Edited by Lance Jenott (2001)

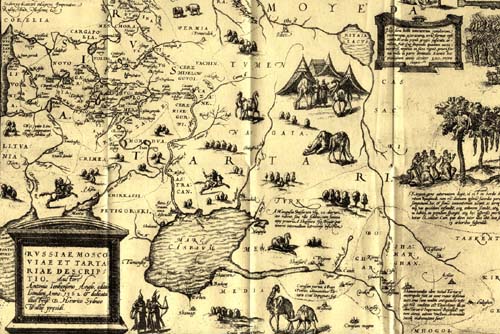

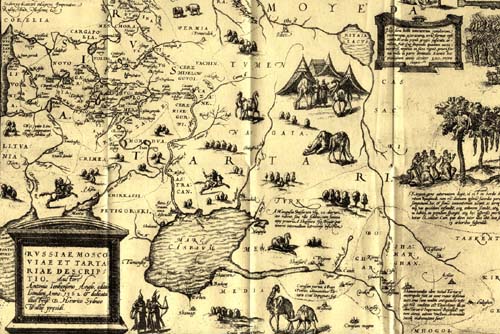

The Jenkinson Map (Click on each quadrant to enlarge it)

Edited by Lance Jenott (2001)

The Jenkinson Map (Click on each quadrant to enlarge it)

TABLE OF CONTENTS:

INTRODUCTION:

It was the possibility of a Northeast passage to Cathay that led a group of English entrepreneurs

to finance an exploratory mission in 1553 under the command of two ship-captains,

Hugh Willoughby and Richard Chancellor. When the explorers rounded the northern coasts of

Norway and Sweden, Willoughby and two ships were lost, but Chancellor managed to pilot his

ship into the White Sea, thus ďdiscoveringĒ the northern Russian port of St. Nicholas and

moreover, a direct sea route to Russia. Chancellor returned to England in 1554, after attending

Tsar Ivan IVís court in Moscow where he received promising words that English merchants

would be accommodated if they desired to trade in the tsarís domain. By 1555 the English financiers

received a royal charter making them an official company, generally known as the Russia or Muscovy Company.

With the Company established, the English carried on a regular and direct trade with Russia via the

northern route to the White Sea throughout the following decades.

Although the Company had successfully established itself in Russia it did not lose sight of its

original purpose: establishing direct trade connections with China. In 1556 another exploratory

mission was dispatched to explore the waters east of the White Sea, but after reaching the island

of Vaigach (off the coast of northern Russia) it was forced to turn back due to hazardous sailing

conditions. It may have been the failure of this sea mission that led to a stronger interest in

exploring overland eastern routes, for in the next year (1557) the company dispatched its factor

Anthony Jenkinson to Moscow with instructions to seek passage through the tsarís domain in

order to explore routes to Central Asia, Persia, and ultimately China. The political situation in

Russia was particularly accommodating to this mission, because the tsar had recently extended

the boundaries of Russia to the east (at the expense of the Tartar khanates) as far as the north

shore of the Caspian Sea.

After being granted a license to travel, as well as receiving letters from the tsar addressed to

foreign kings asking for his safe-conduct, Jenkinson, a Tartar interpreter, and two other company

employees, Richard and Robert Johnson, departed Moscow eastward in April 1558. In

Astrakhan they joined a group of local merchants, sailed across the Caspian and from thence

traveled east overland with the ultimate goal of reaching China. By December they had reached

the famous Central Asian city of Bukhara, but were forced to turn back after learning that the

routes beyond had been ravished by war. The explorers returned to Moscow in September 1559.

The account which follows is Jenkinsonís letter reporting the missionís events to his employers

in England. It was written in 1560 in Kholomogory, Russia, while Jenkinson waited to sail to

England. It is perhaps most significant because it is one of the first European reports on the

conditions of trade in Inner Asia and the regions adjoining the Caspian Sea since the tradeís

decline. The report gives particular attention to the various locations along the routes, the travel

time from one location to the next, the conditions, situation, products and merchants of the

regions, and especially the often over-looked details of the difficult and hazardous experience of

travel in the sixteenth century. Overall, it explains the challenges in reestablishing the overland

route to the Far East.

Following Jenkinsonís report, the Company in subsequent years dedicated less attention to the

establishment of trade to the Far East, and focused more on cultivating trade with Persia. Some

activity, however, shows that the Company still desired to open routes east. In 1568 a mission was

planned to explore the sea route east of the White Sea, but never came about. The final attempt of

the century was made in 1580. This mission was also directed at exploring the northern sea

route, and also failed for much the same reasons as had the earlier missions.

[pp. 451-453]

The 27th day we passed by another castle called Swyasko, distant from Sabowshare aforesaid 25

leagues: we left it one our right hand, and the 29th came unto an island one league from the city

of Cazan, from which falleth down a river called Cazanka Reca [=Kazanskaia reka], & entereth into the aforesaid

Volga. Cazan is a fair town after the Russe or Tartar fashion, with a strong castle, situated upon

a high hill, and was walled round about with timber & earth, but now the Emperor of Russia hath

given order to pluck down the old walls, and to build them again of free stone. It hath been a

city of great wealth and riches, and being in the hands of the Tartars it was a kingdom of itself,

and did more vex the Russes in their wars, then any other nation: but 9 years past [actually

1552], this Emperor of Russia conquered it, and took the king captive, who being but young is

now baptized, and brought up in his court with two other princes, which were also kings of the

said Cazan, and being each of them in time of their reigns in danger of their subjects through

civil discord, came and rendered themselves at several times unto the said Emperor, so that at

this present there are three princes in the court of Russia, which had been Emperors of the said

Cazan, whom the Emperor useth with great honor.

We remained at Cazan till the 13th day of June and then departed from thence: and the same day

passed by an island called the Island of Merchants, because it was wont to be a place where all

merchants, as well Russes and Cazanites, and Nagyans and Crimmes, and divers other nations

did resort to keep mart for buying and selling, but now it is forsaken, and standeth without any

such resort thither, or at Cazan, or at any place about it, from Mosco unto Mare Caspium.

