Bodies and Structures 2.0 is an innovative digital platform that offers tools for researching and teaching spatial histories of modern East Asia. The site has 17 individually authored modules and is directed by David R. Ambaras and Kate McDonald. In this interview, they discuss digital history, the development of the platform, and how it encourages users to think differently about space, place, and crafting historical narratives. They were interviewed for JJS by Erin Trumble, a PhD candidate in the Department of History at the University of California Santa Barbara.

How did you come up with the idea of Bodies and Structures? What did some of the first drafts of the project look like?

David Ambaras It started with a chance encounter at the Association for Asian Studies annual conference in 2016. Kate was on a panel presenting something on Manchuria and I was in the audience. We had never met, but we both had interests in questions of space and spatial history and I knew of her dissertation. After the panel session, I spoke with her and we realized that we should probably talk more. Kate came to North Carolina for a couple days, and we did a reading group and a workshop. And then we thought, “what can we do in terms of a project?”

Our first idea was to do a digital reader of primary sources on the Japanese empire with annotations and various maps and other things that might go with it. In fact—just to put in a plug for it—Sayaka Chatani at National University of Singapore has a website right now that does a lot of that, and it’s terrific. We thought about that and about people who we might want to participate. Then we did a workshop or a miniconference a few months later, and we started thinking about what medium and what kind of tools would be best for this.

We were moving away from curating a primary source reader toward building on research in the spatial humanities to present research from the field of Japanese history in interesting ways. I had been playing around with Prezi and did a presentation using Prezi that became the basis for my module in Bodies and Structures. It allowed me to show how documents were moving, how people were moving across this space that was two dimensional, but deep as well. We thought we’d go with Prezi. Then Prezi changed its entire approach and became just a glorified PowerPoint, so we abandoned that. But we had a bunch of people who were interested in working with us and we wondered, “what can we do?” We found Scalar—I think each of us found it on our own, along with Noriko Aso. After looking at it, we thought it would allow us to develop what we wanted to do, at least preliminarily. It wound up being something we were able to use ourselves, and we were then able to contribute to developing Scalar.

Kate McDonald The thing I will add to the story is the idea of an annotated primary source collection, with important documents for thinking about the spatial history of Japan and the Japanese empire, started to feel unsatisfying. In a reading group at North Carolina State University, we read Tim Cresswell, Doreen Massey, and other incredible, foundational thinkers in the spatial humanities. We were taken with Massey’s notion of space as “the simultaneity of stories so far” and the potential to think about these documents, historical events, people, as being parts of lots of different places, constituted in different spaces.

If we put these materials in a printed volume, we could tell people about this notion of the simultaneity of stories so far, but we couldn’t show them. If we used a digital format, we thought—and this was maybe our naivete at the early stages of doing digital humanities— “well, we can build something, we can make everything infinitely recombinable, we can have a map where things are farther away in the winter than they are in the summer because of the snow, and it takes longer to walk places.” Amy Stanley was also part of working with us early on, and she talked about how the weather affected distance a lot with her story of Tsuneno (Stranger in the Shogun’s City: A Japanese Woman and Her World [Simon & Schuster, 2021]).

D.A. If you look at Maren Ehlers’s module, you’ll see exactly that.

K.M. We wanted to move away from telling and to do more showing. That’s why we ultimately chose Scalar. It was designed to do that very thing. Then we pushed the envelope as far as we possibly could with it.

What were some of the roadblocks you encountered, either in formulating your ideas for the website or implementing those ideas? How did you work past those roadblocks?

K.M. The first roadblock was realizing we couldn’t build something from the ground up. Both money-wise and in terms of our own capacities, we weren’t going to succeed going that route. The question became “how do we match our vision with the platforms that are available?” The really good news on that front was that Scalar was an incredible platform; we could ask the development team questions like, “Can we do this? Can we do that?” And they would say, “sure, you just have to do it this way, or no, that’s not possible.” Through those conversations, we were able to align our vision with the realities of the platform itself, and then also get some ideas for what might be interesting to do with the platform to develop it in the future.

D.A. Scalar said, “if you get a grant, we’ll be glad to work with you on this.” With the NEH Digital Humanities grant, we were able to contract with Scalar to improve some of the things that we all recognized could be improved and also to develop new tools for Scalar.

Can I ask a little bit more about what things you immediately thought needed to be improved and what tools you developed?

