Including Central Bank Reserves can be found at the Center for Financial Stability.

Deficits, Elections & The IMF

Why have Hungary and the IMF been chatting in the first place? A previous post highlights Hungary's fiscal deficit problem, which led to increased country risk and foreign reluctance to finance the Hungarian external deficit. As Chapter 15 and this post by Simon Johnson outline, this is a classic case for the IMF — especially if elections are coming up. Here is the story from the Financial Times:

IMF breaks off talks with Hungary

This is a story we used to see a lot more ten or twenty years ago. Hungary and IMF have broken off talks, as the new Hungarian government refuses to accept further austerity measures. The FT reports that the message is not entirely clear, as the economy minister later accepted that Hungary would cut its budget deficit to 3% of GDP by 2011. It looks as though the government is mindful of the local elections, which could see the rise of a far-right party that opposes foreign capital. The election are held in October. The EU also criticised the Hungarian policies, as well as attempt to undermine the independence of the central bank. Hungary currently does not need to draw on the €20bn standby facility, but the article says the country’s financial position remains precarious. The forint fell by over 3% against the euro after the news of the breakdown of talks came out.

Update 7/23/2010: When It Rains, It Pours

From Bloomberg: Hungary Credit Rating May Be Cut to Junk After IMF Talks Fail

Standard & Poor’s said it is reviewing Hungary’s credit rating for possible downgrade after the collapse of negotiations with the International Monetary Fund and European Union. A cut would give Hungary’s debt a junk rating.

From Reuters: Ratings agencies threaten Hungary with downgrade

Moody's placed Hungary's Baa1 local and foreign currency government bond ratings on review, citing increased fiscal risks after the International Monetary Fund and the European Union suspended talks over their 20 billion euro ($25 billion) financing deal at the weekend.

Hans Rosling believes that making information more visually accessible has the potential to change the quality of the information itself. His website Gapminder allows data to be displayed to experience development in motion. He also has a great TED talk. Here is one of his pictures:

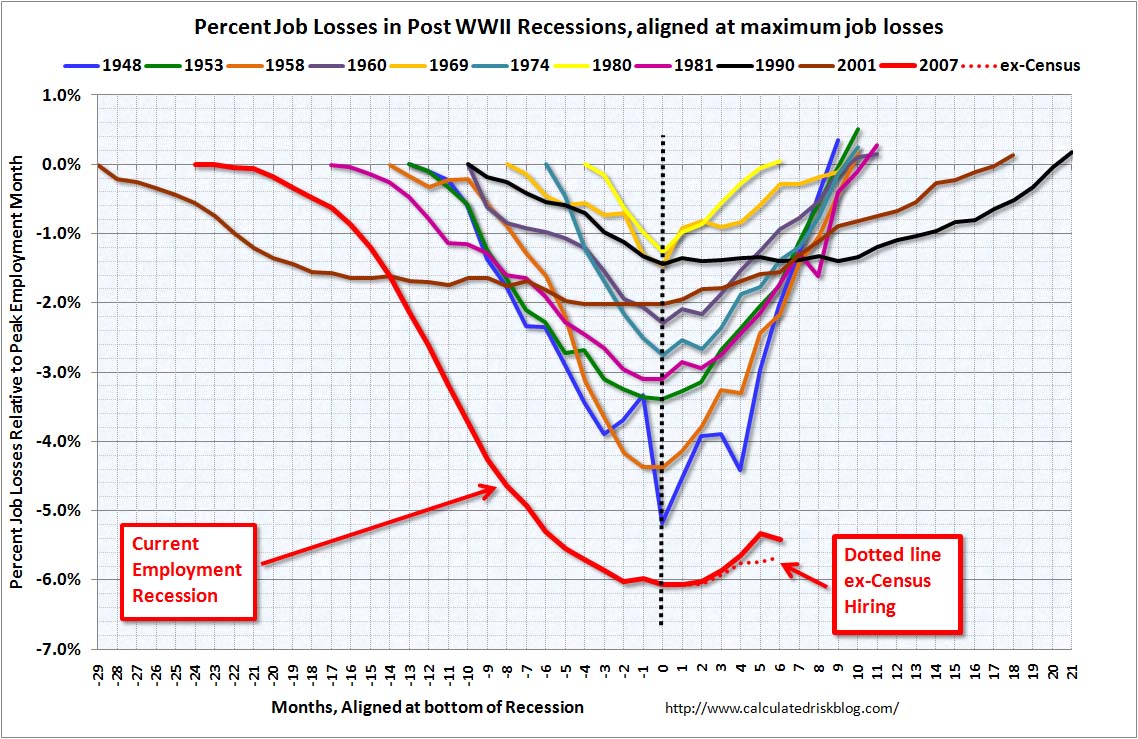

Output has recovered in the US

but employment is still absolutely dismal

And there is little evidence for an imminent hiring spree.