Thus proceeding forward the 14th day, we passed by a goodly river called Cama [=Kama],

which we left on our left hand. This river falleth out of the country of Permia into the river

Volga, and is from Cazan 15 leagues: and the country lying betwixt the said Cazan and the said

river Cama on the left hand of the Volga is called Vachen [=Viatka?], and the inhabitants be Gentiles, and

live in the wilderness without house or habitation: and the country on the other side of the Volga

over against the said river Cama is called the land of Cheremizes, half Gentiles, half Tartars, and

all the land on the left hand of the said Volga from the said river to Astracan, and so following

the north and northeast side of the Caspian Sea, to a land of the Tartars called Turkeman, is

called the country of Mangat or Nagay, whose inhabitants are of the law of Mahomet, and were

all destroyed in the year 1558, at my being at Astracan, through civil wars among them,

accompanied with famine, pestilence, and such plagues, in such sort that in the said year there

were consumed of the people, in one sort and another, above one hundred thousand: the like

plague was never seen in those parts, so that the said country of the Nagay being a country of

great pasture, remaineth now unreplenished to the great contentation of the Russes, who have

had cruel wars a long time together.

The Nagayans when they flourished, lived in this manner: they were divided into divers

companies called Hordes, and every Horde had a ruler, whom they obeyed as their king, and was

called a Murse [=Mirza]. Town or house they had none, but lived in the open fields, every Murse or king

having his Hordes or people about him, with their wives, children and cattle, who having

consumed the pasture in one place, removed unto another and when they remove they have

houses like tents set upon wagons or carts, which are drawn from place to place with camels, &

therein their wives, children, and all their riches, which is very little, is carried about, and every

man hath at the least four or five wives besides concubines. Use of money they have none, but

do barter their cattle for apparel and other necessaries. They delight in no art nor science, except

the wars, wherein they are expert, but for the most part they be pasturing people, and have great

store of cattle, which is all their riches. They eat much flesh, and especially the horse, and they

drink mares milk, wherewith they be often times drunk: they are seditious and inclined to theft

and murder. Corn they sow not, neither do they eat any bread, mocking the Christians for the

same, and disabling our strengths, saying we live by eating the top of a weed, and drink a drink

made of the same, allowing their great devouring of flesh, and drink of milk to be the increase of

their strength. But now to proceed forward to my journey.

[pp. 453-454]

All the country upon our right hand the river Volga, from over against the river Cama unto the

town of Astracan, is the land of the Crimme [=Crimea], whose inhabitants be also of the law of Mahomet,

and live for the most part according to the fashions of the Nagayes, having continual wars with

the Emperor of Russia, and are valiant in the field, having countenance, and support from the

Great Turke [=Ottoman Sultan].

The 16th day of June we passed by certain fishermensí houses called Petowse twenty leagues

from the river Cama, where [there] is great fishing for sturgeon, so continuing our way until the

22nd day, and passing by another great river called Samar [=Samara], which falleth out of the aforesaid

country, and runneth through Nagay, and entereth into the said river of Volga. The 28th day we

came unto a great hill, where was in times past a castle made by the Crimmes, but now it is

ruined, being the just midway between the said Cazan and Astracan, which is 200 leagues or

thereabout, in the latitude of 51 degrees 47 minutes. Upon all this shore groweth [an] abundance

of licorice, whose root runneth within the ground like a vine.

Thus going forward the sixth day of July we came to a place called Perovolog [=Perevolok], so named because

in times past the Tartars carried their boats from Volga unto the river Tanais, otherwise called

Don, by land, when they would rob such as passed down the said Volga to Astracan, and also

such as passed down by the river Tanais, to Asov, Caffa, or any other town situated

upon Mare Euxinum [=Black Sea], into which sea Tanais falleth, who hath his springs in the

country of Rezan, out of a plane ground. It is at this straight of Perovolog from the one river to

the other two leagues by land, and is a dangerous place for thieves and robbers, but now it is not

so evil as it hath been, by reason of the Emperor of Russia his conquests.

Departing from Perovolog, having the wilderness on both sides, we saw a great heard of

Nagayans, pasturing, as is abovesaid, by estimation above a thousand camels drawing of carts

with houses upon them like tents, of a strange fashion, seeming to be afar off a town: that Horde

was belonging to a great Murse called Smille, the greatest prince in all Nagay, who hath slain

and driven away all the rest, not sparing his own brethren and children, and having peace with

this Emperor of Russia he hath what he needeth, and ruleth alone: so that now the Russes live in

peace with the Nagays, who were wont to have mortal wars together.

[pp. 454-455]

The 14th day of July passing by an old castle, which was old Astracan, and leaving it upon our

right hand, we arrived at new Astracan, which this Emperor of Russia conquered six years past,

in the year 1552 [actually 1556]. It is from the Mosco unto Astracan six hundred leagues, or

thereabout. The town of Astracan is situated in an island upon a hill side, having a castle within

the same, walled about with earth and timber, neither fair nor strong: The town is also walled

about with earth: the buildings and houses (except it be the captainís lodging, and certain other

gentlemensí) most base and simple. The island is most destitute and barren of wood and pasture,

and the ground will bare no corn: the air is there most infected, by reason (as I suppose) of much

fish, and specially sturgeon, by which only the inhabitants live, having great scarcity of flesh and

bread. They hang up their fish in their streets and houses to dry for their provisions, which

causeth such abundance of flies to increase there, as the like was never seen in any land, to their

great plague. And at my being at the said Astracan, there was a great famine and plague among

the people, and specially among the Tartars called Nagayans, who the same time came thither in

great numbers to render themselves to the Russes their enemies, & to seek succor at their hands,

their country being destroyed, as I said before: but they were but ill entertained or relieved, for

there died a great number of them for hunger, which lay all the island through in heaps dead, and

like to beasts unburied, very pitiful to behold: many of them were also sold by the Russes, and

the rest were banished from the island. At that time it had been an easy thing to have converted

that wicked nation to the Christian faith, if the Russes themselves had been good Christians: but

how should they show compassion unto other nations, when they are not merciful unto their

own? At my being there I could have bought many goodly Tartarsí children, if I would have had

a thousand, of their own fathers and mothers, to say, a boy or a wench for a loaf of bread worth

six pence in England, but we had more need of victuals at that time then of any such

merchandise. This Astracan is the furthest hold that this Emperor of Russia hath conquered of

the Tartars towards the Caspian Sea, which he keepeth very strong, sending thither every year

provisions of men and victuals, and timber to build the castle.

