Traditional definitions of data literacy have been centered around developing skills for reading, writing and utilizing data in different ways. However this approach may fall short of harnessing data’s full potential, as within this paradigm, learners are rarely taught to question what data is used for or how it is shaping society. It also often excludes aspects of power, equity, empowerment, and emancipation. These additional dimensions of learning about data have been often labeled as “critical data literacy.” In our new paper, Sayamindu Dasgupta and I attempt to provide a review of recent and current K-12 and undergraduate design approaches and strategies used in prior empirical work on critical data literacy.

Our foundational approaches are derived from combining theories of critical pedagogy with constructionism to foster critical data literacy. We take this approach because we see constructionist principles as creating space for critical perspectives in learning experiences without displacing the focus on developing other data literacies. Additionally, because constructionism offers learners support for multiple pathways of learning, novices and learners who self-identify as “non-technical” can greatly benefit from it. For example, in our review, we found approaches using arts-based representational techniques and media to enable learners to critically engage with data. This method is not only appealing to a diverse group of learners but also allows for a broad variety of creative outcomes.

During the process of selecting papers for our study, we encountered varying perspectives on what defines a constructionist activity. While some scholars emphasize the importance of minimally guided discovery, others argue that some guidance is needed and that constructionism is all about the learner constructing their own understanding through hands-on exploration. To address this, we defined constructionist learning experiences as those that include (i) student centered discovery, (ii) a learning environment rooted in meaningful contexts, (iii) peer feedback, reflection, and iterative refinement, and (iii) envisioning a better world through technology fluency and interpretation. Another aspect we had to consider during our review was whether a physical artifact was necessary for an activity to be considered constructionist. For example, if students are learning about plant growth at the population level and evaluating data, is it a constructionist project? For our purposes, we decided to include a project if it supported learners’ conceptual understanding without requiring a physical artifact to be constructed and included papers that enabled connection to data, critical reflection with data, and meaning-making work with data.

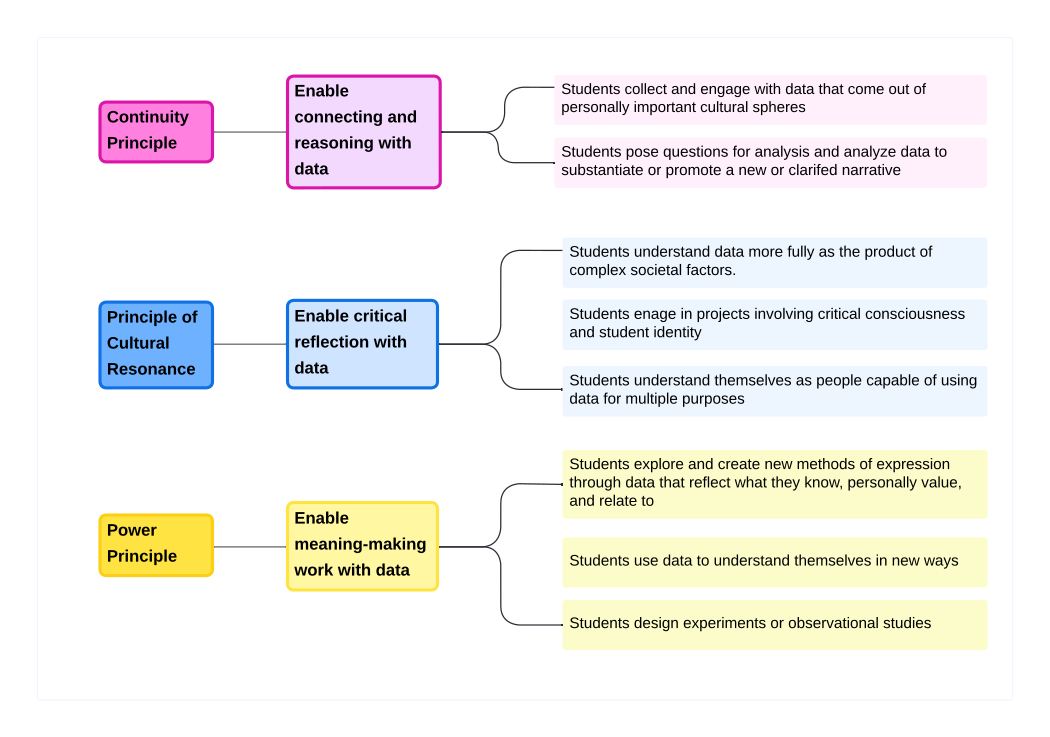

By carefully considering these perspectives and definitions, we aimed to establish a clear framework for identifying constructionist activities in the context of critical data literacy. Our framework highlights the three key constructionist principles as articulated in Mindstorms by Seymour Papert: the continuity principle, the principle of cultural resonance, and the power principle. The figure below visualizes the hierarchy showing how the three constructionist principles relate to the papers that we analyzed for this study.

A hierarchy showing how the constructionist principles relate to the papers analyzed for this study

The continuity principle within critical data literacy connects learning to “well-established personal knowledge” through which the participants can inherit “warmth, value, and cognitive competence”. As part of this principle, learners learn to critically reflect with data by taking an active role in collecting, analyzing and investigating data that are personally meaningful to them. For example, in Clegg et al.’s study, Division I student-athletes’ collected and analyzed their personal data to inform their practice, play, and even daily habits (e.g., sleep, screen time). The continuity principle emerges in this study in two ways. Firstly, by having the students collect and analyze their own personal data, students had to consider the methodologies used as well as the level of detail in the collection process. Understanding that data collection methodologies are designed to highlight some aspects and not others is an important aspect of critically reflecting on data’s origins, as it helps students gain an understanding of the problematic non-neutral aspect of data. Secondly, by interpreting the collected data as a metric of their performance, it helped students establish the notion that data was already a part of their lives. Thus, when students merge their learning environment with their surrounding reality, they can understand that knowledge is “situated” and cannot be detached from the contexts in which it is created or realized.

The principle of cultural resonance highlights the significance of considering the social context in which data is collected and exists. Students are encouraged to critically reflect on the data they receive, and to consider how it aligns with their own identity and beliefs. Enyedy et al.'s study of urban students using GIS maps to study their own communities and demographic trends exemplifies this principle. For example, the study showed that learners may not always feel that the data lent insight or argumentative power to what they already knew and experienced about past and current inequities. Therefore, it is important to politicize the use of data, and look at it not only from the perspective of a passive user but also in the context of someone who can critique the hidden aspects of data. Incorporating students’ lived experiences into classroom projects, as Enyedy et al. demonstrate, can help students better grasp the political and complex nature of data.

Lastly, the power principle emphasizes the active engagement of students in making meaning with data. This principle encourages students to situate their encounters with the world in appropriate cultural contexts, fostering a deeper understanding of their lived experiences and values. In the literature reviewed, the use of wearable technologies such as fitness trackers was employed as a valuable tool for illustrating how learners are situated within their cultural contexts. For example, as part of the elementary statistics classroom unit, Lee et al. integrated wearable activity trackers for students to compare favored recess activities to determine which were more physically demanding. Additionally, Philip et al. also highlight the importance of peer-generated data from mobile technologies as a valuable learning tool for students. This type of data-driven learning encourages students to better understand the complexities of their own cultural identity in relation to that of others and can help learners develop an appreciation for the diversity that exists within their communities. In addition to self tracking devices, log data is also being used to help students engage in self reflection about themselves and their broader community. Scratch Community Blocks is another attempt to support such reflection. Through these blocks, youth are able to query data about the Scratch user community, such as how popular a particular user is, or which programming blocks are most used. Thus, by critiquing, questioning, and debating the implications of social data analytics, students have gained a sense of critical data literacy through these experiences.

In summary, these principles intertwine to form a comprehensive approach to teaching critical data literacy. Taking this into consideration, designers of learning environments that integrate constructionism with critical data science education should carefully consider if and how the three principles, viz., continuity principle, power principle, and the principle of cultural resonance are realized in the technical and pedagogical design. In addition, the insights gained from this study have revealed several trends as well as opportunities for further research that can be used to inform the design of future learning environments.

Of course, our work is not without important limitations. We acknowledge that the selection of papers reviewed may be subject to bias and may have limited the inclusivity of the corpus and the resulting findings. Furthermore, since what constitutes a constructionist activity is an open question, our determination of constructionist learning approaches may not cover the whole breadth of constructionism. We discuss these caveats, as well as our methods, theoretical background and findings of this study in detail in our paper which is now available for download as an open-access publication from the ACM digital library.