According to the Mundell-Fleming model, a small, open economy cannot achieve all three of these policy goals at the same time:

1. A fixed exchange rate

2. An open capital market (no capital controls)

3. An independent monetary policy

in pursuing any two of these goals, a nation must forgo the third. Every course on international finance should conclude with an exercise to prove the International Finance Trilemma. GregMankiw provides the popular review of the "impossible trinity." BradDeLong provides the following concrete examples

Countries on the gold standard (like the U.S. from 1873-1914) chose to have a fixed exchange rate and open capital markets. They did not have independent monetary policy. (The U.S. did not even have a central bank, although the Treasury performed some of a central bank's functions.)

The U.S. today chooses to have an open capital market and an independent monetary policy. Thus it does not have a fixed exchange rate: you cannot take your dollars to the San Francisco Fed and exchange them for gold or foreign currency at a set price.

Countries in the Euro area, like countries on the Gold Standard, have chosen to have open capital markets and fixed exchange rates and thus they do not have independent monetary policies. The European Central Bank (the ECB) sets monetary policy for all countries in the Euro-zone.

China has (roughly) chosen to have a fixed exchange rate and an independent monetary policy. This means that they must have capital controls, which they indeed do. For example, Article 9 of The People's Bank of China Decree [2006], No. 3 states 1: An individual's foreign exchange sales and domestic individual's foreign exchange purchases shall be imposed an annual limit. Within the annual limit, an individual can conduct a sale or purchase business with a bank by presenting valid identity documents; beyond the annual limit, an individual can conduct a current account business with a commercial bank by presenting valid.

The Burda and Wyplosz textbook also provides a nice illustration. What happens if a nation tries to pursue all three goals at once? To start with they posit a nation with a fixed exchange rate at equilibrium with respect to capital flows as its monetary policy is aligned with the international market. However the nation then adopts an expansionary monetary policy to try to stimulate its domestic economy. This involves an increase of the monetary supply, and a fall of the domestically available interest rate. Because the internationally available interest rate adjusted for forex differences has not changed, market participants are able to make a profit by borrowing in the countries currency and then lending abroad – a form of Carry trade. With no capital control market players will do this en masse. The trade will involve selling the borrowed currency on the forex market in order to acquire foreign currency to lend abroad – this tends to cause the price of the nation's currency to drop due to the sudden extra supply. Because the nation has a fixed exchange rate, it must defend its currency and will sell its reserves to buy its currency back. But unless the monetary policy is changed back, the international markets will invariably continue until the governments foreign exchange reserves are exhausted, causing the currency to devalue, thus breaking one of the three goals and also enriching market players at the expense of the government that tried to break the impossible trinity.

New evidence that economists had the entire stimulus vs. no stimulus debate 80 years ago. Damning evidence against economics as a science. What is the definition of progress/consensus if 80 years of theories and data do not produce insights into such fundamental events as great depressions/recessions. This tête-à-tête between Keynes et al. and Hayek et al. can actually be judged with the beautiful hindsight of history. On one side in the ring areJohn Cochrane and Luigi Zingales. On the other side are Paul Krugman and Brad DeLong. Here is Chochrane:

Nobody is Keynesian now, really… Now, we all understand that growth, fuelled by higher productivity, is the key to prosperity… We now understand the links between money and inflation, and the natural rate of unemployment below which inflation will rise… We all now understand the inescapable need for markets and price signals, and the sclerosis induced by high marginal tax rates, especially on investment…

Most of all, modern economics gives very little reason to believe that fiscal stimulus will do much to raise output or lower unemployment. How can borrowing money from A and giving it to B do anything? Every dollar that B spends is a dollar that A does not spend. The basic Keynesian analysis of this question is simply wrong. Professional economists abandoned it 30 years ago…

There is little empirical evidence to suggest that stimulus will work either. Empirical work without a plausible mechanism is always suspect, and work here suffers desperately from the correlation problem… We do know three things. First, countries that borrow a lot and spend a lot do not grow quickly. Second, we have had credit crunches periodically for centuries, and most have passed quickly without stimulus. Whether the long duration of the great depression was caused or helped by stimulus is still hotly debated. Third, many crises have been precipitated by too much government borrowing.