[p. 456]

There is a certain trade of merchandise there used, but yet so small and beggarly, that it is not

worth the making mention, and yet there come merchants thither from divers places. The

chiefest commodities that the Russes bring there are red hides, red sheepís skins, wooden

vessels, bridles and saddles, knives, and other trifles, with corn, bacon, and other victuals. The

Tartars bring thither divers kinds of wrought silks: and they that come out of Persia, namely from

Shamacki, do bring sowing silk, which is the coarsest that they use in Russeland, crasko, divers

kinds of pied silks for girdles, shirts of mail, bows, swords, and such like things: and years

quantity, the merchants being so beggarly and poor that bring the same, that it is not worth the

writing, neither is there any hope of trade in all those parts worth the following.

This aforesaid island of Astracan is in length twelve leagues, and in breadth three, & lieth east

and west in the latitude of forty-seven degrees, nine minutes: We tarried there until the sixth day

of August, and having bought and provided a boat in company with certain Tartars and Persians,

we laded our goods and embarked ourselves, and the same day departed I, with the said two

Johnsons having the whole charge of the navigation down the said river Volga, being very

crooked, and full of flats toward the mouth thereof. We entered into the Caspian Sea the tenth

day of August at the easterly side of the said river, being twenty leagues from Astracan aforesaid,

in the latitude of forty six degrees, twenty seven minutes.

SAILING ON THE CASPIAN

[The] Volga hath seventy mouths of falls into the sea: and we having a large wind, kept the

Northeast shore and the eleventh day we sailed seven leagues east-northeast, and came unto an

island having an high hill therein, called Accurgar, a good mark in the sea.

[pp. 457-459]

From thence east ten leagues, we fell with another island called Bawhiata, much higher then the

other. Within these two islands to the northwards, is a great bay called the Blue Sea. From

thence we sailed East and North ten leagues, and having a contrary wind, we came to an anchor

in a fathom water, and so rid until the fifteenth day, having a great storm at southeast, being

most contrary wind, which we rid out. Then the wind came to the north, and we weighed [i.e.,

raised anchor], and set our course southeast, and that day sailed eight leagues.

Thus proceeding forwards, the 17th day we lost sight of land, and the same day sailed thirty

leagues, and the 18th day twenty leagues winding east, and fell with a land called Baughleata,

being 74 leagues from the mouth of the said Volga, in the latitude of 46 degrees 54 minutes, the

coast lying nearest east and by south, and west and by north. At the point of this land lieth

buried a holy prophet, as the Tartars call him, of their law, where great devotion is used of all

such Mahometists as do pass that way.

The nineteenth day the wind being west, and we winding east-southeast, we sailed ten leagues,

and passed by a great river called Iaic [=Yaik/Ural], which hath his spring in the land of Siberia,

nigh unto the aforesaid river Cama, and runneth through the land of Nagay, falling into this Mare

Caspium. And up this river one days journey is a town called Serachick, subject to the aforesaid

Tartar prince called Murse Smille, which is now in friendship with the Emperor of Russia. Here

is no trade of merchandise used, for that the people have no use of money, and are all men of

war, and pasturers of cattle, and given much to theft and murder. Thus being at an anchor

against this river Iaic, and all our men being on land, saving I, who lay sore sick, and five

Tartars, whereof one was reputed a holy man, because he came from Mecka [=Mecca], there

came unto us a boat with thirty men well armed and appointed, who boarded us, and began to

enter into our bark, and our holy Tartar called Azi, perceiving that, asked them what they would

have, and withal made a prayer: with that these rovers stayed, declaring that they were

gentlemen, banished from their country, and out of living, & came to see if there were any

Russes or other Christians (which they call Caphars) in our bark? To whom this Azi most

stoutly answered, that there were none avowing the same by great others of their law (which

lightly they will not break) whom the rovers believed, and upon his words departed. And so

through the fidelity of that Tartar, I with all my company and goods were saved, and our men

being come on board, and the wind fair, we departed from that place, and winding east and

southeast, that being the 20th of August sailed 16 leagues.

The 21st day we passed over a bay of 6 leagues broad, and fell with a cape of land, having two

islands at the southeast part thereof, being a good mark in the sea: & doubling that cape the land

trended northeast, and maketh another bay, into which falleth the great river Yem [=Emba], springing out

of the land of Colmack [=Kalmyks]. The 22nd, 23rd [and] 24th days, we were at an anchor. The 25th the

wind came fair, and we sailed that day 20 leagues, and passed an island of low land and there

about are many flats and sands: and to the northward of this island there goeth in a great bay, but

we set off from this island, and winded south to come into deep water, being much troubled with

shoals & flats, and ran that course 10 leagues, then east-southeast 20 leagues, and fell with the

mainland, being full of copped hills, and passing along the coast 20 leagues, the further we

sailed, the higher was the land.

CARAVANING TURKISTAN

The 27th day we crossed over a bay, the south shore being the higher land, and fell with a high

point of land: & being overthwart the cape, there rose such a storm at the east, that we thought

verily we should have perished: this storm continued 3 days. From this cape we passed to a port

called Manguslave. The place where we should have arrived at the southern-most part of the

Caspian Sea, is 12 leagues within a bay: but we being sore tormented and tossed with this

aforesaid storm, were driven unto another land on ye other side [of] the bay, overthwart the said

Manguslave [=Mangyshlak] being very low land, and a place as well for the ill commodity of the haven, as of

those brute field people, where never bark nor boat had before arrived, not liked of us.

[pp. 459-461]

But yet here we sent certain of our men to land to talk with the governor and people, as well for

our good usage at their hands, as also for provision of camels to carry our goods from the said

sea side to a place called Sellizure, being from the place of our landing five and twenty days

journey. Our messengers returned with comfortable words and fair promises of all things.

