can still be added to the regimen, but should not be counted as one of the effective drugs. Treatment with a later generation FQ (Mfx or Lfx) significantly improves RR-TB or MDR-TB treatment outcomes; they should therefore always be included unless there is an absolute contra-indication for their use.

- Step 3: Choose an injectable (Group B – Km, Cm, Am.) If clinical history or DST suggests resistance to all SLID, or in case of a serious adverse event (hearing loss, nephrotoxicity), the injectable should not be used or should be promptly discontinued. In children with mild forms of DR-TB disease, the harms associated with an injectable may outweigh potential benefits and therefore injectable agents may be excluded in this group.

- Step 4: Choose at least two Group C drugs (Lzd, Cfz, Eto, Cs) thought to be effective as additional core second line drugs to BDQ/DLM, FQs, and SLID. If efficacy is uncertain, the drug can be added to the regimen, but should not be counted as an effective drug.

- Step 5: Choose D1 drugs (PZA, INHhd, EMB) as add-on agents. PZA is routinely added to most regimens. High dose INH may further strengthen the regimen if DST shows INH sensitivity, or INH resistance is unknown. D1 drugs are usually added to the core second-line drugs, unless the risks from confirmed resistance, pill burden, intolerance or drug-drug interaction outweigh potential benefits.

- Step 6: Only choose D3 drugs if there are no other treatment options available due to highly resistant forms of DR-TB or multiple intolerances to other DR-TB drugs.

The final individualized DR-TB regimen will consist of at least 5 drugs with confirmed or high likelihood of susceptibility from the following list: Bdq or Dlm, Lfx or Mfx, Km (Am, Cm), Eto, Lzd, Cfz, Cs, Z, INHhd, E.

Standard XDR-TB regimen

The standard regimen for XDR TB for Zimbabwe is 6 months (Cm-LZD-BDQ-Lfx-Cfz-Amx/clv- Hhd) plus 12 months (LZD-BDQ-Lfx-Cfz-Amx/clv-Hhd).

Patients who are considered to be at high risk of XDR TB and are diagnosed of TB should be treated for TB using this empiric regimen that most closely matches the susceptibility pattern. This includes patients previously treated for MDR TB and contacts to XDR TB cases.

If medicines in this regimen have been used in a previous failed regimen, substitution may be made with a different medicine within the same group that is likely to be effective (for example, replacing levofloxacin with moxifloxacin).

Isoniazid Mono-Resistant Regimen

Patients with isoniazid mono-resistance continue on four drugs up to the end of the treatment. Hence for pulmonary tuberculosis the treatment regimen shall be 6 months HRZE.

-

Monitoring of MDR-TB Patients (5 min)

Clients with MDR-TB should be closely monitored for potential adverse events and sputum conversion.

All patients with DR-TB need systematic clinical and laboratory monitoring as specified in the monitoring schedule in the clinical guidelines before and while on treatment with comprehensive management and reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions. This is referred to as active Drug Safety Monitoring (aDSM.)

Steps to take when monitoring the client will differ depending on whether he or she is in the intensive phase of treatment or the continuation phase. Tap on each tab to read more.

Intensive phase monitoring

Sputum should be collected monthly and sent to the reference laboratory for culture and DST. The decision to switch from the intensive phase is based on the patient having at least four consecutive culture-negative sputum results.

Continuation phase monitoring

Sputum should be collected once every two months and sent to the reference laboratory for culture and DST. For a client to be declared cured, he or she needs to complete treatment and have at least three documented consecutive culture-negative results.

All DR-TB patients should have, as the minimum baseline investigations and an estimated creatinine clearance, audiometry, vision tests, thyroid stimulating hormone, liver function tests, urea and electrolytes and ECG. These tests should be repeated as indicated in the schedule for monitoring of DR-TB patients.

For more information on patient monitoring, refer to the Clinical Management of Drug-Resistant Tuberculosis treatment guidelines in the resources section on this training.

-

Knowledge Check (5 min)

-

Key Points (5 min)

- Clients with MDR-TB present like those with drug-sensitive TB.

- Early diagnosis and prompt initiation on treatment for all those diagnosed is important to curb the spread of DR-TB.

- After diagnosis with GeneXpert, sputum are collected for LPA and culture + DST to make a decision on the appropriate treatment regimen.

- It’s important to monitor MDR-TB patients for adverse events and for clinical and bacteriological treatment response.

- Healthcare workers should maintain good TB infection control practices when caring for patients with MDR-TB.