President Trump is said to have imposed the additional $200 billion in tariffs on China (beyond the initial $50 billion) “because China cannot retaliate” — China only imports $130 billion in US goods. Not so fast, the trade balance is not TB = X – M, but we measure its value (in dollar) as

TB = P[US] * X – E*{P[China]*(1+tariff)}*M, so a devaluation of the Yuan, or an appreciation of the dollar (E decreases) implies that Chinese goods appear cheaper to US consumers (even if prices in the US and China remain constant). Sufficiently cheaper perhaps to offset a tariff…

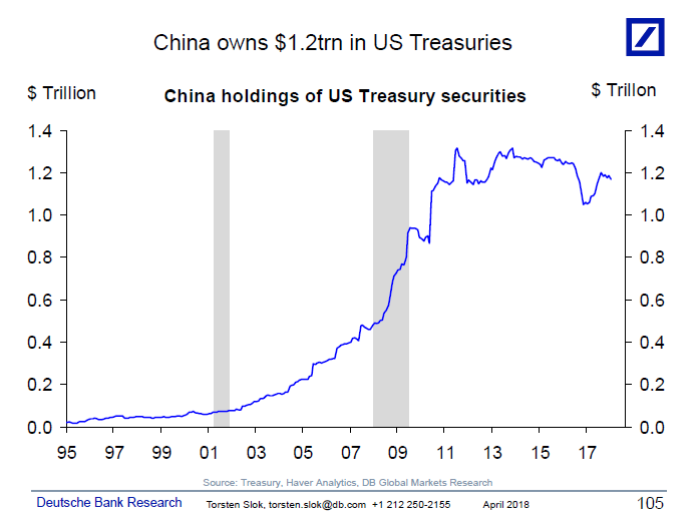

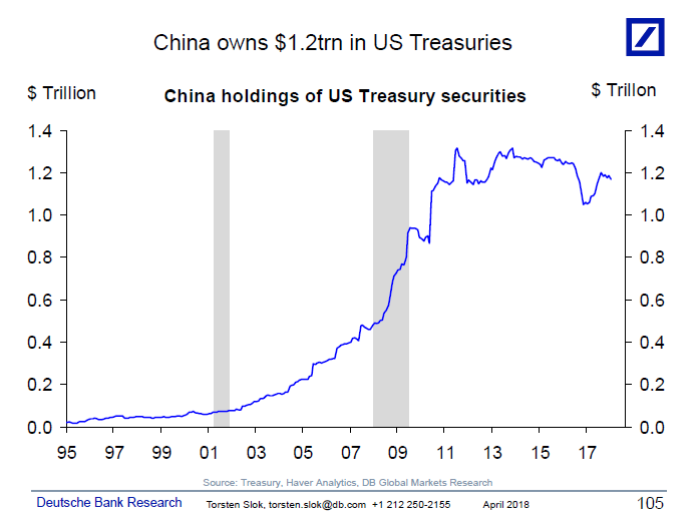

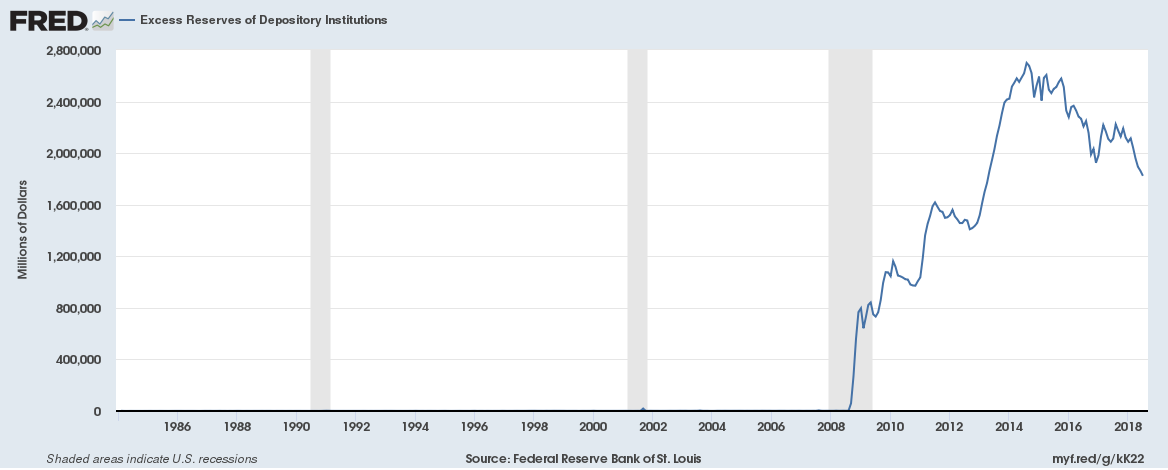

Menzie Chinn [you can skip the tariff analysis, if you have not taken econ 471] lays out nicely what that means for Exchange Rate Management: China has a managed exchange rate; so it could unload its Treasury Bills but the capital losses would be large. (Recent estimates of impacts on Treasury yields are here [this link is fyi only, not required).

Source: Torsten Slok, April Chartbook, DeutscheBank.

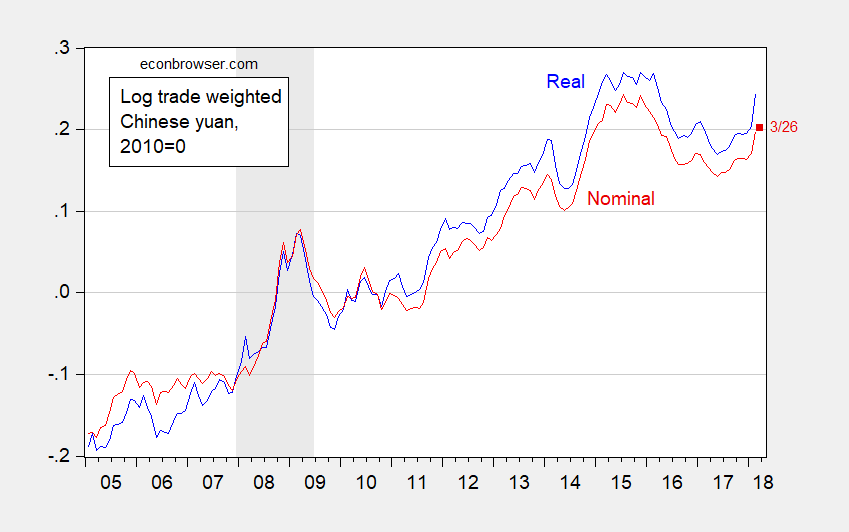

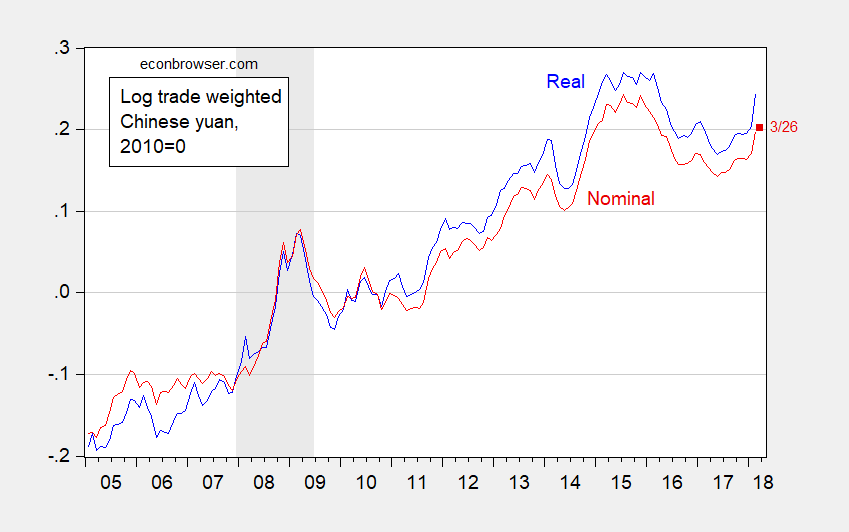

However, China could do the opposite, and buy more Treasury Bills, strengthening the dollar, i.e., weakening the yuan. There is substantial scope for depreciation, as shown in Figure 2. A 25% depreciation (log terms) would restore the CNY to 2011 levels. Figure 2: Log real trade weighted Yuan (blue), nominal (red), 2010=0. March 2018 observation for March 26. Source: BIS.

Figure 2: Log real trade weighted Yuan (blue), nominal (red), 2010=0. March 2018 observation for March 26. Source: BIS.

So, in order to restore competitiveness after Trump tariffs, all China needs to do is to engineer a depreciation/rebuild forex reserves. Of course a managed depreciation of the yuan would be declared “currency manipulation” by the Trump administration, who would then be calling the kettle black, since the white house first initiated the “trade manipulation” but imposing tariffs.