Wherefore the 3rd day of September 1558 we discharged our bark, and I with my company were

gently entertained of the Prince & of his people. But before our departure from thence, we found

them to be very bad and brutish people, for they ceased not daily to molest us, either by fighting,

stealing or begging, raising the price of horse and camels, & victuals, double that it was wont

there to be, and forced us to buy the water that we did drink: which caused us to hasten away and

to conclude with them as well for the hire of camels, as for the price of such as we bought, with

other provision, according to their own demand: So that for every camels lading, being but 400

weight of ours, we agreed to give three hides of Russia and four wooden dishes, and to the

prince or governor of the said people, one ninth, and two seventh: namely, nine several things,

and twice seven several things: for money they use none.

And thus being ready, the fourteenth of September we departed from that place, being a caravan

of a thousand camels. And having traveled five days journey, we came to another princeís

dominion, and upon the way there came unto us certain Tartars on horseback, being well armed,

and servants unto the said prince called Timor Soltan [=Timur Sultan, ruler of Khwarezm], governor of the said country of

Manguslave, where we meant to have arrived and discharged our bark, if the great storm

aforesaid had not disappointed. These aforesaid Tartars stayedmmanding me to be well feasted with

flesh and mares milk: for bread they use none, nor other drink except water: but money he had

none to give me for such things as he took of me, which might be of value in Russe money,

fifteen rubbles, but gave me his letter, and a horse worth seven rubbles. And so I departed from

him being glad that I was gone: for he was reported to be a very tyrant, and if I had not gone unto

him, I understood his commands was, that I should have been robbed and destroyed.

This soltan lived in the fields without castle or town, and sat, at my being with him, in a little

round house made of reeds covered without with felt, and within with carpets. There was with

him the great metropolitan of that wild country, esteemed of the people, as the Bishop of Rome

is in most parts of Europe, with divers other of his chief men. The soltan with this metropolitan

demanded of me many questions, as well touching our kingdoms, laws, and religion, as also the

cause of my coming into those parts, with my further pretence. To whom I answered concerning

all things, as unto me seemed best, which they took in good part. So having leave I departed and

overtook our caravan, and proceeded on our journey, and traveled 20 days in the wilderness from

the sea side without seeing town or habitation, carrying provision of victuals with us for the same

time, and were driven by necessity to eat one of my camels and a horse for our part, as other[s]

did the like: and during the said 20 days we found no water, but such as we drew out of old deep

wells, being very brackish and salt, and yet sometimes passed two or three days without the

same. And the 5th day of October ensuing, we came unto a gulf of the Caspian Sea again, where

we found water very fresh and sweet: at this gulf the customers of the king of Turkeman met us,

who took custom of every 25th one, and 7 ninths for the said king and his brethren, which being

received they departed, and we remained there a day after to refresh our selves.

[pp. 461-463]

Note that in times past there did fall into this gulf the great river Oxus, which hath his springs in

the mountain of Paraponisus in India, & now commeth not so far, but falleth into another river

called Ardock, which runneth toward the north & consumeth himself in the ground passing under

ground above 500 miles, and then issueth out again and falleth into the lake of Kithay [=Aral

Sea?].

We having refreshed our selves at the aforesaid gulf, departed thence the 4th day of October, and

the seventh day arrived at a castle called Sellizure, where ye king called Azim Can [=Khan],

remained with 3 other of his brethren and the 9th day I was commanded to come before his

presence, to whom I delivered the Emperorís letters of Russia: and I also gave him a present of a

ninth, who entertained me very well, and caused me to eat in his presence as his brethren did,

feasting me with flesh of a wild horse, and mares milk without bread. And the next day he sent

for me again, and asked me divers questions, as well touching the affairs of the Emperor of

Russia, as of our country and laws, to which I answered as I thought good: so that at my

departure he gave me his letters of safe conduct.

This castle of Sellizure is situated upon an high hill, where the king called the Can [=khan] lieth, whose

palace is built of earth very basely, and not strong: the people are but poor, and have little trade

of merchandise among them. The south part of this castle is low land, but very fruitful, where

grow many good fruits, among which there is one called a Dynie [=Dynia Arbus], of a great bigness and full of

moisture, which the people do eat after meat in stead of drink. Also there grows another fruit

called a Carbuse of the bigness of a great cucumber, yellow and sweet as sugar: also a certain

corn called Iegur, whose stalk is much like a sugar cane, and as high, and the grain like rice,

which groweth at the top of the cane like a cluster of grapes; the water that serveth all that

country is drawn by ditches out of the river Oxus, unto the great destruction of the said river, for

which cause it falleth not into the Caspian Sea as it hath done in times past, and in short time all

that land is like to be destroyed, and to become a wilderness for want of water, when the river of

Oxus shall fail.

THE CITY OF URGENCH

The 14th day of the month we departed from this castle of Sellizure, and the 16th of the same we

arrived at a city called Urgench, where we paid custom as well for our own heads, as for our

camels and horses. And having there sojourned one month, attending the time of our further

travel, the king of that country called Ali Soltan, brother to the forenamed Azim Can, returned

from a town called Corasan [=Khorasan], within the borders of Persia, which he lately had

conquered from the Persians, with whom he and the rest of the kings of Tartaria have continual

wars. Before this king also I was commanded to come, to whom I likewise presented the

Emperorís letters of Russia, and he entertained me well, and demanded of me divers questions,

and at my departure gave me his letters of safe-conduct.

[pp. 463-465]

This city or town of Urgence standeth in a plane ground, with walls of the earth, by estimation 4

miles about it. The buildings within it are also of earth but ruined and out of good order: it hath

one long street that is covered above, which is the place of their market. It hath been won and

lost 4 times within 7 years by civil war, by means thereof there are but few merchants in it, and

they very poor, and in all that town I could not sell above 4 kersies. The chiefest commodities

there sold are such wares as come from Boghar [=Bukhara], and out of Persia, but in most small

quantity not worth the writing. All the land from the Caspian Sea to this city of Urgence is

called the land of Turkeman, & is subject to the said Azim Can, and his brethren which be five in

number, and one of them hath the name of the chief king called Can, but he is little obeyed

saving in his own dominion, and where he dwelleth: for every one will be king of his own

portion, and one brother seeketh always to destroy another, having no natural love among them,

by reason that they are begotten of divers women, and commonly they are the children of slaves,

either Christian or Gentiles, which the father doeth keep as concubines, and every Can or Sultan

hath at the least 4 or 5 wives, besides young maidens and boys, living most viciously: and when

there are wars betwixt these brethren (as they are seldom without) he that is overcome if he be

not slain, flieth to the field with such company of men as will follow him, and there liveth in the

wilderness resorting to watering places, and so robbeth and spoileth as many caravans of

merchants and others as they be able to overcome, continuing in this sort his wicked life, until

such time as he may get power and aid to invade some of his brethren again.

