The euro has been depreciating against the dollar over the past few weeks. The implications of this development for the US depend critically on (1) the extent of the depreciation, (2) the duration, and (3) the source of the depreciation. (See Jim's post for other links.)

Figure 1: EUR/USD exchange rate, monthly averages (blue line), and value as of 5/14; and trade weighted value of USD against broad basket of currencies (red line), and value as of 5/14. NBER defined recessions shaded gray. Source: Federal Reserve Board via FRED II, NBER.

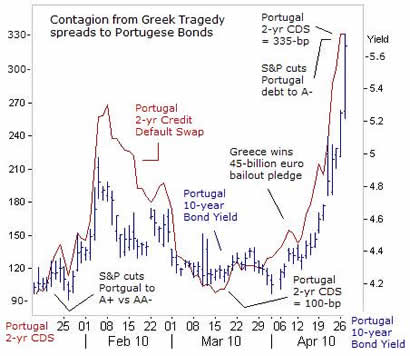

The euro has depreciated since the 2009M11 average, by about 10.5% in log terms, and about 16.1% versus 2008M07, just before the Lehman bankruptcy. What the graph makes clear is that the first flight-to-safety induced dollar appreciation faded after about a year. This second dollar appreciation might be construed as another flight-to-safety. How lasting will this appreciation be? Much depends upon how and whether the euro area governments resolve the current crisis. It also depends upon the desirability of US dollar denominated assets, including Federal government debt.

Since I am less pessimistic than some others regarding the short to medium term deficit outlook for the US [0], I think that the upward appreciation of the dollar against the euro might be fairly persistent. That being said, Figure 1 also highlights the fact that euro movements do not translate one-for-one into dollar value movements. At the monthly to annual frequency, the elasticity is about 0.4 to 0.45 (calculated as log-changes on log-changes).

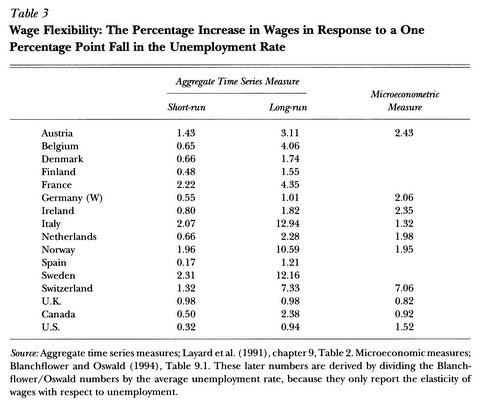

It's difficult to evaluate the impact of exchange rate depreciation on GDP, and other variables, without taking a stand on what causes the exchange rate movements. The OECD has recently released documentation on their new macroeconometric model. One of the experiments implemented involves a 10% euro depreciation against a basket of currencies. From Karine Hervé, Nigel Pain, Pete Richardson, Franck Sédillot and Pierre-Olivier Beffy, The OECD's New Global Model, Economics Department Working Papers No. 768 (May 2010) (h/t Torsten Slok):

The simulations are conducted in the following fashion:

The exchange rate simulations assume sustained 10% nominal effective depreciations, individually for US dollar, yen and euro rates, against all other currencies, assuming that monetary policy follows a standard Taylor rule and that fiscal policy is set by endogenous rule. Following depreciation in the first quarter, the exchange rate is assumed to remain at the new level throughout the simulation period with the sustained shift assumed to be exogenous, coming from unexplained movements in markets expectations, rather than being policy induced or reflecting an identifiable change in economic fundamentals. The possible endogenous influence of simulated changes in interest rates on exchange rates, which might tend to offset the original shock, is therefore not taken into account. For this reason, these shocks are not particularly realistic, but serve rather to illustrate the role and transmission channels of exchange rates in the model.

The key channel is expenditure switching; a depreciation induces more spending on euro area goods, and less on those of the RoW. However, the table indicates the effect of a 10% euro depreciation would only have a modest impact on US GDP — a 0.2 percentage point deviation relative to baseline two years out, if sustained. The historical correlation between the euro/dollar rate and the BIS trade weighted value of the euro is about 0.5 (that is, the elasticity is about 0.5), so the euro depreciation since the April average is only about 5%, and hence the negative impact about half that indicated in the table.

There are other channels incorporated in the model, including valuation effects from exchange rate changes (see this post for discussion).

Part of the reason that the effect on the US is modest is that changes in the euro/dollar exchange rate are not the same as changes in the USD value. This is illustrated in Figure 1. The short run elasticity of (broad) trade weighted exchange rate with respect to the euro/dollar exchange rate is about 0.4-0.45 (at the one month to one year horizon).

The model is fairly conventional in terms of macroeconomics — in the short run output is largely demand determined, while in the long run it is supply determined (in other words, pretty much like in most standard macro textbooks). The key distinction is econometric; the key macro relationships are estimated using error correction models.

One channel that is not included (and would not be included in a open economy RBC [1] or a standardDSGE) is the effect coming from cross-border propagation of equity price declines. For that, one might need to appeal to financial stress indicators, as discussed in this post.

Interesting side point: the government spending multipliers are substantially greater than unity.

![[ABREAST]](http://sg.wsj.net/public/resources/images/MI-BD080_ABREAS_NS_20100502191214.gif)