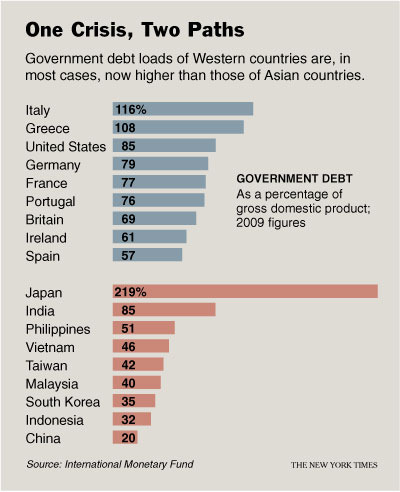

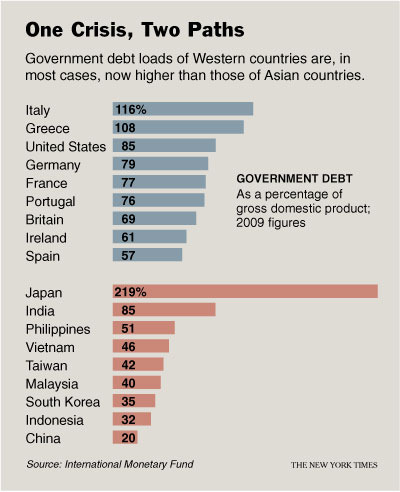

It is impressive that creditors worry about Greece but Japan's debt to GDP is TWICE as large. In addition, Japan's growth in past 20 years has been anemic, while income in Greece just about doubled…

Here is some additional information from Credit Suisse. Their research department crunches the numbers and finds that while private savings might be able to cover the fiscal deficit in the short run, in the long run their simulations suggest:

a 50% cut in public pensions and healthcare is necessary in the next 45 years, along with a 15% sales tax increase, or a massive public debt monetization (underwriting of government bonds by the Central Bank of Japan) would be needed.The Bank of Japan would be required to buy almost all of the outstanding public debt (180% of GDP) today to achieve fiscal sustainability. Scary Stuff.

Then Again, You Can’t Put Lipstick on THESE PIGS:

(careful, this is not an apples-to-apples comparison. Below are annual deficits for prominent US states (budget gaps as % of total budgets) while the above numbers referred to the total accumulated debt for countries.)

California:

22%, or

$22.2 billion

Florida: 19.9%, or $5.1 billion

Arizona: 19.9%, or $2 billion

Nevada: 16%, or $1.2 billion

New York: 9.8%, or $5.5 billion

New Jersey: 7.7%, or $2.5 billion

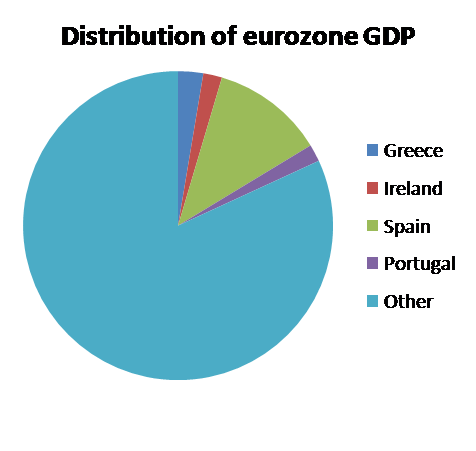

All data for fiscal year 2008, Source Businessweek. Barry Rieholtz points out that 43 (!) states in the US are in some form of financial distress. All by itself, the insolvent nation-state of California is the 8th largest economy in the world (it is the size of France…) According to the CIA Factbook, Greece is number 34. That is a lot of hyperventilating about a relatively small impact to global GDP. Italy is 11, Spain is 13, Portugal is 50, and Ireland is 56.

Here is the Wall Street Journal's take on the issue (from the The Wall Street Journal Economics: Macro Weekly Review)

by: Yuka Hayashi, Mar 01, 2010

SUMMARY: Bond traders have been relatively sanguine about Tokyo's massive pile of debt, but that attitude could be tested over the next three months.

QUESTIONS:

1. Why is it important to measure debt relative to GDP?

2. What are the potential adverse consequences that Japan will face if its debt continues to increase in size?

3. What fiscal policy measures is Japan considering to reduce the size of its debt?

4. What difference will it make if Japan decides to increase taxes gradually rather than all at once?

5. What difference does it make that most of Japan's debt is held by domestic rather than foreign investors?

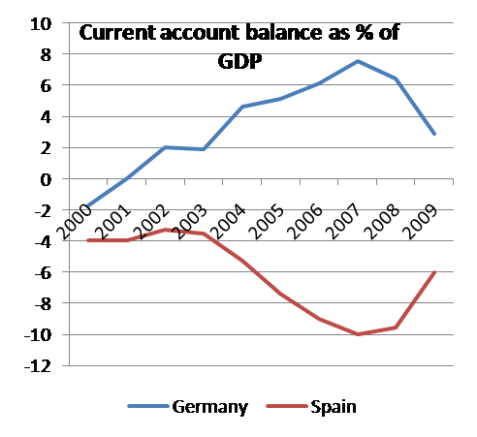

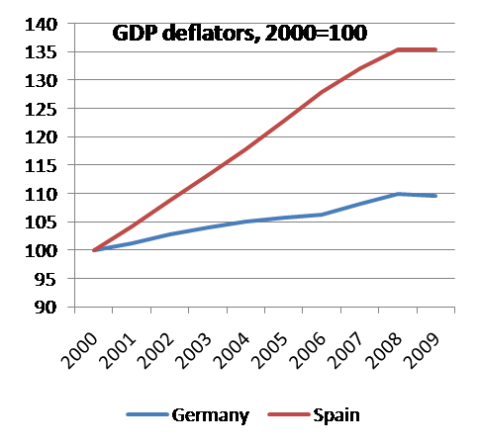

![[SPAIN_p1]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/P1-AT968_SPAIN__NS_20100224184413.gif)