NOMADIC LIFE

From the Caspian

Sea unto the castle of Sellizure aforesaid, and all the countries about the said sea, the people live

without town or habitation in the wild fields, removing from one place to another in great

companies with their cattle, whereof they have great store, as camels, horses, and sheep both

tame and wild. Their sheep are of great stature with great buttocks, weighing 60 or 80 pound in

weight. There are many wild horses which the Tartars do many times kill with their hawks, and

that in this order.

The hawks are lured to seize upon the beastsí necks or heads, which with chasing of themselves

and sore beating of the hawks are tired: then the hunter following his game doeth slay the horse

with his arrow or sword. In all this land there groweth no grass, but a certain brush or heath,

whereon the cattle feeding become very fat.

The Tartars never ride without their bow, arrows, and sword, although it be on hawking, or on

any other pleasure, and they are good archers both on horse back, and on foot also. These people

have not the use of gold, silver, or any other coin, but when they lack apparel or any other

necessaries, they barter their cattle for the same. Bread they have none, for they neither till nor

sow: they be great devourers of flesh, which they cut in small pieces, & eat it by handfuls most

greedily, & especially the horseflesh. Their chiefest drink is mares milk soured, as I have said

before of the Nagayans, & they will be drunk with the same. They have no rivers nor places of

water in this country, until you come to the aforesaid gulf, distant from the place of our landing 20

days journey and more. They eat their meat upon the ground, sitting with their legs double under

them, and so also when they pray. Art or science they have none, but live most idly, sitting

round in great companies in the fields, devising, and talking most vainly.

URGENCE TO KAIT

The 26th day of November, we departed from the town of Urgence, and having traveled by the

river Oxus, 100 mile[s], we passed over another great river called Ardock, where we paid a

certain petty custom. This river Ardock is great, and very swift, falling out of the aforesaid

Oxus, and passing about 1000 miles to the northward, it then consumeth itself in the ground, and

passing under the same about 500 mile, issueth out again, and falleth into the lake of Kitay, as I

have before declared.

[p. 465]

The 7th day of December following, we arrived at a castle called Kait [=Kat?], subject to a soltan called

Saramet Soltan, who meant to have robbed all the Christians in the caravan, had it not been for

fear of his brother the king or Urgence, as we were informed by one of his chiefest counselors,

who willed us to make him a present, which he took, and delivered: besides, we paid at the said

castle for custom, of every camel one red hide of Russia, besides petty gifts to his officers.

CARAVAN BANDITS

Thus proceeding in our journey, the tenth day at night being at rest, and our watch set, there

came unto us four horsemen, which we took as spies, from whom we took their weapons and

bound them, and having well examined them, they confessed that they had seen the tract of many

horsemen, and no footing of camels, & gave us to understand, that there were rovers and thieves

abroad: for there travel few people that are true and peaceable in the country, but in company of

caravan, where there be many camels: and horse-feeting new without camels were to be doubted.

Where upon we consulted & determined amongst ourselves, and sent a post to the said soltan of

Kait, who immediately came himself with 300 men, and met these four suspected men which we

sent unto him and examined them so straightly, and threatened them in such sort, that they

confessed, there was a banished prince with 40 men, 3 days journey forward, who lay in wait to

destroy us, if he could, and that they themselves were of his company.

[pp. 466-467]

The soltan therefore understanding, that the thieves were not many, appointed us 80 men well

armed with a captain to go with us, and conduct us in our way. And the soltan himself returned

back again, taking the four thieves with him. These soldiers traveled with us two days,

consuming much of our victuals. And the 3rd day in the morning very early they set out before

our caravan, and having ranged the wilderness for the space of four hours, they met us, coming

towards us as fast as their horse[s] could run, and declared that they had found the tract of horses

not far from us, perceiving well that we should meet with enemies, and therefor willed us to

appoint ourselves for them, and asked us what we would give them to conduct us further, or else

they would return. To whom we offered as we through good, but they refused our offer, and

would have more, and so we not agreeing they departed from us, and went back to their soltan,

who (as we conjectured) was privy to the conspiracy. But they being gone, certain Tartars of our

company called holy men, (because they had been at Mecka) caused the whole caravan to stay,

and would make their prayers, and divine how we should prosper in our journey and whether we

should meet with any ill company or no? To which, our whole caravan did agree. And they took

certain sheep and killed them, and took the blade bones of the same, and first sawed them, and

them burnt them, and took of the blood of the said sheep, and mingled it with the powder of the

said bones, and wrote certain characters with the said blood, using many other ceremonies and

words, and by the same divined and found, that we should meet with enemies and thieves (to our

great trouble) but should overcome them, to which sorcery, I and my company gave no credit,

but we found it true: for within 3 hours after that the soldiers departed from us, which was the

15th day of December, in the morning, we escried far off divers horsemen which made towards

us, and we (perceiving them to be rovers) gathered ourselves together, being 40 of us well

appointed, and able to fight, and we made our prayers together every one after his law,

professing to live and die one with another, and so prepared ourselves. When the thieves were

nigh unto us, we perceived them to be in number 37 men well armed, and appointed with bows,

arrows and swords, and the captain a prince banished from his country. They willed us to yield

ourselves, or else to be slain, but we defied them, wherewith they shot at us all at once, and we at

them very hotly, and so continued our fight from morning until two hours within night, divers

men, horses and camels being wounded and slain on both parts: and had it not been for 4

handguns which I and my company had and used, we [would have] been overcome and

destroyed: for the thieves were better armed, and were also better archers then we; but after we

had slain divers of their men and horses with our guns, they durst not approach so nigh, which

caused them to come to a truce with us until the next morning, which we accepted, and

encamped ourselves upon a hill, and made the fashion of [a] castle, walling it about with packs

of wares, and laid our horses and camels within the same to save them from the shot of arrows:

and the thieves also encamped within an arrow shot of us, but they were betwixt us and the

water, which was to out great discomfort, because neither we nor our camels had drunk in 2

days.

