Back to Traditional Culture |

Religion by Elmira Köçümkulkïzï and Daniel Waugh |

Back to Traditional Culture |

Religion by Elmira Köçümkulkïzï and Daniel Waugh |

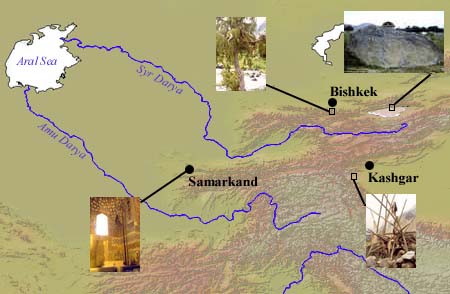

The traveler in Eurasia often encounters scenes such as these:

|

|

What are we to make of this evidence, which we might assume illustrates facets of traditional Central Asian culture? This page will provide some answers and additional illustrations. Our subject here is traditional religion in Central Asia; we begin with what has been termed "dispersed shamanism." This set of pre-Islamic traditional religious beliefs and practices has lasted into modern times, at the same time that many of its practitioners have adopted one or another of the "religions of the book": in the case of the Mongols--Buddhism; and in the case of many of the related Turkic peoples of Central Asia-- Islam. As will become evident, there is a syncretism between pre-Islamic religious tradition and Islamic norms, a fact which explains some of the distinctive features of Central Asian Islamic practice. |

Click on thumbnails to enlarge them

|

Dispersed Shamanism in North Asia

Death transforms the souls of certain people into spirits, which are thereby freed from physical human bodies and able to reside in other objects in nature. Master spirits of land had quite different characteristics. They were male and female, young and old, named, often ancestors, had experienced birth, suffering, and death, came out of their tree, water, or mountain habitations to ride or fly around, wore clothes of particular colours, took various animal and bird forms, talked to people through shamans, and often interfered in human life. They had relationships with one another, and in the landscape they had their ‘seats’, ‘running places’, and sites of notable mishaps and adventures. Above all they had personalities, feelings, and motives (p. 128). In general, rituals in North Asia are made up of action elements:

This is by no means a definitive list and it is meant only to convey the idea that there was a repertoire of ritual acts, which were often even called by the same names (or local variants) over thousands of miles in North Asia (p. 141-42).

It is difficult for most Central Asians today to distinguish today between that which is Islamic

and that which is shamanic or non-Islamic. What we might erroneously imagine should be separate

spheres share, among other things, aspects of ancestor worship. In some of the tombs and shrines

below we can see this syncretism.

|

|

There are several important Sufi "orders" each of which traces its lineage back to a particular founding teacher. In the fourteenth century, the Yasawiyya (founded by Ahmad Yasawi in the 12th century) was the most important Sufi order in much of the Timurid realm; thus Tamerlane ordered built in the 1380s the imposing mausoleum complex at Ahmad Yasawi's grave in Yas (now Turkestan city, in Southern Kazakhstan). Yasawi's shrine attracts many worshippers today and is a kind of Central Asian "Mecca." |

|

By the fifteenth century, the Naqshbandis (founded by Baha ad-Din Naqshbandi [d. 1389 and buried

near Bukhara]) became the dominant one in much of Central Asia and became actively involved in

Central Asian politics, especially in Bukhara. Connections between Babur's successors in India

and the Naqshbandi Sufi order continued to be important, since the order spread to India.

Although Islam was already well established in some regions of what is now western Xinjiang,

where there were important Sufi shrines, in the seventeenth century the Naqshbandis became the

dominant force in the region and for a time actually ruled in Kashgar. The so-called "Tomb of

the Fragrant Concubine" in Kashgar is the tomb of the Naqshbandi khojas. (When Gunnar Jarring

was in Kashgar in 1930, he photographed a huge pile of Marco Polo sheep horns in front of this

otherwise Islamic tomb; see Return to Kashgar, p. 192.) The Naqshbandis even extended their

influence into China proper.

|

|

While the subject merits detailed separate treatment and thus will merely be broached here, it is important to remember that the formal, learned manifestations of Islam have a long history in the urban centers especially of southern Central Asia. Ata-Malik Juvaini, the thirteenth-century Persian chronicler of Chingis Khan lauded pre-conquest Bukhara: In the Eastern countries it is the cupola of Islam and is in those regions like unto the City of Peace [=Baghdad]. Its environs are adorned with the brightness of the light of doctors and jurists and its surroundings embellished with the rarest of high attainments. Since ancient times it has in every age been the place of assembly of the great savants of every religion [Boyle transl., pp. 97-98]. |

|

More than a century after Juvaini wrote, in the time of Tamerlane and his successors, formal Islamic learning (including science) flourished in Samarkand. Later still, toward the end of Bukhara's independence in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the city was known as a stronghold of "conservative" Islam at a time when muslim leaders in many areas of the Russian Empire were beginning to advocate "westernizing" education. The only officially authorized muslim religious school (medrese) allowed to operate in much of the Soviet period in Central Asia was the Mir-i Arab Medrese, shown here across from the twelfth-century Kalyan Minaret. |

|

Central Asian shrines

|

|

|

To illustrate the physical evidence of religious beliefs amongst the early nomads of Eurasia, we might start with the ubiquitous petroglyphs which at many sites are considered to be more than three thousand years old. These pictographic drawings of horned animals such as ibex and mountain goats (often accompanied by hunters) are found all over the Central Asian territory inhabited by various ancient nomadic tribes and tribal confederations. A particularly impressive group of them, shown in the first three pictures here, is in a boulder field on the outskirts of the city of Cholpon-Ata in northeastern part of Kyrgyzstan. A fourth picture shows analogous depictions on a cliff face above a small valley in Gansu Provice, China; other examples could be produced from Mongolia, Kazakhstan, Northern Pakistan and Northern India. Animals played a significant role in hunting as well as pastoral societies of Central Asian nomads, who revered certain animals as their totem ancestor. In their shamanic worldview, all the horned animals had their master-spirit or protector named Kayberen. People worshipped all kinds animal spirits, including the master-spirit of Kayberen, for they were believed to have soul, feelings like human beings and supernatural power to harm people if they were mistreated. Therefore, traditionally, hunters, accompanied by shamans, before they killed any horned animal, first had to please the master spirit of animals by imitating their animal behaviors. Since these pictographs are to be found in otherwise quite ordinary natural settings, drawing the pictures of mountain goats on rocks may have been one of the ways of worshipping or pleasing their master-spirit. Central Asian traditional applied art (for example, various woven textiles) consists primarily of ornaments and designs reflecting various types of animal horns. |

|

Also among the oldest evidence connected with the nomads' religious beliefs are the stone figures called balbals. They are found scattered across the steppe regions and pastures of Inner Asia. One example here is lying in the grass near the petroglyphs at Cholpon-Ata; the other examples were brought together from various areas to create an open air museum of balbals next to the Burana tower in the town of Tokmok near Bishkek, capital city of Kyrgyzstan. This was apparently one of the capitals of Turkic Karakhanid state, which flourished in the tenth-eleventh centuries C.E. Many other examples have been found in the area of the Kipchak nomads north of the Caspian and Black Seas and in the northwestern part of Mongolia where inscriptions have been found which refer to Kültegin, the khan of the sixth-century first Turkic Empire. It has been said that these balbal stone figures represent the defeated enemies of the Turkic khans and were erected in honor of deceased khans. Excavation under balbals has in some cases revealed burials. All of the balbal figures hold a cup at chest level. The holding of the cup is said to symbolize the enemy’s submission and offering its service to their master in the next world. |

|

|

|

|

As one Daur Mongol woman also noted: "The Daurs do not think that there is a soul in all things. They think that only those beings which are alive have souls. If people see mountains, water, and trees as having souls this is because some shamanic master soul has been put in, and because of this people say they have souls, but this is not really a soul of the mountain, water, or tree. Daur shamans never worship land spirits they only worship their own dead shamans’ spirits." (Humphrey, p. 132) |

|

|

|

|

|

The photo here provides an example of another way such worship may be expressed, by the tying of strips of cloth to the branches of a bush or tree. Located on the curve of a road above the main reservoir north of Tashkent in Uzbekistan, this site could be one where auto accidents have claimed lives, or it could simply be a location marked as a special one because of its panoramic view. Many springs along the roads in Central Asia are similarly marked by tying of strips of cloth to branches of surrounding bushes. The practice also can be observed in many Islamic regions on trees adjoining important shrines. (See the linked page above, for Solomon's Mountain in Osh.) |