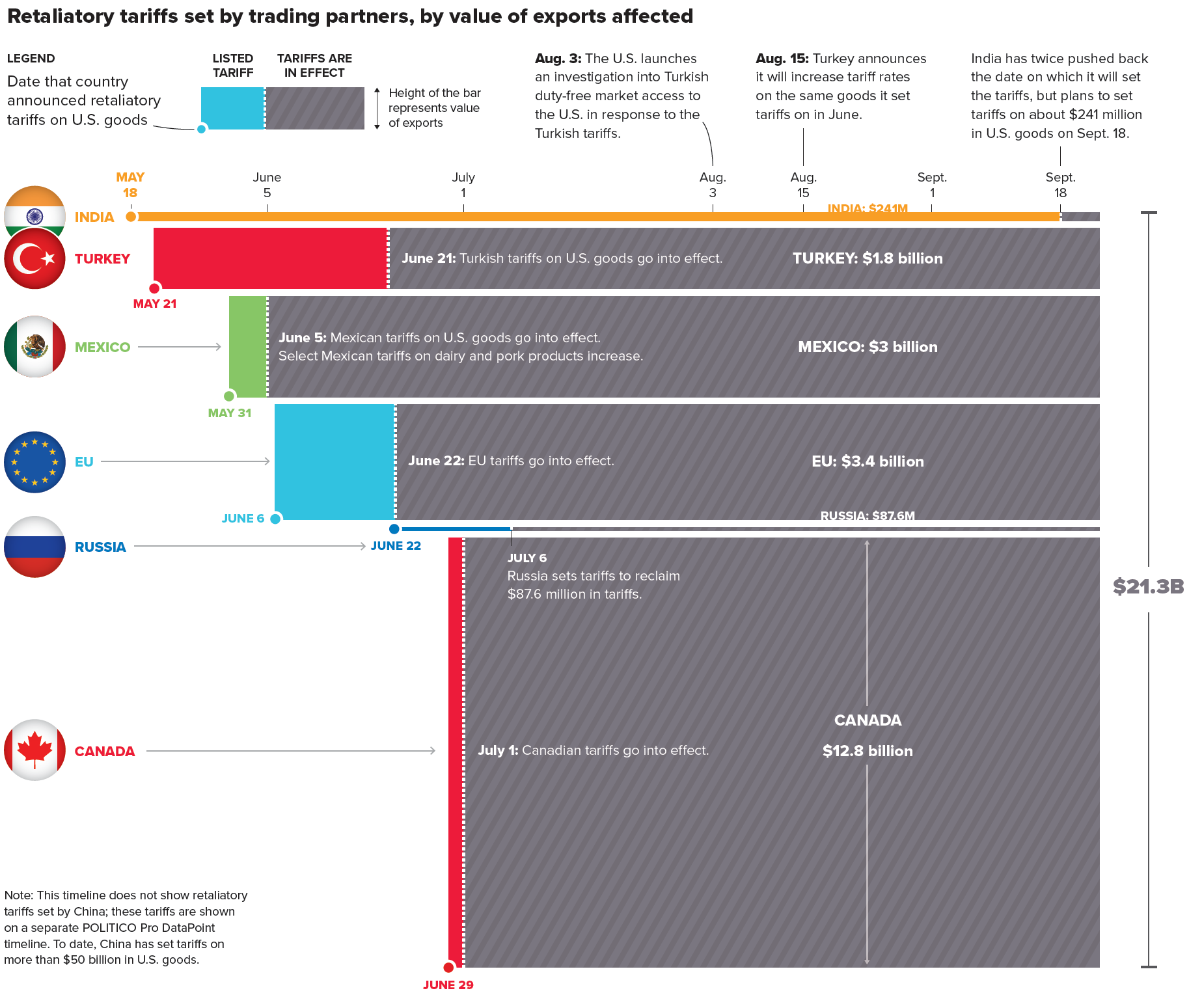

Update; 9/7/18 President Trump just announced he is ready to slap tariffs onto another $260 billion in Chinese goods (that’s $50bil + $200bil + $260bil = $510bil) which actually exceeds the current US trade deficit with China ($505billion). Perhaps the White House will come to its senses when it reads the Menzie Chinn post?

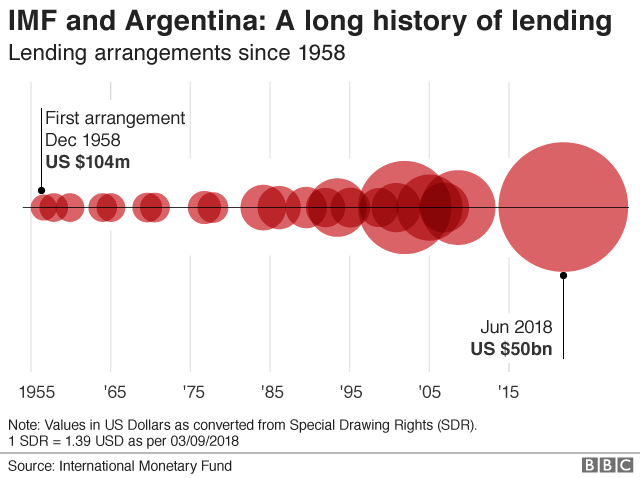

Source:

Source:

The Expenditure Reducing measures announced (exceeded the IMF requirements) include “taxes on exports of some grains and other products” and “about half of the nation’s government ministries will be abolished” and “half of ministry jobs being axed.” This after January’s cuts that froze government employees’ pay and cut “one out of every four ‘political positions’ appointed by ministers.”

The Expenditure Reducing measures announced (exceeded the IMF requirements) include “taxes on exports of some grains and other products” and “about half of the nation’s government ministries will be abolished” and “half of ministry jobs being axed.” This after January’s cuts that froze government employees’ pay and cut “one out of every four ‘political positions’ appointed by ministers.”