Neither fiscal stimulus nor conventional monetary policy (exchanging government debt for more cash) diagnoses or addresses the central problem: frozen credit markets. Policy needs first of all to focus on the credit crunch. Rebuilding credit markets does not lend itself to quick fixes that sound sexy in a short op-ed or a speech, but that is the problem, so that is what we should focus on fixing.

The government can also help by not causing more harm. The credit markets are partly paralysed by the fear of what great plan will come next. Why buy bank stock knowing that the next rescue plan will surely wipe you out, and all the legal rights that defend the value of your investment could easily be trampled on? And the government needs to keep its fiscal powder dry. When the crisis passes, our governments will have to try to soak up vast quantities of debt without causing inflation. The more debt there is, the harder that will be.

And in the other side of the ring is Paul Krugman, who can hardly contain himself after reading the Keynes/Hayek debate from 1932:

First, Hayek was as bad on the Depression as I thought. The claim that “many of the troubles of the world at the present time are due to imprudent borrowing and spending on the part of the public authorities” — in 1932! — is bizarre. The claim that barriers to trade and capital movement were what was preventing recovery is as crazy as … as .. claiming that we’re in a slump because workers decided to take a break in the face of prospective Obama tax hikes.

Second, Keynes pretty much had the policy implications of the General Theory down long before he actually worked out the detailed analysis. I’m especially struck by the way he grasped, right from the start, the point that if higher private spending expands employment in a slump, so does higher public spending.

Third, it’s deeply tragic that we’re having to have this debate all over again, as the world economy slides into deflation and stagnation.

It may be time to buy Gold. While the precious metal is at all time highs, some highly intelligent commentators see us staring at the abyss:

Willem Buiter, a highly distinguished economists (now chief economist at Citi) believes Europe need not Euro 1 trillion, but Euro 2 trillion in tarp money. Here is his line of reasoning. I thought it was fitting when I heard the Euro 1 trillion package referred to as "Wundertuete" or "Grab Bag" since no one has any idea if/when/how or how much a country in need could procure from that fund. Paul Krugman thinks Obama's TARP 1 was too small a similar line of reasoning has been proposed byBrad DeLong. If all that money is indeed needed at some point to pull the economy out of the ditch, government debt is going to skyrocket. If these commentators are correct, we're between a rock and a hard place: debt or depression.

On the lighter side, the alternative is to listen to Ed Prescott (also a very intelligent economist, in fact, a Nobel Laureate). He proposes the view (called Real Business Cycles) that business cycles and indeed great recessions or depressions can be modeled as technological retrogression (people forget technology). Sounds strange, I know, but that's just the beginning (via Stephen Williamson):

"Ed Prescott did pathbreaking work in the economics profession, and his Nobel prize is well-deserved. However, I doubt that there were any people in the room yesterday who took Ed seriously. Ed's key points were: 1. Monetary policy does not matter. 2. Financial factors are the symptoms, not the causes, of the recent downturn. 3. The recession was due to an Obama shock, i.e. labor supply fell because US workers anticipate higher future taxes."

Chapter 15 outlines Expenditure Switching and Expenditure Reducing Policies. None one could have described the heart ache better than former IMF chief economist Simon Johnson. After using either the IS/LM or the TB/Y model to indicate how a country can end up with a balance of payments crisis, it may be interesting to read Johnson's account of the IMF's image problem. He highlights that no matter how different countries are the sources of the problems are almost always similar (as the models in Chapter 15 confirm…). His descriptive also highlights why the political powerless almost are always the losers when in the harsh austerity measures kick in, and that this hardly makes the IMF radar :

"ONE THING YOU learn rather quickly when working at the International Monetary Fund is that no one is ever very happy to see you. Typically, your “clients” come in only after private capital has abandoned them, after regional trading-bloc partners have been unable to throw a strong enough lifeline, after last-ditch attempts to borrow from powerful friends like China or the European Union have fallen through. You’re never at the top of anyone’s dance card.

The reason, of course, is that the IMF specializes in telling its clients what they don’t want to hear. I should know; I pressed painful changes on many foreign officials during my time there as chief economist in 2007 and 2008. And I felt the effects of IMF pressure, at least indirectly, when I worked with governments in Eastern Europe as they struggled after 1989, and with the private sector in Asia and Latin America during the crises of the late 1990s and early 2000s. Over that time, from every vantage point, I saw firsthand the steady flow of officials—from Ukraine, Russia, Thailand, Indonesia, South Korea, and elsewhere—trudging to the fund when circumstances were dire and all else had failed.

Every crisis is different, of course. Ukraine faced hyperinflation in 1994; Russia desperately needed help when its short-term-debt rollover scheme exploded in the summer of 1998; the Indonesian rupiah plunged in 1997, nearly leveling the corporate economy; that same year, South Korea’s 30-year economic miracle ground to a halt when foreign banks suddenly refused to extend new credit.

But I must tell you, to IMF officials, all of these crises looked depressingly similar. Each country, of course, needed a loan, but more than that, each needed to make big changes so that the loan could really work. Almost always, countries in crisis need to learn to live within their means after a period of excess—exports must be increased, and imports cut—and the goal is to do this without the most horrible of recessions. Naturally, the fund’s economists spend time figuring out the policies—budget, money supply, and the like—that make sense in this context. Yet the economic solution is seldom very hard to work out.

No, the real concern of the fund’s senior staff, and the biggest obstacle to recovery, is almost invariably the politics of countries in crisis.

Typically, these countries are in a desperate economic situation for one simple reason—the powerful elites within them overreached in good times and took too many risks. Emerging-market governments and their private-sector allies commonly form a tight-knit—and, most of the time, genteel—oligarchy, running the country rather like a profit-seeking company in which they are the controlling shareholders. When a country like Indonesia or South Korea or Russia grows, so do the ambitions of its captains of industry. As masters of their mini-universe, these people make some investments that clearly benefit the broader economy, but they also start making bigger and riskier bets. They reckon—correctly, in most cases—that their political connections will allow them to push onto the government any substantial problems that arise…"

Here is the notion of Optimal Currency Areas in two pictures

The eurozone pain is mainly in Spain, by Stephen Gordon:

…I charted the employment losses for the G7 countries and noted that while the US was still bouncing along the trough of of a deep recession, the other countries were less badly-hit. But there was an important country missing from that graph – and it wouldn't have been included in a chart for the G20, either.

It turns out that even though only 14% of the people who use the euro live in Spain, the fall in Spanish employment accounts for 41.5% of the total eurozone losses since the peak in 2008Q3:

Here's a similar graph for the United States. I couldn't be bothered to do it for all 50 states, so I divided it up according to the 12 Federal Reserve districts. The data are not seasonally adjusted, so the employment losses are those between November 2007 and November 2009.

I must say that I was surprised by how close these data points were to the 45o degree line. Most of the districts saw employment losses that were roughly proportional to their population. The most notable exceptions are the Dallas FRD (which did relatively well) and the Chicago and Atlanta FRDs, which were hardest hit by the collapse of manufacturing and the housing market, respectively.

Much of the difference between these two graphs must be attributed to the fact that the United States has a federal government that can transfer tax revenues generated in Texas to finance spending in California. If the euro had been designed properly, German tax revenues would now be propping up Spanish aggregate demand. Instead, Germany is embarking on a program of austerity.

Spanish policy makers must be really, really sorry they adopted the euro.

The Theory on "Optimal Currency Areas" is at least 50 years old. But somehow the principle insight of this theory did not make it into the collective thinking of key economists and policy makers in Europe. They believe that a currency union like the Eurozone can exist without fiscal transfer mechanisms or sufficient labor mobility.

An optimum currency area is a geographical region in which it would maximize economic efficiency to have the entire region share a single currency. It describes the optimal characteristics for the merger of currencies or the creation of a common currency. The creation of the euro is often cited as the most recent largest-scale case study of the engineering of an optimum currency area. In theory. The theory of the optimal currency area was pioneered by economist Robert Mundell ("A Theory of Optimum Currency Areas", American Economic Review 51 (1961): 657-665). Credit often goes to Mundell as the originator of the idea, but others point to earlier work done in the area by Abba Lerner.

The four often cited criteria for a successful currency union are[5]: