Part I of the New World Order was concerned with the chasm between the policies that rich countries prescribe to others vs. themselves to weather the great recession.

Part II in this saga is a sad example from the European Commission. It has gotten into the IMF's business of handing out short term loans to countries with balance of payment crises, specifically "Non-Euro Currency EU Countries." The Memorandum of Understanding is another testimony prescribe bitter medicine that they themselves are smart enough not to drink: specifically

"The disbursement of each further installment shall be made on the basis of a satisfactory implementation of the economic programme of the Romanian Government. Specific economic policy criteria for each disbursement are specified in Annex 1. The overall objectives of the programme are the following : a. Fiscal consolidation is a cornerstone of the adjustment programme… a gradual reduction of the fiscal deficit is envisaged, from 5.4% of GDP in 2008 to 5.1% of GDP in 2009, 4.1% of GDP in 2010 and below 3% of GDP in 2011 [emphasis added]. The adjustment will be mainly expenditure-driven, by reducing the public sector wage bill, cutting expenditure on goods and services…"

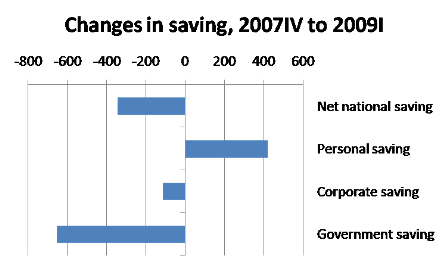

Ok, and now lets look what other major countries have done to weather the crisis. To quote Christina Romer (Head of the US Council of Economic Advisors) "Virtually every major country has enacted fiscal expansions during the current crisis. They have done so … because it works." Here are the numbers: