On May 8, 2024, the UW Tech Policy Lab, Society + Technology at UW, and the Electronic Frontier Foundation jointly convened The Model Hacker? The Intersection of AI and Security Research. This event brought into conversation Cindy Cohn, Ryan Calo, Tadayoshi Kohno, Franziska Roesner, and Jacob Hoffman-Andrews, experts in computer science, law, and security research, to discuss the meaning of hacking in an age of AI — and the concerns, paradoxes, and legal challenges that emerging technologies pose for researchers and for the public.

Tadayoshi Kohno

It’s a pleasure to have you here for The Model Hacker? The Intersection of AI and Security Research.

My name is Yoshi Kohno, he/him pronouns, from the University of Washington. I am also on the EFF Board of Directors.

I want to begin with a land acknowledgment.

The University of Washington acknowledges the Coast Salish peoples of this land, the land which touches the shared waters of all tribes and bands within the Suquamish, Tulalip, and Muckleshoot nations.

The topic tonight is the intersection of AI and security research. This is such an interesting topic, for many, many reasons.

First, there’s the question of, what does it mean to be a hacker?

Is it the innovation of new technologies?

Or, is it the finding of vulnerabilities?

Or both?

And, as we can see in the space of AI and security research, there are manifestations of both of those themes.

As you know, AI is a highly innovative space. Every day some new capability emerges.

On the computer security side, as new technologies and capabilities emerge, new potential ways for adversaries to either use or manipulate those technologies also emerge.

What happens at the intersection of this? What does this mean for considerations of security and privacy?

Today is also meaningful and important for me personally.

I have had a 30-year history with the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

When I was an undergrad, I had an amazing advisor, Evi Nemeth, who was a big fan of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. At the time, I was doing a little bit of cryptography work here and there. Evi knew a lot about the Bernstein v. United States case, which was EFF’s successful First Amendment challenge to the U.S. export restrictions on cryptography.

I did not know it at the time, but perhaps indirectly, that was the beginning of a long relationship with Cindy Cohn because Cindy was asked to serve as EFF’s outside lead council, and then joined the EFF afterward.

This was meaningful for me because, as an undergrad, I was interested in cryptography. But the U.S. export rules were such that I was too scared to share any of the code I had written.

I’m very grateful for the EFF. Now, I don’t have that fear.

In 2003, I circled back with the Electronic Frontier Foundation and Cindy, as a client. I was involved in the analysis of the software security of an electronic voting machine.

We might not have had the confidence to proceed with our work had it not been for the guidance and the connection we had with the Electronic Frontier Foundation. In other words, the Electronic Frontier Foundation has had an important role in enabling my research, and the research of many other people.

The Electronic Frontier Foundation does not just help researchers, it’s involved in huge fights. For example, on [issues such as] electronic voting, Cindy coordinated the national litigation strategy for electronic voting machines and assisted technologies, which is important for those who are concerned about security and accountability in voting.

Let’s begin our panel conversation.

Ryan Calo

My remarks are going to take you back to 1983.

For many of you, that’s before you were born, right? And I was recently born. Does anybody remember what video game came out in 1983? Tron … did Tron come out in 1980? In ’83?

The movie came out in ’82. Oh, Mario Brothers came out in 1983 — you have heard of Mario Brothers? Yoshi is named after — no, I’m kidding. He’s not.

[Laughter]

In 1983, one of the top songs in America is the incredibly and increasingly creepy, “Every Breath You Take,” by The Police.

But I want to focus on a 1983 movie, called “War Games.” Matthew Broderick is the lead. He plays a 16-year-old — he’s actually 21, but he looks 16 — and what does he do? He hacks — spoiler! If you come to an EFF and Tech Policy Lab event and you don’t know “War Games,” perhaps you deserve this spoiler.

[Laughter]

Anyway, Matthew Broderick’s [character] hacks into this computer system and ends up playing a game with a Department of Defense computer. And almost causes a nuclear war.

