Back to Cities and Architecture

Click on thumbnails to enlarge them

Almaliq

The Ili River valley is one of the historic centers of human settlement in Inner Asia. Tucked in between east-west ridges of the northern Tienshan Mountains, the valley offers both pasture and fertile agricultural land. While access to it from the east requires descending a precipitous pass, the valley opens to the west, as its main river flows into today’s Kazakhstan in the region known as Semirech’ie (the Seven Rivers). Given its favorable location and natural conditions, the Ili naturally was a focus of contention by those who wished to control central areas of Inner Asia. The visitor today to the Ili region can see the tumuli of burials of the Wusun, an important nomadic confederation that figures in the Chinese sources at the very beginnings of the Silk Road in the second century BCE. On the modern end of the chronological scale, one can see in the now chief city in the region, Yining (Kulja), the buildings of the once impressive Russian Consulate, which became an important outpost in the “Great Game” of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. As one heads from Yining toward the modern border with Kazakhstan, one comes to the now inconsequential town of Almaliq, which was prominent during the period of Mongol rule in Central Asia.

One of the earliest accounts of Almaliq is that by the Daoist monk Ch’ang-Ch’un, who passed through the town in early autumn 1221. He reported that there was a local Muslim ruler (from the Turkic Qarluk tribe) and a resident Mongol official. One of the successors in the local dynasty would cement his position by marrying a granddaughter of Chingis Khan. Under Ögedei, Chingis Khan’s successor, even though the local dynasty was left in place, direct administration and tax collection in Almaliq and other regions further to the West was placed under the Khwarezmian Mahmud Yalavach. With the consolidation of the division of the empire into the separate uluses that had been assigned to Chingis’s sons, Almaliq went from hosting a summer hunting camp to become the capital of his son Chaghatay and his heirs, The famous chronicler of the early Mongol Empire, Ata-malik Juvayni, stayed in Almaliq in 1253 and on one or two other occasions while on administrative assignment.

There is ample evidence about the flourishing of the local economy, starting with Ch’ang-Ch’un’s account:

They gave us lodging in a fruit-garden to the west. The natives call fruit a-li-ma [i.e., apple], and it is from the abundance of its fruits that the town derives its name. It is here that they make the fluff called tu-lu-ma [=cotton] which gave rise to the popular story about a material made from ‘sheep’s wool planted in the ground.’ We now procured seven pieces of it to make into winter clothes. In appearance and texture it is like Chinese willow-down—very fine and clean. Out of it they make thread, ropes, cloth and wadding.

The farmers irrigate their fields with canals; but the only method employed by the people of these parts for drawing water is to dip a pitcher and carry it on the head...Every day the people brought us an increasing number of presents.

We know from other sources that Almaliq was for a time “a great commercial city” on one of the main roads to China. Mention of it appears in Western accounts, and it became important enough so that a Roman Catholic bishop and probably a Nestorian metropolitan were appointed there. However, in 1339, a number of Franciscan monks were murdered there, an event probably connected with the succession of a Muslim ruler in place of a pagan predecessor on the local throne. In fact, Ch’ang-Ch’un notwithstanding, it seems that Islam was slow to take hold in the region. The ruler given much of the credit for its ultimate success in the Chaghatayid dominions was Tughluq Temür (r. ca. 1351-1363), whose tomb in Almaliq is the main reason to visit the town today.

We know from other sources that Almaliq was for a time “a great commercial city” on one of the main roads to China. Mention of it appears in Western accounts, and it became important enough so that a Roman Catholic bishop and probably a Nestorian metropolitan were appointed there. However, in 1339, a number of Franciscan monks were murdered there, an event probably connected with the succession of a Muslim ruler in place of a pagan predecessor on the local throne. In fact, Ch’ang-Ch’un notwithstanding, it seems that Islam was slow to take hold in the region. The ruler given much of the credit for its ultimate success in the Chaghatayid dominions was Tughluq Temür (r. ca. 1351-1363), whose tomb in Almaliq is the main reason to visit the town today.

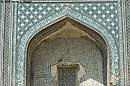

In his “History of the Moghuls” the 16th-century author Mirza Muhammad Haidar devotes a number of pages to Tughluq Temür’s conversion, which he connects with the activity of local Sufi orders. While by Haidar’s time Almaliq had fallen into decay due to all the local wars, he took particular note of the location there of Tughluq Temür’s tomb

with other traces of the city’s prosperity. The dome of the Khan’s tomb is remarkable, being lofty and decorated; while on the plaster, inscriptions are written. I recall one half of a line, from one of the books, namely: ‘This court was the work of a master-weaver’ [shar-baf]—words which show that this master was an Iraqi, for in Iraq they call a weaver ‘shar-baf’. As far as I can recollect, the date inscribed on that dome was seven hundred and sixty and odd.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Since the date on the inscription today (which runs around the arch on the main façade) is not fully legible, it is difficult to confirm Haidar’s accuracy. It seems likely that the tomb was in fact erected a number of years after Tughluq Temür’s death; it was in any event paid for by his widow, Tini Khatun. The architecture and especially the tile work and calligraphy match the quality of that which remains in the better known Chaghatayid monuments in Bukhara and Samarkand. One can find many parallels in the Shah-i Zinda complex on the outskirts of the latter. The smaller tomb next to that of Tughluq Temür, a building of no apparent architectural distinction, is reputedly the burial place of his sister. The modern statue of the Chaghatayid ruler seems out of place for a Muslim shrine, the more so in that his features were being garishly gilded at the time these photographs were taken in July 2005.

Since the date on the inscription today (which runs around the arch on the main façade) is not fully legible, it is difficult to confirm Haidar’s accuracy. It seems likely that the tomb was in fact erected a number of years after Tughluq Temür’s death; it was in any event paid for by his widow, Tini Khatun. The architecture and especially the tile work and calligraphy match the quality of that which remains in the better known Chaghatayid monuments in Bukhara and Samarkand. One can find many parallels in the Shah-i Zinda complex on the outskirts of the latter. The smaller tomb next to that of Tughluq Temür, a building of no apparent architectural distinction, is reputedly the burial place of his sister. The modern statue of the Chaghatayid ruler seems out of place for a Muslim shrine, the more so in that his features were being garishly gilded at the time these photographs were taken in July 2005.

It is a pleasure to report though that the kind of hospitality Ch’ang Ch’un experienced while in Almaliq back in 1221 is still alive nearly eight centuries later. A local Uighur family spontaneously insisted that it host our small group of visitors in their home, a typical mud-brick farm compound. We enjoyed the extended family, the shade of the grape arbor and, despite our protestations that we would have only tea, a delicious meal cooked in our honor.

It is a pleasure to report though that the kind of hospitality Ch’ang Ch’un experienced while in Almaliq back in 1221 is still alive nearly eight centuries later. A local Uighur family spontaneously insisted that it host our small group of visitors in their home, a typical mud-brick farm compound. We enjoyed the extended family, the shade of the grape arbor and, despite our protestations that we would have only tea, a delicious meal cooked in our honor.

-- Daniel Waugh

The University of Washington (Seattle)

References:

W. Barthold [rev. by B. Spuler and O. Pritsak], “Almaligh,” Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd ed.

Bernard O’Kane, “Chaghatai Architecture and the Tomb of Tughluq Temür at Almaliq,” Muqarnas: An Annual on the Visual Culture of the Islamic World, 21 (2004): 277-287.

The Travels of an Alchemist: The Journey of the Taoist Ch’ang-Ch’un from China to the Hindukush at the Summons of Chingiz Khan. Recorded by His Disciple Li Chih-Ch’ang. Tr. and introd. by Arthur Waley (London: Routledge, 1931).

Ata-Malik Juvaini, The History of the World-Conqueror. Tr. J. A. Boyle. 2 v. (Cambridge, Ma.: Harvard Univ. Pr., 1958; orig. pub. by Manchester Univ. Pr.; reprinted Univ. of Washington Pr., 1997).

Mirza Muhammad Haidar, A History of the Moghuls of Central Asia, being the Tarikh-i-Rashidi. Tr. and ed. N. Elias and E. Denison Ross (London: Curzon, 1898; repr. 1972).

Back to Top

© 2006 Silk Road Seattle.

Silk Road Seattle is a project of the Walter Chapin Simpson

Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington. Additional funding has been provided by the

Silkroad Foundation (Saratoga, California).