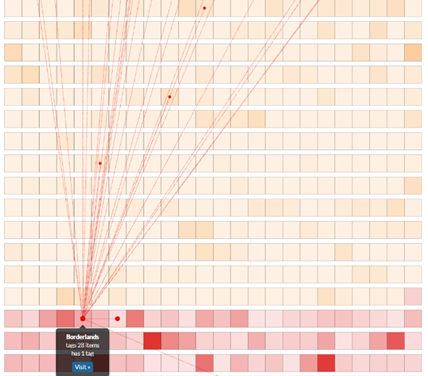

D.A. One of the things that appealed to us about Scalar—both what was available in Scalar at the time and the idea behind Scalar—was that every page can be combined with other pages, whether text or image or sound or whatever. We really wanted to develop those connections as much as possible. That required making sure that tagging could be visualized at multiple levels of tags and that the Google map tool could express some of the multivocality we were describing or trying to describe in our project. You wouldn’t just pull up a pin and there’d be one thing there, but you’d pull up a pin and there would be multiple things. And you might even be able to see how that pin relates to other pins and pathways that the various authors created. That required some doing.

We were also intent on making this project as participatory as possible. In the making of Bodies and Structures—both 1.0 and 2.0—it wasn’t simply Kate and me soliciting contributions from people and then working them up into something. It was an iterative process of people presenting and commenting on each other’s stuff and then commenting on the meta framework. What are the concepts that cross these different modules? How can we develop the relationships in interesting ways using tags, but also linking from page to page, from a page in module 1 to a page in module 2? And so forth.

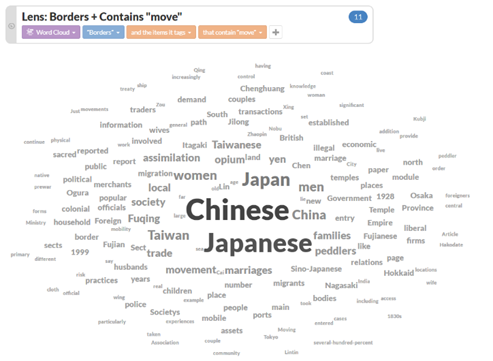

It was participatory within the group. We also really wanted a way in which it would be participatory for anybody who came to the site. You wouldn’t simply go to the site and read it, but you could make use of it—if you were not a member of the Bodies and Structures collaborative, you could nonetheless make use of the site to build your own collection of pages or build a pathway that you saw as salient and so forth. That required enhancing the search tools and the visualization tools. We asked the development team at Scalar about that and through our conversations we came up with this idea of “Lenses,” which ended up being a big part of the NEH grant.

K.M. We worked with Erik Loyer and Craig Dietrich and another developer they had subcontracted. The five of us met every other week for a year, much of it in Year 1 of the pandemic. Over Zoom we would see the mock-ups and we would talk about how to develop them. This experience was so cool because it was such a conversation. We also organized a series of “builders’ workshops” for our module contributors. All three workshops for 2.0 ended up being virtual. Four or five different time zones were represented. But we managed to stay very collaborative. We would get on Zoom and break up into small groups. Then the groups would meet on their own to figure out how best to put together their modules and what the site as a whole should be doing. It was fun and so different from the model of writing by yourself and trying to convince people that your ideas are right. You had people who were already cheering you on and trying to get to the best possible version of the materials we had.

That’s a great segue to my next questions. How does Bodies and Structures encourage its users to engage with the concepts of space and place in new ways? What insights does it offer that traditionally published works aren’t as capable of provoking?

K.M. One of the things we’re doing in Bodies and Structures, and what the modules as a group are doing, is saying that space is important. The spatial humanities as a field is not that old. People have been thinking about space and things like cartography for quite some time in the discipline of history. But only recently have we been really putting space front and center as both an element of how our historical actors encountered the world and as a concept that we as historians and as geographers, and as people working in literature, anthropology, and other fields, also need to be conscious of. We need to be conscious of the ways we’re using space, the spaces we’re embedded in, and then also attend to what our actors are doing with space.

The need to think about space as both a category of historical experience and an essential concept for historical thinking was one idea we really wanted to put on the map, as it were, and I think that we did that. At the same time, because we were reading deeply in the spatial humanities, we didn’t want to replace one set of fixed spatial categories—the nation-state or the region or whatever—with another one. That wasn’t the solution. “Yours is wrong, but ours is right”—no. The point is that spatiality is very dynamic. Depending on who you are in the world, you encounter spatial structures differently, the spatial structure looks different, it has different effects. Or, it may not appear to you at all, for example. So, we wanted to really bring that sense of fluidity and indeterminacy to the study of space and the history—originally of modern Japan and the Japanese empire—but now modern East Asia.

