Back to Cities and Architecture

Click on thumbnails to enlarge them

Ancient Ephesus

by

Lance Jenott

University of Washington (2004)

The city of Ephesus was one of the largest and most important cities in the ancient Mediterranean world, lying on the western coast of Asia Minor (modern day Turkey). It was one of the oldest Greek settlements on the Aegean Sea and later the provincial seat of Roman government in Asia. Situated at end of the Royal Road—the chief thoroughfare of the Roman East—the city was a western terminus of East-West trade and boasted one of the most important Mediterranean harbors for exporting products on to Greece, Italy and the rest of the Roman West. As a center of religious piety Ephesus was preeminent: the city itself developed from the earliest time around an ancient shrine of the earth goddess Artemis (Roman Diana) and became her chief place of worship. From the earliest time of the Christian era Ephesus was a key city in the expansion of Christianity. St. Paul used the city as a hub to launch proselytizing missions into Greece, and later the city was home to important cults including those of St. John and the Virgin Mary.

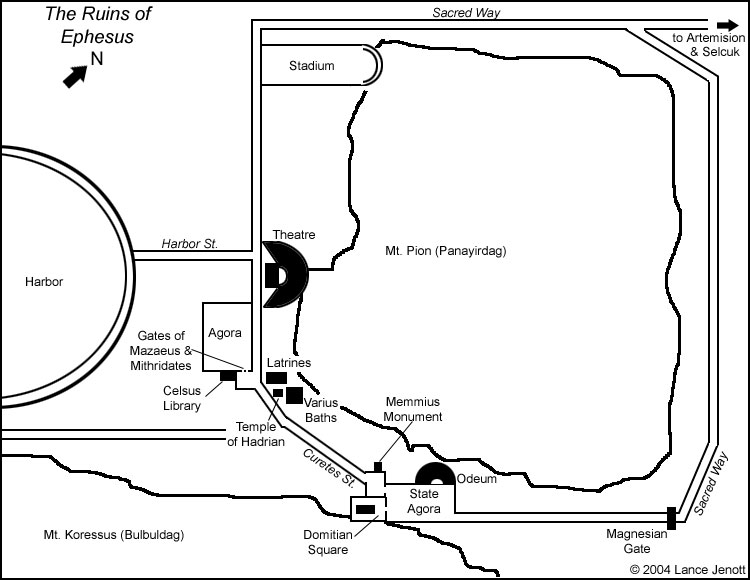

Early Bronze Age settlements apparently existed directly on the coast itself, while the settlement of the Hellenistic and Roman era lay further inland where ruins can be seen today. The city is situated in the Meander Valley in a plain south-east of the mouth of the Cayster River where it empties into the Mediterranean. To the south-west of the city is Mt. Koressus (modern Bülbüldag), to the east Mt. Pion (modern Panayirdag), while plain of arable land lie to the north between the city and river. The ancient port lay inland from the Sea about four miles and was accessible via a man-made canal cut to run eastward from the Cayster River (see city map).

Little is known of Ephesus’ origins. Greek settlements dotted the coast of Asia Minor as early as the Bronze Age (second millenium BCE) and increased during the age of Greek colonization (ca. 700 BCE). At an early time the coast of Asia Minor was divided by Aeolian cities in the north, Dorian cities in the south, and Ionian cities in the center, to which cluster Ephesus belonged. Interspersed among the Greeks were settlements of non-Greeks, such as native Anatolians and Phoenician traders.