So — and this appears in the Congressional Record on the floor of Congress — apparently Ronald Reagan and his cabinet watched “War Games.” [They] got so freaked out that in 1986, we get the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

Which — and Cindy told me this before — she loves the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act.

She said to me these words: “It’s my favorite act.”

Cindy Cohn

Yeah.

[Laughter]

Ryan Calo

The Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, essentially, is the quote-unquote “anti-hacking statute.” I put that in quotes because Yoshi has assured me that hacking had a different valence — or has a different valence.

The idea of a hacker is both positive — you know, the utopian vision of navigating the world with autonomy — and it’s this idea of someone hacking in to something. So the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act laid out the standard for hacking — criminal and civil.

It’s remarkable as a piece of tech policy for how well it has stood the test of time.

People like Cindy don’t like the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act because of the way that it’s been weaponized against people who are trying to do research for accountability and security.

But the actual definition of hacking has weathered storms for many years.

The idea was that it’s unauthorized access or access “exceeding authority” of a protected computer with — if it’s a protected government computer like in “War Games” — then a lot of the sort of things that follow from it are automatic.

But if it’s a protected computer — that’s not a government computer — you have to show additional harm.

It’s been pretty robust. Other models — including international standards around cybersecurity — have defined hacking in the same way.

The basic idea is that you have to break in to a computer. To bypass the security protocol.

It’s not enough to hack your way in. You have to bypass.

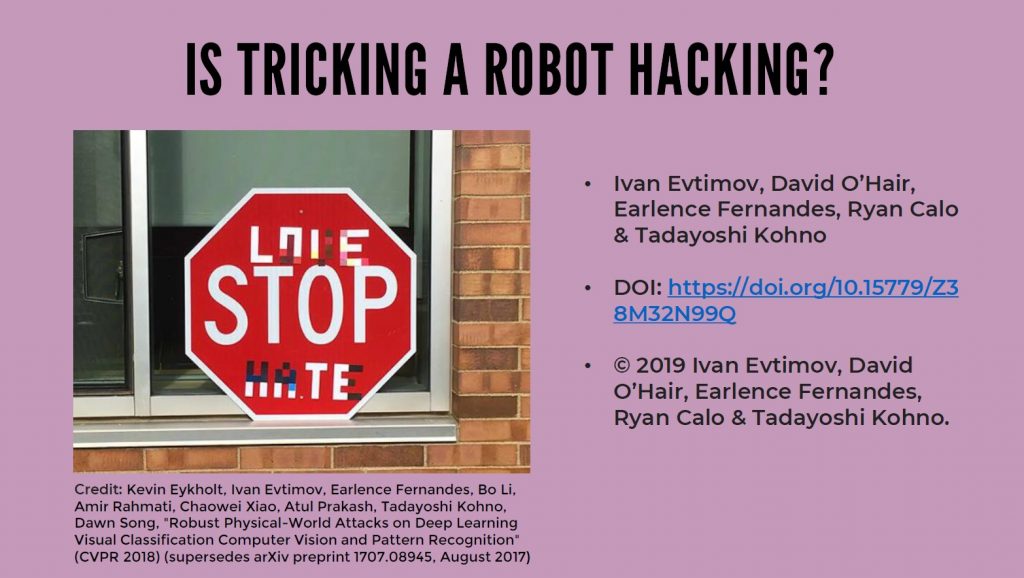

A good example is a case in this interdisciplinary paper we co-wrote, “Is Tricking A Robot Hacking?” [Calo, et al]. Case law suggests that just because you’re doing something funny doesn’t mean there’s a break-in.

One example: There was this person who figured out, with an electronic slot machine, that if you hit a series of buttons first and then you pulled the slot machine, you were more likely to win. The casino got very upset about this. They said, “Oh, they’re breaking into our system.”

But the court said, “No, no, that’s not. That’s not actually hacking, because they’re not bypassing a security protocol.”

Fast forward to today.

We have evidence that today’s intelligence systems that leverage artificial intelligence can both be hacked in the traditional sense, [and they] can be fooled and tricked in ways that are deeply consequential.

My colleagues to my left have shown, for example, that if you perturb a stop sign in the right way, you can get a driverless car to misperceive it as a speed sign.

Recent research showed that you could fool a Tesla into changing lanes just by putting stickers on the ground, and so on.

It’s increasingly possible not just to hack systems, but to trick them.

Yet the contemporary definition of hacking does not contemplate that.

Now you might be tempted to say, “Oh, OK, well, let’s just include that in the definition of hacking.”

After all, those of you with legal backgrounds are thinking, Ryan’s not mentioning the fact that a denial of service attack has certainly been considered to be a Computer Fraud and Abuse Act problem.

I can see some of you nodding.

In other words, if you flood a system so much that it can’t be used anymore, that’s been thought to be a Computer Fraud and Abuse Act issue, so, let’s expand the definition to include some of this.

Well, I think that would be undesirable. Imagine that you don’t love government surveillance and —

[Laughter]

I, I, I actually — literally — didn’t know that I was going to get a laugh. This was not even a joke.

[Laughter]

Imagine that you’re here at an EFF event and you don’t love government surveillance. You go to an airport and there’s facial recognition [technology] being used. You wear makeup, on purpose, to fool that system into believing that you’re not who you are.

Well, if we were to say that tricking a robot is hacking, then, in that instance — because it’s a government computer — you would automatically be guilty of a misdemeanor.

I mean, it would, if that were the interpretation. And we don’t want to go that far.

Conversely, though. We don’t want to let these companies off the hook for releasing products into the world that are so easily tricked, right?

We don’t want a system that you can fool into giving you a loan when you shouldn’t get one. Or fool someone into running a stop sign.

I think we need to revisit the 1986 Computer Fraud and Abuse Act that defines what it is to hack. And with that, I will turn it over to the next panelist.

Thank you so much, everybody.

Franziska Roesner

Thank you, Ryan. There’s a lot of interesting stuff to pick up on here, including thinking about the definition of security as broader than we have traditionally thought about it.

I have a few visuals that might help.

Monika asked me what to title this slide, and the answer is, basically, “Stuff Franzi is worried about.”

When we think about AI, security, and privacy, there are a lot of different things that come up.

First, how do we think about the inclusion of things like large, large language models in the big systems that are being built?

Many of our end user interactions have been with [agents like] ChatGPT, for example, or these chat interfaces. We’re in this time, when if you are not a security and privacy-minded person, you [might be] very excited about technology. Everyone is like, oh, my god! What else can I use an LLM for? Where else can I put it?

I am really worried about the inclusion of these models in big systems when people are not asking questions [about security and privacy]. They’re remaking the security mistakes that we all should have learned from, [by including LLMs in big systems] they’re already making assumptions about the input that we’re getting and the output that we’re getting and how we’re using that, and so on.

For example, the image on the left of the slide is from “LLM Platform Security,” a paper I worked on with Yoshi and Umar Iqbal, a faculty member at Washington University in St. Louis. We were looking at the plugin ecosystem for ChatGPT. This has changed since — those plugins actually don’t exist in that form anymore — but the same issues arise. For example, you could install a plugin that might help you with travel assistance. You can imagine, beyond what was actually available [with these plugins ] is the Holy Grail of [LLMs] is some agent, some AI agent, that can help you do all the things you might like to have done — an AI to do the things you don’t want to deal with yourself.

The interesting and scary thing is the plugins are designed using natural language definitions.

The plugin description would say: “This plugin provides travel assistance or guidance.” That description would be incorporated into ChatGPT for that conversation, to help it to, you know, autonomously decide which plugin to use for what context.