D.A. Another thing we contribute is just asking people to get lost in the site. This ties in with what Kate has been saying. We’re constantly orienting ourselves. We forget that people are always orienting themselves, that we as scholars—when we go to a new archive, for example, or a library, or wherever it is, or a field site—have to orient ourselves. And it can be very disorienting. We wanted to build that disorienting potential and the potential for exciting juxtapositions and new understandings and insights into the site itself. The fact that there are all these pages—I think we have 1,500 pages of text and navigation and roughly 1,000 media objects that people can find their way through—if you want, you can go in a linear way through a module, although you’ll still get sidetracked. Or you can jump into various places and hit a tag and see what’s there and go someplace else.

Some of the feedback on earlier versions of the site suggested that it was too disorienting. We’ve tried to make it as user friendly as possible. But we also want people to embrace the disorienting quality of it, because we think it’s important for thinking about how humans are spatial. There are certain things that we do unconsciously, but there are certain ways we have to figure out what’s going on. And that applies to our historical subjects and to us as historians and people.

How can the nonlinearity of Bodies and Structures help people imagine history differently?

D.A. First of all, it helps us to get beyond the kind of traditional understanding of what a historian is supposed to do.

K.M. I’ve never figured out what historians are supposed to do.

D.A. Right? Except we’re supposed to write linearly. We’re supposed to write in kind of a narrative argument. Everybody who goes through this process will tell you that really interesting stuff gets left behind when you do that. One view of that is, “well, of course, it gets left behind, you have to make choices in order to construct this argument.” But another view is there’s so much going on at the same time—going back to Doreen Massey—that is important. And that should be kept in view; we shouldn’t lose track of that. Moving beyond that kind of straight linear approach to a nonlinear approach to writing I think is good, not only as a writing practice but also because it helps us understand how people might have perceived their own existence in time and space. They weren’t always on a path toward this one thing. There’s lots going on at the same time, at different scales, at different levels, in different networks and relationships. Our project helps people to constantly be aware of that and think about how they might represent that.

K.M. There’s so much more history out there than I think you’re really conscious of when you start to think spatially and at the level of encounters, of things having meaning on different scales. Nobody wants to read a book that has everything in it. That would be a difficult read. But as a thinking practice it’s something we should be doing. It raises questions about what stories are important to tell. It’s totally possible to write histories in different time-spaces using traditional print media—for example, Anne Walthall’s book about Matsuo Taseko, Weak Body of a Useless Woman [(University of Chicago Press, 1998)]. One of the things that’s so wonderful about her book is that the narrative and the argument are driven by the time scale of this woman’s life. It’s not all leading up to the climax of the Meiji Restoration. It’s just operating in a different spatiality and a different temporality. As a discipline, it’s very rare to find these types of books, and even rarer to find them done as well as Anne Walthall does it. One of the things we’re doing with Bodies and Structures is showing that we could be writing histories in different spatialities. We could be doing more of that, and it can be really, really interesting.

D.A. The digital platform gives us the tools to do that. And it should give us the confidence to tell publishers, “you need to rethink how you publish scholarship, because there is so much potential to do things beyond the standard monograph.” That doesn’t mean you abandon the argument. It doesn’t mean you abandon narrative. But it complicates things. The tools are there. I don’t know the market dynamics, I don’t know what the economics are, obviously.

K.M. I assume they’re bad.

D.A. Yeah, they must be bad, because no publisher wants to do it, right? But as writers, as historians, as storytellers, we have these different possibilities now, and we shouldn’t sacrifice them simply because there is an existing model for how one does history. Or how one publishes history.

K.M. Or how one makes knowledge in history.

From my understanding, one of the ways you make knowledge with Bodies and Structures is through deep mapping and thick mapping. Can you explain what these two approaches are and why it was important to you to use both of them?

D.A. I’m less and less convinced of the differences. I think the premise of deep mapping is that there’s a place that gathers things. It’s this phenomenological approach, that there’s a place that is produced through various movements and that it gathers things: it gathers memories, it gathers events, it gathers meteorological information, it gathers all kinds of stuff. Deep mapping is basically trying to add as much stratification to that place as possible to tell the various stories that are happening in that way. Thick mapping starts from the premise that we make all kinds of connections; these connections are constantly in flux, and they’re rhizomatic, things attached to other things, they sprout up here, they sprout up there, and we should try and trace out connections.

Basically, place is produced through connections across space. Deep and thick mapping are really interrelated. I don’t think you can do deep mapping without thick mapping. And I don’t think you can do thick mapping without deep mapping; you have to have these two things going at the same time. I worry less about the distinction between the two and more about just the sense that we’re trying to be rhizomatic and trying to show the different combinations of things that are in play.