In its early political history the city was part of the ancient kingdom of Lydia (see map of ancient Greece and Ionian coast) until that kingdom succumbed to Persian domination in the mid-sixth century BCE. But despite it’s rule by foreign powers Ephesus, along with the majority of the coastal cities, remained rooted in its Greek cultural heritage (e.g. language, architechture, fashion). When Alexander the Great defeated the Persians in the 330s Ephesus returned to Greek (or more accurately Macedonian) rule. During the ‘Age of the Successors’, that is, the time of fierce rivaly between Alexander’s generals after his death in 323, Ephesus was subject to various leaders until one general, Lysimachus (d. 281 BCE) secured the city for himself shortly after 301. Lysimachus is famous for founding the current site of the city, but soon before his death Ephesus, along with most of Asia Minor, was taken by the Seleucid kingdom and remained under its control for the rest of the century. By the beginning of the second century BCE, however, the territory had become a battleground in the struggle for power between the Seleucids and the growing hegemony of the Roman Republic which was slowly extending its way east from Italy. This tension came to a head in 190 at the Battle of Magnesia where Rome defeated the Seleucid forces in Asia Minor. Rather than incorporate its newly won territories into the Republic, Rome bestowed them to its ally Pergamum, a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by the Attalid Dynasty located north of Ephesus. Ephesus remained a possession of Pergamum until 133 BCE when upon his death Attalus III bequeathed his entire kingdom to the people of Rome in his will.

In its early political history the city was part of the ancient kingdom of Lydia (see map of ancient Greece and Ionian coast) until that kingdom succumbed to Persian domination in the mid-sixth century BCE. But despite it’s rule by foreign powers Ephesus, along with the majority of the coastal cities, remained rooted in its Greek cultural heritage (e.g. language, architechture, fashion). When Alexander the Great defeated the Persians in the 330s Ephesus returned to Greek (or more accurately Macedonian) rule. During the ‘Age of the Successors’, that is, the time of fierce rivaly between Alexander’s generals after his death in 323, Ephesus was subject to various leaders until one general, Lysimachus (d. 281 BCE) secured the city for himself shortly after 301. Lysimachus is famous for founding the current site of the city, but soon before his death Ephesus, along with most of Asia Minor, was taken by the Seleucid kingdom and remained under its control for the rest of the century. By the beginning of the second century BCE, however, the territory had become a battleground in the struggle for power between the Seleucids and the growing hegemony of the Roman Republic which was slowly extending its way east from Italy. This tension came to a head in 190 at the Battle of Magnesia where Rome defeated the Seleucid forces in Asia Minor. Rather than incorporate its newly won territories into the Republic, Rome bestowed them to its ally Pergamum, a Hellenistic kingdom ruled by the Attalid Dynasty located north of Ephesus. Ephesus remained a possession of Pergamum until 133 BCE when upon his death Attalus III bequeathed his entire kingdom to the people of Rome in his will.

Under the Roman Republic Ephesus held the technical status of a “free” city, although it was of course ultimately subject to Roman control. A city like Ephesus could pay tribute to Rome while still being considered “free” insofar as it was allowed to coin its own money and operate its own city council (boule). For a period in the late Republic the city’s economy declined due to administrative corruption (especially of the harbor) which led to an uprising and support for King Mithridates of Pontus who waged war against Rome. Mithdidates was put down, however, in 84 BCE by the Roman general Sulla who, in the aftermath of the war, did little to improve the city’s condition and even imposed a penalty tax upon the city for revolting. Four decades later Ephesus was the residence of Marc Antony and Cleopatra shortly before they were defeated at the battle of Actium by Augustus in 31 BCE, the decisive battle which is often pointed to as the beginning of the Roman imperial era.

In the Imperial era Ephesus became the seat of Roman government in the new province of Asia, while Caesar Augustus’ reforms improved the city economy and initiated a time of peace and prosperity which would last down to the third century CE. Such provincial seats were not only the city in which the provincial governor lived and conducted his judicial court: they also greatly benefited from Roman civic development necessary in arraying the city to be the face of the Roman Empire, to show the glory and greatness of Rome to the provincials. Many of the great ruins in Ephesus today were completed during the reigns of Caesar August (r.30-14 CE) and his predecessor Tiberias (r.14-37). These include, for example, the town-hall (Prytaneion), a hippodrome stadium with theatre seating in the east end, and new aqueduct lines. Throughout the Pax Romana (or ‘Roman Peace’: a time of prosperity roughly spanning from Augustus to 180 CE) civic development continued in Ephesus on a grand scale. During this time such Hellenistic sites as the famous theatre were revamped and new Roman sites like the Odeum, Library of Celsus, State Agora, bath houses and public latrines were built.

