When and how will the Fed and other central banks wind down

their mammoth asset purchases, also known as quantitative easing (QE)? Since the

start of the financial crisis, the Fed, the European Central Bank, the Bank of

England, and the Bank of Japan have used QE to inject more than $4 trillion of

additional liquidity into their economies. When these programs end, governments,

some emerging markets, and some corporations could be vulnerable. They need to

prepare.

- Research by the McKinsey Global Institute suggests that

lower interest rates saved the US

and European governments nearly $1.6 trillion from 2007 to 2012. This windfall

allowed higher government spending and less austerity. If interest rates were

to return to 2007 levels, interest payments on government debt could rise by 20%,

other things being equal. Governments in the US and the eurozone are

particularly vulnerable as interest rates

rise, governments will need to determine whether higher tax revenue or stricter

austerity measures will be required to offset the increase in debt-service

costs. - Likewise, QE saved firms $710

billion from lower debt-service payments, thus ultra-low interest rates boosted profits by about 5% in the US

and the UK,

and by 3% in the eurozone. This source of profit growth will disappear as

interest rates rise, and some firms will need to reconsider business models –

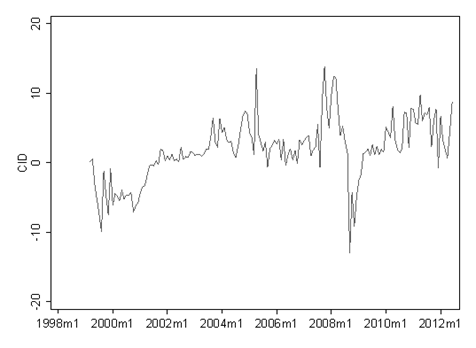

for example, private equity – that rely on cheap capital. - Emerging economies have also benefited from access to cheap

capital. Foreign investors’ purchases of emerging-market sovereign and

corporate bonds almost tripled from 2009 to 2012, reaching $264 billion. As QE programs end, emerging-market countries could see an outflow

of capital. - By contrast, households in the US

and Europe lost $630 billion in net interest

income as a result of QE. This hurt older households that have significant

interest-bearing assets, while benefiting younger households that are net

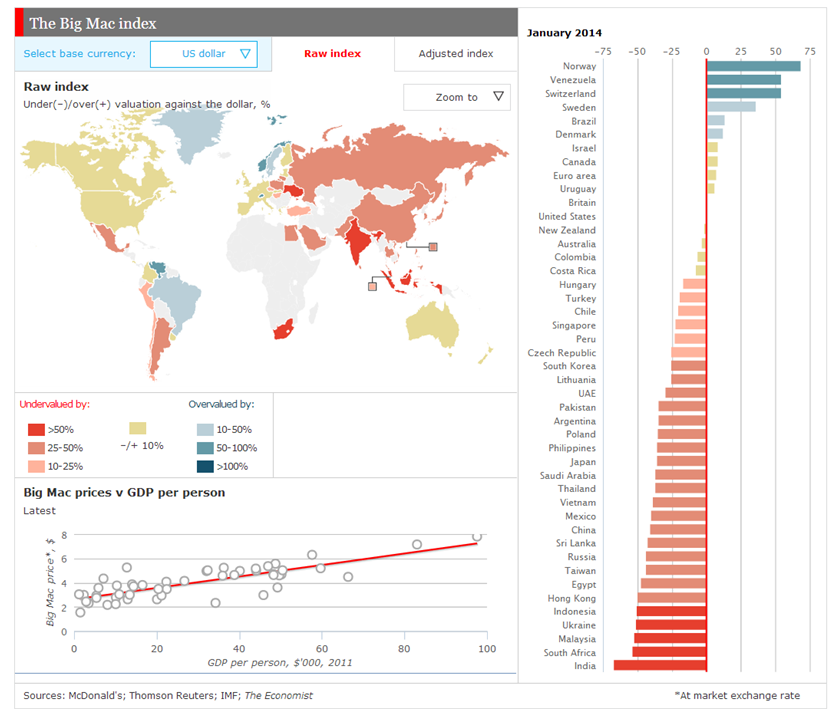

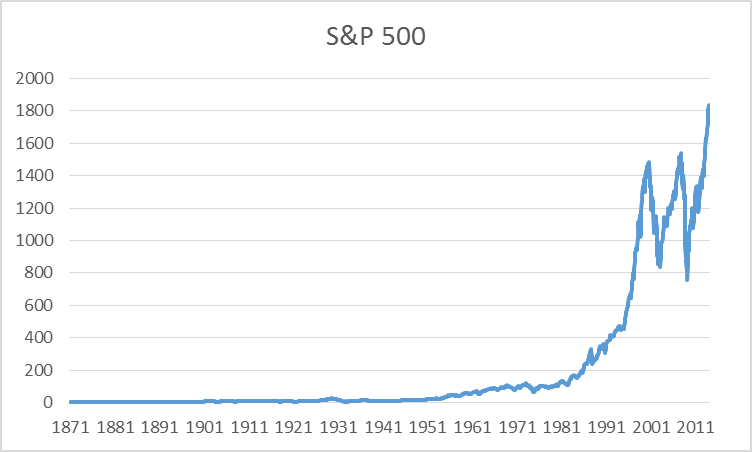

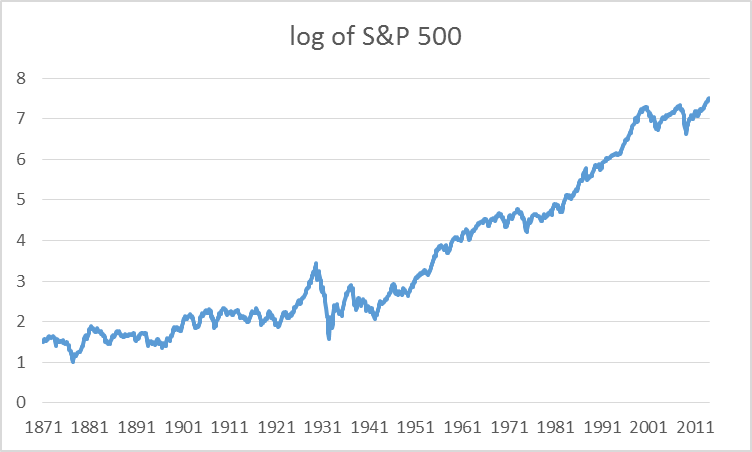

borrowers. - QE may have also generated NEW asset-price bubbles in

some sectors, especially real estate. The International

Monetary Fund noted in 2013 that there were already “signs of overheating in

real-estate markets” in Europe, Canada,

and some emerging-market economies.

Of course, QE and ultra-low interest rates served a purpose.

If central banks had not acted decisively to inject liquidity into their

economies, the world could have faced a much worse outcome. Economic activity

and business profits would have been lower, and government deficits would have

been higher. When monetary support is finally withdrawn, this will be an

indicator of the economic recovery’s ability to withstand higher interest rates.

Nevertheless, all players need to understand how the end of QE

will affect them. After more than five years, QE has arguably entrenched

expectations for continued low or even negative real interest rates – acting

more like addictive painkillers than powerful antibiotics, as one commentator

has put it. Governments, companies, investors, and individuals all need to

shake off complacency and take a more disciplined approach to borrowing and

lending to prepare for the end – or continuation – of QE.