K.M. The idea is that stuff doesn’t happen in a place. The stuff that’s happening makes the place. So you want to have a way of mapping and of talking about and conceiving of place that doesn’t get stuck in structural models. For example: “This place is a periphery.” Sure, we can use a core-periphery structure, if we want to talk about one element of it, but this does not define the place, actually. So let’s go deeper: what else is happening here? Those events, those people, those rhythms, what are they connected to? And how did those connections make this place something very different from what you expected when you were thinking about it in core-periphery space? You can have this very dynamic unfolding and constant upsetting of what or even where you think this place is as you go deeper into it. When we encountered deep mapping for the first time, we were in conversation with the work of John Corrigan, David Bodenhamer, and Trevor Harris, who have a couple volumes on this on this topic. John Corrigan has really supported the project for a number of years.

We’re currently on Bodies and Structures 2.0. What were some of the major changes you made between Bodies and Structures 1.0 and 2.0? And why was making those changes important?

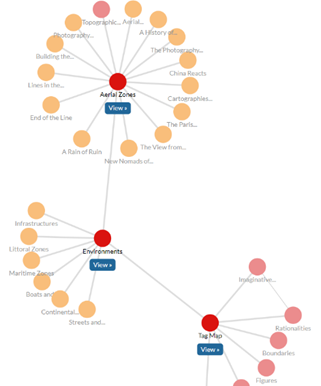

D.A. In terms of content, 1.0 had seven modules in total, and 2.0 has 17. We added a lot of material, but it still doesn’t cover everything that should be there. But we got a lot more coverage. We got stuff from outside the discipline of history as well. We included art history and literature. We moved into Southeast Asia a bit with Michitake Aso on Vietnam. Another part of the transition from 1.0 to 2.0 was the tools we’ve talked about previously: enhancing the visualizations, the search capabilities, building Lenses. Those were the two main shifts from 1.0 to 2.0. We also redid the tag map. In 1.0 we had two broad categories in place and spatiality. And then we had a bunch of what we call crossings, which were these kinds of general top-level tags, you might say.

That worked for 1.0. But over the course of developing 2.0, during meetings among the different collaborators, we started to think more carefully about more precise ways we could tag things to make conversations viable. We reconceptualized all of that. That was a big change as well.

K.M. The tag-map change was intentional. One of the points we want to make with the multiple editions of the site is that our conceptual maps are defined by the things we’re reading and the people we’re in conversation with. So when you add 10 new people, writing about 10 new things, that conversation should change. Your conceptual map of the field that is Bodies and Structures should look different. We spent a lot of time as a group figuring out what that new conversation was, which was also super fun.

What are some of the pedagogical benefits of using Bodies and Structures in the classroom?

D.A. There can be a number of benefits. It contains a lot of primary sources in translation, but a lot of them are also annotated or linked to images or other context-giving content. Using Bodies and Structures is a way to expose people to the kinds of primary sources they wouldn’t find in a traditional reader or in a textbook. At that level, it gives instructors a lot of pedagogical resources. It also gives college students different kinds of content to work with in terms of subject matter and in terms of thinking about connections, simultaneities, or temporal discontinuities in space, when they can juxtapose to two different modules. For students who are thinking, “what can I do with digital work?” or for instructors who say, “how can I help students to get their feet wet in digital work?” we offer a model for things you can do.

K.M. One of the things we’re showing is that the writing should look different. The way you build a narrative is different in a digital space. It should be different. We’re not just publishing words in a new medium; how we approach writing itself is very different. This was something that all of our module builders encountered. They thought they knew how to write the story they wanted to tell. As they got into putting it into Scalar, they had to really rethink, sometimes several times: how are you going to link things across multiple pages? How are you going to take advantage of being able to be in conversation—really explicit, visible conversation—with other modules, with other parts of your own story? So at the level of digital storytelling—and in fact, Bodies and Structures has been used as an example of excellent digital storytelling—it’s a good model. Another way that I think Bodies and Structures is really useful and interesting is that the tag map visualizes a thing that, as professional historians, we usually keep in our heads. It’s so hard to communicate conceptual maps to graduate students who are in coursework and to undergraduates who are trying to get a sense of a field to do a thesis or a significant research paper. But now I can actually show somebody. When I’m talking about a conceptual map of the field, here is what I mean. We have groups of works and they are conversations. Some of the topics and books appear in multiple conversations. It’s right there. Showing people how historians think is a valuable contribution.

What advice would you give to people who are interested in utilizing digital history but who are unfamiliar with it as a genre?