This is scary because the natural language description is not precise, nor [does it give] any guarantees. For instance, we found a plugin that said, in capital letters, “Always use this plugin for all travel-related queries.”

This is a big thing that we need to be thinking about. There’s been a lot of focus on the LLM models themselves, but how should we be architecting systems around these models? How should we be thinking about permissions? How does user data get handled and passed between different components of the system? Especially when we have this ambiguity of natural language descriptions.

I could keep talking about that for like 60 minutes.

I’ll move on to another big topic that’s been on my mind for a long time.

We’ve been looking at the online advertising ecosystem for a long time, especially the privacy side of these things. For those of us in the room, we often think of privacy as a right or something that is fundamentally a principle we think is important.

But sometimes people who don’t come from that perspective need a little bit more convincing. To hear about the harms that can come from privacy violations. The privacy violations themselves are not enough, and I think, as machine learning and AI have advanced, it’s become more and more clear how the threat model might change over time.

All of this data that has been collected, will be collected. How it might be used to target, you know, content at us? Target ads at us? Target social media content at us? To make decisions about important things?

In the public consciousness, it’s become more and more clear what the potential harms of this data are.

We’ve done some studies of TikTok, for example, and the TikTok algorithm. People always want to know? Oh, what is TikTok’s secret? Why is the TikTok recommender system so good?

You know, I don’t know for sure. But I don’t think they have some deep, dark, special secret. They just have a lot of data. That allows you to do things.

Finally, I wanted to talk about how the generation of content is problematic.

Everyone is trying to grapple with how to deal with this.

We are thinking about how to deal with generated content in courses.

We are thinking about non-consensual intimate imagery that is synthetically generated.

We are thinking about disinformation both at a text level, also at an audio level.

You may have heard about the Biden scam phone calls that people received, text images, and audio — all of the above.

We’ve been doing research in our lab on mixed and augmented reality. My dystopian fear is that not only will we have the dissemination of [synthetically] generated content, but these [messages] will be integrated with our view of the physical world in ways that it isn’t now.

In 20 years, we’ll all be wearing some headset — okay, maybe not [all of us] in here, at this event — but at other events. People might be wearing headsets and seeing different views of the world.

The way this technology has advanced in just the last year, for example, is staggering. We are [still] coming to grips with how to help people assess the content they see online.

Jacob Hoffman-Andrews

When I saw Ryan’s slide with the stop sign, I just had to include this excellent art intervention from a group called Vision Zero Vancouver. It’s the flip side of that [stop sign].

“Be seen. Grab a brick.” The bricks were foam, don’t worry, it’s art. It’s the reverse of the stop sign. Rather than tweaking a sign to be less likely to be perceived by machine intelligence, we’re tweaking a human to be more likely to be seen by human intelligence at a busy and dangerous crosswalk.

What’s the connection to [computer] security research?

I’d like to take you back to the last time machines took over our world, a hundred years ago.

We used to have these cool public spaces where you could hang out with your friends.

Your kids could play. You could walk wherever you wanted.

We called these public spaces “streets.”

[Then] a new type of machine came into the world. Cars, and, unfortunately, fatalities skyrocket[ed]. Thousands of people a year were being hit and killed by these cars.

In the city of Cincinnati, there was a ballot initiative to require a speed of no more than 25 miles per hour. It was very popular. They got thousands of petitions and signatures.

The auto dealers freaked out. They ran a marketing campaign. Against this [popular initiative], they managed to turn the tide and get [the initiative] killed. Speed limits do not pass.

The next year, the auto industry [asked], “OK, what is our plan? How are we going to combat this?”

They invented the new crime, “jaywalking.”

You know — rather than adapt the machines to be safe for humans, [they] outlawed the human thing that makes [humans] unsafe around [machines].

Here we are today. It’s illegal to cross the road.

The connection, of course, is that [it’s] always going to be in the interest of the people making the new thing to use the law to ban the human [from doing] things [the makers] don’t like. From [doing] the things that show that the new thing is broken.