[pp. 467-469]

Thus keeping good watch, when half the night was spent, the prince of the thieves sent a

messenger half way unto us, requiring to talk with our captain, in their tongue, the caravan basha,

who answered the messenger, I will not depart from my company to go into the half way to talk

with thee: but if that thy prince with all his company will swear by our law to keep the truce,

then will I send a man to talk with thee, or else not. Which the prince understanding as well

himself as his company, swore so loud that we might all hear. And then we sent one of our

company (reputed a holy man) to talk with the same messenger. The message was pronounced

aloud in this order: Our prince demandeth of the caravan basha, and of all you that be

bussarmans (that is to say circumcised) not desiring your bloods, that you deliver into his hands

as many caphars, that is, unbelievers (meaning us the Christians) as are among you with their

goods, and in so doing, he will suffer you to depart with your goods in quietness, and on the

contrary, you shall be handled with no less cruelty then the caphars, if he overcome you, as he

doubteth not. To the which our caravan basha answered, that he had no Christians in his

company, nor other strangers, but two Turks which were of their law, and although he had, he

would rather die then deliver them, and that we were not afraid of his threatenings, and that

should he know when day appeared. And so passing in talk, the thieves (contrary to their oath)

carried our holy man away to their prince, crying with a loud voice in token of victory, Ollo,

ollo. Where with we were much discomforted, fearing that that holy man would betray us: but

he being cruelly handled and much examined, would not to death confess any thing which was to

us prejudicial, neither touching us, nor yet what men they had slain and wounded of ours the day

before. When the night was spent, in the morning we prepared our selves to battle again: which

the thieves perceiving, required to fall to agreement & asked much of us: and to be brief, the

most part of our company being loath to go to battle again, and having little to loose, & safe-

conduct to pass, we were compelled to agree, and to give the thieves 20 ninths (that is to say) 20

times 9 several things, and a camel to carry away the same, which being received, the thieves

departed into the wilderness to their old habitation, and we went on our way forward. And that

night came to the river Oxus, where we refreshed our selves, having been 3 days without water

and drink, and tarried there all the next day, making merry with our slain horses and camels, and

then departed from that place, & for fear of meeting with the said thieves again or such like, we

left the high way which went along the said river, and passed through a wilderness of sand,

traveled 4 days in the same before we came to water: and then came to a well, the water being

very brackish, and we then as before were in need of water, and of other victuals, being forced to

kill our horses and camels to eat.

[pp. 469-472]

In this wilderness also we had almost fallen into the hands of thieves: for one night being at rest,

there came certain scouts, and carried away certain of our men which lay a little separated from

the caravan, wherewith there was a great shout and cry, and we immediately laded our camels,

and departed being about midnight and very dark, and drove sore till we came to the river Oxus

again, and then we feared nothing being walled with the said river: & whether it was for that we

had gotten the water, or for that the same thieves were far from us when the scouts discovered us,

we know not, but we escaped that danger.

THE CITY OF BUKHARA

So upon the 23rd day of December we arrived at the city of Boghar [=Bukhara] in the land of Bactria. This

Boghar is situated in the lowest part of all the land, walled about with a high wall of earth, with

divers gates into the same: it is divided into 3 partitions, whereof two parts are the kingís, and the

3rd part is for the merchants and markets, and every science hath their dwelling and market by

themselves. The city is very great, and the houses for the most part of earth, but there are also

many houses, temples and monuments of store sumptuously built, and gilt, and specially

bathstoves so artificially built, that the like thereof is not in the world: the manner where of is too

long to rehearse. There is a little river running through the midst of the said city, but the water

thereof is most unwholesome, for it breedeth sometimes in men that drink thereof, and especially

in them that be not there born, a worm of an ell long, which lieth commonly in the leg betwixt

the flesh and the skin, and is plucked out about the ankle with great art and cunning, the surgeons

being much practiced there, and if she break in plucking out, the party dieth, and every day she

commeth out about an inch, which is rolled up, and so worketh till she be all out. And yet it is

there forbidden to drink any other thing then water, & mares milk, and whosoever is found to

break that law is whipped and beaten most cruelly through the open markets, and there are

officers appointed for the same, who have authority to go into any manís house, to search if he

have either aquavitae, wine, or brage, and finding the same, do break the vessels, spoil the drink,

and punish the masters of the house most cruelly, yea, and many times if they perceive but by the

breath of a man that he hath drunk, without further examination he shall not escape their hands.

There is a metropolitan in this Boghar, who causeth this law to be so straightly kept: and he is

more obeyed then the king, and will depose the king, and place another at his will and pleasure,

as he did by this king that reigned at our being there, and his predecessor, by the means of the

said metropolitan: for he betrayed him, and in the night slew him in his chamber, who was a

prince that loved all Christians well.

This country of Boghar was sometime subject to the Persians, & do now speak the Persian

tongue, but yet now it is a kingdom of itself, and hath most cruel wars continually with the said

Persians about their religion, although they be all Mahometists. One occasion of their wars is,

for that the Persians will not cut the hair of their upper lips, as the Bogharians and all other

Tartars do, which they accompt great sin, and call them caphars, that is, unbelievers, as they do

the Christians.

The king of Boghar hath no great power or riches, his revenues are but small and he is most

maintained by the city: for he taketh the tenth penny of all things that are there sold, as well by

the craftsmen as by the merchants, to the great impoverishment of the people, whom he keepeth

in great subjection, and when he lacketh money, he sendeth his officers to the shops of the said

merchants to take their wares to pay his debts, and will have credit of force, as the like he did to

pay me certain money that he owed me for 19 pieces of kersey. Their money is silver and

copper, for gold there is none current: they have but one piece of silver, & that is worth 12 pence

English, and the copper money are called Pooles, and 120 of them goeth the value of the said 12

pence, and is more common payment then the silver, which the king causeth to rise and fall to his

most advantage every other month, and sometimes twice a month, not caring to oppress his

people, for that he looketh not to reign above 2 or 3 years before he be either slain or driven

away, to the great destruction of the country and merchants.