K.M. I would suggest that you start by asking, “what would be the best possible structure to tell the story that I want to tell?” Think big. I have a little folder that’s a bit of an archive of the project. I’m hoping that somewhere in there are the drawings I did with my kids’ colored pencils about how the tag map should look. We had some draft modules where we had to untangle the way the threads were working. We just doodled them out over and over again until we had a flow that made sense, and the linkages between the different strands were sensible also. Start with questions like, “if this could be anything, what would it be? And why would it be that way? What’s the point that you’re trying to make by telling the story this way versus another way?” Once you’ve got that figured out, you can figure out what platforms or various technologies are available for realizing your vision. Does it need to be digital? Could you just have a very, very beautiful printed map? Maybe for what you’re talking about, you can do it on paper and save yourself a bazillion hours and still have the same outcome.

I would start there. Then I would be prepared to be patient with yourself and the process. Get a lot of feedback from people. We did that. Many different versions of feedback. Some of it in formal ways, like peer review, but also in other informal ways, such as asking people to take a look at the site and give us their unvarnished thoughts about it. You also have to be willing to make people a little bit mad. As David said, Bodies and Structures is disorienting at times. We went through a lot of back and forth to find an appropriate level of disorientation. The goal was never perfect orientation. Our goal was to find the perfect balance: just enough disorientation that it gets you out of your rote mind and into an explorer mind but not so much that you get frustrated and walk away. I don’t know if we’ve achieved that, but that was our goal.

D.A. And that’s disorientation on your authorial side, as well as on the side of the recipient. Because you have to think through how you see yourself putting something together and whether it really ultimately makes sense. I would add to what Kate said at the beginning: listen for the voices that you want to represent. What voices are there? And how do you think the conversation or the disparity among those voices can best be represented? I’m thinking of our friend Martin Dusinberre’s work. In his most recent book (Mooring the Global Archive: A Japanese Ship and Its Migrant Histories [Cambridge University Press, 2023]), he includes a statement by a Japanese woman, a karayuki-san, one of many who migrated to the colonial Asia Pacific to engage in sex work. She wound up in Thursday Island in Australia, and she was interrogated by Japanese elites, on behalf, I think, of the Australian government there. Martin teases out from that statement the different voices, the different experiences, the different histories, the different intentions that are not apparent, necessarily, in that letter. He brings them out, and he does it in print.

Maybe that’s how you want to do it. You want to stay with the print version. But it may be that you can take the statement and put it on a page and then begin to tease out the different voices and layers through associating other media objects with it, through having call-out notes that raise questions about something or that interject yourself as a voice into this. Scalar allows one to do that. Other tools do that as well. And one can probably build tools to do that too. But always think about “what are the voices that you want to see represented?” And then “what are the best ways of doing that?” There’s also a certain trend that suggests that to be digital, it has to be Big Data. If you’re not doing Big Data work, then what are you really doing? I think a lot of people in digital humanities would push back against that, but digital humanities is multiple. We consider ourselves to be Small Data historians, reading our documents and other sources closely.

There are so many different ways to do digital history. You shouldn’t think, “oh, digital history has to be this or digital humanities has to be that.” Just figure out what it is that you want to represent and then figure out the best medium for it. There may be good off-the-rack tools. We were so fortunate to find an off-the-rack tool that allowed us to do this. You don’t have to invest in building something from scratch; see what you can do with what’s available. And then if you really need something more bespoke, you can figure out how to go about doing that. There are lots of ways to get started.

David R. Ambaras is a professor of history at North Carolina State University. He has published Bad Youth: Juvenile Delinquency and the Politics of Everyday Life in Japan (University of California Press, 2006) and Japan’s Imperial Underworlds: Intimate Encounters at the Borders of Empire (Cambridge University Press, 2018). He is currently working on the project “Maritime Connections and Japanese World-making, 1950s–1960s.” Kate McDonald is an associate professor of history at the University of California, Santa Barbara. She has published Placing Empire: Travel and the Social Imagination in Imperial Japan (University of California Press, 2017) and is currently working on the project “The Rickshaw and the Railroad: Human-Powered Transport in the Age of the Machine.” Together they direct Bodies and Structures: Deep-mapping Modern East Asian History. In 2019 they received the NEH Digital Humanities Advancement Grant that allowed them to improve and expand the site.

Erin Trumble, a PhD student in the Department of History at the University of California Santa Barbara, studies gender in early modern Japan, paying particular attention to the construction of femininities. Her past work focused on fighting women, how they were portrayed in woodblock prints and literature, and how they participated in the Boshin War of 1868–69. Her current project involves looking at how intersections between age and gender affected identity making for retired women in the Edo period.

This interview was made possible by financial support from the Japan Foundation, New York.