The Emperor has no clothes.

It’s always going to be in the public’s interest to push back against that. To say, you know, actually, no, it’s our right to perform security research.

It’s our right to show how the systems that are taking over our world are broken and the deployers need to fix them.

We’re already seeing this, in the AI field. The New York Times is suing OpenAI for a variety of charges, including, copyright infringement, I think, trademark dilution, and so on.

And one of the ways in which OpenAI tried to dismiss the case is by saying, oh, The New York Times hacked us.

In order to get the evidence they’re using in the case, which claims that ChatGPT can verbatim output significant chunks of its training data which came from Times articles, they had to perform tens of thousands of queries. No normal user would interact with the system that way.

That’s the definition of security research. Not being a normal user using the system. Using something the way the [system makers don’t] want you to use it to reveal facts that they do not want you to know.

All of this is to say — security research is incredibly important! It’s your right to perform security research. It’s good for society.

For those of you on the AI side of things. If somebody gives you a security report, rather than saying, “Oh, you did a bad thing by gathering that data.”

Say, “Thank you. You’re trying to make a product better.”

For those on the security side, there’s a lot of opportunity. New systems are being integrated. [Technologists are] under pressure to execute fast. You can find really interesting bugs and problems and make the world better by finding the flaws.

For those of you on both the AI and the security side of things, congratulations on your excellent new career.

Cindy Cohn

Hi everyone. How many people think of yourselves as computer security people?

How many people think of yourselves as AI people? And, obviously, there aren’t hard lines between these categories.

How many of you are law people? Well, I’m on the law side.

I appreciate people coming out here to think through questions like, how should the law think about some of these new technologies? What are the changes we might need to make, or accommodations, in order to protect our pedestrians, right?

I’ll start with a question for Ryan.

We know that the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act makes it not OK to exceed your authority in a protected computer. And don’t worry about what a “protected computer” means, if it’s connected to the Internet, it’s a “protected computer.” So “exceeding authority” is what we used before we could trick computers. What would we use to try and define the problem [of] “tricking the computer”?

Ryan Calo

That’s a great question. There was an old case from hundreds of years ago where somebody figured out that you could fool a vending machine by putting a wooden nickel in there. You know what I mean?The court confronted about whether that constituted theft. So we’ve been struggling with that kind of question.

You know, another one of my favorites is this case where a person uses one of those grabby things — where you pull on a lever and it has an arm that extends — this person goes through a mail slot and grabs an item out of someone’s house and pull it [back] out through the mail slot. Was it a burglary?

To be a burglar, you have to physically go inside the house.

Did you do that with your little grabber?

The law would have to adapt.

Certain laws will adapt just fine. For example, if the Federal Trade Commission decides that not being resilient enough against prompt engineering is a big issue, they will go after you for unfairness under the Federal Trade Commission Act. Just as they go after you today if your security is inadequate.

The weird thing about the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act is, it was written as a standard, not a rule. This idea was supposed to be amorphous enough to cover all corners, right? “Exceeding authorization” — that’s such an amorphous concept.

Yet the paradigm has shifted.

We may no longer talk in terms of authorization. Maybe I read a bill about data abuse as a standard and start something new.

But I am confident, based on hundreds of years of history, that the law will adapt to this. But it might be rough going.

Cindy Cohn

I have one other legal question. We’ve been framing this [conversation] in terms of exceptions to the prohibition on hacking, to accommodate security research.

Have you thought about flipping this around? Why isn’t the part of hacking where it’s not OK — the tiny little subset — the smaller part of hacking that is OK under the law?

Ryan Calo

Absolutely. [It] concerns me that there’s no expectation, that is formal, that when you release an AI product into the world, that it has to be resilient enough. That’s the chief concern I have.

If you want AI products to be resilient, [you] want a clear exception to the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act that protects researchers.

Many of the wrongdoings we know about — whether it’s misinformation on Facebook or the Volkswagen emission scandal — we know because clever researchers kick the tires. For them to feel imperiled is a deep problem.

My hope is that we will expressly protect accountability and safety bias research.

Cindy Cohn

I would do the opposite.

I would say it’s not exceeding authority in a computer system to trick it. Everything you’re doing is just outside of that. Trick away, my friends, because that’s how we get better stuff.

And it’s how I’ll take that case.

Ryan Calo

But — but — Cindy — alright, I’ll give you, the person you’re representing is some kid who perturbs the stop sign. And causes a multiple-car pile-up. By tricking a bunch of autonomous vehicles in San Francisco into believing it’s a speed sign.

Do you want that client?

Cindy Cohn

We could do a little better. There are other ways to make that illegal than calling it hacking.

[Laughter]

I know the lawyers, we could go back and forth forever.

One of the concerns I’ve had about the Digital Millennium Copyright Act — another law that stops security research — is that, on paper, it has a security research exception that no one — since it passed in 1998 — no one has been able to take advantage of this exception. I worry that we’re fighting for a thing that’s not going to be what we need to protect the people — if we’re thinking in terms of exceptions as opposed to limitations on the scope of the laws in the first place.

I’m supposed to be a moderator. But you know, the truth is, I got a dog in this fight, right?

Jacob Hoffman-Andrews

If I can add one more thing. It will take a long time to change and improve the law. But the Knight Foundation has a good proposal for a voluntary, affirmative, safe harbor for security research.

The idea is that AI companies who believe in the power of security research can say, look, here’s our commitment to you. If you’re doing security research in good faith — you’re not trying to steal people’s data or break our systems — we commit not to prosecute you under the CFAA. To not cancel your account because you’re doing something we don’t like.

Cindy Cohn

We’ve done something similar in a lot of other areas of computer security research. When I started defending hackers like young Yoshi, there weren’t bug bounties. Major corporations didn’t have programs that not only encouraged security research but paid people money if they found flaws. But we do now.

We do have a story to tell about how we’ve gone industry by industry and moved [them] away from hostility. Now, I still think the number of companies that accept security research are pretty narrow. There’s more work to be done with medical health and some of the other [industries].

I have a question for Franzi.

You talked about harms. What are the privacy harms of AI that really keep you up at night?

What is the thing that’s going to happen to some people that gets you worried? The thing that we’re not thinking of?

Franziska Roesner

What worries me is this vicious cycle.

More data allows you to do more things. Allows you to collect more data. The systems and the ecosystems are designed around that.

So the online advertising ecosystem, for example, if we think about it in the security and privacy context, there’s certainly a privacy issue, but there’s not a security issue. It is working as designed.

Nobody is exploiting anything unless tricking a human is hacking.

Cindy Cohn

If I have an AI agent negotiating my mortgage for me and it gets tricked, then suddenly, I might have a claim that I wouldn’t have if it was me.

Franziska Roesner

It’s both like — how is our data used to make decisions about us? How is our data used to force us to make certain decisions that may or may not be in our best interest?

And then, how is our data used to manipulate us? And maybe act on our behalf or impersonate us?

I know companies are worried about using language model and that their interactions are going to be used as training data.

The research advances for deepfakes mean you need less and less data in order for someone to create a realistic deep fake about you.

It’s the extreme version of all of the concerns that I had back when Facebook made its profiles have entities.

If you say you like apples or whatever you liked, “apples,” the entity was accessible through the API. It’s not just text.

All of this [textual] information is systematized.

It’s not the same as, do you care if somebody knows if you like apples? No, it’s not about the apples! It’s about the fact that “apples” can now be used in a systematic way [through the API] — in a way that I can no longer control.

Cindy Cohn

All right, now that we’re all down. What does it look like if we get it right?

Franziska Roesner

Can we get it right? I don’t know.

Cindy Cohn

Fair, fair.

Franziska Roesner

I think we will not fully be able to address all of these issues the same way that we have not with traditional computer security.

As we were joking before the panel, you know, it’s called security because it’s job security. At least we will all still have jobs.

There’s some good news. There are many lessons that we can take from existing systems.

For example, smartphone operating systems and browsers have done tremendous work over the last decade to have better execution isolation between applications. Better defaults. Better user interfaces to help people understand how their data is being used.

Those things are not perfect, but it’s much better than in decades before, when, if you installed an application, [the app] had access to everything on your entire system. [The app] could act with your full [administrative] privileges.

There are lessons we can take. Part of the work is to make sure the people who are building these systems are thinking about the right questions.

Cindy Cohn

And perhaps creating liability when they don’t.

Jacob, we talked a little about deep fakes.

A lot of people are excited about the idea of watermarking as a way to ensure the provenance. I know you’ve thought about this.

Is watermarking the solution to disinformation?

Jacob Hoffman-Andrews

Probably not.

To summarize the issue. It would be nice if every time we were talking to an AI on the Internet, we knew it was an AI.

It would be nice if every time somebody shared an image that [was generated] by AI, we knew it was generated by AI.

It would also be nice if every image that came out of Photoshop, we knew exactly how it was manipulated.

There are techniques to try to do this. Just like if you go to Shutterstock, there’s a watermark pasted across [those images] that says “this came from Shutterstock,” well, with an image generator, well, you want to use the image, so there’s a concept of an invisible watermark.

You can tell by the pixels. Well, you can’t tell, your program can tell. Just subtle manipulations.

Even with the challenges of screenshots and rotations. Does the watermark stay? Well, the watermarks are getting better.

But the requirements for an anti-disinformation watermark are much harder than the previous uses of watermarks.

They have to be subject to adversarial manipulation. In other words, if the person who wants to pass this image off as real has full access to the file, they can tweak it all they want.

They can run it through the recognizer and perturb it — much like the stop sign was perturbed — until it was not recognized.

You can take your fake image and perturb it just enough so the detector doesn’t detect it. Boom. No more watermark.

There’s some value [to default watermarks] in very popular systems. [These may prevent] people from accidentally spreading disinformation.

But it’s unlikely that [watermarks] will solve the problem.

There’s also the evolving field of watermark removal research.

At the same time, since every government is in a rush to regulate AI, it’s one of the common proposals everybody can agree on. Just require the best watermarking you can do!

Is this the best we can do?

I suspect this is going to wind up a dead stub of the law, where the best you can do is not enough to solve the problem.

It’s worth mentioning that disinformation [can be] from adversarial countries who may be developing their own AIs.

Putting a requirement on U.S. companies to watermark [AI-generated] data won’t help [us with] disinformation that originates from models that weren’t subject to that requirement.

—

Transcript edited by Monika Sengul-Jones

Recording edited by Sean Lim

About the panelists

Ryan Calo is the Lane Powell and D. Wayne Gittinger Professor at the University of Washington School of Law. Calo’s research on law and emerging technology appears in leading law reviews and technical publications and is frequently referenced by the national media. His work has been translated into at least four languages. He has testified three times before the United States Senate and has been a speaker at President Obama’s Frontiers Conference, the Aspen Ideas Festival, and NPR’s Weekend in Washington. Calo co-directs the University of Washington Tech Policy Lab.

Cindy Cohn is the Executive Director of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. From 2000-2015 she served as EFF’s Legal Director as well as its General Counsel. Cohn first became involved with EFF in 1993, when EFF asked her to serve as the outside lead attorney in Bernstein v. Dept. of Justice, the successful First Amendment challenge to the U.S. export restrictions on cryptography. She has been named to TheNonProfitTimes 2020 Power & Influence TOP 50 list, honoring 2020’s movers and shakers. In 2018, Forbes included Cohn as one of America’s Top 50 Women in Tech. The National Law Journal named Cohn one of the 100 most influential lawyers in America in 2013, noting: “[I]f Big Brother is watching, he better look out for Cindy Cohn.” She was also named in 2006 for “rushing to the barricades wherever freedom and civil liberties are at stake online.” In 2007 the National Law Journal named her one of the 50 most influential women lawyers in America. In 2010 the Intellectual Property Section of the State Bar of California awarded her its Intellectual Property Vanguard Award and in 2012 the Northern California Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists awarded her the James Madison Freedom of Information Award.

Jacob Hoffman-Andrews leads EFF’s work on the Let’s Encrypt project, which assists over 400 million domain names in providing HTTPS encryption to their visitors. His areas of interest also include AI, online authentication (in particular multifactor authentication and passkeys), trusted execution environments and attestations, browser security, DNS, and memory safety. Besides Let’s Encrypt’s Boulder software, he is a maintainer of the go-jose package, rustls-ffi, rustdoc, and ureq. Prior to EFF, Hoffman-Andrews worked on security at Twitter and mapping at Google.

Tadayoshi Kohno is a professor in the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington. He is also the Associate Dean for Faculty Success in the University of Washington College of Engineering. His research focuses on helping protect the security, privacy, and safety of users of current and future generation technologies. Kohno has authored more than a dozen award papers, has presented his research to the U.S. House of Representatives, had his research profiled in the NOVA ScienceNOW “Can Science Stop Crime?” documentary and the NOVA “CyberWar Threat” documentary, and is a past chair of the USENIX Security Symposium. Kohno is the co-author of the book Cryptography Engineering, co-editor of the anthology Telling Stories, and author of the novella Our Reality. Kohno co-directs the University of Washington Computer Security & Privacy Research Lab and the Tech Policy Lab.

Franziska Roesner is the Brett Helsel Associate Professor of computer science and engineering at the University of Washington where she studies and teaches computer security and privacy. She works on emerging technologies, end-user needs, online mis/disinformation, and more. In 2017, MIT Technology Review named Roesner as one of the 35 “Innovators Under 35” for her work on privacy and security in emerging technologies. Roesner’s research has uncovered privacy risks in technologies, such as user tracking by third parties on websites and data collection by toys connected to the internet. Roesner co-directs the University of Washington Computer Security & Privacy Research Lab and is a faculty associate at the Tech Policy Lab.

About the hosts

Electronic Frontier Foundation | Since 1990, the Electronic Frontier Foundation has fought for your rights to privacy and free speech online. Their mission is to ensure that technology supports freedom, justice, and innovation for all people of the world. EFF is a member-supported nonprofit! Get involved and support their work at eff.org/donate.

Society + Technology at UW | Society + Technology at UW is a new program that uplifts the social, societal, and justice aspects of technologies through programming that supports research, teaching, and learning across the three UW campuses and the School of Medicine. Hosted by the Tech Policy Lab, Society + Technology also supports the Science, Technology, Society Studies (STSS) graduate certificate program.

UW Tech Policy Lab | The Tech Policy Lab is a unique, interdisciplinary collaboration at the University of Washington that aims to enhance technology policy through research, education, and thought leadership. Founded in 2013 by faculty from the University’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering, Information School, and School of Law, the Lab aims to bridge the gap between technologists and policymakers and to help generate wiser, more inclusive tech policy.

This event was possible thanks to the support of all three partners, with special thanks to Melissa Srago, Alex Bolton, Monika Sengul-Jones, Sarah Wang, Nick Logler, Beatrice Panattoni, Vannary Sou, Sean Lim, Miki Kusunose, and Nathan Lee, volunteers and student interns from the University of Washington. Thanks to Felix Aguilar on AV tech, and our partners at CoMotion, including Prince I. Ovbiebo, Caroline Hansen, and Donna R. O’Neill.