The 26th day of the month I was commanded to come before the said king, to whom I presented

the Emperor of Russia his letters, who entertained us most gently, and caused us to eat in his

presence, and divers times he sent for me, and devised with me familiarly in his secret chamber,

as well of the power of the Emperor, and the Great Turk, as also of our countries, laws, and

religion, and caused us to shoot in handguns before him, and did himself practice the use thereof.

But after all this great entertainment before my departure he showed himself a very Tartar: for he

went to the wars owing me money, and saw me not paid before his departure. And although

indeed he gave order for the same, yet was I very ill satisfied, and forced to rebate part, and to

take wares as payment for the rest contrary to my expectation: but of a beggar better payment I

could not have, and glad I was so to be paid and dispatched.

But yet I must needs praise and commend this barbarous king, who immediately after my arrival

at Boghar, having understood our trouble with the thieves, sent 100 men well armed, and gave

them great charge not to return before they had either slain or taken the said thieves. Who

according to their commission ranged the wilderness in such sort, that they met with the said

company of thieves, and slew part, and part fled, and four they took and brought unto the king,

and two of them were sore wounded in our skirmish with our guns: And after the king had sent

for me to come to them, he caused them all 4 to be hanged at his palace gate, because they were

gentlemen, to the example of others. And of such goods as were gotten again, I had part restored

me, and this good justice I found at his hands.

[pp. 472-474]

THE BUKHARAN MERCHANT FAIR

There is yearly great resort of merchants to this city of Boghar, which travel in great caravans

from the countries thereabout adjoining, as India, Persia, Balgh [=Balkh], Russia, with divers

others, and in times past from Cathay, when there was passage: but these merchants are so

beggarly and poor, and bring so little quantity of wares lying two or three years to sell the same,

that there is no hope of any good trade there to be had worthy the following.

The chief commodities that are brought thither out of these aforesaid countries, are these

following.

The Indians do bring fine whites, which the Tartars do all roll about their heads, & all other kinds

of whites, which serve for apparel made of cotton wool and crasko, but gold, silver, precious

stones, and spices they bring none. I inquired and perceived that all such trade passeth to the

Ocean sea, and the veins where all such things are gotten are in the subjection of the Portingals

[=Portuguese]. The Indians carry from Boghar again wrought silks, red hides, slaves, and

horses, with such like, but of kersies and other cloth, they make little accompt. I offered to barter

with merchants of those countries, which came from the furthest parts of India, even from the

country of Bengala, & the river Ganges, to give them kersies for their commodities, but they

would not barter for such commodity as cloth.

The Persians do bring thither craska, woolen cloth, linen cloth, divers kinds of wrought pied

silks, argomacks, with such like, and do carry from thence red hides with other Russe wares, and

slaves, which are of divers countries, but cloth they will buy none, for that they bring thither

themselves, and is brought unto them as I have inquired from Aleppo in Syria, and the parts of

Turkey. They Russes do carry unto Boghar, red hides, sheepskins, woolen cloth of divers sorts,

wooden vessels, bridles, saddles, with such like, and do carry away from thence divers kinds of

wares made of cotton wool, divers kinds of silks, crasca, with other things, but there is but small

utterance. From the countries of Cathay are brought thither in time of peace, and when the way

is open, musk, rhubarb, satin, damask, with divers other things. At my being at Boghar, there

came caravans out of all these aforesaid countries, except from Cathay: and the cause why there

came none from thence was the great wars that had dured 3 years before my coming thither, and

yet dured betwixt 2 great countries & cities of Tartars, that are directly in the way betwixt the

said Boghar and the said Cathay, and certain barbarous field people, as well Gentiles and

Mahometists bordering to the said cities. The cities are called Taskent [=Tashkent] and Caskar

[=Kashgar], and the people that war against Taskent are called Cassaks of the law of Mahomet:

and they which war with the said country of Caskar are called Kings, Gentiles, & idolaters.

These 2 barbarous nations are of great force living in the fields without house or town, & have

almost subdued the aforesaid cities, & so stopped up the way, that it is impossible for any

caravan to pass unspoiled: so that 3 years before our being there, no caravan had gone, or used

trade betwixt the countries of Cathay and Boghar, and when the way is clear, it is 9 months

journey. To speak of the said country of Cathay, and of such news as I have heard thereof, I have though

it best to reserve it to our meeting.

[pp. 474-475]

RETURN VOYAGE: BUKHARA TO URGENCE

I having made my solace at Boghar in the winter time, and

having learned by much inquisition, the trade thereof, as also of all the other countries thereto

adjoining, and the time of the year being come, for all caravans to depart, and also the king being

gone to the wars, and news come that he was fled, and I advertised by the metropolitan himself,

that I should depart, because the town was like to be besieged: I though it good and meet, to take

my journey some way, and determined to have gone from thence into Persia, and to have seen

the trade of that country, although I had informed myself sufficiently thereof, as well as

Astrakhan, as at Boghar: and perceived well the trades not to be much unlike the trades of

Tartaria: but when I should have taken my journey that way, it was let by divers occasions: the

one was, the great wars that did newly begin betwixt the Sophie [=king of Persia], and the kings

of Tartaria, whereby the ways were destroyed: and there was a caravan destroyed with rovers &

thieves, which came out of India and Persia, by safe conduct: and about ten days journey from

Boghar, they were robbed, and a great part slain. Also the metropolitan of Boghar, who is

greater then the king, took the Emperors letters of Russia from me, without which I should have

been taken slave in every place: also all such wares as I had received in barter for cloth, and as I

took perforce of the kind, & other his nobles, in payment of money due unto me, were not

vendible in Persia: for which causes, and divers others, I was constrained to come back again to

Mare Caspium, the same way I went: so that the eighth of March 1559, we departed out of the

said city of Boghar, being a caravan of 600 camels: and if we had not departed when we did, I

and my company had been in danger to have lost life and goods. For ten days after our

departure, the king of Samarcand came with an army, & besieged the said city of Boghar, the

king being absent, and gone to the wars against another prince, his kinsman, as the like chanceth

in those countries once in two or three years. For it is [a] marvel, if a king reign there above

three or four years, to the great destruction of the country, and merchants.

