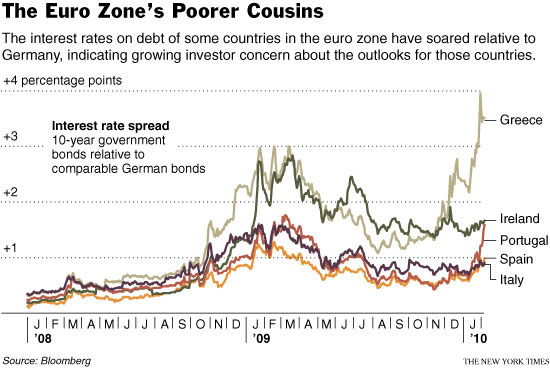

China is said to have started again started purchased US treasuries, the first time for the emerging country since September 2009. The Asian giant is once again the largest holder in US debt, passing Japan who took the title during China’s previous six-month sell off. Concerns about certain European debt situations in countries like Greece, Spain, and Portugal have caused a net return to purchasing the relative safety and security of good-old-fashion American debt, according to the Wall Street Journal. In a television interview with Bloomberg TV, the chief Asian strategist for Citigroup said, “The concern [with European debt]… is moving from how much it’s going to cost to the effect on growth.” He continued saying, “In Asia, there are clearly some headwinds.” Concerns of this debt have led the Euro to continue it’s dizzying fall today; The currency is now at a four-year low in comparison to the US dollar. Despite the amazingly large bailout from the Eurozone (nearly $1 trillion dollars), this decline has gone unimpeded for most of the last month.