Beginning at the Magnesian Gate and walking westward along the Sacred Way on the south-east side of the city one comes to the State Agora. This Agora (usually translated as “market place” but in this case more of a “town square”) was built in the first century CE under the Flavian Emperors as the site of the Roman state cult. In the middle of the State Agora sat the temple of Divius Julius (Divine Julius Caesar) and Dea Roma (the divine personification of the Roman Empire). The temple of Isis, a popular Egyptian goddess throughout the Roman world, is also thought to have been located here.

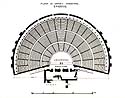

Accessible from the north end of the State Agora is the Odeum, a small semi-circle theatre where the city council (boule) assembled. According to inscriptions this Odeum was constructed ca. 150 CE under the auspices of the town clerk (at that time a powerful position) Publius Vedius Antoninus. About 112 ft. in diameter, it could sit some 2,300 people. To the front was a narrow stage about 10 ft. deep paved with white marble. Upon the stage was a colonnade of fluted white marble columns which at one time probably supported an entablature decorated with friezes. Other than city council meetings, the Odeum was used for smaller performances: lyric readings, plays, musical performances and lectures.

Accessible from the north end of the State Agora is the Odeum, a small semi-circle theatre where the city council (boule) assembled. According to inscriptions this Odeum was constructed ca. 150 CE under the auspices of the town clerk (at that time a powerful position) Publius Vedius Antoninus. About 112 ft. in diameter, it could sit some 2,300 people. To the front was a narrow stage about 10 ft. deep paved with white marble. Upon the stage was a colonnade of fluted white marble columns which at one time probably supported an entablature decorated with friezes. Other than city council meetings, the Odeum was used for smaller performances: lyric readings, plays, musical performances and lectures.

From the south-west end of the State Agora one enters the Square of Domitian, also known as the ‘Flavian Sebastoi’ or ‘Divine Flavians’: the dynasty which ruled the Empire from 69-96 CE. The square and temple were built under the last Flavian emperor, Domitian (r.81-96), who was the first to grant civic cult rights to Ephesus.

To the north-west of the Agora leading further into the city is Curetes Street (or, the Embolos) which eventually leads to the Celsus Library and the Mercantile Agora. Modern archaeologist bestowed upon it the name “Curetes” due to an apparent connection the street had with the Curetes priests, a group originally affiliated with the cult of Artemis.

To the north-west of the Agora leading further into the city is Curetes Street (or, the Embolos) which eventually leads to the Celsus Library and the Mercantile Agora. Modern archaeologist bestowed upon it the name “Curetes” due to an apparent connection the street had with the Curetes priests, a group originally affiliated with the cult of Artemis.

Continuing NW on Curetes Street, leaving the State Agora behind, one passes the Memmius Monument (first century CE) on the right. This monument is a four-sided arch dedicated to the memory of the victorious soldier Memmius, the grandson of the Roman general Sulla.

A bit further along is the little Temple of Hadrian (Roman Emperor between 117-138) built in the early to mid-second century CE. The exterior arch is supported by four columns, the outer two square, the inner two round, all with Ionian style capitals, much like the Gate of Hadrian in Athens. Featured in the middle of the arch is the bust of Tyche, the personification of the city’s fortune. Inscriptions still intact on the architrave dedicate the temple to Emperor Hadrian and more importantly reveal that the temple was constructed by Publius Vedius Antoninus, the same city clerk under whose auspices the Odeum was built.

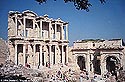

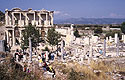

At the north-west end of Curetes Street one enters a small plaza whose most eye-catching attraction, in the ancient world and still today, is the Library of Celsus. This library, completed about 134 CE, was built as a mausoleum in honor of the Roman senator Gaius Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, a native of nearby Sardis, one time Roman Consul (an office of high distinction in Rome), and governor of Asia in 105-6 CE. Nine steps lead up from the plaza to the library’s entrance where, as one can see in the pictures here, four sets of double-columns support a two-storied portico. At intervals with three large doorways are four niches in which sit four statues representing Celsus’ cardinal virtues: Sophia (wisdom), Arete (excellence), Eunoia (benevolence), Episteme (knowledge). While the facade of the building shows a two-storied plan, the interior (one large hall) had three stories: a main floor and two balconies where scrolls stored in cubby-holes in the walls could be retrieved. Three large windows in the upper story of the exterior facade face east to allow the morning light to shine into the main reading room. In the middle of the west wall there is an apsidal niche where in antiquity there stood a statue either of Athena (according to Miltner) or Celsus himself (according to Hueber). Below the statue was the arched tomb of Celsus.

Adjacent to the Celsus library stands the Gates of Mazaeus and Mithridates, a first-century CE construction sponsored by two emancipated slaves of Caesar Augustus after whom the gates are named.

Across the plaza from the library one sees the public latrines, the Baths of Varius and the ‘House of Love’, or brothel. These latrines, built in the first century CE, are a typical example of the kind of public latrines the Romans built as a civil amenity throughout their empire. As can be seen in the picture they were constructed as a long bench with multiple holes emptying into the sewer. Typically the facilities were co-ed and no barriers separated the holes for privacy. Next to the latrine house stood the Baths of Varius, built in the second century CE by a wealthy Ephesian, P. Quintilius Varius. In the fifth century these baths were rebuilt by a wealthy woman named Skolastica. A bit north of the latrines on Marble Street, between Library and Theatre, sat the ‘House of Love’. Like other Roman brothels (for example the one preserved in Pompeii) the Ephesian brothel’s walls were decorated with mosaics portraying the working-girls.

Across the plaza from the library one sees the public latrines, the Baths of Varius and the ‘House of Love’, or brothel. These latrines, built in the first century CE, are a typical example of the kind of public latrines the Romans built as a civil amenity throughout their empire. As can be seen in the picture they were constructed as a long bench with multiple holes emptying into the sewer. Typically the facilities were co-ed and no barriers separated the holes for privacy. Next to the latrine house stood the Baths of Varius, built in the second century CE by a wealthy Ephesian, P. Quintilius Varius. In the fifth century these baths were rebuilt by a wealthy woman named Skolastica. A bit north of the latrines on Marble Street, between Library and Theatre, sat the ‘House of Love’. Like other Roman brothels (for example the one preserved in Pompeii) the Ephesian brothel’s walls were decorated with mosaics portraying the working-girls.

Passing the Celsus Library on the left and walking through the Gates of Mazaeus and Mithridates one enters the mercantile Agora (not to be confused with the State Agora discussed above), the heart of the business district of ancient Ephesus. This Agora, the market-place proper, is 112 meters square, encompassed on all four sides by a two storied stoa which presumably consisted of merchant stalls. Its construction began under the reign of Tiberius, about the year 23 CE, and was completely finished about thirty years later. According to dedicatory inscriptions, however, it appears to have been open for business by as early as 43.

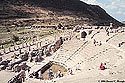

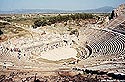

To the north of the Agora is one of the most outstanding remains of ancient Ephesus: the Great Theatre. The theatre extant today was built in the Roman period upon a much older Hellenistic foundation. Like the Odeum, but much larger, the Theatre is a semi-circular auditorium built into the western slope of Mt. Pion with orchestra pit and stage at the front. According to John Wood, who excavated it in the 1866, the theatre is 495 feet in diameter and could sit some 24,000 people in three levels of seats divided into twenty-two rows. The orchestra pit itself was 110 feet in diameter and the white marble stage 22 feet wide. Upon the stage sat a portico of granite columns supporting a two tiered entablature adorned with reliefs, such as the one seen here with a Triton blowing a shell-horn. The Theatre was used for large meetings of the entire city population (the demos), festivals like the annual procession of the city’s goddess Artemis, and any other large gathering for which the Odeum was too small. (It is very likely that this Theatre was the site of the mob protest against St. Paul reported in Acts 19.) When Wood excavated the theatre he discovered a number of inscriptions lying about the stage relating to state embassies, religious festivals, city benefactors and Roman emperors.