|

It is not uncommon to see Muslim graves where the connection of animals with the deceased is commemorated. Next to the Karakorum Highway overlooking Lake Karakul in a Kyrgyz region of western Xinjiang, China, is a Muslim graveyard which has typical domed tombs. Next to one of the tombs though is an unusual grave. On top of it is a rope, one end of which is tied to a stick and the other end buried in the ground. Very likely this is a horse’s grave, so sharply contrasting in form from the adjoining Muslim burials. Possibly the horse was killed and buried together with his owner. We know from archeological findings in Central Asia that in the past when a man died his favorite horse as well as other necessary objects and belongings were buried with him. Caroline Humphrey’s account of the burial customs of the Daur Mongols provides a good example: "While the corpse was lying at home a saddled horse (hwailag) was tethered outside in the yard. A thin rope was attached from the corpse, near the head, to the animal. Urgunge [co-author of the book] thought this string was a ‘rein’, though he was not sure, and that the horse was the soul’s mount on its journey to the other world. The horse should be elderly and castrated male, one the deceased’s much-used animals. The horse was killed and its heart, liver, lungs, and spleen removed, cooked, and placed beside the coffin. The rest of the meat was eaten . . . [Humphrey, p. 195.] |

|

Not far from Lake Karakul, in the same Kyrgyz region of Xinjiang but up in remote mountain valleys, there are different

shrines, which the local herders indicate also mark burials. They are characterized by an array of poles, at the ends of which

are tied yak tails and to which strips of cloth may be attached. At the base of the poles is an array of ibex or mountain goat

horns. In form, these shrines resemble sacred cairns or oboos, which are widespread in Eurasia and are often located at high

points (the tops of hills or on mountain passes). In North Asia, every spring and autumn, Mongols, Buryats, and Daurs

conducted oboo rituals in spring and autumn by piling up trees and stones. They sacrificed animals to various forces of nature

such as mountains, hills, cliffs, and rivers, but most importantly to tengger (Turkic/Mongol word for sky and God). People

prayed "for human prosperity, for male descendants, for timely rain, wind, warmth, for the elimination of calamities, storms,

and cattle diseases, for abundance of the five cereal crops, the flourishing of domestic livestock, and the banishing of ticks and

crop-eating insects . . . Large oboo rituals were always followed by the "manly sports’ of archery, wrestling, field-hockey, and

horse-racing" (Humphrey, p. 148).

The bones were not burned but left at the site. Incense was burned, bowls of alcohol and blood thrown to the cairn. The meat was then laid out piece by piece in the shape of the animal in a big container and placed to the front of the cairn (south). The participating men stood in order of genealogical seniority and an officiant, either the clan elder or the bagchi, would pronounce the prayers. In rhymed speech he asked the mountain spirit to ‘come down’, to deign to grant the people’s requests and accept the offering. The participants splashed water all over the cairn and one another, and then they again circumambulated the site three times in the direction of the sun. Finally they had a big feast. The cooked meat was thought to be blessed by the mountain spirit and by heaven. Giving the deity food to eat was not the important meaning given to the rite; rather the meat was offered as a sign of reverence, and, one might say, as a material medium for the blessing (keshi) which was received in return. The splashed water was said to signify the rain which the clan described. Finally, the head, skin, and hooves of the sacrificed animal were hung on a tall pole facing the sky in a south-pointing direction, and left to the ravages of the weather...Male fertility is commonly associated with oboos. The Mongols and Daurs put the skulls of favourite horses on oboos; when the skull is that of a stallion people take their mares to the spot to ensure it will bear young. [Humphrey, pp. 147-149.] |

|

Here are two Kyrgyz examples of what it seems reasonable to interpret as oboos. The first is a collection of animal horns on top of a rock outcrop overlooking the Kengxuwar River not far from the snout of the Kuksay Glacier on the south side of Mt. Mustagh Ata in Xinjiang. That this collection of horns was not simply a random dump next to a hunter/herder camp is suggested by the fact they are contained within a low stone wall. The second example is quite different, a sizeable pile of stones at a high point on a trail in the Karavshin Valley in southern Kyrgyzstan. Not far away from this oboo was a grave, and a bit farther along the trail was a mosque (discussed below). It is a common ritual practice to add a stone as one passes an oboo. Similarly stones may be placed on a grave or other object which has sacred significance. One even sees small cairns erected on the top of unusual large boulders. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Back to Top |

© 2001 Elmira Köçümkulkïzï and Daniel C. Waugh.

|