The 25th of March, we came to the aforesaid town of Urgence, and escaped the danger of 400

rovers, which lay in wait for us back again, being the most of them kindred to that company of

thieves, which we met with going forth, as we perceived by four spies, which were taken. There

were in my company, and committed to my charge, two ambassadors, the one from the king of

Boghar, the other from the king of Balgh, and were sent unto the Emperor of Russia. And after

having tarried at Urgence, and the castle of Sellizure, eight days for the assembling, and making

ready of our caravan, the second of April we departed from thence, having four more

ambassadors in our company, sent from the king of Urgence, and other soltans, his brethren, unto

the Emperor of Russia, with answer of such letters as I brought them: and the same ambassadors

were also committed unto my charge by the said kings and princes: to whom I promised most

faithfully, and swore by our law, that they should be well used in safety, according as the

Emperor had written also in his letters: for they somewhat doubted, because there had none gone

out of Tartaria into Russia, of long time before.

[pp. 475-477]

A CASPIAN STORM

The 23rd of April, we arrived at the Mare Caspium again, where we found our bark which we

came in, but neither anchor, cable, cock, nor sail: nevertheless we brought hemp with us, and

spun a cable ourselves, with the rest of our tack, and made us a sail of cloth of cotton wool, and

rigged our bark as well as we could, but boat or anchor we had none. In the mean time being

devised to make an anchor of wood of a cart wheel, there arrived a bark, which came from

Astracan, with Tartars and Russes, which had two anchors, with whom I agreed for the one: and

thus being in a readiness, we set sail and departed, I, and the two Johnsons begin master and

marines ourselves, having in our bark the said six ambassadors, and 25 Russes, which had been

slaves a long time in Tartaria, nor ever had before my coming, liberty, or means to get home, and

these slaves served to row when need was. Thus sailing sometimes along the coast, and

sometimes out of the sight of land, the 13th day of May, having a contrary wind, we came to an

anchor, being three leagues from the shore, & there rose a sore storm, which continued 44 hours,

and our cable being of our own spinning, brake, and lost our anchor, and being off a lee shore,

and having no boat to help us, we hoisted our sail, and bare roomer with the said shore, looking

for present death: but as God provided for us, we ran into a creek full of ooze, and so saved

ourselves with our bark, & lived in great discomfort for a time. For although we should have

escaped with our lives the danger of the sea, yet if our bark had perished, we knew we should

have been, either destroyed, or taken slaves by the people of that country, who live wildly in the

field, like beasts, without house or habitation. Thus when the storm was ceased, we went out of

the creek again: and having set the land with our compass, and taken certain marks of the same,

during the time of the tempest, whilest we rid at our anchor, we went directly to the place where

we rid, with our bark again, and found our anchor which we lost: whereat the Tartars much

marveled how we did it. While we were in the creek, we made an anchor of wood of cart

wheels, which we had in our bark, which we threw away, when we had found our iron anchor

again. Within two days after, there arose another great storm, at the northeast, and we lay atry,

being driven far into the sea, and had much ado to keep our bark from sinking, the billow was so

great: but at the last, having fair weather, we took the sun, and knowing how the land lay from

us, we fell with the river Iaic, according to our desire, whereof the Tartars were very glad,

fearing that we should have been driven to the coast of Persia, whose people were unto them

great enemies.

[pp. 477-479]

Note, that during the time of our navigations, we set up the red cross of St. George in our flags,

for honor of the Christians, which I suppose was never seen in the Caspian Sea before. We

passed in this voyage divers fortunes: notwithstanding the 28th of May we arrived in safety at

Astracan, and there remained till the tenth of June following, as well to prepare us small boats, to

go up against the stream of the Volga, with our goods, as also for the company of the

ambassadors of Tartary, committed unto me, to be brought to the presence of the Emperor of

Russia.

During the middle ages, European merchants successfully traded in Eurasia and even reached

the rich and fabled land of Cathay (China) thanks to the relatively peaceful climate created by

the Pax Mongolica. But when the Mongol Empire

disintegrated instability made the old overland routes increasingly dangerous and often impassable.

Nonetheless, in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries European

entrepreneurs, still very much familiar with the writings of such merchant-travelers as Marco

Polo (who praised the wealth and grandeur of the lands of the Great Khan) were still lured

by the wealth of the Far East. In the end of the fifteenth century, explorers such as

Christopher Columbus, Amerigo Vespucci, and Vasco da Gama all attempted to find routes to

China, whether circumnavigating the globe westward, or sailing southeast, around Africaís Cape

of Good Hope. Another route, which often receives less attention, was the hypothesized

Northeast passage: accessing the east by sailing around the northern confines of Asia.

And the 22nd we came unto a castle called Vasiliagorod [=Vasil'gorod], distant

25 leagues, which we left upon our right hand. This town or castle had his name of this

Emperorís father, who was called Vasilius, and gorod in the Russe tongue is as much to say as a

castle, so that Vasiligorod is to say, Vasiliusí castle: and it was the furthest place that the said

Emperor conquered from the Tartars. But this present Emperor his son, called Ivan Vasilivitch,

hath had great good success in his wars, both against the Christians and also the Mahometists

[=Muslims] and Gentiles, but especially against the Tartars, enlarging his empire even to the

Caspian Sea, having conquered the famous river of Volga, with all the countries thereabout

adjacent. Thus proceeding on our journey the 25th day of May aforesaid, we came to another

castle called Sabowshare [=Cheboksary], which we left on our right hand, distant from Vasiligorod 16 leagues.

The country hereabout is called Mordovits, and the habitants did profess the law of the Gentiles:

but now being conquered by this Emperor of Russia, most of them are

Christened, but lie in the woods and wilderness, without town or habitation.

Murom

Nizhnii Novgorod

Kazan

Tartars

Astrakhan