To the north of the Agora is one of the most outstanding remains of ancient Ephesus: the Great Theatre. The theatre extant today was built in the Roman period upon a much older Hellenistic foundation. Like the Odeum, but much larger, the Theatre is a semi-circular auditorium built into the western slope of Mt. Pion with orchestra pit and stage at the front. According to John Wood, who excavated it in the 1866, the theatre is 495 feet in diameter and could sit some 24,000 people in three levels of seats divided into twenty-two rows. The orchestra pit itself was 110 feet in diameter and the white marble stage 22 feet wide. Upon the stage sat a portico of granite columns supporting a two tiered entablature adorned with reliefs, such as the one seen here with a Triton blowing a shell-horn. The Theatre was used for large meetings of the entire city population (the demos), festivals like the annual procession of the city’s goddess Artemis, and any other large gathering for which the Odeum was too small. (It is very likely that this Theatre was the site of the mob protest against St. Paul reported in Acts 19.) When Wood excavated the theatre he discovered a number of inscriptions lying about the stage relating to state embassies, religious festivals, city benefactors and Roman emperors.

Looking west from the Theatre one can see down Harbor Street which leads to the man-made city harbor. Along this street were two gymnasiums and warehouses (undoubtedly filled with products being sent west via ship or to the eastern provinces and beyond via caravan on the Royal Road).

Looking west from the Theatre one can see down Harbor Street which leads to the man-made city harbor. Along this street were two gymnasiums and warehouses (undoubtedly filled with products being sent west via ship or to the eastern provinces and beyond via caravan on the Royal Road).

Bibliography:

Clive Foss, Ephesus after antiquity: a late antique, Byzantine, and Turkish city (Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1979)

A.H.M. Jones, The Cities of the Eastern Roman Provinces, 2nd ed. (Oxford: Claredon Press, 1971)

A.H.M. Jones, The Greek City from Alexander to Justinian (Oxford: Claredon Press, 1940)

Helmut Koester, ed., Ephesos metropolis of Asia: an interdisciplinary approach to its archaeology, religion, and culture (Valley Forge, Pa.: Trinity Press International, 1995)

William M. Ramsay, The Historical Geography of Asia Minor (Amsterdam: Adolph M. Hakkert, 1962 [reprint of London, 1890])

Franz Miltner, Ephesos: Stadt der Artemis und des Johannes (Wien: Franz Deuticke, 1958)

Friedmund Hueber, Ephesos: Gebaute Geschichte (Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern, 1997)

Wayne Meeks, The first urban Christians: the social world of the Apostle Paul (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1983)

Günther Hölbl, Zeugnisse ägyptischer Religionsvorstellungen für Ephesus (Leiden: Brill, 1978)

John Turtle Wood, Discoveries at Ephesus: including the site and remains of the great temple of Diana (1877; reprint Hildesheim; New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1975) [DF261.E5 W8]

John Ward, Greek Coins and Their Parent Cities (London: John Murray, 1902), pp.104-107, 350-352

Links:

1. Ephesus web site at Focus Online Magazine

2. Guide to Ephesus by Kusadasi.BIZ website with “virtual tours” of many of the ruins.

Back to Top

© 2004 Lance Jenott.

Silk Road Seattle is a project of the Walter Chapin Simpson

Center for the Humanities at the University of Washington. Additional funding has been provided by the

Silkroad Foundation (Saratoga, California).